Portrait of an Artist

“To discover the mode of life or of art whereby my spirit could express itself in unfettered freedom.”

Some time ago, I spent an afternoon with a shooting instructor who quickly identified a failing in me that I too had long suspected. “You, my friend,” he’d said, “are lazy.”

I was taken aback by his frankness, and his discernment.

“But I just broke five targets running,” I said, the air hissing out of my ego. “I haven’t shot this well in a while…”

My instructor shook his head, disgusted that I’d managed to miss his point. “Breaking the target, or taking a chip, or being ‘close enough’ is not what we are after. A great shooter sees the target with such clarity, and executes the shot with such precision, that the game becomes a matter of where and how it breaks, not that it breaks. You are lazy because you are not willing to concentrate on really seeing what you are looking at, and you refuse to hold yourself to the finer details of your intention. Now, try again…”

I missed the next four targets, pulled a chip off the arse-end of the fifth, and walked away wondering if I’d just had a lesson in wingshooting or the meanderings of the Tao.

*

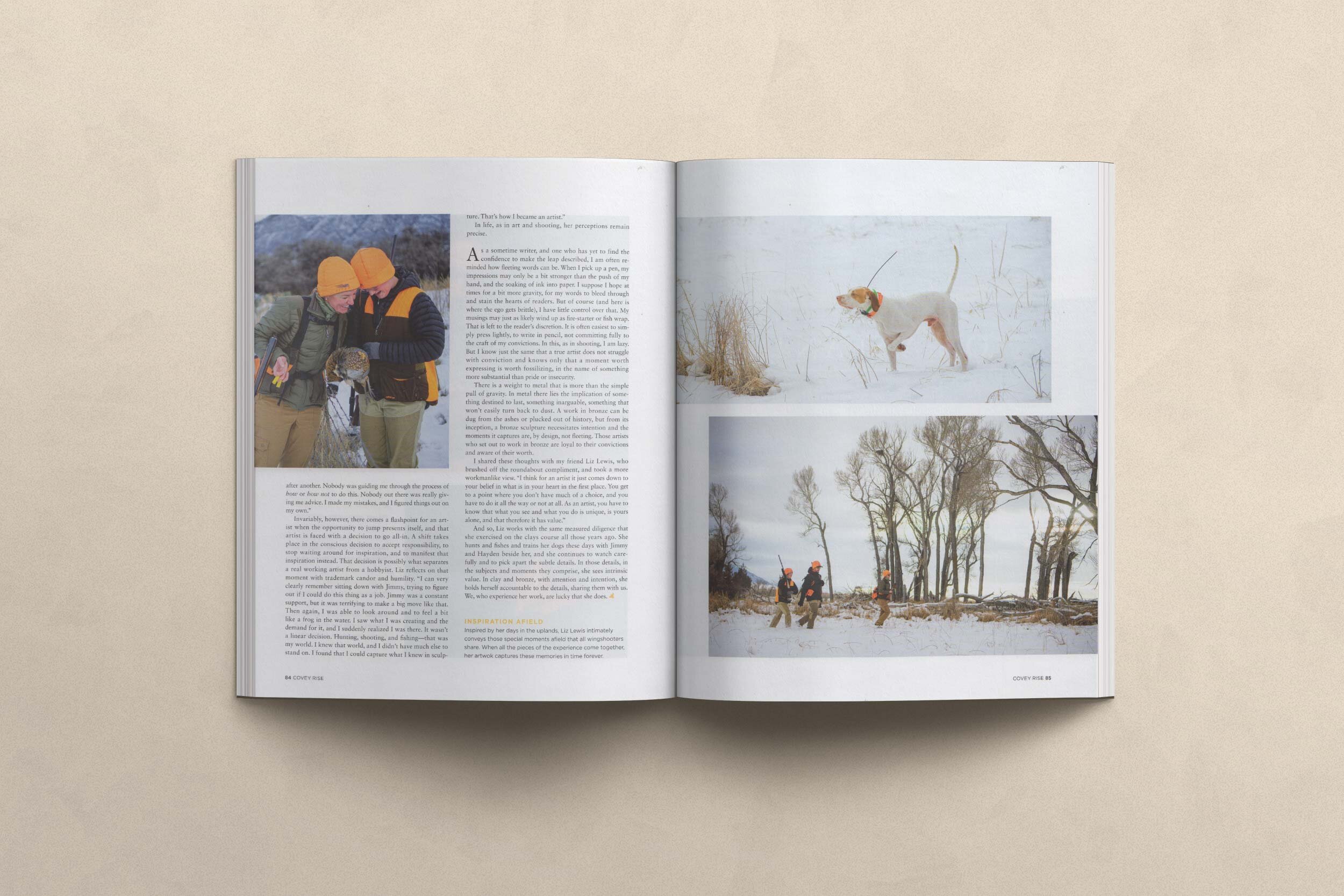

Great shooters share this habit of seeing precisely, of dialing subtlety into focus. It is a habit that seems to permeate other pieces of their lives too, their relationships and their expressions, or simply their observations of moments unfolding. You’ll find that great shooters, like my instructor, notice the forest with acuity and ease, then they lean right past the trees to examine the margins of each leaf, and cast of each shadow, the dust motes dancing through the branches. And sometimes, when a great shooter turns that attention to expressive art, he or she creates work of vivid detail, of abject honesty. Such is the work of sculptor Liz Lewis.

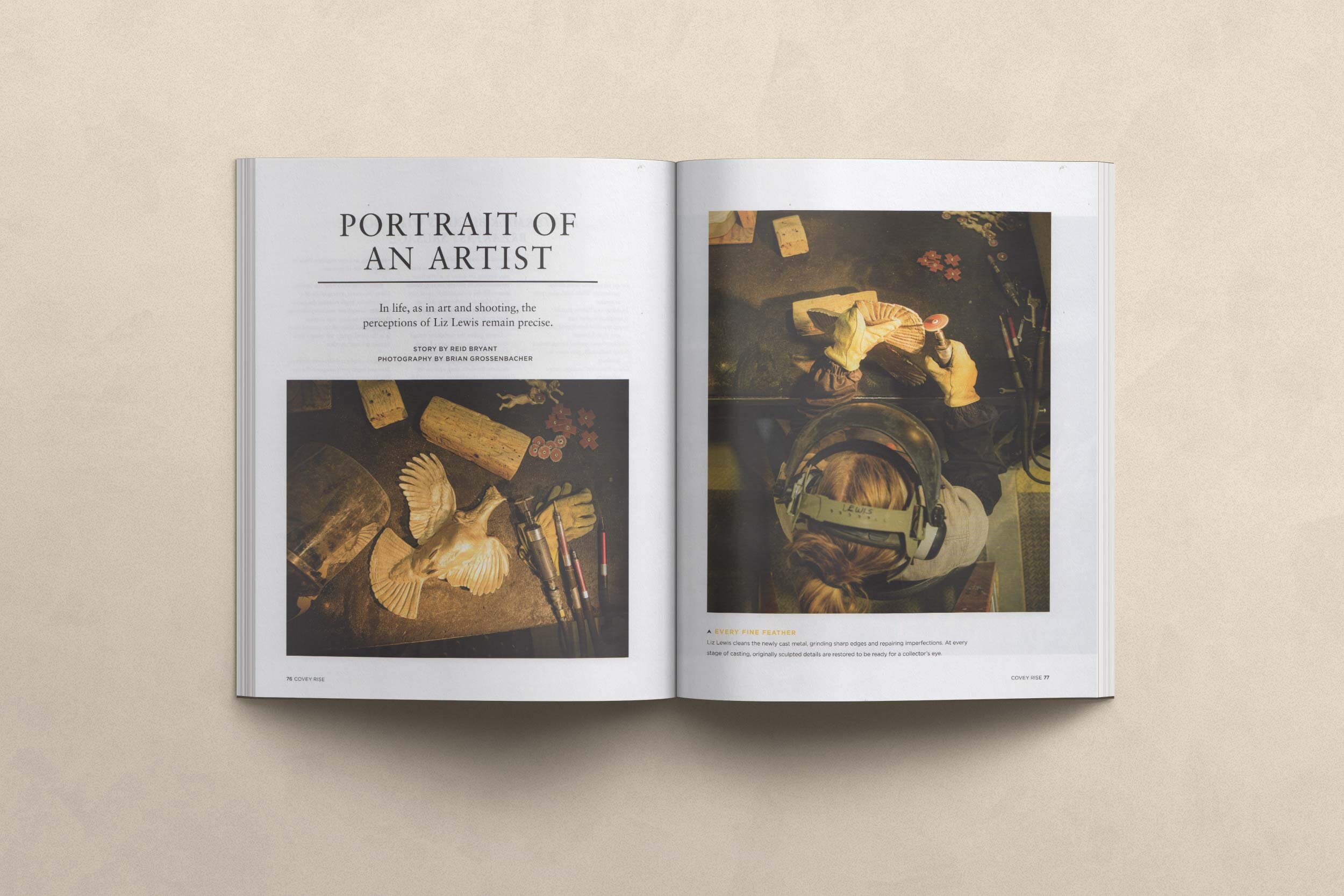

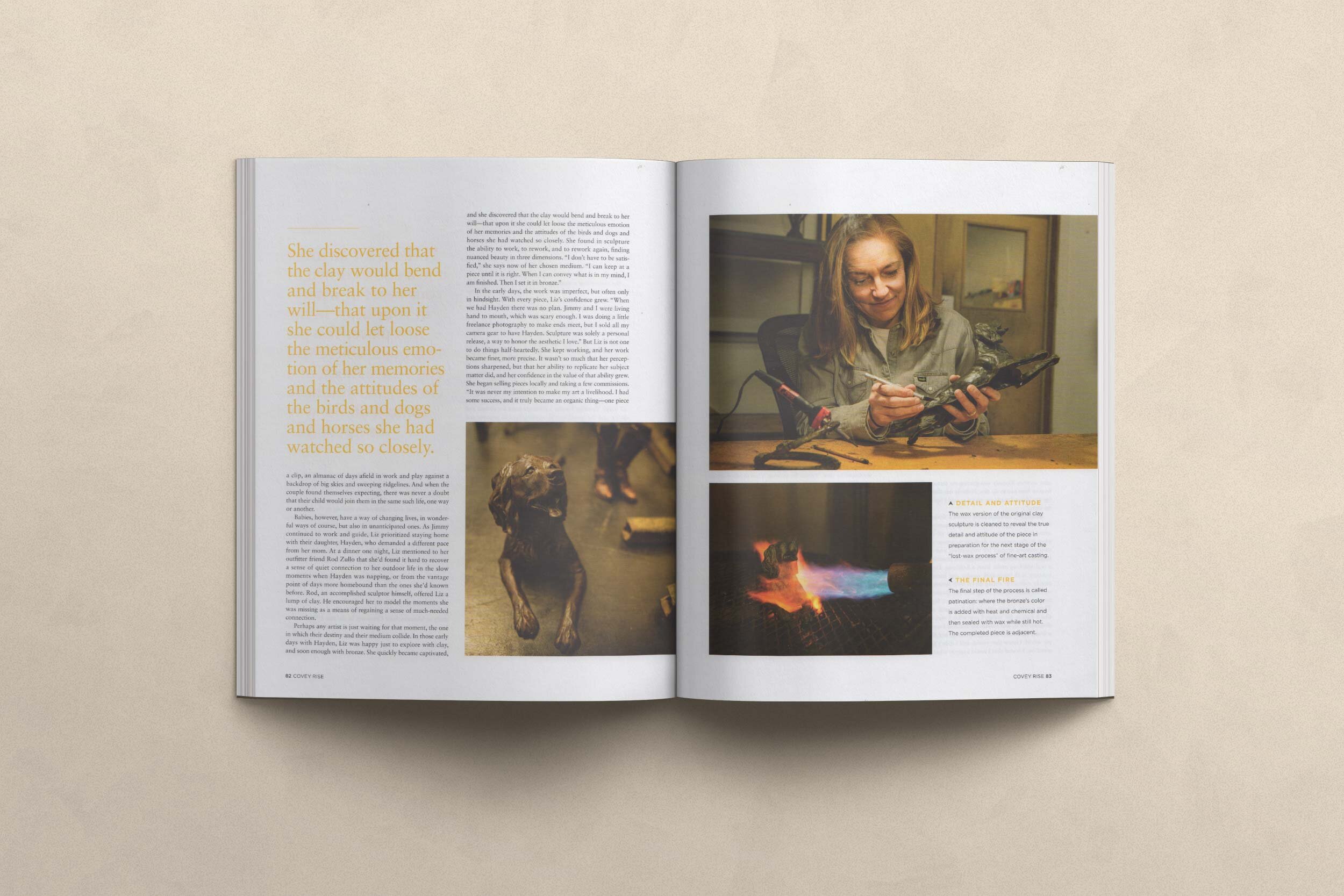

On a wintry day, Liz sits in her studio in Bozeman, Montana, fashioning a Boykin Spaniel out of clay. The inspiration for her work is splayed on the floor at Liz’s feet, chasing pheasants through a dreamscape of cattails and hoarfrost. Liz has built an armature of wire and bent metal to serve as a rough skeleton of the dog, and upon this armature she smears clay upon layer of clay, invoking muscle and flesh, anticipation and whimsy. The stereo is on, and Liz is intent upon all that is taking shape beneath her fingertips; this process, this equation of building up and removing the unnecessary, will go on as long as it must. At some point in the future, hours or weeks from now, Liz will look down at the piece in her hands and see what she saw in her mind’s eye, and she will know that the piece is done. She will sign it, lift it carefully from the table, and bring it to the foundry in town. There, its negative will be duplicated in rubber, which will in turn be filled with wax, around which in turn yet another mold will be formed in heat-tolerant silica. At every step, Liz will run her hands over the minutiae of knee joints and ear hairs, of a head tilted slightly back, making sure each detail retains the integrity she afforded it. Then that final mold will be filled with molten bronze, and Liz’s impression of a dog sprawled out and intent will be suspended forever. Despite the static permanence of metal, it will remain somehow alive.

But Liz isn’t considering that uncertain future right now; she’s bent over her table, frowning just a little; her dark eyes are shining, and a tendril of red hair has escaped her ponytail, and it hangs in front of her eyes. She’s building up a memory, letting a life’s worth of practice seeing details guide her fingers as she coaxes a canine smile, a wriggling stub of tail, out of a lump of earth.

It’s hard to say if Liz was an artist first, or a shooter, and perhaps it doesn’t matter. An artist, like a shooter, is asked to look hard, to watch closely, and to hold herself accountable to detail. A good one sees nuance in the attitude of a thing, the way motion dissipates into stasis, the way an upper lip hangs on a crooked tooth. An artist is blessed with the ability to work patiently in her medium until those details are harnessed. Liz Lewis, who has established herself on a world stage as both an artist and a shooter, is matter-of-fact about the precision of her perception, and her dogged commitment to capturing it. “I work hard to get enough control over my medium to express more than the snapshot, to translate things you can’t even see with the naked eye. I want to be able to convey the beauty of the situation, the true essence of the animal or the moment. In the end, I can’t be satisfied until I offer a scene the justice it is due.”

But controlling a medium, and even simply seeing well, did not always come easy. Liz was a little girl in Illinois when she was diagnosed with a visual disturbance, one that resulted in double-vision throughout the major range of her sight. This anomaly made it hard for Liz to follow a line of music, or play in ball games, or learn to read. Perhaps this trouble seeing made Liz regard the world more emphatically, required her to look harder in order to grab hold of the specifics lest they splinter off into the blurry fringes. Some solace was to be found serendipitously on the rifle range. When she was still a very small girl, Liz’s father, a passionate hunter and shooter, introduced her to the .22, and in shooting Liz was able to force those shimmering images into focus. She found that over a gun barrel she could suspend an image long enough to grasp its details, and long enough to pin them in place with a .22 bullet. Shooting became a reference point for success and clarity, and she leaned into it, working hard to improve, and to see her target better.

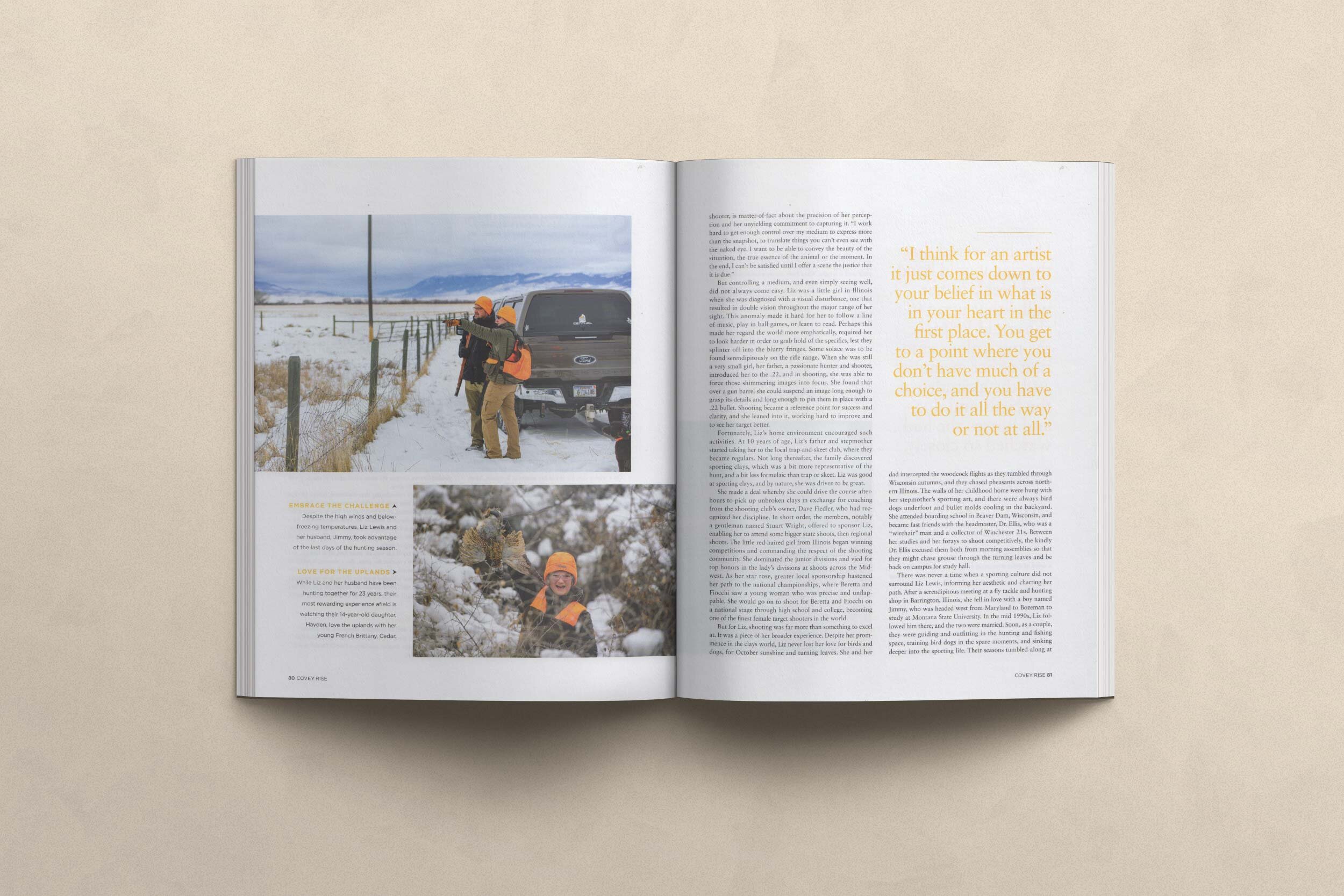

Fortunately, Liz’s home environment encouraged such activities: at 10 years of age, Liz’s father and stepmother started taking her to the local trap and skeet club, where they became Thursday night regulars. Not long thereafter, the family discovered sporting clays, which was a bit more representative of the hunt, and a bit less formulaic than trap or skeet. Liz was good at sporting clays, and by nature driven to be great; she made a deal whereby she could drive the course after-hours picking up unbroken clays in exchange for coaching from the shooting Club’s owner Dave Fiedler, who had recognized her discipline. In short order, the Club members, notably a gentleman named Stuart Wright, offered to sponsor Liz, enabling her to attend some bigger state shoots, then regional shoots. The little red-haired girl from Illinois began winning competitions and commanding the respect of the shooting community; she dominated the junior divisions and vied for top honors in the lady’s divisions at shoots across the Midwest. As her star rose, greater local sponsorship hastened her path to the National Championships, where Beretta and Fiocchi saw a young woman who was precise and unflappable. Liz would go on to shoot for Beretta and Fiocchi on a national stage through high school and college, becoming one of the finest female target shooters in the world.

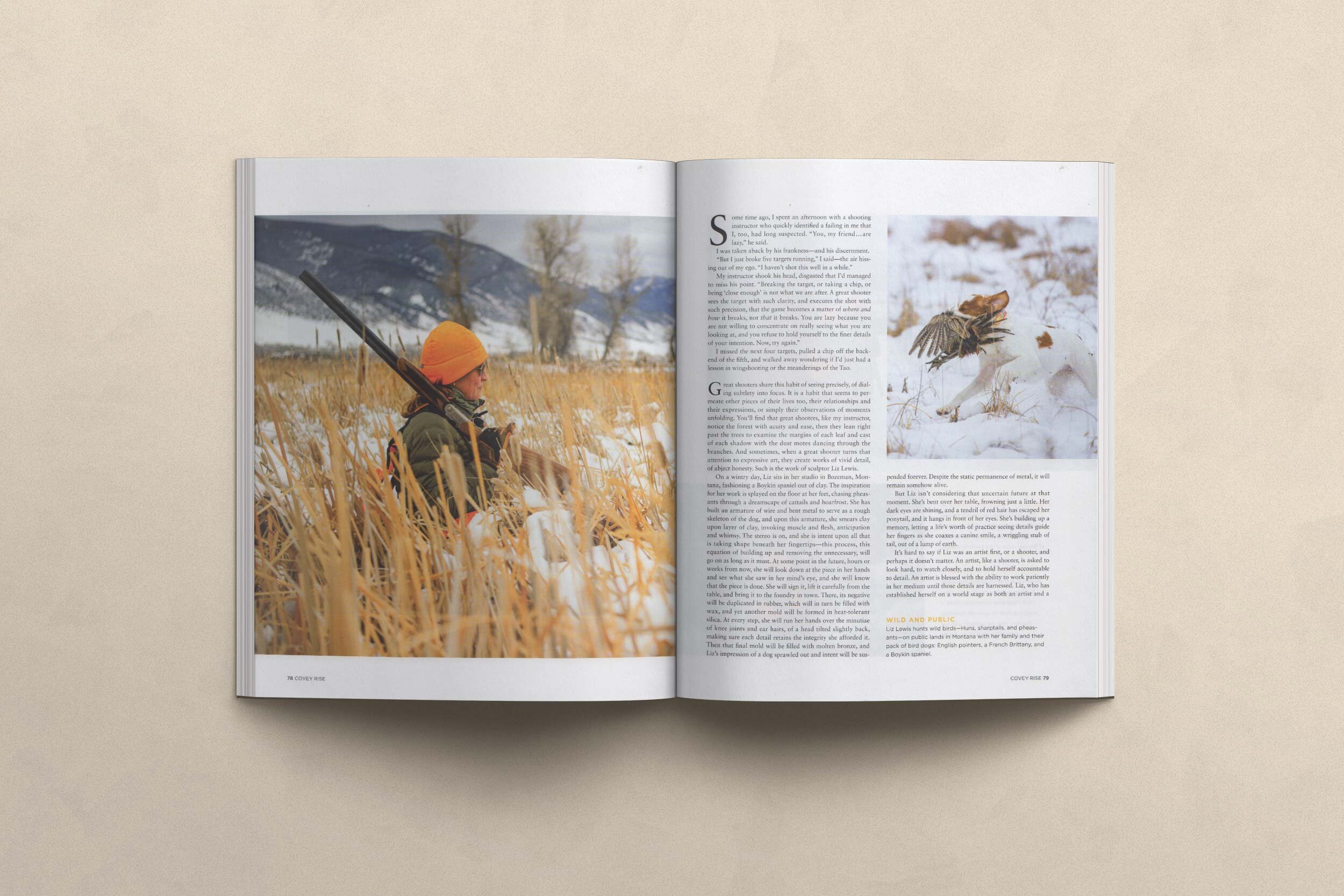

But for Liz Lewis, shooting was far more than something to excel at; it was a piece of her broader experience. Despite her prominence in the clays world, Liz Lewis never lost her love for birds and dogs, for October sunshine and turning leaves. She and her dad intercepted the woodcock flights as they tumbled through Wisconsin autumns, and they chased pheasants across northern Illinois. The walls of Liz’s childhood home were hung with her stepmother’s sporting art, and there were always bird dogs underfoot, and bullet molds cooling in the backyard. Liz attended boarding school in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, and became fast friends with the Headmaster Dr. Ellis who was a Wirehair man, and a collector of Winchester 21’s. Betwixt and between Liz’s studies and her forays to shoot competitively, the kindly Dr. Ellis excused them both from morning assemblies so that they might chase grouse through the turning leaves, and be back on campus for study hall. There was never a time when a sporting culture did not surround Liz Lewis, informing her aesthetic, and charting her path. After a serendipitous meeting at a fly tackle and hunting shop in Barrington, Illinois, Liz fell in love with a boy named Jimmy, who was headed west from Maryland to Bozeman to study at MSU. In the mid 1990’s, Liz followed him there, and the two were married. Soon, as a couple, they were guiding and outfitting in the hunting and fishing space, training bird dogs in the spare moments, sinking deeper into the sporting life. Their seasons tumbled along at a clip, an almanac of days afield in work and play against a backdrop of big skies and sweeping ridgelines. And when the couple found themselves expecting, there was never a doubt that their child would join them in the same such life, one way or another.

Babies, however, have a way of changing lives, in wonderful ways of course, but also in unanticipated ones. As Jimmy continued to work and guide, Liz prioritized staying home with their daughter Hayden, who demanded a different pace from her mum. At a dinner one night, Liz mentioned to her outfitter friend Rod Zullo that she’d found it hard to recover a sense of quiet connection to her outdoor life in the slow moments when Hayden was napping, or from the vantage point of days more home-bound than the ones she’d known before. Rod, an accomplished sculptor himself, offered Liz a lump of clay. He encouraged her to model the moments she was missing as a means of regaining a sense of much-needed connection.

Perhaps any artist is just waiting for that moment, the one in which their destiny and their medium collide. In those early days with Hayden, Liz was happy just to explore with clay, and soon enough with bronze. She quickly became captivated, and she discovered that the clay would bend and break to her will, and that upon it she could let loose the meticulous emotion of her memories, and the attitudes of the birds and dogs and horses she had watched so closely. She found in sculpture the ability to work, to re-work, and to re-work again, finding nuanced beauty in three dimensions, set free by the clay to build up and remove until the necessary tension or the lassitude was perfect. “I don’t have to be satisfied,” she says now of her chosen medium. “I can keep at a piece until it is right. When I can convey what is in my mind, I am finished. Then I set it in bronze.”

In the early days, the work was imperfect, but often only in hindsight. With every piece, Liz’s confidence grew. “When we had Hayden there was no plan. Jimmy and I were living hand-to-mouth, which was scary enough. I was doing a little freelance photography to make ends meet, but I sold all my camera gear to have Hayden. Sculpture was solely a personal release, a way to honor the aesthetic I love.” But Liz Lewis is not one to do things half-heartedly. She kept working, and her work became finer, more precise. It wasn’t so much that her perceptions sharpened, but that her ability to replicate them did, and her confidence in the value of that ability. She began selling pieces locally and taking a few commissions. “It was never my intention to make my art a livelihood. I had some success, and it truly became an organic thing… one piece after another. Nobody was guiding through the process of how or how not to do this; nobody out there was really giving me advice. I made my mistakes, and I figured things out on my own.”

Invariably, however, there comes a flashpoint for an artist when the opportunity to jump presents itself, and that artist is faced with a decision to go all-in. A shift takes place in the conscious decision to accept responsibility, to stop waiting around for inspiration, and to manifest that inspiration instead. That decision is possibly what separates a real working artist from a hobbyist. Liz reflects on that moment with trademark candor and humility. “I can very clearly remember sitting down with Jimmy, trying to figure out if I could do this thing as a job. Jimmy was a constant support, but it was terrifying to make a big move like that. Then again, I was able to look around, and to feel a bit like a frog in the water; I saw what I was creating, and the demand for it, and I suddenly realized I was there. It wasn’t a linear decision. Hunting, shooting, and fishing… that was my world. I knew that world and I didn’t have much else to stand on, and I found that I could capture what I knew in sculpture. That’s how I became an artist.”

In life, as in art and shooting, her perceptions remain precise.

*

As a sometime writer, and one who has yet to find the confidence to make the leap described, I am often reminded how fleeting words can be. When I pick up a pen, my impressions may only be a bit stronger than the push of my hand, and the soaking of ink into paper. I suppose I hope at times for a bit more gravity, for my words to bleed through and stain the hearts of readers. But of course, (and here is where the ego gets brittle), I have little control over that. My musings may just as likely wind up as fire-starter or fish-wrap… that is left to the reader’s discretion. It is often easiest to simply press lightly, and to write in pencil, not committing fully to the craft of my convictions. In this, as in shooting, I am lazy. But I know just the same that a true artist does not struggle with conviction and knows only that a moment worth expressing is worth fossilizing, in the name of something more substantial than pride or insecurity.

There is a weight to metal that is more than the simple pull of gravity. In metal there lies the implication of something destined to last, something inarguable, something that won’t easily turn back to dust. A work in bronze can be dug from the ashes or plucked out of history, but from its inception, a bronze sculpture necessitates intention and the moments it captures are, by design, not fleeting. Those artists who set out to work in bronze are loyal to their convictions, and aware of their worth.

I shared these thoughts with my friend Liz Lewis, who brushed off the roundabout compliment, and took a more workmanlike view. “I think for an artist it just comes down to your belief in what is in your heart in the first place. You get to a point where you don’t have much of a choice, and you have to do it all the way or not at all. As an artist, you have to know that what you see and what you do is unique, is yours alone, and that therefore it has value.”

And so, Liz Lewis works with the same measured diligence that she exercised on the clays course, all those years ago. She hunts and fishes and trains her dogs, these days with Jimmy and Hayden beside her, and she continues to watch carefully, and to pick apart the subtle details. In those details, in the subjects and moments they comprise, she sees intrinsic value. In clay and bronze, with attention and intention, she holds herself accountable to the details, sharing them with us.

We, who experience her work, are lucky that she does.

First published in Covey Rise August/September 2020