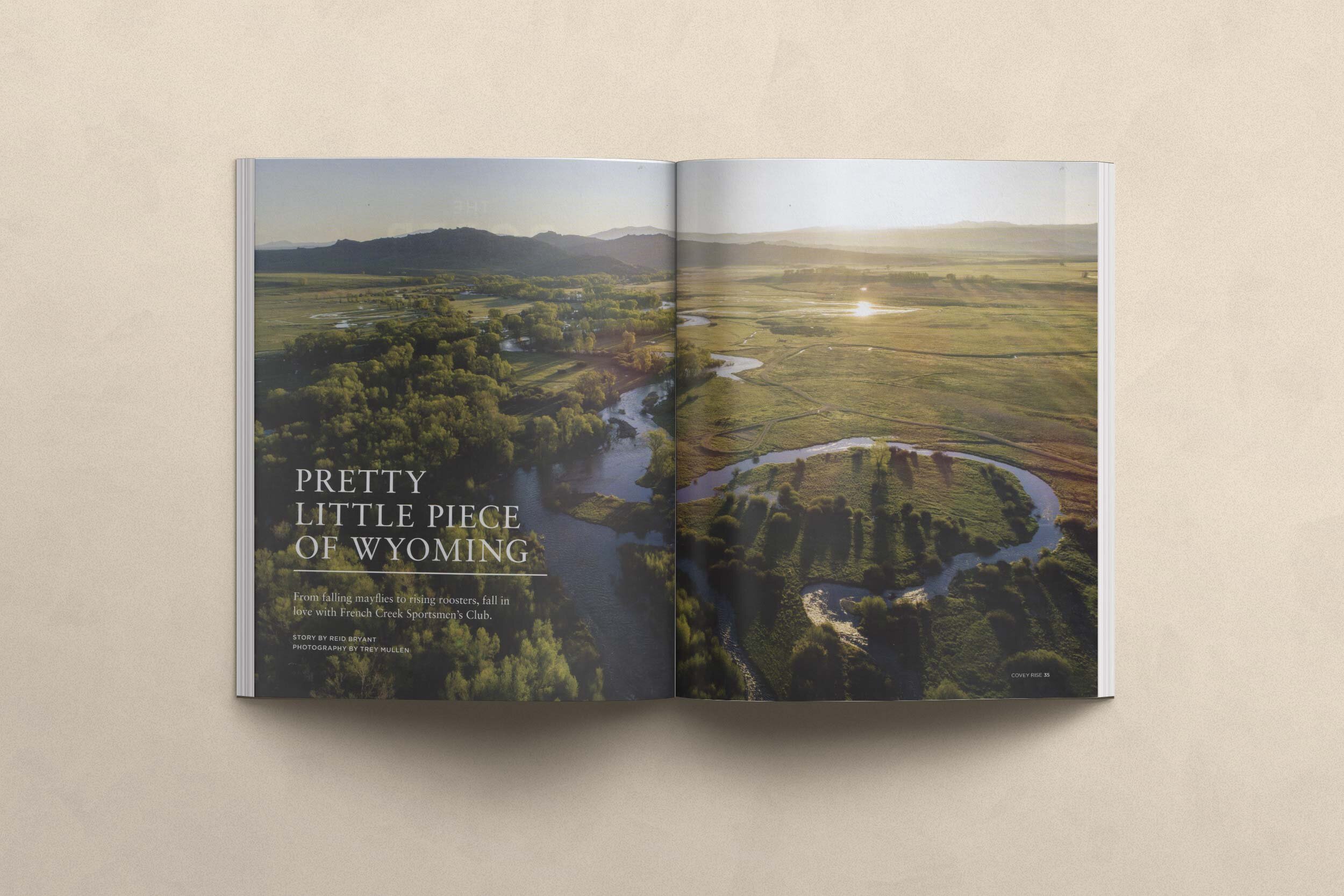

Pretty Little Piece of Wyoming

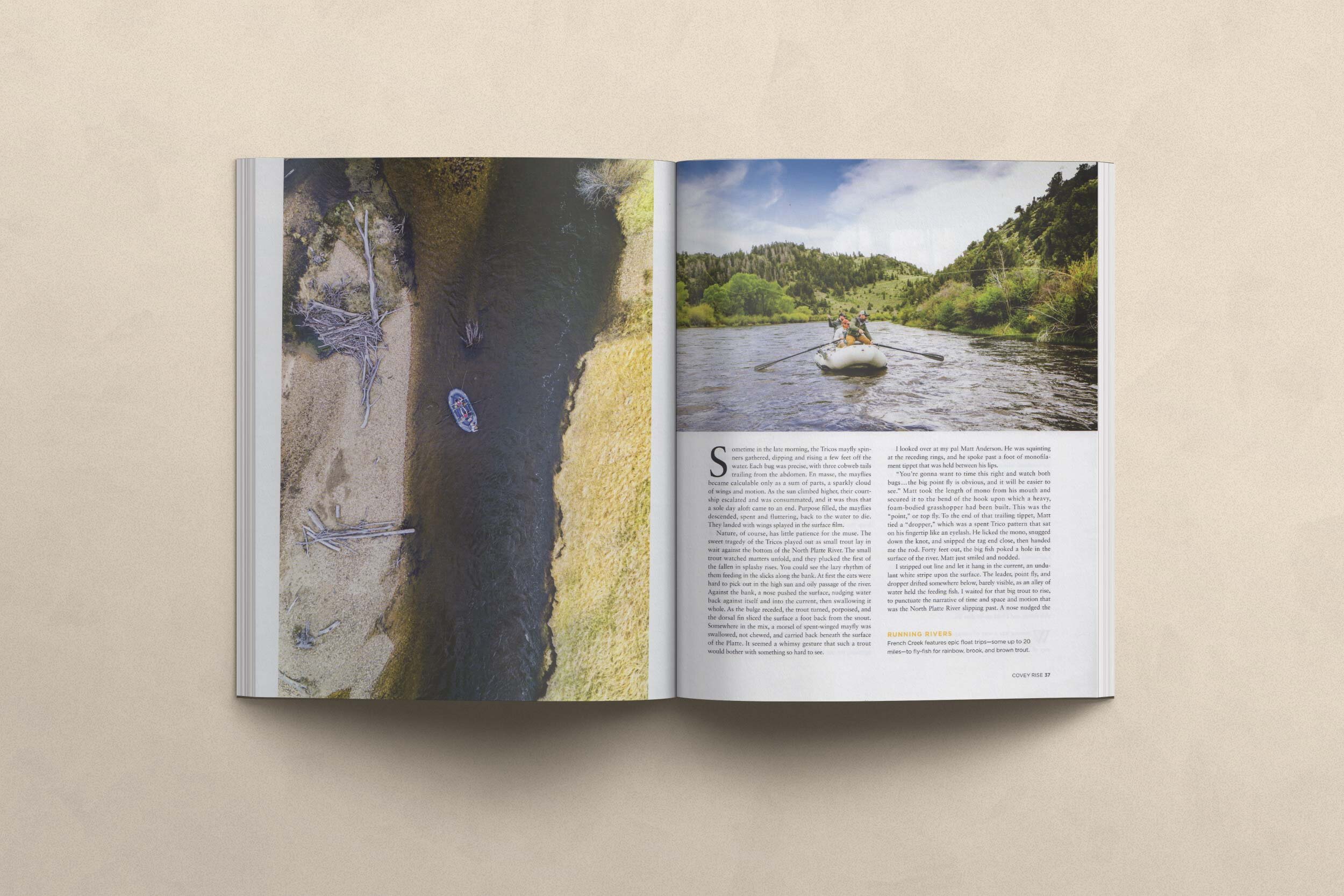

NSometime in the late morning the Tricorythodes mayfly spinners gathered, dipping and rising a few feet off the water. Each bug was precise, with three cobweb tails trailing from the abdomen. En masse the mayflies became calculable only as a sum of parts, a sparkly cloud of wings and motion. As the sun climbed higher, their courtship escalated and was consummated, and it was thus that a sole day aloft came to an end. Purpose filled, the mayflies descended, spent and fluttering, back to the water to die. They landed with wings splayed in the surface film.

Nature, of course, has little patience for the muse. The sweet tragedy of the Tricos played out as small trout lay in wait against the bottom of the North Platte River. The small trout watched matters unfold, and they plucked the first of the fallen in splashy rises. As the Tricos began to fall in earnest, the bigger trout lumbered up from the dark water and shouldered the littler fish aside. You could see the lazy rhythm of them feeding in the slicks along the bank. At first the eats were hard to pick out in the high sun and oily passage of the river. As we moved in closer, though, the dimples became more substantial: against the bank, a nose pushed the surface, nudging water back against itself and into the current, then swallowing it whole. As the bulge receded, the trout turned, porpoised, the dorsal slicing the surface a foot back from the snout. Somewhere in the mix, a morsel of spent-winged mayfly was swallowed not chewed, and carried back beneath the surface of the Platte. It seemed a gesture of whimsy that such a trout would bother with something so hard to see.

I looked over at my pal Matt Anderson. He was squinting at the receding rings, and he spoke past a foot of monofilament tippet that was held between his lips.

“You’re gonna want to time this right and watch both bugs… the big point fly is obvious, and it will be easier to see.” Matt took the length of mono from his mouth and secured it to the bend of the hook upon which a heavy, foam-bodied grasshopper had been built. This was the “point” or top fly. To the end of that trailing tippet Matt tied a “dropper”, a spent Trico pattern that sat on his fingertip like an eyelash. He licked the mono and snugged down the knot and snipped the tag end close, handing me the rod. Forty feet out, the big fish poked a hole in the surface of the river. Matt just smiled and nodded.

I stripped out line and let it hang in the current, an undulant white stripe upon the surface. The leader and point fly and dropper drifted somewhere below, barely visible, as an alley of water was pocked by feeding fish. I waited for that big trout to rise, to punctuate the narrative of time and space and motion that was the North Platte River slipping past. A nose nudged the surface as an unquantifiable number of dead and dying mayflies skated past my legs. I lifted the line, offered some length to the overhead false cast, and pushed the rod forward, letting go with my left hand. The fly line and tippet unfurled straight to the hopper, and the dropper laid out behind, a whisper and a wink of light on monofilament.

“That’s the lane…” said Matt as the littler fly, somewhere behind the bigger fly, slid past us unseen. It was forty feet out at right angles to the current, easing into the big trout’s vision.

“Watch the hopper…” Matt stopped breathing for a second.

A big trout makes decisions quickly, but without haste. In a river in southern Wyoming, in the primitive mind of a trout, something of value appeared all at once, framed against a sage-tinted sky. In fractions of a moment it tugged a heavy fish up through refracted light and cold, shimmering water, and asked of him conviction. The fish, fully convinced, set out to tug it right back down.

Forty feet out, the water downstream of the point fly opened up, a beaky mouth gaped and shut, and Matt shouted “SET!” as the world became electric and alive.

Line sliced water as a big trout became aware of humans’ comfortable deceit, and I held on for dear life.

*

Wyoming has a way of juxtaposing its glorious details against something broad, bleak, and windblown. It has a way of deconstructing scale. It is in the landscape, in the way that each shadowy cleft in the sagebrush disappears into a sea of the same. That said, Wyoming at points reveals significance tucked among the wrinkles. As I dropped out of the forested ridges of the Snowy Range and into the scrubland around Saratoga, I braked as three cow elk and a yearling tumbled out of the timber. My heart beat hard and I watched them disappear, then looked beyond where they had been to the broad stroke of ground unfolding ahead. It was so seemingly endless I could not fathom how long it might take me to meet the horizon. I felt, as I always feel in such places, that the sage country was indifferent to my presence, perhaps too big or rawhide tough to care if I entered or left it.

I dropped out of the timber of the Snowy Range and lost elevation, turning off the tar road onto gravel. It was early September, and a last late cut of hay was coming off the Platte bottomlands. I could see the flatbeds coming from a half-mile out, the dust rising from the loose road. As the distances between me and the dust closed, I steered to the shoulder, letting the trucks pass at speed, letting the billows swallow me up as the timber had swallowed the elk. When I managed to re-emerge, the world appeared barely defined even in high sun. I wandered through that veiled space until I saw Matt Anderson’s truck on the pull-off, just past the head gate of Brush Creek Ranch. I stopped. Matt, who serves as Director of Activities and Outfitting for the Brush Creek Ranch Collection, stepped out, and we shook hands.

“Follow me over to the Sanger Ranch,” said Matt after an exchange of pleasantries. “It’s only about twenty minutes.”

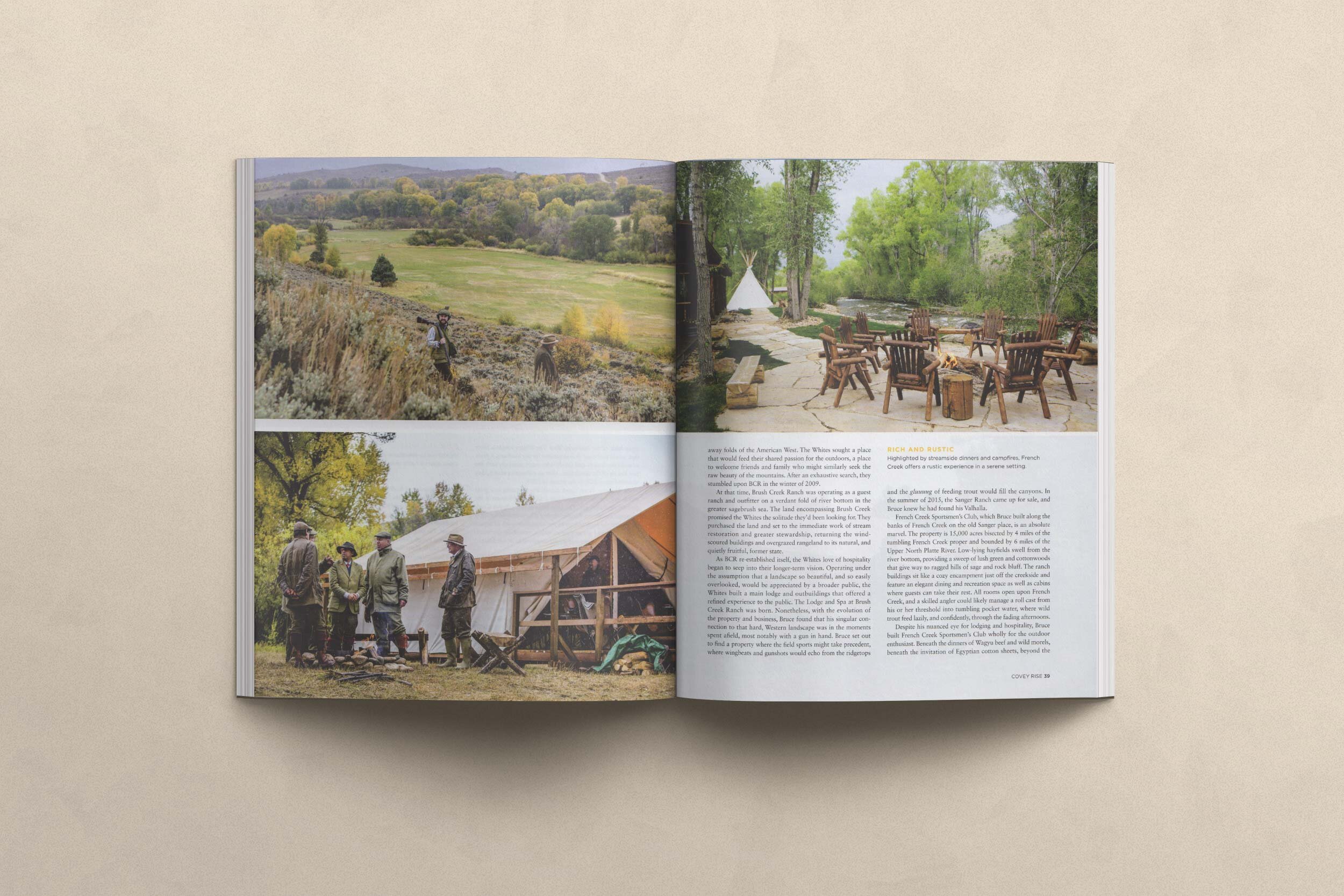

The Lodge and Spa at Brush Creek Ranch is the original offering in what is now a triad of holdings that includes BCR, The Magee Homestead, and French Creek Sportsmen’s Club (formerly the Sanger Ranch). The properties are situated around Saratoga, WY, nestled into rough country between the Medicine Bows and the Sierra Madre, on the eastern slope of the Continental Divide. All are owned by Bruce and Beth White who, in the later stages of a fruitful career in hotel ownership, development, and management, set out to find a personal sanctuary in the tucked-away folds of the American West. The White’s sought a place that would feed their shared passion for the outdoors, a place to welcome friends and family who might similarly seek the raw beauty of the mountains. After an exhaustive search they stumbled upon BCR in the winter of 2009.

At that time, Brush Creek Ranch was operating as a guest ranch and outfitter on a verdant fold of river bottom in the greater sagebrush sea. The land encompassing Brush Creek promised the Whites the solitude they’d been looking for. They purchased the land and set to the immediate work of stream restoration and greater stewardship, returning the wind-scoured buildings and overgrazed rangeland to its natural, and quietly fruitful, former state.

As BCR re-established itself, the White’s love of hospitality began to seep into their longer-term vison. Operating under the assumption that a landscape so beautiful, and so easily overlooked, would be appreciated by a broader public, the Whites built a main lodge and outbuildings that offered a refined experience to the public, and the Lodge and Spa at Brush Creek Ranch was born. Nonetheless, with the evolution of the property and business, Bruce found that his singular connection to that hard, western landscape was in the moments spent afield, most notably with a gun in hand. Though BCR, and later the Magee Homestead, would indeed afford guests the opportunity to hunt and shoot and fish, those activities were nestled among a much wider offering. Bruce, therefore, narrowed his focus, and set out to find a property where the field sports might take precedent, where wingbeats and gunshots would echo from the ridgetops and the “gluuuug” of feeding trout would fill the canyons. In the summer of 2015, the Sanger Ranch came up for sale, and Bruce knew he had found his Valhalla.

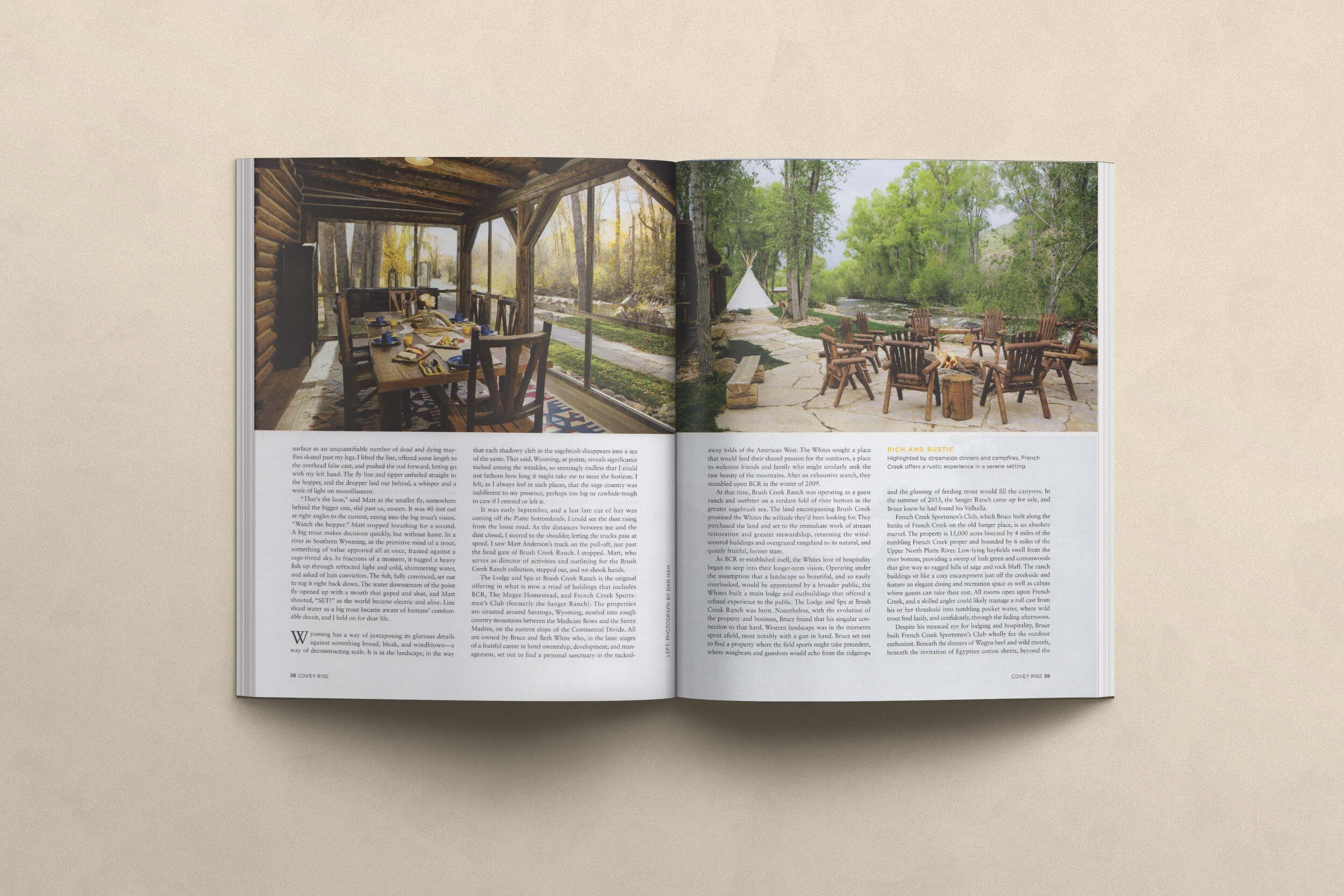

French Creek Sportsmen’s Club, which Bruce built along the banks of French Creek on the old Sanger place, is an absolute marvel. The property is 15,000 acres bisected by four miles of the tumbling French Creek proper and bounded by six miles of the Upper North Platte river. Low-lying hayfields swell from the river-bottom, providing a sweep of lush green and cottonwoods that gives way to ragged hills of sage and rock bluff. The ranch buildings sit like a cozy encampment just off the creek-side and feature an elegant log dining and recreation space, and low-slung cabins where guests can take their rest. All rooms open upon French Creek, and a skilled angler could likely manage a roll cast from his or her threshold into tumbling pocket water, where wild trout feed lazily, and confidently, through the fading afternoons.

Despite his nuanced eye for lodging and hospitality, Bruce built French Creek Sportsmen’s Club wholly for the outdoor enthusiast. Beneath the dinners of Wagyu beef and wild morels, beneath the invitation of Egyptian cotton sheets, beneath the sumptuous wine and bourbon collections that guest draw upon at will, the heartbeat of French Creek Sportsmen’s Club thrums in the land and water. This is a Sportsmen’s paradise, and Bruce White rightly assumes that the small groups that find themselves there will see the food, wine, and lodging as appendages to the main event. A dedicated staff resides on-property to serve up all the activities that an outdoorsman could ever wish for: shooters can indulge to their hearts’ content in helice, sporting clays, five-stand, and trap, and both pistol and long-range rifle ranges are accessible directly off the main verandah; driven and walk-up hunting for pheasants and partridge fills the autumn days, and roosters cackle from the bankside willows; anglers who wish to venture beyond their porch-side and French Creek’s home pools can enjoy walk-wade fishing on the Platte or French Creek, or float trips on the Platte or Encampment rivers. During my stay I was regaled with a story of a gentleman who landed a by-goodness twenty-six inch wild brown trout in a piece of creek he could have spit across, then made the short walk back to camp where chef Jon Guzman had the table laid with wine and a Wagyu tomahawk, the sage butter still melting on top.

It is just such layers of magnificence that are found among the grey-green and windswept wrinkles, in a swatch of land that hides such things well, rewarding those who look a little closer. French Creek Sportsmen’s Club is Wyoming at its most furtive, and its most magical…

*

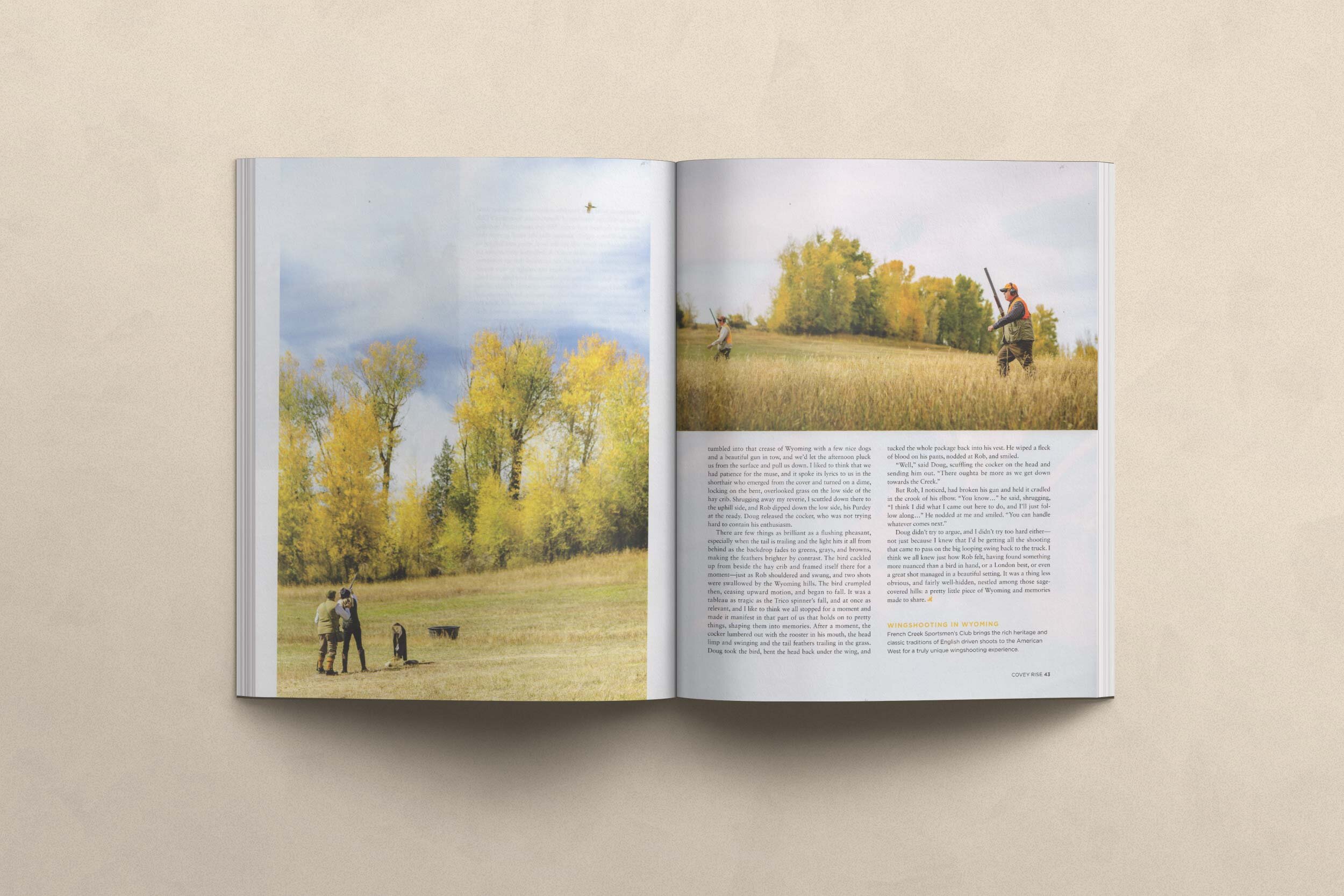

On the final evening of my visit, I joined a couple named Rob and Karen in a sunset bird hunt in one of the fresh-cut mowings just above French Creek. Doug Cannon, who is the primary guide and dog handler for all of the properties, arrived at the French Creek buildings with a trailer-full of dogs. The motivation for this late-day hunt was not so much to have the full and un-checked hunting experience that is FCR’s hallmark, but rather to get a few birds allocated to the new Purdey that Rob had recently taken delivery of. Ever one to appreciate a poetic gesture, I asked Rob if I might tag along.

We traced the course of French Creek downstream in Doug’s truck and turned off just above the confluence with the Platte, gaining elevation. Pheasants had already started pecking on the fringes of the ranch road, and that low autumn light had the hay stubble blushing emerald, the dust motes glinting as they fell. We parked at the top, midway up the length of the field, and Doug cut the engine. Rob, Karen and I spilled out and collected our things as Doug unsheathed the guns.

Rob’s new Purdey was indeed a thing of beauty, subtle and muted from a few feet back, but exquisitely precise in hand. He allowed me a good long look; the scrollwork was crisp and tight, perfectly lost beneath the nuanced purples, browns, and blue-blacks of freshly-varnished case-color.

“I wanted a beautiful setting to break in a beautiful gun,” he said and sighed, filling his vest pocket with shells.

Doug dropped a rangy shorthair and a little brown cocker and fastened the waist of his vest. He steered us towards the nearest strip of uncut grass cover, which in turn ended in the timbers of a decrepit hay crib. A hundred yards downhill, a rooster squirted from the cover and squawked, setting his wings to follow the contour of the land all the way back to French Creek. The cocker feinted as if to give chase, then looped back to Doug, bouncing in for a check with one of those grins that Cockers manage so easily. Doug smiled back; he looked over at us, invited Karen (who had opted just to walk) to take up a position at his side, and then sent his dogs down into the near strip of cover. The shorthair disappeared in a wide cast, just a nub of tail denoting his passage as he worked through the thick stuff. The cocker stayed close at Doug’s heel. We followed the dogs down the hill as the sun sank lower over the foothills of the Sierra Madre to our back.

As we walked through the hayfield and into the passage of an afternoon, I couldn’t help but get lost in the narrative unfolding. Here we were in a place so lush, in an afternoon so bright and lively, but enveloped in a greater swatch of dusty rangeland that was ostensibly no-man’s. We had tumbled into that crease of Wyoming with a few nice dogs and a beautiful gun in tow, and we’d let the afternoon pluck us from the surface and pull us down. I liked to think that we had patience for the muse… and it spoke its lyrics to us in the shorthair who emerged from the cover and turned on a dime, locking on the bent, overlooked grass on the low side of the hay crib. Shrugging away my reverie, I scuttled down there to the uphill side, and Rob dipped down the low side, his Purdey at the ready. Doug released the cocker, who was not trying hard to contain his enthusiasm.

There are few things as brilliant as a flushing pheasant, especially when the tail is trailing, and the light hits it all from behind, and the backdrop fades to greens and greys and browns, making the feathers brighter by contrast. The bird cackled up from beside the hay crib and framed itself there for a moment, just as Rob shouldered and swung, and two shots were swallowed by the Wyoming hills. The bird crumpled then, ceasing upward motion, and began to fall. It was a tableau as tragic as the Trico spinner-fall, and at once as relevant, and I like to think we all stopped for a moment and made it manifest in that part of us that holds on to pretty things, shaping them into memories. After a moment the cocker lumbered out with the rooster in his mouth, the head limp and swinging, the tail feathers trailing in the grass. Doug took the bird, bent the head back under the wing, and tucked the whole package back into his vest. He wiped a fleck of blood on his pants, and nodded at Rob, and smiled.

“Welp,” said Doug, scuffling the Cocker on the head, and sending him out. “There oughta be more as we get down towards the Creek.”

But Rob, I noticed, had broken his gun. He held it cradled in the crook of his elbow. “You know…” he said, shrugging, “I think I did what I came out here to do, and I’ll just follow along…” He nodded at me and smiled. “You can handle whatever pops up.”

Doug didn’t try to argue, and I didn’t try too hard either, and not just because I knew that I’d be getting all the shooting that came to pass on the big looping swing back to the truck. I think we all knew just how Rob felt, having found something more nuanced than a bird in hand or a London best or even a great shot managed in a beautiful setting. It was a thing less obvious, and fairly well-hidden, nestled among those sage-covered hills: a pretty little piece of Wyoming, and memories made to share.

First published in Covey Rise April/May 2020