The Triumph of an Empty Freezer

When we were kids, my older sister had the irritating habit of stretching her haul of Halloween candy well beyond the bounds of November, and sometimes as far as Christmas. Her restraint was remarkable; all these years later I still recall watching as she painstakingly unwrapped a Reese’s Peanut-Butter Cup, took a measured nibble, and then re-wrapped what was left for consideration some days later. As a rule, she performed this charade only in my presence, and I suppose that her delight in protracting that seasonal wealth was made all the sweeter by my inability to make my candy last longer than a few days. The autumns of my youth were all slavering anticipation followed by a cascade of gluttony, after which candy wrappers and a bellyache were the sole vestiges of October’s riches. That my sister on occasion hoarded her candy so long that it got stale and chucked in the trash was, despite the obvious philosophic implications, of little consolation to me.

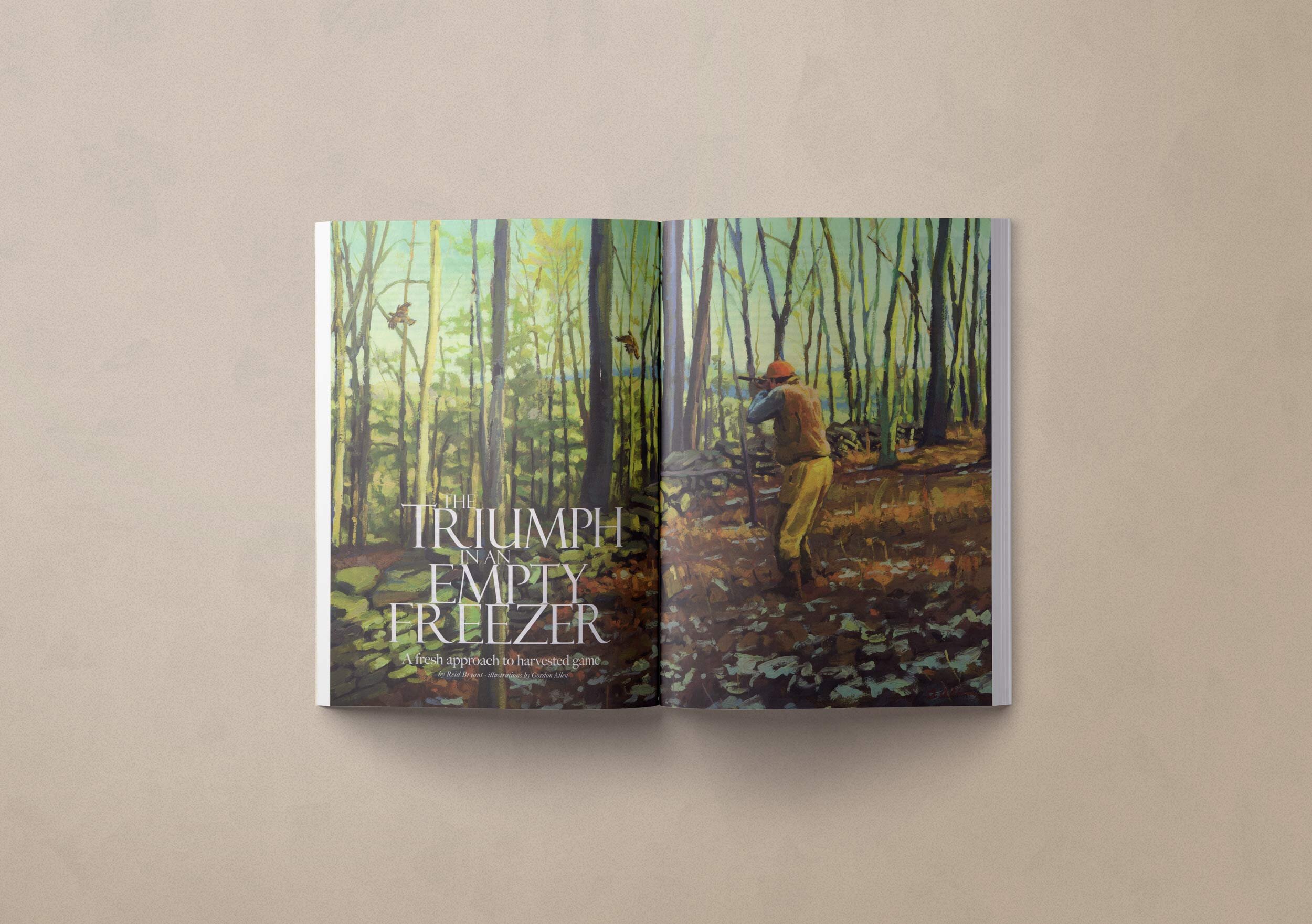

Perhaps it was a sort of sibling rivalry that led to my inevitable aspiration towards a reserve more like my sister’s. With the passage of childhood and the arrival of youth I gained a degree of self-discipline which translated, later in life, from Halloween candy to matters more befitting of a man. I like to think that by middle-adulthood I’d achieved a tight-fisted, and somewhat puritan, command of my compulsions, gastronomically anyway. Granted, my tastes have changed a bit: what October currency I once measured in Hershey Bars and Tootsie Pops, I now find in the bits of flesh and feather that I tease from the alder runs and popples, at least those that fall occasionally to my well-timed shots. These are prizes that I carefully draw and quarter, and stack like bound bills in my freezer. Truth be told, the boy in me sometimes looks down into the freezer with a fluttering rashness, one that knows the highest tribute afforded a piece of game is to save it from the deep freeze altogether. I know, by experience and by anecdote, that a grouse or a woodcock is best dealt a few days in the woodshed, followed by a plucking, a searing, and and a delivery to the plate hot and rare. But then, the agonies of youth leave a bitter taste, as do the fears of scarcity, so I pack and freeze my game, and savor instead the steady filling of the ice box.

On a recent late-summer Sunday, I found myself elbow-deep in the cellar freezer chest, rifling through the remains of last season’s meat in want of a little something for the grill. I knew that there were some dove breasts down there, and, I thought anyway, a few packages of spatchcocked blue quail from the West Texas brush country. As I dug through the scattered bags and paper-wrapped parcels, I took some pride in the riches that remained in my coffers; after all, a good haul of game by summer’s end was proof of my parsimony, and the fact that I’d perhaps outgrown the intemperance of my youth. And then, from the far bottom corner I plucked an ice-crusted zip lock bag of dubious origin, un-labeled save for a scrawled 2014 in black marker. Inside, I was appalled to find the freezer-burned remains of three woodcock, a day’s limit sadly forgotten, no doubt at the time squirreled away in reverie, an homage to my skill. That I couldn’t remember the day or the birds saddened me all the more, for the memories I’d intended to freeze in time and plastic had, like the birds themselves, been forgotten as the seasons slipped by.

I stood there in my basement, looking down into a perceived wealth of frozen game stacked like drying sod blocks, or bars of gold. There was a wealth of food in there for certain, but so too an almanac of days, a catalog of successes and shots that met their mark, moments spent in tailgate admiration. In the meat and gristle I’d planned to eat there was intention at rest, one in which those moments and memories, those slivers of the wild, would become a part of me. My mislaid plan had been to portion this nourishment out into an uncertain future, and to know that I was rich. But in my hands I held that wealth gone stale and meaningless, to be thrown away like my sister’s candy all those years before.

I looked down into the freezer and scanned the packages, each one neatly labeled in black ink. Drake Mallard, Maggie’s Pond – 2017 was the remainder of a morning wherein a lonesome greenhead fell victim to my calls, and snaked his way in through the cattail maze to rise like a phoenix before my gun. 3 Sharptails Stanford -2017 was a pound or two of the best day Josiah and Ronnie and I ever saw on the Montana prairie, and a mere fraction of the covey rises that numbered so many we didn’t dare tell, in case we’d have been thought to be liars. There was a backstrap from Kim’s first deer, a heavy doe that slunk right up the field edge on a December afternoon, teaching my wife that joy and sadness can seep together out of the heart and into the frozen ground. And there was of course the grouse I’d shot with Keith in Minnesota, not knowing that my friend would be dead within the year, and my moments with him would be frozen alongside the carcass of a bird I’d been so proud to see falling out of the pinetops. But the three woodcock, and the day in which we’d collided, were lost to the years and the freezer burn.

The older I get, the more often I wonder if there isn’t something quite lovely, quite reverent, in the raw and unabashed enthusiasm of youth. I wonder if in planning for the lean times, in amassing our wealth only to monitor it and fear its loss, we don’t just keep our joys more distant, and harder to remember. And I wonder too if the memory of a thing requires something so tangible, something that loses its heat and its nuance as the cells of it crystallize, and inevitably fracture, while the ink that memorializes it fades. It has been a long time since I dumped a pile of candy on the floor and raked through it like a she-bear, emerging some time later with chocolate on my face. I’d be embarrassed to be caught at such a thing these days, even if I were so inclined. But so too has it been awhile since I ate all the season’s grouse fresh and plucked, or celebrated the teal opener with a hot fire and cold beer, wrapping the diminutive birds in bacon and jalapeno in plain sight of the water whence they were taken. Maybe it’s time I did so. Maybe it’s time I took heart that the moments will keep coming, and that their memories need not be locked away, or memorialized, but rather relished as they come. Maybe it’s time I learned to see the triumph in an empty freezer, and a season well-spent and well-savored, every step of the way.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine