The Guide’s Life

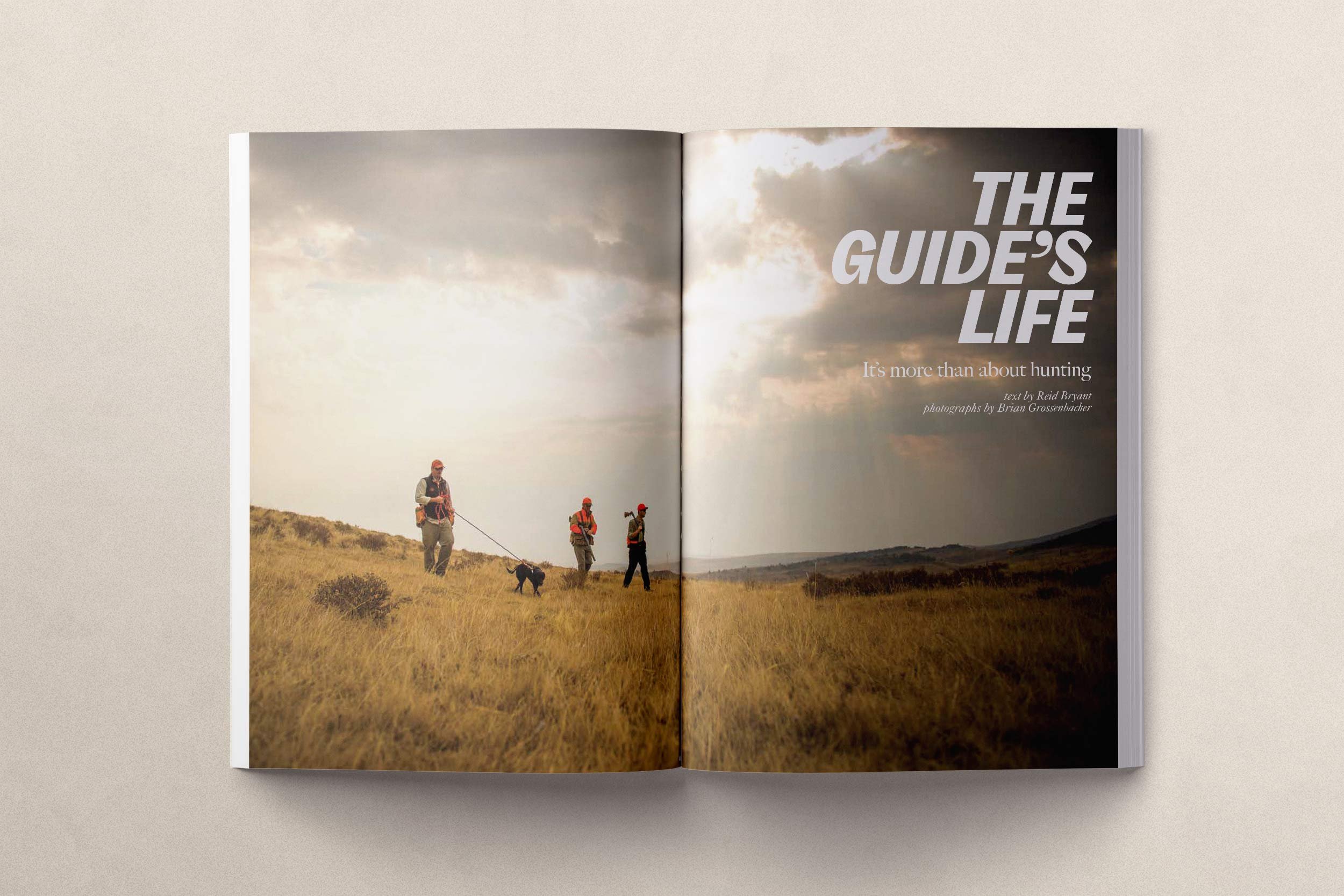

On a hot June day this past summer I reached out to my friend Ryan O’Shaughnessy, owner and head guide of West Texas Quail Outfitters, in Alpine, Texas. Ryan is a guy who is always good for a chat, especially when my bird season feels a lifetime away and some concrete travel plans for a journey west are just what the doctor ordered.

Ryan didn’t answer.

An hour or so later a text message came through extending an apology and a creditable excuse: “Sorry, buddy, couldn’t pick up. A hundred degrees here, and I am busy welding up some new dog kennels. Catch up later this week?”

Over the course of our friendship and after several forays together in pursuit of scaled quail, I have come to regard Ryan as a living example of the consummate upland guide. He is polite and professional with an old-world charm, kind to his dogs and almost uncannily capable of locating birds in the near lunar landscape of the West Texas desert. As is true of many full-time guides, however, the hard and soft skills that are less immediate color the work of a true Renaissance man—one who exemplifies the totality of the upland-guide profession in practice. Ryan is at once a welder, a dog trainer, a naturalist, a businessman, a psychologist, a coach and an entertainer. In the course of a given day in or out of the season, he may be called upon to treat snakebite, navigate border relations or help repair the ranch road of a hardened Texas cattleman. He can table a field lunch that requires three unique forks and a soup course, and he can tell you the taxonomic classification of the thornbush from which he is simultaneously disentangling you. And he often does all of this before going home late at night to feed a kennel full of pointing dogs, tuck in his daughters and listen attentively to the highs and lows of his wife, Kara’s, busy day.

In spending time with Ryan, in watching him work, I have come to appreciate the guide’s life for its layered demands. As a hunter, traveler and one who has followed great guides into breathtaking places, I have tried to appreciate, at least academically, both the romance and the challenge of the complex role that is Ryan’s vocation. In hoping, trying, to be a better client, I’ve gained some insight by asking many of the guides I have encountered some tough, or at least revealing, questions about the realities that take place behind the curtain. I have wanted to understand what occurs in the odd hours that I don’t witness but nonetheless profit from. Only then will I be able to fully grasp the breadth and depth of the guided experience, and only then will I be able to value it adequately. In summary, I have categorized the following insights concerning guides—the unsung heroes of the upland space—and the demands they encounter in the service of surprising, delighting and caring for those who follow them. Consider, therefore, the following:

Dogs: A Financial, Physical and Emotional Responsibility

An upland guide is only as successful as the dogs he or she puts down, and all the good guides I have known see their dogs less as tools and more as beloved partners. Dogs, of course, require care, training and handling on a schedule that is immutable every day of the year. Guides who work a full season, especially a prolonged preserve season, cannot run the same dogs day in and day out and must additionally plan for the unforeseen injuries that can waylay some number of their string. As a rule of thumb—and depending on the region, the bird species hunted and the season length—a single guide will have a minimum of four to eight dogs in regular rotation. Such a string takes considerable management.

Four to eight canine athletes require daily exercise; kennels that are secure, clean and climate controlled; premium food and regular vet checks. Each dog comes with a purchase price and accumulates hours’ worth of training before he or she is ready to hunt with clients. Given their drive and the unforgiving places in which they hunt, gundogs are prone to a host of injuries that require vet attention and rehab time. From a strictly financial standpoint, a string of gundogs will cost a guide many thousands of dollars each year.

Mike Goldsmith, who guides at Joshua Creek Ranch in Boerne, Texas, breaks down the financial realities thus: “Even if I do the training myself, it is expensive, equating to around $1,000 a month for seven to nine months for a dog that costs upward of $1,000 to begin with. A finished gundog amounts to about $10,000 to start. Then there is dog-training equipment, such as collars. A three-dog unit runs about $1,500, and you have to have back-up gear ready. Then there is food. Everyone asks how much feed I go through. With nine dogs, roughly 120 pounds every week; and I buy food by the pallet! Supplemental feed to maintain weight during hunting season must be considered as an additional cost. Transportation needs for dogs add another dimension, whether you choose a custom trailer [$10,000-plus] or a dog rig [$30,000-plus] that can safely get dogs in and out of the field. And when things go wrong, dog surgeries are not cheap. TPLO [elbow] surgery runs about $3,000, and ACL issues run about the same or more. Add to the list daily supplements, monthly flea-and-tick and heartworm, plus all the yearly shots . . . .” Let’s just say it gets expensive.

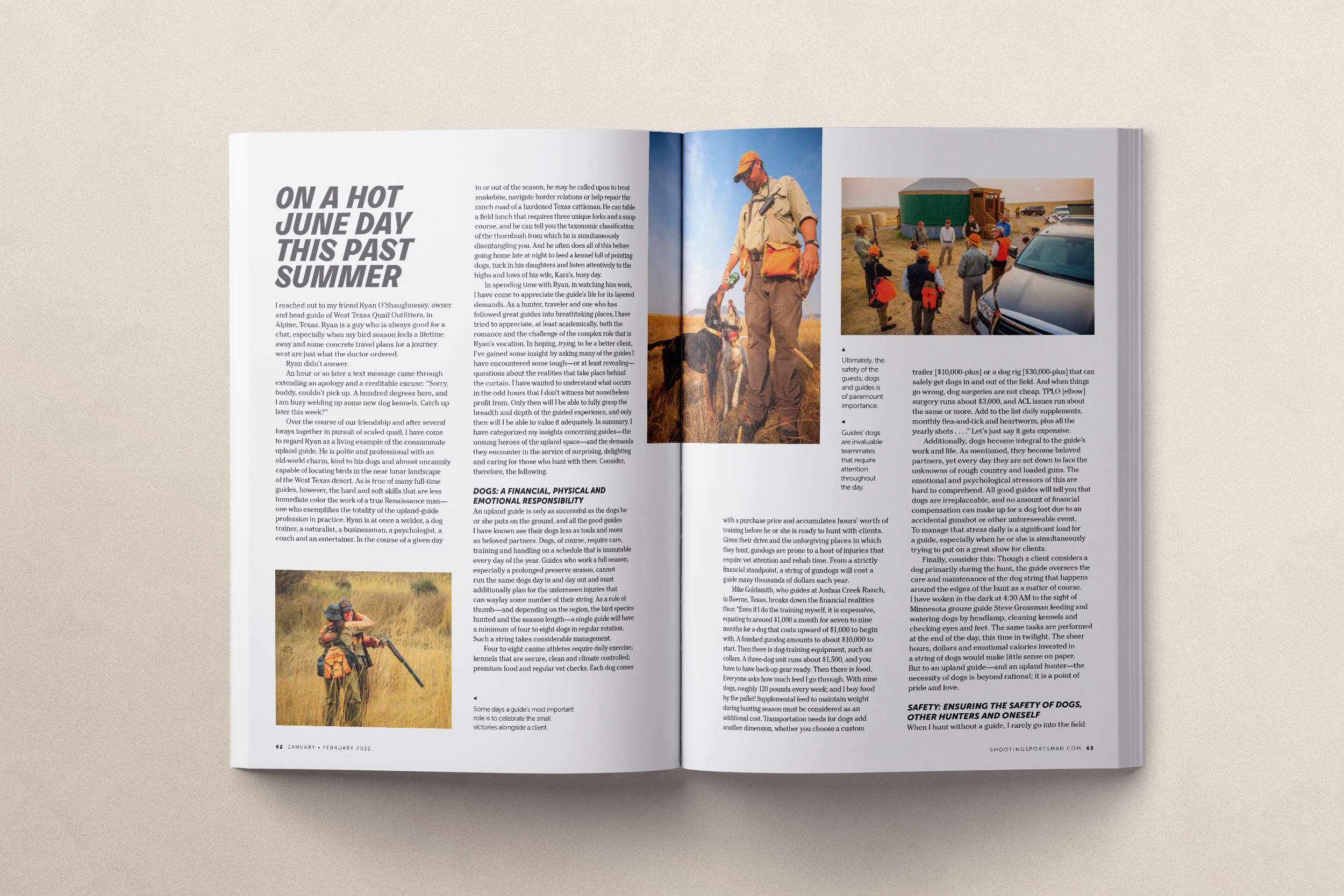

Additionally, dogs become integral to the guide’s work and life. As mentioned, they become beloved partners, yet every day they are set down to face the unknowns of rough country and loaded guns. The emotional and psychological stressors of this are hard to comprehend. All good guides will tell you that dogs are irreplaceable, and no amount of financial compensation can make up for a dog lost due to a gunshot, accident or other unforeseeable event. To manage that stress daily is a significant load for a guide, especially when he or she is simultaneously trying to put on a great show for clients.

Finally, consider this: Though a client considers a dog primarily during the hunt, the guide oversees the care and maintenance of the dog string that happens around the edges of the hunt as a matter of course. I have woken at dawn to watch Minnesota grouse guide Steve Grossman feeding and watering dogs, cleaning kennels, and checking eyes and feet. The same tasks are performed at the far end of the day, this time in twilight. The sheer hours, dollars and emotional calories invested in a string of dogs would make little sense on paper. But to an upland guide—and an upland hunter—the necessity of dogs is beyond rational; it is a point of pride and love.

Safety: Ensuring the Safety of Dogs, Other Hunters and Oneself

When I hunt without a guide, I rarely go into the field with folks I don’t know well. I like to hunt alongside others who share my ethics, who understand muzzle control and safe gun handling and who I can rely on to never take questionable shots around me or my dogs. I know that many of my companions do the same and would rather hunt alone than with someone they do not know or trust.

An upland guide, however, regularly goes into the field with perfect strangers. It is the guide’s job to be both hyper-vigilant and instructive—to choreograph the hunt with an eye to safety first and success second. Guide Rich Coe at Idaho’s Flying B Ranch relates how frequently he hears clients claim a lifetime of hunting experience only to see them take questionable shots over dogs, other hunters or guides. “It’s hardest when the client thinks he knows more than the guide,” Coe said. “I give a detailed safety talk before we go into the field, and it still amazes me how frequently I will hear a safety click off while the dogs on point are still 100 yards ahead; or I’ll turn to find myself looking at the muzzle of a closed gun carried over the shoulder; or I’ll get my bell rung by a muzzle blast. I try to be polite, but safety is non-negotiable.” Guides—the ones who persist—are known to call off hunts when safe practices take second seat.

Guiding is a service industry, and all guides set out to provide an enjoyable time for their clients. That said, a professional upland guide likely spends more hours in the field during a season than most hunters do in a lifetime. They simply know more than the clients do, which is only fair by virtue of their experience. If they see something that makes them feel unsafe, or if they need to speak with a client about muzzle control, it is the client’s responsibility to defer to their experience. The guide and the guide’s dogs are in a vulnerable position every day, and recognition of their safety parameters are a small price to pay for their comfort.

Prior Planning: Hours of Preparation

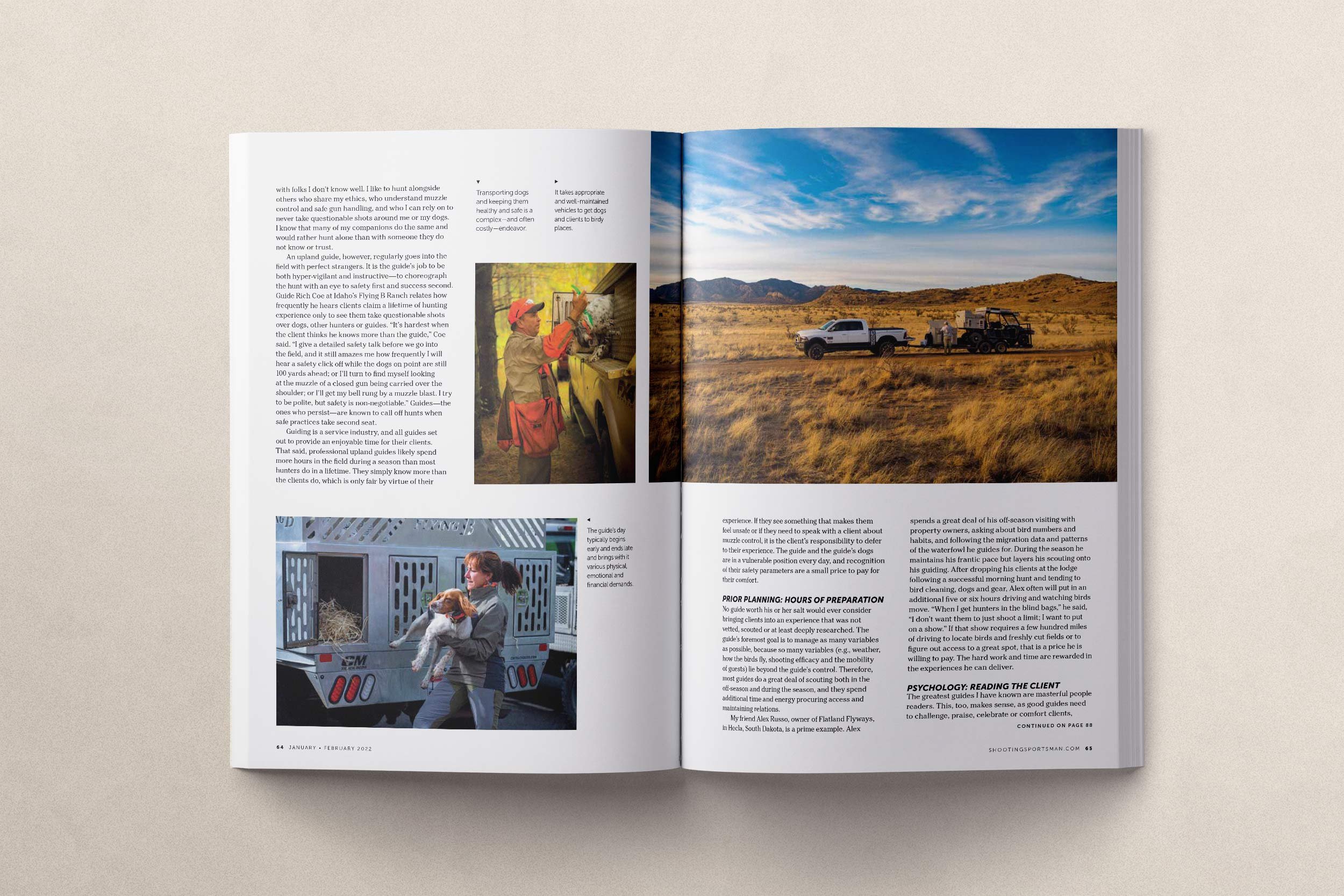

No guide worth his or her salt would ever consider bringing clients into an experience that was not vetted, scouted or at least deeply researched. The guide’s foremost goal is to manage as many variables as possible, because so many variables (e.g., weather, how the birds fly, the shooting abilities of the guests) lie beyond the guide’s control. Therefore, most guides do a great deal of scouting both in the off-season and during the season, and they spend additional time and energy procuring access and maintaining relations.

My friend Alex Russo, owner of Flatland Flyways, in Hecla, South Dakota, is a prime example. Alex spends a great deal of his off-season visiting with property owners, asking about bird numbers and habits, and following the migration data and patterns of the waterfowl he guides for. During the season he maintains his frantic pace but layers his scouting onto his guiding. After dropping his clients at the lodge following a successful morning hunt and tending to bird cleaning, dogs and gear, Alex often will put in an additional five or six hours driving and watching birds move. “When I get hunters in the blind bags,” he said, “I don’t want them to just shoot a limit; I want to put on a show.” If that show requires a few hundred miles of driving to locate birds and freshly cut fields or to figure out access to a great spot, that is a price he is willing to pay. The hard work and time are rewarded in the experiences he can deliver.

Psychology: Reading the Client

The greatest guides I have known are masterful people readers. This, too, makes sense, as good guides need to challenge, praise, celebrate or comfort clients, depending on the situation. Good guides know just what to do and say—and when to do and say it. But they also know that the personal, human experience of hunting should be about something greater than a full bag.

BJ Walle, also of Idaho, described this to me on an uphill walk in pursuit of an uncooperative covey of Huns. “I like to make sure I challenge folks,” he said, pacing himself against my slow steps. “I want them to shoot birds, but I also want them to see themselves do something they didn’t think they could—or would—do.”

This perspective on guiding was revelatory for me. What BJ saw as his primary charge was to get a client safely onto birds, but his more important job was to help a client grow, to broaden his or her frame of reference, and to superimpose the act of hunting onto a larger backdrop of self-discovery. It may seem like a bit of a reach, but good guides don’t see their roles as something mechanical or obvious; they look for opportunities to make lasting impacts and to help clients recognize those impacts while they’re occurring.

All of this comes naturally to guides who have the ability to read their clients. They will recognize intuitively how hard to push, when it is OK to joke, and when a bit of extra stroking is required. Clients generally recognize, admittedly or not, that in the hunting space they are somewhat out of their element; they may bring with them a degree of anxiety, inferiority or competitiveness, and all of these feelings must be massaged by the guide to ensure a successful, safe and enjoyable hunt. By doing so, guides serve as amateur psychologists.

Lifestyle: The Realities of the Guide Life

Over the years I have noticed that, as a client on a guided trip, I bring a certain perspective and load of expectations into a hunt. My guided days often are contextualized as vacations or free time, strictly recreational, and events that I have anticipated and saved for. Even at my most self-aware, I bring to the experience a degree of expectation for both the hunt and the guide facilitating it, and I often assume, perhaps irrationally, that my level of investment and enthusiasm should be shared by the guide.

Good guides know this; they have an aptitude for telling great jokes and stories, for entertaining from pick-up all the way through dinner and drinks, and for going the extra mile to put a client on shootable birds. Unlike a guide, however, after a few days in the field I go home and begin anticipating the next adventure a year or two out. I am typically exhausted. The guide, however, has another client filling my space as soon as I depart—a client who is similarly expecting an entertainer, a bird finder, a joke teller and a designated driver to buttress his or her anticipated vacation. This is the guide’s life.

The guide day regularly begins well before dawn and ends late at night. It brings with it physical, financial and emotional demands. Guides don’t have the luxury of “off days”; they cannot afford to be distracted by the fight they have had with their spouse or the illness plaguing an aging parent. These personal struggles must be compartmentalized. Guides need to be fun dinner guests but can’t be hung over the next morning. They need to recognize and celebrate the innate joy in moments that they have seen play out a thousand times. And what energy is left in the tank at the end of a guide day needs to be thoughtfully doled out to friends, spouses and family—all of whom are waiting at home, often thinking that the guide’s day is little more than a perpetual vacation. Sadly, the commensurate and reciprocal attention is often not sufficient to maintain relationships.

Again my pal Rich Coe said it well: “People sometimes forget that a guide has a personal life too. I have several friends who have been divorced on account of this lifestyle, and as a single parent it is a hard job to have. I can’t always leave a hunt to pick up a sick child from daycare. But clients don’t want to hear about that kind of BS, and I get that. Everybody has their bad days at home, and you can’t bring that to your clients. As a guide, it’s different. In a cubicle you can put your head down and be upset and hide all that. We don’t get that luxury.”

The demands of the guide’s life are real. Long days; physical exposure to heat, cold and sun; and big walks in rough country. Time away from family and a steady hum of anxiety about personal safety—all of this superseded by the need to create some degree of theater for clients. It’s a big, complicated job and one for which the pay barely covers the expenses.

So why do they do it? What is the kernel of this life that keeps them doing it year in and year out?

‘It’s What I Love’

The short answer to the above questions is that resoundingly guides do what they do for the love of it. Said Rich Coe: “It becomes an obsession.” They love the dogs and the open country, the people they meet and the magical experiences they get to deliver. Many of them could do other things. Ryan O’Shaughnessy, the guide-welder-conservationist referenced earlier, holds a PhD and an MBA but spends his days looking for little running birds among the cholla. So what keeps him in the game? Ryan is thoughtful. “I guide because of the people,” he said. “When I hear young folks say they want to guide because they like hunting or animals, I cringe. Sure, you must love hunting, but that motivates about ten percent of the job. The other ninety percent revolves around people.”

He chews on those words for a time, considering the root of what motivates him. “You know, every day I get to be a part of someone’s precious vacation, their favorite thing to do, the moment they have been looking forward to all year. It’s a privilege to be part of that. It’s what I love.”

The good guides get it. Simple as that.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine