Straight Priorities

The entry gateway of a western ranch is, in a sense, a piece of functional folk art. Some gates are monuments, elaborations of cattle brands and monograms and massive timber joinery. Those gates are the superficial sort, serving the primary purpose of stroking the egos that own the ground beyond. Passing through such a gate, the old expression “all hat and no cattle” comes to mind.

Conversely, I have turned off several one-lane highways and through some simple gateposts only to encounter places of unparalleled majesty, land whose value can’t be quantified in dollars and cents. More often than not, these ranches are tended by owners (a few billionaires among them) wearing work gloves and dusty Wranglers, folks whose pride is banked in the ability to handle a lariat, quarter a pronghorn, and navigate the finer points of grazing and water rights. I am always comforted by such folks, as I am similarly grateful for a tidy, sturdy, and simple ranch gate; such entities exemplify confidence in good ground, hard work, and humility; in days spent close to the land that don’t require ostentation. Those are priorities I appreciate.

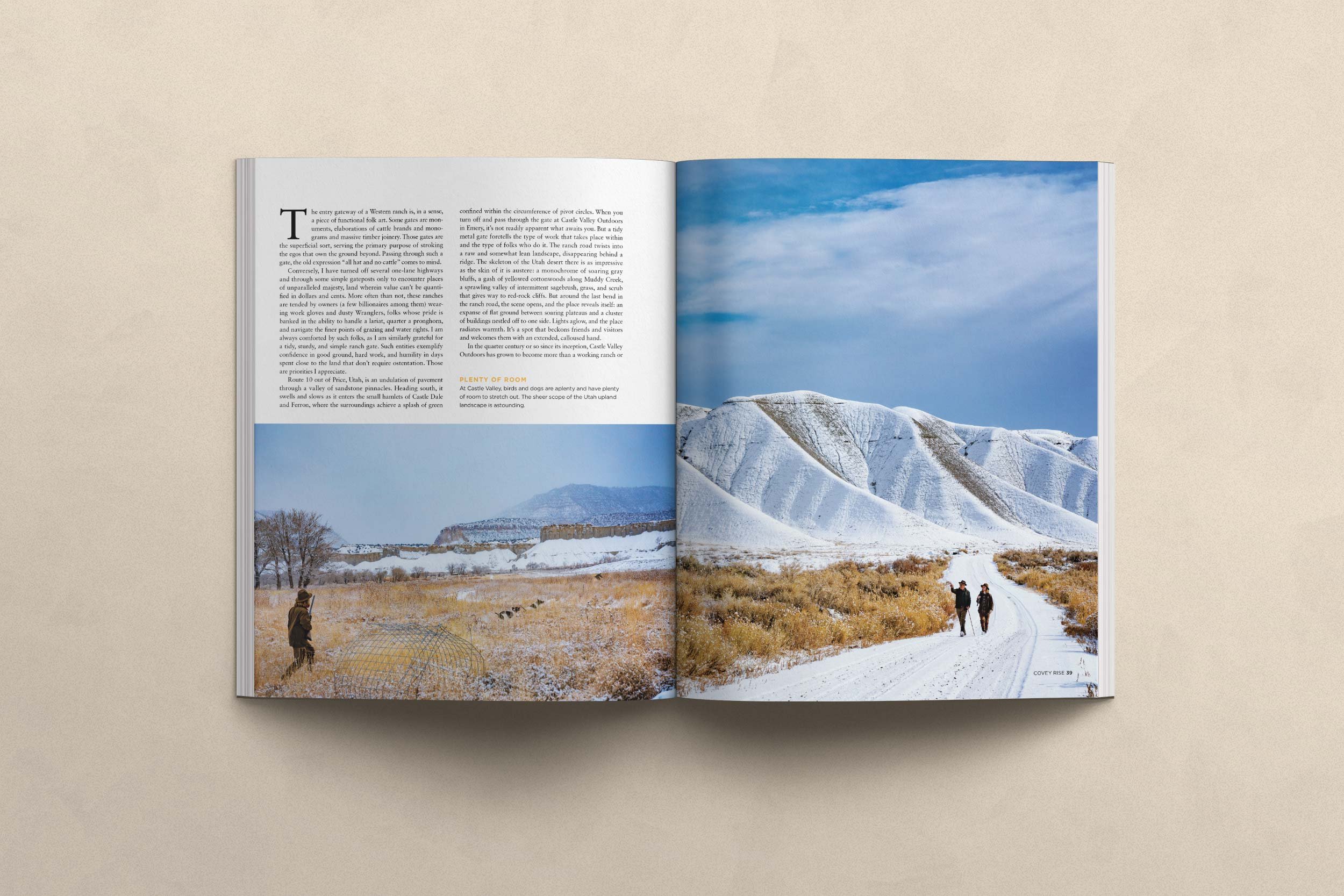

Rt 10 out of Price, Utah is an undulation of pavement through a valley of sandstone pinnacles. Heading south, it swells and slows as it enters the small hamlets of Castle Dale and Ferron, where the surroundings achieve a splash of green confined within the circumference of pivot circles. When you turn off Rt. 10 and pass through the gate at Castle Valley Outdoors in Emery, it’s not readily apparent what awaits you, but a tidy metal gate foretells the type of work that takes place within, and the type of folks who do it. The ranch road twists into a raw and somewhat lean landscape, disappearing behind a ridge. The skeleton of the Utah desert there is as impressive as the skin of it is austere: a monochrome of soaring gray bluffs, a gash of yellowed cottonwoods along Muddy Creek, a sprawling valley of intermittent sagebrush, grass, and scrub that gives away to red-rock cliffs. But around the last bend in the ranch road, the scene opens up and the place reveals itself: an expanse of flat ground between soaring plateaus and a cluster of buildings nestled off to one side. Lights aglow, the place radiates warmth. It’s a spot that beckons friends and visitors and welcomes them with an extended, calloused hand.

In the quarter century or so since its inception, Castle Valley Outdoors has grown to become more than a working ranch or a bird-hunting destination. It is appropriately the public-facing expression of the Johnson Family, their pride of place, conviction in land and people, and the gifts that both bestow. The property is owned by Woody Johnson, whose familial roots probe the rocky soils of Emery County. Johnson’s Danish ancestors made their way west during the Mormon migration and homesteaded, an act of faith that is itself impressive irrespective of the success they’d conjure out of the bottomlands.

Woody’s father Glendon was a beloved local character. He was born not far from Castle Valley Outdoors in the small enclave of Cleveland, UT. Though both Glendon and Woody had legal and business careers that would carry them east, both maintained a solid presence in the region as young men, cowboy-ing and working ranches, hunting and fishing, living seasons on horseback and under the open skies. In the early 70s, Glendon and his brother Frank acquired a string of ranches through Utah and Colorado, a holding that was to be lost in the real-estate crash of the later 70s. With the dissolution of the property holdings, Glendon retained a small mountain property and continued with his professional career. His love of the Utah desert ranchland never waned, however; through the next decade he kept an eye on one piece that had slipped through his fingers in the crash, the piece he’d owned off Rt. 10 in Emery that straddled Muddy Creek. It was there that the towering sandstone “castle” for which the region was named interrupted the sky, and there that the Rochester Panel of Fremont petroglyphs told stories a thousand years old.

More recent history tells a wonderful tale as well. After nearly a decade re-grouping and attending to other businesses, Glendon came back to build up a land holding and cattle operation. When the piece in Castle Valley came back to market in 1994, he and his son Woody were poised to recover it. With the acquisition, they named Glendon’s brother Frank ranch manager until a local factotum named Jim Fauver took over that position in 2000, overseeing grounds which have grown with time to comprise more than 12,000 acres. Jim had been the county tax assessor, but knew ranch and farm matters too, and had a background in architecture. He’d also maintained a business rearing pheasants, guiding bird hunters, and training gundogs on his own small holding in the area, and these additional proficiencies suited the Johnson gentlemen just fine. They encouraged Jim to put together a few hunts for family and friends on the Emery property. It was a fortuitous start. Fauver’s enthusiasm and skills coupled with the magnificence of the setting to make for a bird hunt that was not readily forgotten, and those friends lucky enough to hunt the Johnson place told their friends what they’d experienced. The rest unfurled organically. Soon a full guide staff and kennel were established, and Fauver was tasked with the restoration of the pioneer homestead, then the construction of some small sleeping cabins, and finally a full-blown Lodge in 2004. With Endorsement by the Orvis Company in 2005, Castle Valley Outdoors became a destination for the discriminating, traveling wingshooter. Wonderfully, however, it never lost its sense of self or the origins from which it evolved; both Woody and Glendon Johnson made sure that the place was comfortable and welcoming, and the hunting experience was as authentic as the wild western landscape upon which it took place. They made sure to retain a steady presence there in their work gloves and dusty Wranglers, encouraging guests to do the same.

*

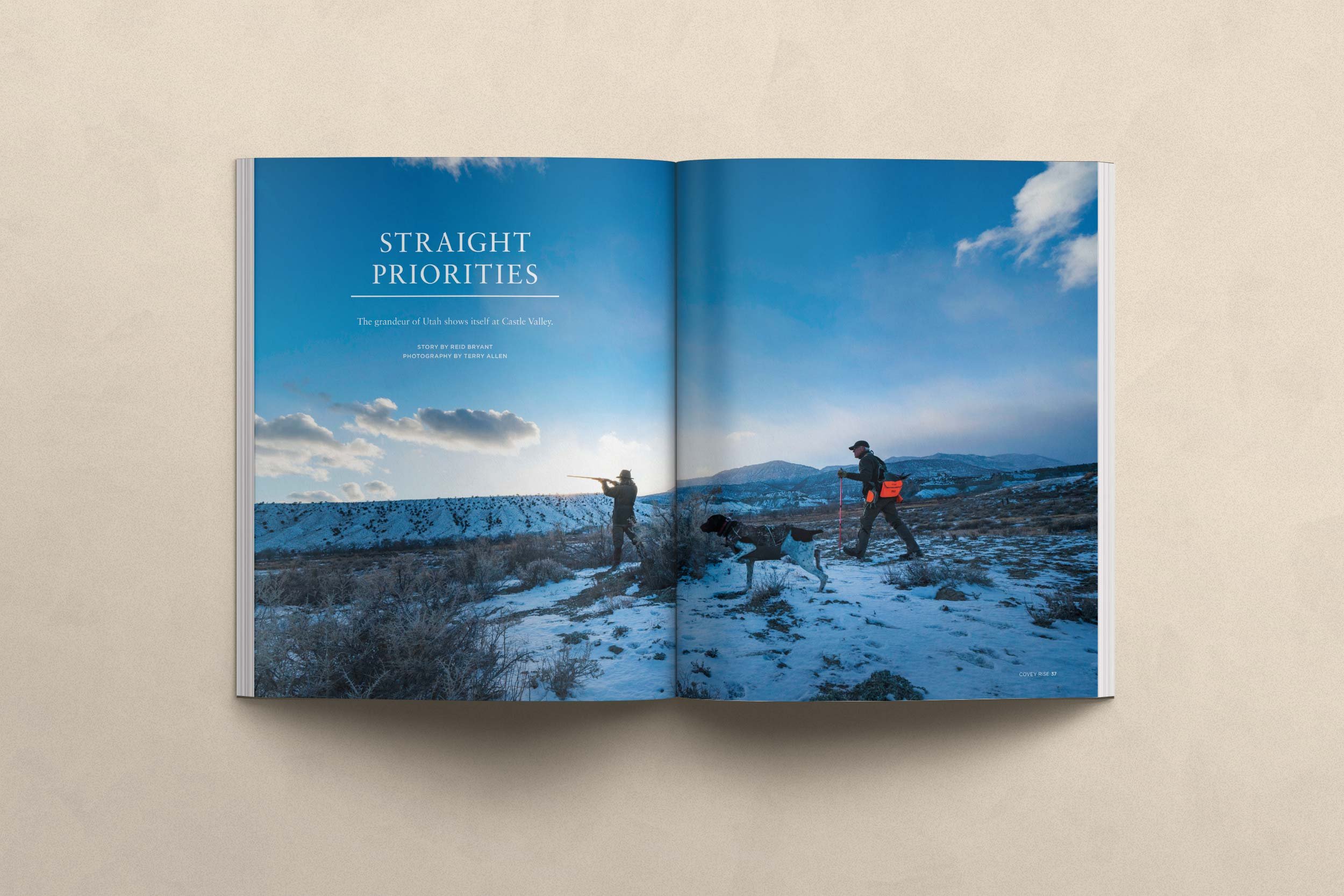

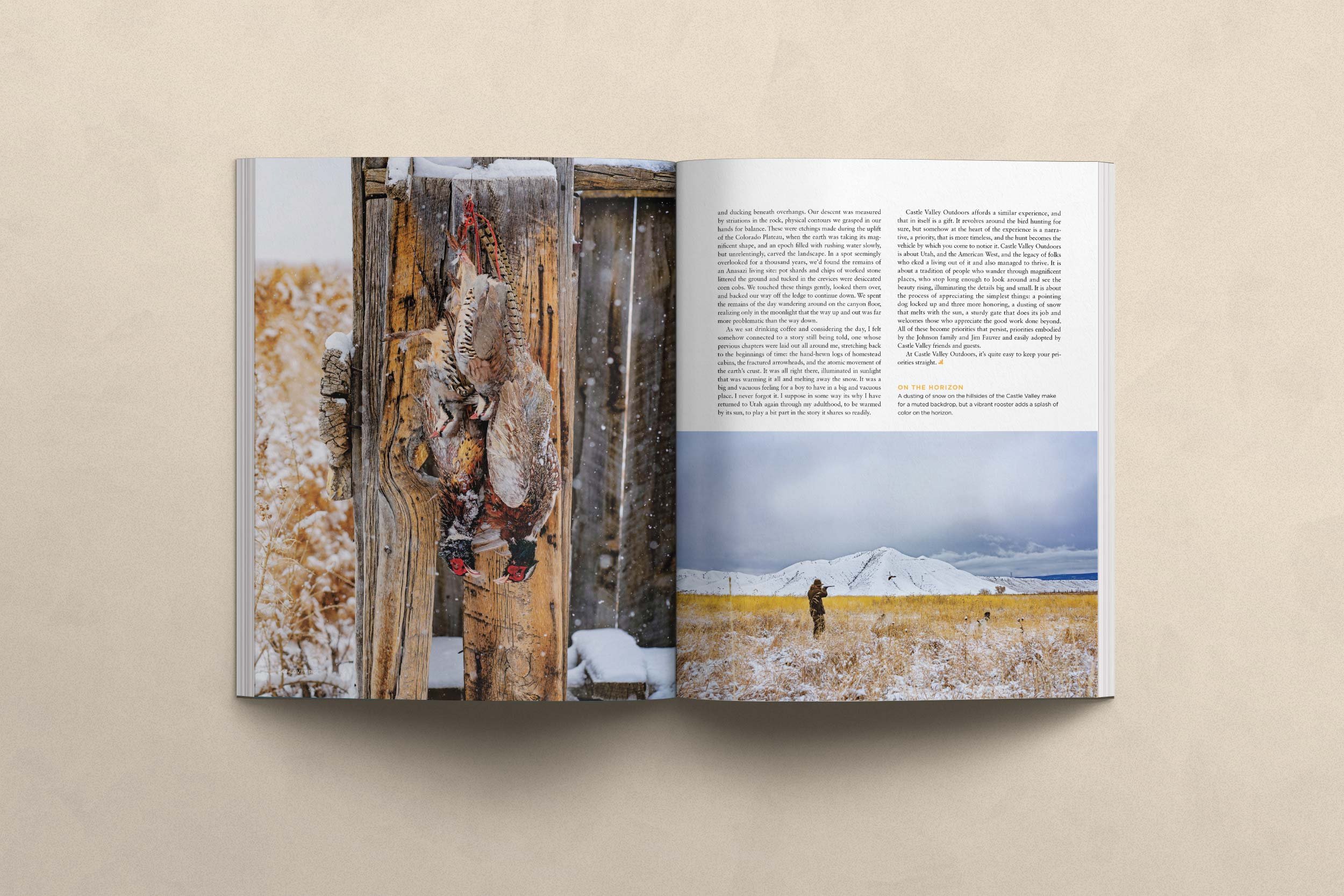

What strikes you about Castle Valley Outdoors is the immediacy of a hunting experience juxtaposed against the stunning backdrop of Utah’s topography. Given a dusting of snow, it becomes all the more radiant, whites and golds against a sweep of blue, and all else muted in between. What brings in color is a swatch of rooster feathers rising ahead of a point, radiating skyward like Icarus only to be called back by a well-timed shot. The snow makes Castle Valley even softer and quieter than it had been before: footfalls land without a sound, and all motion is revealed in scuffles and breaths. At Castle Valley the guides run big strings of shorthairs as a rule, and they run them quiet, without bells or beepers to clutter the experience. It is not uncommon to see a dog work a runner while a bracemate swings around to pin on the upwind side, others honoring from the flanks. The ground lends itself to dogs that work the cover in front of them, sticking tight in the milo strips and grasses, ranging further in pursuit of those cagey birds that make the fringes and seek asylum on higher, rockier ground. There is shooting aplenty, for all tastes.

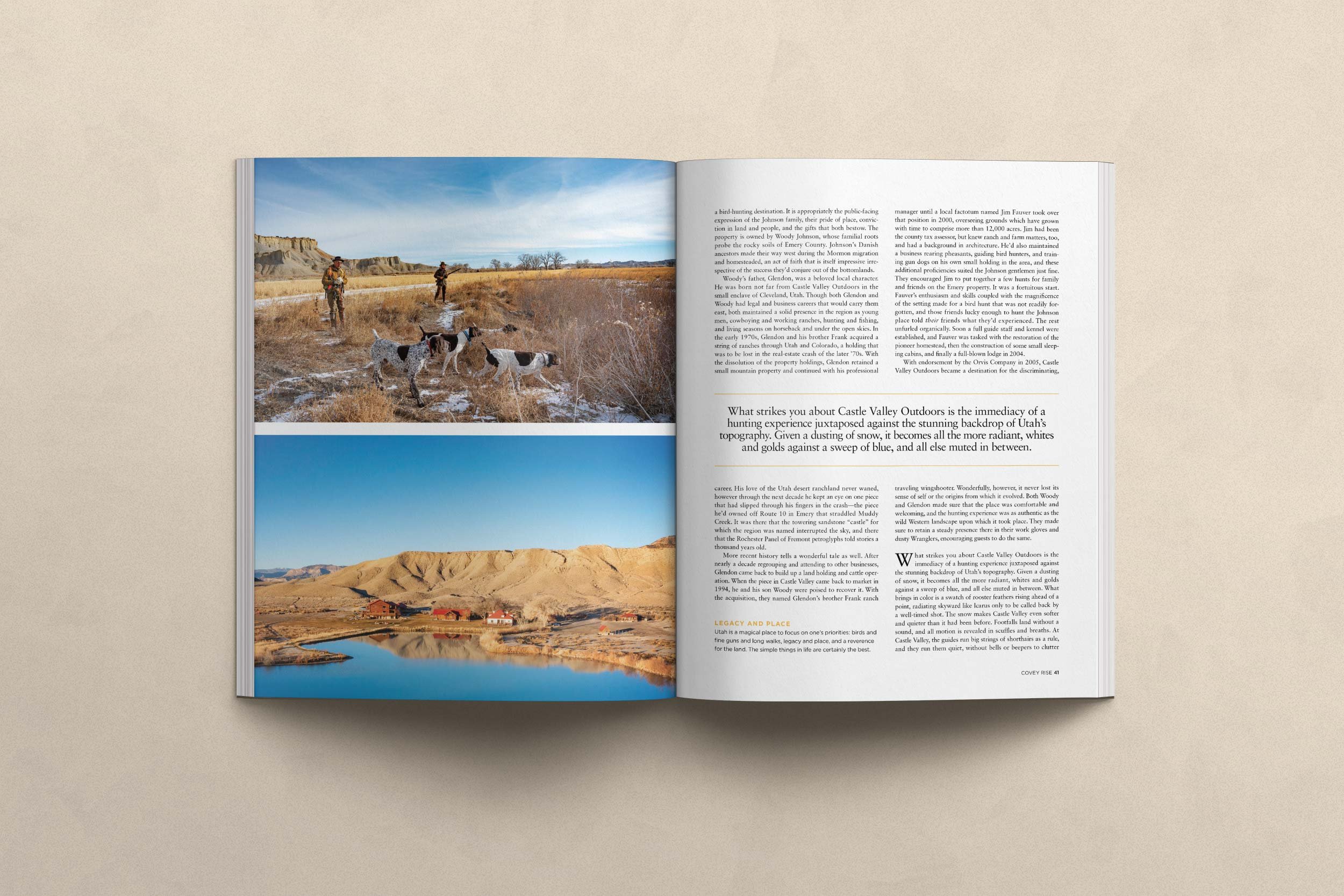

Though known primarily as a pheasant destination, the Castle Valley Outdoors has been, at times, host to bountiful populations of Gambel’s quail, and in recent years reproducing populations of chukars. Guests hunt crop fields and strips that give way to scrub hillsides and then to soaring sandstone bluffs and pinnacles, features that could not be climbed if one even cared to. The chukars and pheasants seem to pay little mind to the flying buttresses that create the valley; they get up and go with authority, and don’t leave much to chance. Those that follow, at least a little bit, will see the story of the place unfolding as they pass. Ancient, gnarled fruit trees stand barren with the season, though they once nourished generations of farm kids, who no doubt chased their own birds, albeit with simpler artillery. Across fence lines of faded wood and wire, chukars scramble and hunters pursue, stopping after a long-awaited flush to look back over the remains of a homestead cabin, abandoned for good only a few decades before.

The real beauty of the Castle Valley Outdoors experience is as much the hunting as the place in which it happens, and the realization that the land is largely unexplored, and only then by people who had good reason to be there. They say that in ancient times on that same piece of ground a community of a few thousand Fremont people made their living, hunting and gathering I’d imagine, collecting their experiences and recording a few on the red-rock walls. It’s a haunting and humbling realization to wander up the sidehills a piece and stand in a place where very few people have stood since that time before Christ; there aren’t many places left where such considerations are possible.

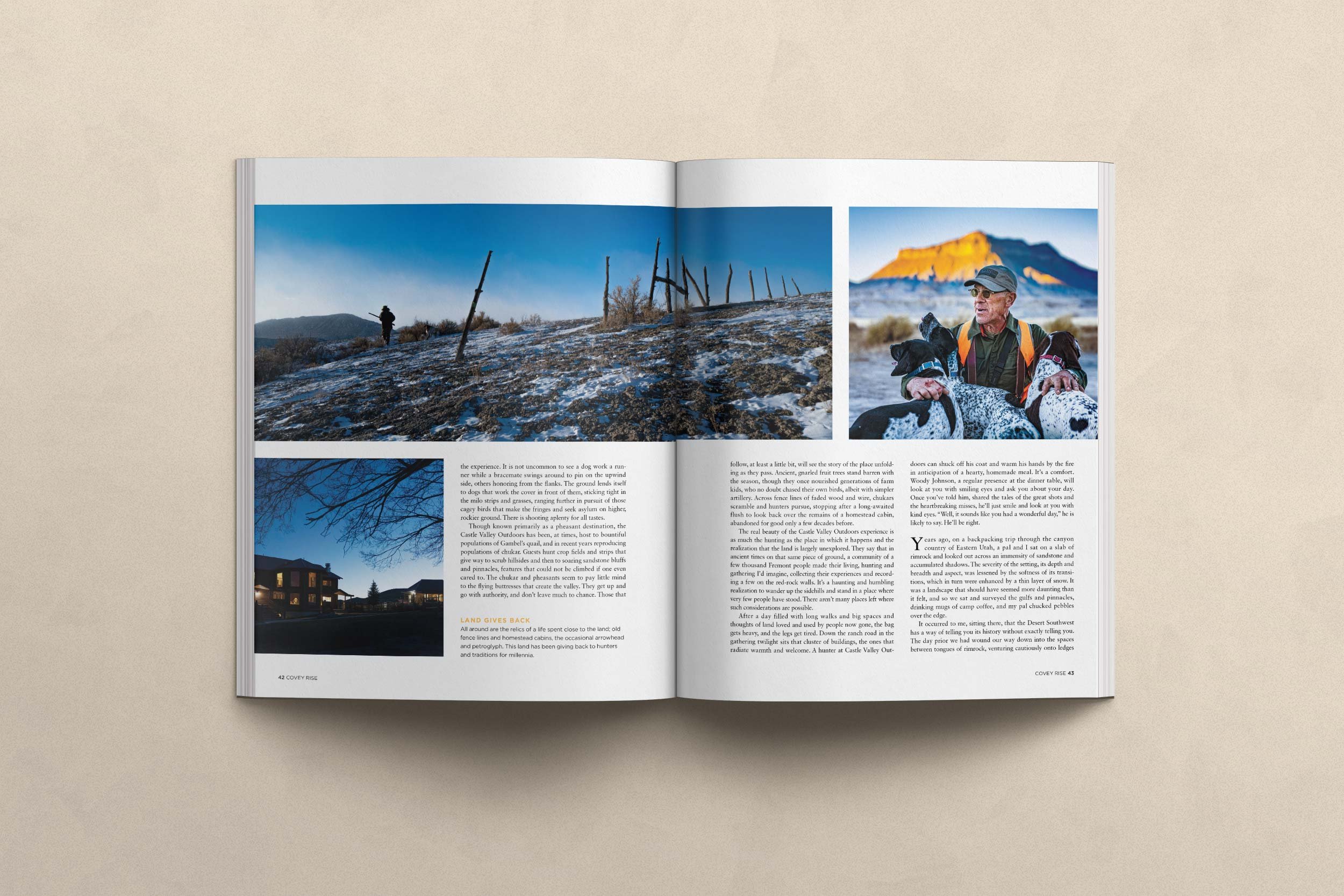

After a day filled with long walks and big spaces and thoughts of land loved and used by people now gone, the bag gets heavy and the legs get tired. Down the ranch road in the gathering twilight sits that cluster of buildings, the ones that radiate warmth and welcome. A hunter at Castle Valley Outdoors can shuck off his coat and warm his hands by the fire in anticipation of a hearty, homemade meal. It’s a comfort. Woody Johnson, a regular presence at the dinner table, will look at you with smiling eyes, and ask you about your day. Once you’ve told him, shared the tales of the great shots and the heartbreaking misses, he’ll just smile and look at you with kind eyes. “Well it sounds like you had a wonderful day,” he is likely to say. He’ll be right.

*

Years ago, on a backpacking trip through the canyon country of eastern Utah, a pal and I sat on a slab of rimrock and looked out across an immensity of sandstone and accumulated shadows. The severity of the setting, its depth and breadth and aspect, was lessened by the softness of its transitions, which in turn were enhanced by a thin layer of snow. It was a landscape that should have seemed more daunting than it felt, and so we sat and surveyed the gulfs and pinnacles, drinking mugs of camp coffee, and my pal chucked pebbles over the edge.

It occurred to me, sitting there, that the desert southwest has a way of telling you its history without exactly telling you. The day prior we had wound our way down into the spaces between tongues of rimrock, venturing cautiously onto ledges and ducking beneath overhangs. Our descent was measured by striations in the rock, physical contours we grasped in our hands for balance. These were etchings made during the uplift of the Colorado Plateau, when the earth was taking its magnificent shape, and an epoch filled with rushing water slowly, but unrelentingly, carved the landscape. In a spot seemingly overlooked for a thousand years, we’d found the remains of an Anasazi living site: pot shards and chips of worked stone littered the ground, and tucked in the crevices were desiccated corn cobs. We touched these things gently, looked them over, and backed our way off the ledge to continue down. We spent the remains of the day wandering around on the canyon floor, realizing only in the moonlight that the way up and out was far more problematic than the way down in.

As we sat drinking coffee and considering the day, I felt somehow connected to a story still being told, one whose previous chapters were laid out all around me, stretching back to the beginnings of time. The hand-hewn logs of homestead cabins, the fractured arrowheads, the atomic movement of the earth’s crust... it was all right there, illuminated in sunlight that was warming it all and melting away the snow. It was a big and vacuous feeling for a boy to have in a big and vacuous place. I never forgot it. I suppose in some way its why I have returned to Utah again through my adulthood, to be warmed by its sun, to play a bit part in the story it shares so readily.

Castle Valley Outdoors affords a similar experience, and that in itself is a gift. It revolves around the bird hunting for sure, but somehow at the heart of the experience is a narrative, a priority, that is more timeless, and the hunt becomes the vehicle by which you come to notice it. Castle Valley Outdoors is about Utah, and the American West, and the legacy of folks who eeked a living out of it, and also managed to thrive. It is about a tradition of people who wander through magnificent places, who stop long enough to look around and see the beauty rising, illuminating the details big and small. It is about the process of appreciating the simplest things: a pointing dog locked up and three more honoring, a dusting of snow that melts with the sun, a sturdy gate that does its job and welcomes those who appreciate the good work done beyond. All of these become priorities that persist, priorities embodied by the Johnson family and Jim Fauver, and easily adopted by Castle Valley friends and guests.

At Castle Valley Outdoors its quite easy to keep your priorities straight.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine