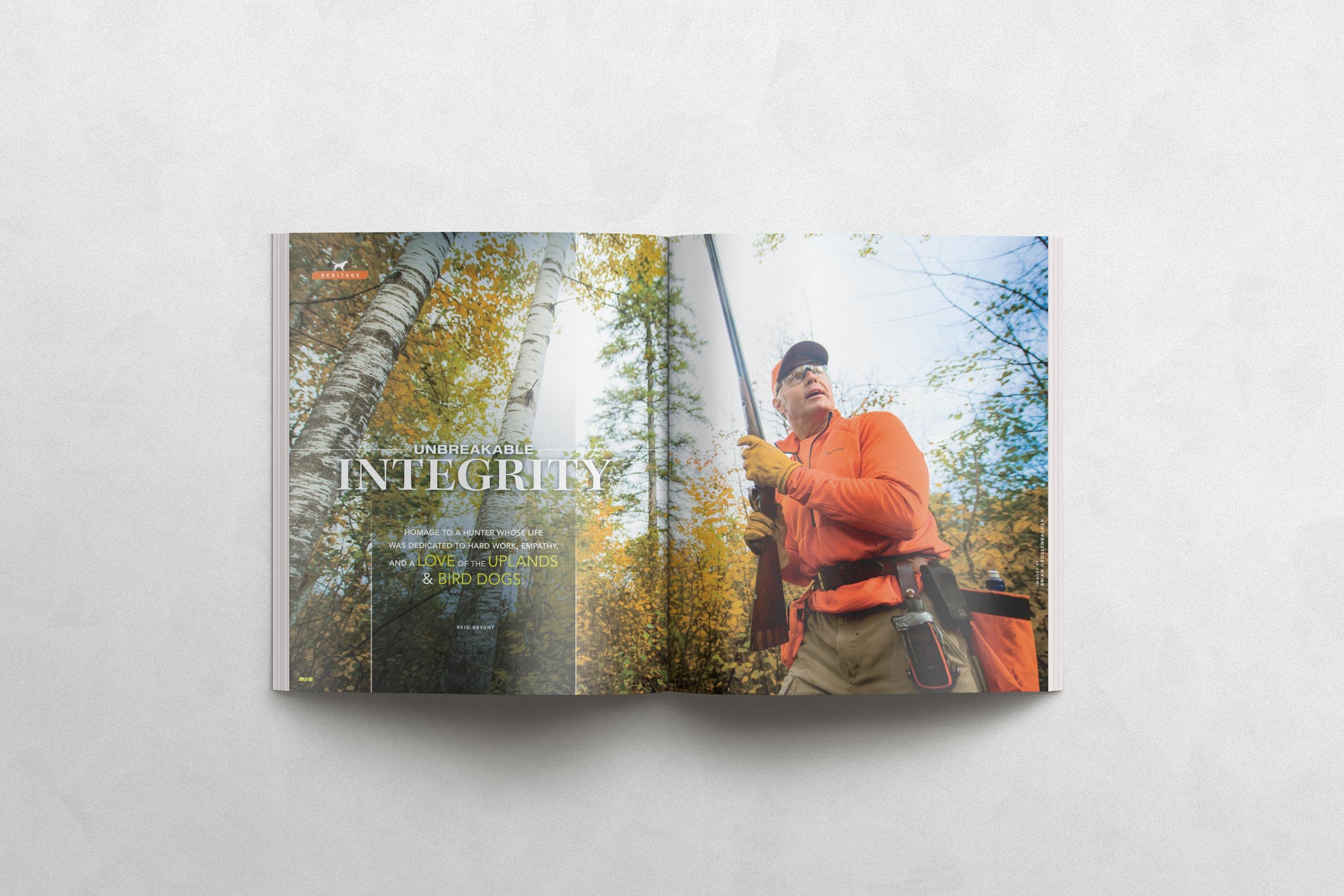

Unbreakable Integrity

Some time ago, an editor of the old guard told me to avoid the temptation of turning a simple hunting story into a eulogy. “Far more writers want to write about death than readers want to read about it…” he said in a thoughtful but firm refusal of my submission to his magazine. I found it somewhat ironic, this advice from a fellow whose days were spent tidying up accounts of critters escorted out of the living landscape at the hands of hunters and fishermen. Nonetheless, I heeded the editor’s advice, though the following may call that assertion into question. The story I am about to tell didn’t set out to be a eulogy… it set out to be a meditation on integrity, illustrated by a man whose compassion, conviction, and honesty were non-typical. That he passed away suddenly as I sat chewing on the lessons he taught me, perhaps was teaching me even as his cells mutinied, was a footnote that still makes me sad. But the story of his death, and the story of his life, are ones I am not quite ready to tell, even these years later. Those stories will indeed be a eulogy of sorts, and will require more space, perhaps more perspective on loss, than I have yet accumulated. So instead, this is the story of a man who thought hard about integrity, who loved his dogs, and whose life didn’t require an untimely death to make it emphatic. The emphasis was there all along, in the most lovely and uncomplicated ways.

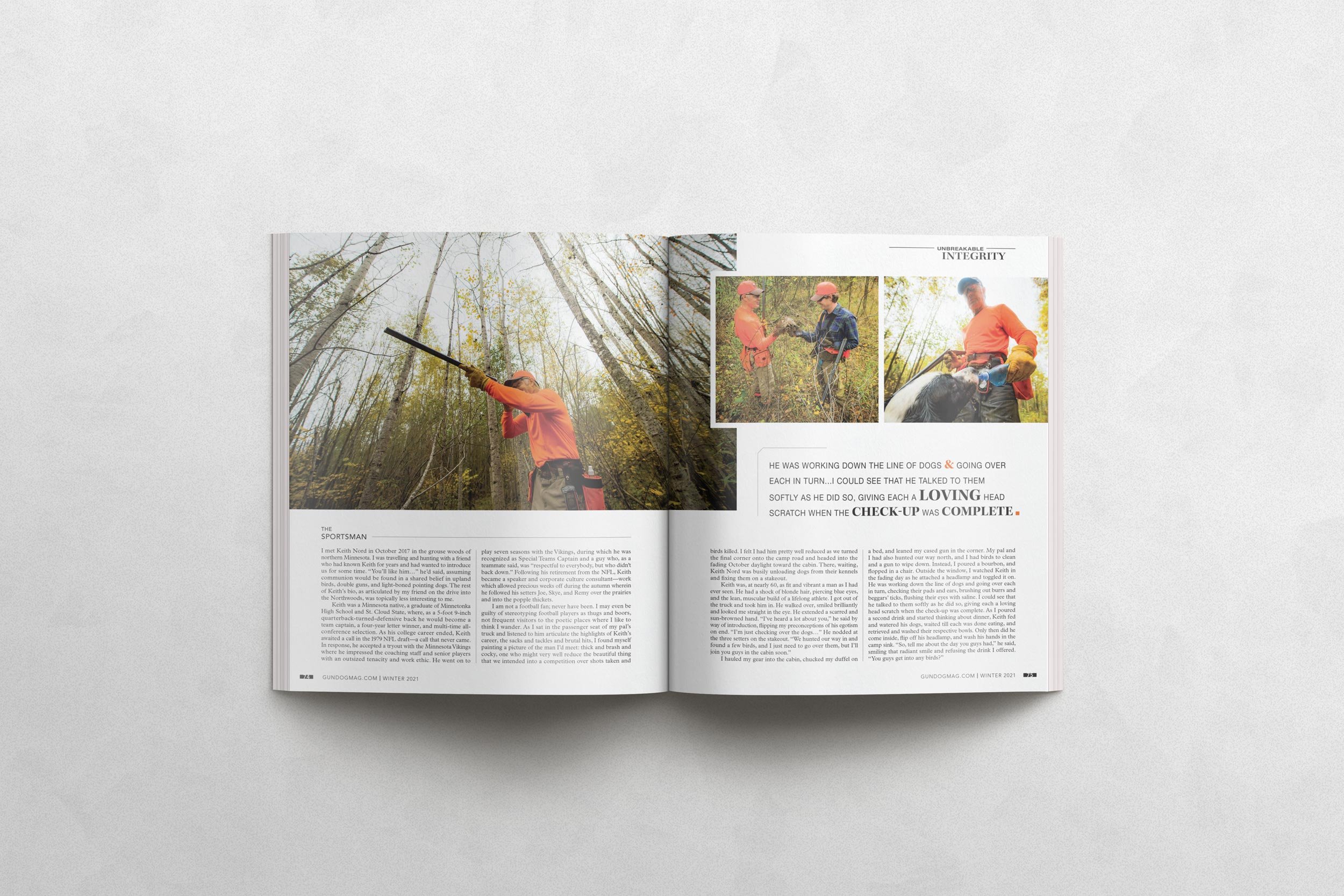

I met Keith Nord in October 2017 in the grouse woods of northern Minnesota. I was travelling and hunting with a friend who had known Keith for years and had wanted to introduce us for some time. “You’ll like him…” he’d said, assuming communion would be found in a shared belief in upland birds, double guns, and light-boned pointing dogs. The rest of Keith’s bio, as articulated by my friend on the drive into the north woods, was topically less interesting to me.

Keith was a Minnesota native, a graduate of Minnetonka High School and St. Cloud State, where, as a 5-foot 9-inch quarterback-turned-defensive back he would become a team captain, a four-year letter winner, and multi-time all-conference selection. As his college career ended, Keith awaited a call in the 1979 NFL draft, a call that never came. In response he accepted a tryout with the Minnesota Vikings, where he impressed the coaching staff and senior players with an outsized tenacity and work ethic. He went on to play seven seasons with the Vikings, during which he was recognized as Special Teams Captain and a guy who, as a teammate said, was “respectful to everybody, but who didn't back down.” Following his retirement from the NFL, Keith became a speaker and corporate culture consultant, work which allowed precious weeks off during the autumn wherein he followed his setters Joe, Skye, and Remy over the prairies and into the popple thickets.

I am not a football fan; never have been. I may even be guilty of stereotyping football players as thugs and boors, not frequent visitors to the poetic places where I like to think I wander. As I sat in the passenger seat of my pal’s truck and listened to him articulate the highlights of Keith’s career, the sacks and tackles and brutal hits, I found myself painting a picture of the man I’d meet: thick and brash and cocky, one who might very well reduce the beautiful thing that we intended into a competition over shots taken and birds killed. I felt I had him pretty well reduced as we turned the final corner onto the camp road and headed into fading October daylight toward the cabin. There, waiting, Keith Nord was busily unloading dogs from their kennels and fixing them on a stakeout.

Keith was, at nearly 60, as fit and vibrant a man as I had ever seen. He had a shock of blonde hair, piercing blue eyes, and the lean, muscular build of a lifelong athlete. I got out of the truck and took him in. He walked over, smiled brilliantly and looked me straight in the eye. He extended a scarred and sun-browned hand. “I’ve heard a lot about you,” he said by way of introduction, flipping my preconceptions of his egotism on end. “I’m just checking over the dogs…” He nodded at the three setters on the stakeout. “We hunted our way in and found a few birds, and I just need to go over them, but I’ll join you guys in the cabin soon.”

I hauled my gear into the cabin, chucked my duffel on a bed, leaned my cased gun in the corner. My pal and I had also hunted our way north, and I had birds to clean and a gun to wipe down. Instead, I poured a bourbon, and flopped in a chair. Outside the window, I watched Keith in the fading day as he attached a headlamp and toggled it on. He was working down the line of dogs and going over each in turn, checking their pads and ears, brushing out burrs and beggars’ ticks, flushing their eyes with saline. I could see that he talked to them softly as he did so, giving each a loving head scratch when the check-up was complete. As I poured a second drink and started thinking about dinner, Keith fed and watered his dogs, waited till each was done eating, and retrieved and washed their respective bowls. Only then did he come inside, flip off his headlamp, and wash his hands in the camp sink. “So, tell me about the day you guys had,” he said, smiling that radiant smile and refusing the drink I offered. “You guys get into any birds?”

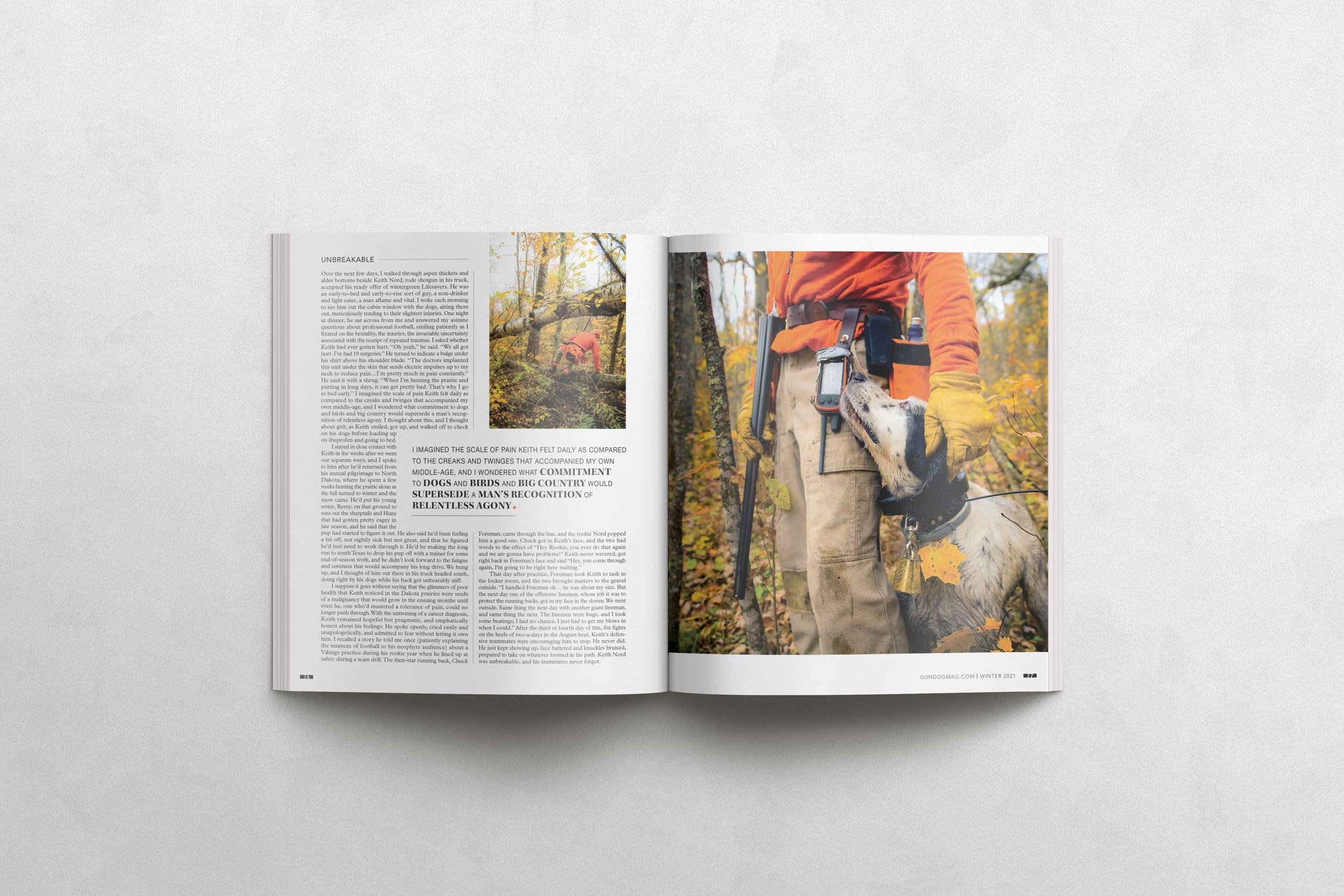

Over the next few days, I walked through aspens thickets and alder bottoms beside Keith Nord, rode shotgun in his truck, accepted his ready offer of wintergreen Lifesavers. He was an early-to-bed and early-to-rise sort of guy, a non-drinker and light eater, a man aflame and vital. I woke each morning to see him out the cabin window with the dogs, airing them out, meticulously tending to their slightest injuries. One night at dinner, he sat across from me and answered my asinine questions about professional football, smiling patiently as I fixated on the brutality, the injuries, the invariable uncertainty associated with the receipt of repeated traumas. I asked whether Keith had ever gotten hurt. “Oh yeah,” he said. “We all got hurt. I’ve had 19 surgeries.” He turned to indicate a bulge under his shirt above his shoulder blade. “The doctors implanted this unit under the skin that sends electric impulses up to my neck to reduce pain… I’m pretty much in pain constantly.” He said it with a shrug. “When I’m hunting the prairie and putting in long days, it can get pretty bad. That’s why I go to bed early.” I imagined the scale of pain Keith felt daily as compared to the creaks and twinges that accompanied my own middle-age, and I wondered what commitment to dogs and birds and big country would supersede a man’s recognition of relentless agony. I thought about this, and I thought about grit, as Keith smiled, got up, and walked off to check on his dogs before loading up on ibuprofen and going to bed.

I stayed in close contact with Keith in the weeks after we went our separate ways, and I spoke to him after he’d returned from his annual pilgrimage to North Dakota, where he spent a few weeks hunting the prairie alone as the fall turned to winter and the snow came. He’d put his young setter Remy on that ground to suss out the sharptails and huns that had gotten pretty cagey in late season, and he said that the pup had started to figure it out. He also said he’d been feeling a bit off, not rightly sick but not great, and that he figured he’d just need to work through it. He’d be making the long run to south Texas to drop is pup off with a trainer for some end-of-season work, and he didn’t look forward to the fatigue and soreness that would accompany his long drive. We hung up, and I thought of him out there in his truck headed south, doing right by his dogs while his back got unbearably stiff.

I suppose it goes without saying that the glimmers of poor health that Keith noticed in the Dakota prairies were seeds of a malignancy that would grow in the ensuing months until even he, one who’d mastered a tolerance of pain, could no longer push through. With the untwining of a cancer diagnosis, Keith remained hopeful but pragmatic, and emphatically honest about his feelings. He spoke openly, cried easily and unapologetically, and admitted to fear without letting it own him. I recalled a story he told me once (patiently explaining the nuances of football to his neophyte audience) about a Vikings practice during his rookie year when he lined up at safety during a team drill. The then-star running back Chuck Foreman came through the line, and the rookie Nord popped him a good one. Chuck got in Keith’s face, and the two had words to the effect of “Hey Rookie, you ever do that again and we are gonna have problems!” Keith never wavered, got right back in Foreman’s face and said “Hey, you come through again, I'm going to be right here waiting...”

That day after practice, Foreman took Keith to task in the locker room, and the two brought matters to the gravel outside. “I handled Foreman ok… he was about my size. But the next day one of the offensive linemen, whose job it was to protect the running backs, got in my face in the dorms. We went outside. Same thing the next day with another giant lineman, and same thing the next. The linemen were huge, and I took some beatings; I had no chance, I just had to get my blows in when I could.” After the 3rd or 4th day of this, fist fights on the heels of two-a-days in the August heat, Keith’s defensive teammates were encouraging him to stop. He never did. He just kept showing up, face battered and knuckles bruised, prepared to take on whatever loomed in his path. Keith Nord was unbreakable, and his teammates never forgot.

But cancer was another adversary altogether. Keith took those daily beatings with signature grit, but I suppose the inhumanity of that illness is the flippancy with which it toys with men, even the strongest ones, killing some and letting others go free. We talked a good deal in those days of late summer, talked about getting together for a walk in the grouse woods, something to look forward to. But Keith was tough and he was a pragmatist, and mostly what we talked about was contingencies. He spoke about his wife and children, the plans for their security, who would blaze a path for his youngest son into his own uplands. And he talked at length about the future of his dogs, whom he worried over steadily until the very end. “Please,” he said on one of our many talks, “the older two should stay at home… their best days are over. But the pup needs to go to somewhere that he will be loved and hunted. I want him with people that will get him out on the prairie to do what he was born to do. Please, make sure he is ok.”

When I think about integrity, I think about Keith Nord. I think about conviction, not the obstinate kind, but the kind that compels a man to do what he sees as right through eyes filled with empathy and love. I think about self-sacrifice in the face of fear and pain, and I think about the cost and the benefit of doing whatever you must to make sure your team is cared for. I think about bodies that never stop hurting, and how wheat fields and Dakota horizons and dogs on point can become analgesic. And I think about the simplest gestures - the gentle flushing of a setter’s eyes, the thorough washing of his food bowl – that don’t require recognition or platitudes.

Recognition or platitudes… my friend Keith Nord didn’t go looking for those either. He had integrity, and that was enough. I miss him.

First Published Gun Dog Magazine