The Sporting Art of Ogden Pleissner

Most of us interpret our world as an interplay of objects and actions translated into words that describe the twining of the two, words that, quite often, fall short. A graphic artist, a painter in particular, interprets his or her world, those same objects and actions, as fragments of light and shadow, color and gradation, negative space that informs its opposite, and vice-versa. Painters make meaning in smudges of color, glints of light, and only in stepping back recognize what they have seen in aggregate, something explained but without the frailty of words. This is the gift of the painter: the ability to catch moments like fireflies in a jar, moments that, when shared, can again quicken the heart. Painters make meaning with tools as pedestrian as tinted oil and watercolor, brushes and paper; the rest of us just stammer to harness what we saw and felt within the confines of our meager, spoken descriptions.

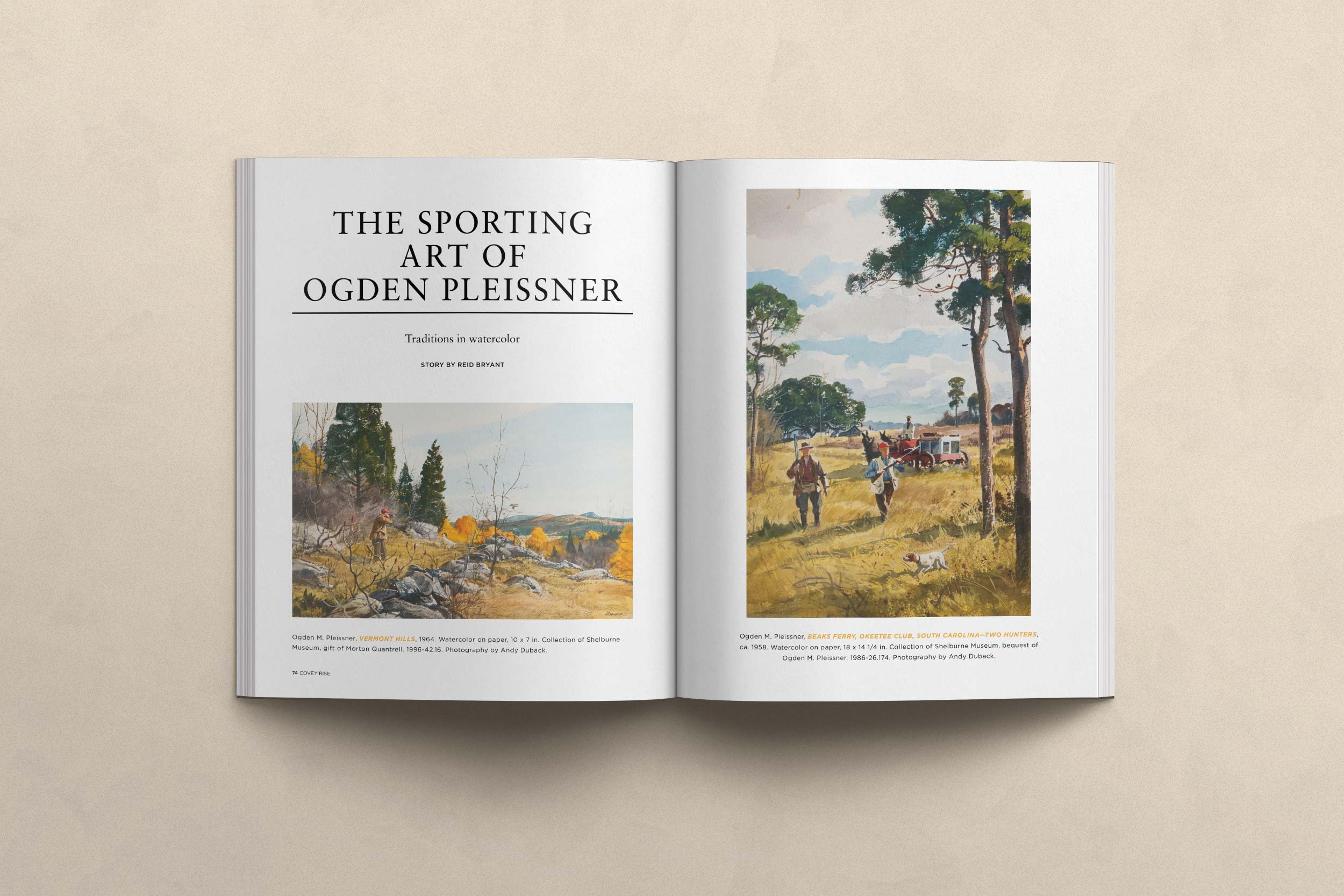

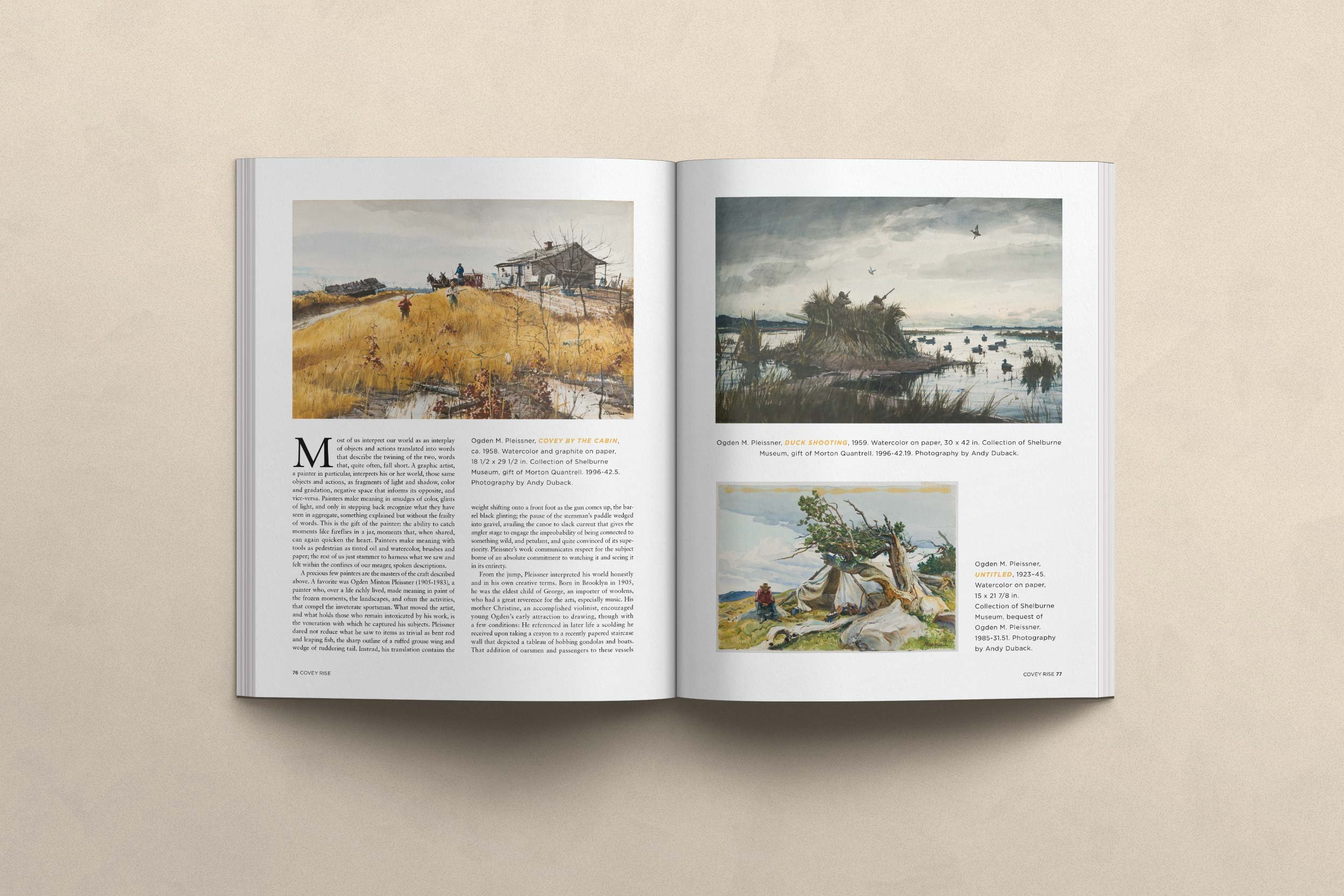

A precious few painters are the masters of the craft described above. A favorite was Ogden Minton Pleissner (1905-1983), a painter who, over a life richly lived, made meaning in paint of the frozen moments, the landscapes, and often the activities, that compel the inveterate sportsman. What moved the artist, and what holds those who remain intoxicated by his work, is the veneration with which he captured his subjects. Pleissner dared not reduce what he saw to items as trivial as bent rod and leaping fish, the sharp outline of a ruffed grouse wing and wedge of ruddering tail. Instead, his translation contains the weight shifting onto a front foot as the gun comes up, the barrel black glinting; the pause of the sternman’s paddle wedged into gravel, availing the canoe to slack current that gives the angler stage to engage the improbability of being connected to something wild, and petulant, and quite convinced of its superiority. Pleissner’s work communicates respect for the subject borne of an absolute commitment to watching it, and seeing it in its entirety.

From the jump, Pleissner interpreted his world honestly and in his own creative terms. Born in Brooklyn in 1905, he was the eldest child of George, an importer of woolens, who had a great reverence for the arts, especially music. His mother Christine, an accomplished violinist, encouraged young Ogden’s early attraction to drawing, though with a few conditions: he referenced in later life a scolding he received upon taking a crayon to a recently papered staircase wall that depicted a tableau of bobbing gondolas and boats. That addition of oarsmen and passengers to these vessels proved ill-advised and left 5-year-old Ogden with a sore bottom. The experience did little to dissuade him from his artistic path.

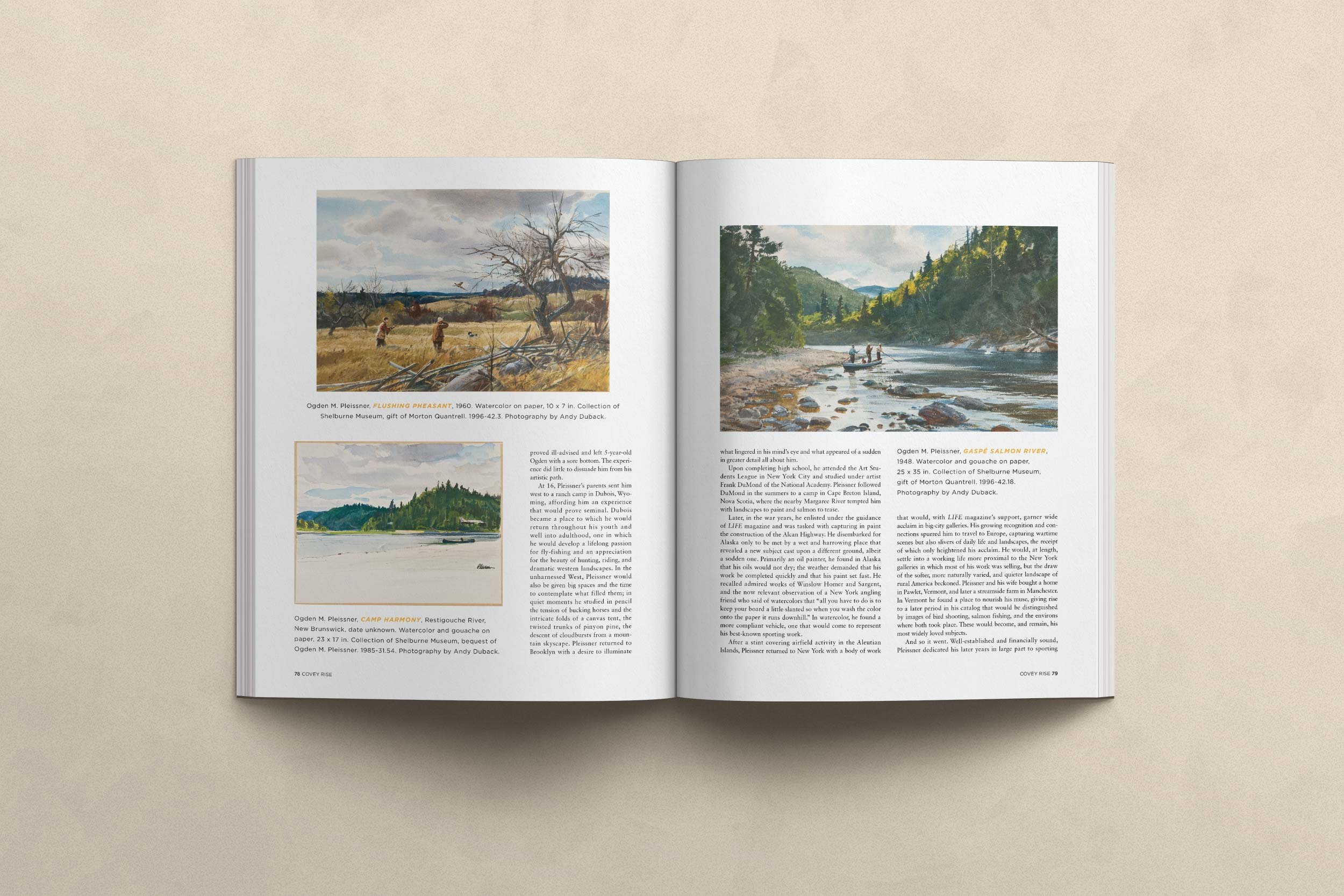

At 16, Pleissner’s parents sent him west to a ranch camp in Dubois, Wyoming, affording him an experience that would prove seminal. Dubois became a place to which he would return throughout his youth and well into adulthood, one in which he would develop a lifelong passion for fly fishing, and an appreciation for the beauty of hunting, riding, and dramatic western landscapes. In the unharnessed West, Pleissner would also be given big spaces and the time to contemplate what filled them; in quiet moments he studied in pencil the tension of bucking horses and the intricate folds of a canvas tent, the twisted trunks of Pinyon pine, the descent of cloudbursts from a mountain skyscape. Pleissner returned to Brooklyn with a desire to illuminate what lingered in his mind’s eye, and what appeared of a sudden in greater detail all about him.

Upon completing high school, he attended the Art Students League in New York City, and studied under artist Frank DuMond of the National Academy. Pleissner followed DuMond in the summers to a camp in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where the nearby Margaree River tempted him with landscapes to paint and salmon to tease. Later, in the war years, he enlisted under the guidance, of Life Magazine, and was tasked with capturing in paint the construction of the Alcan Highway. He disembarked for Alaska only to be met by a wet and harrowing place that revealed a new subject cast upon a different ground, albeit a sodden one. Primarily an oil painter, he found in Alaska that his oils would not dry; the weather demanded that his work be completed quickly and that his paint set fast. He recalled admired works of Winslow Homer and Sargent, and the now relevant observation of a New York angling friend who said of watercolors that “all you have to do is to keep your board a little slanted so when you wash the color onto the paper it runs downhill.” In watercolor, he found a more compliant vehicle, one that would come to represent his best-known sporting work.

After a stint covering airfield activity in the Aleutians, Pleissner returned to New York with a body of work that would, with Life Magazine’s support, garner wide acclaim in big city galleries. His growing recognition and connections spurred him to travel to Europe, capturing wartime scenes but also slivers of daily life and landscapes, the receipt of which only heightened his acclaim. He would, at length, settle into a working life more proximal to the New York galleries in which most of his work was selling, but the draw of the softer, more naturally varied, and quieter landscape of rural America beckoned. Pleissner and his wife bought a home in Pawlet, Vermont, and later a streamside farm in Manchester. In Vermont he found a place to nourish his muse, giving rise to a later period in his catalog that would be distinguished by images of bird shooting, salmon fishing, and the environs where both took place. These would become, and remain, his most widely loved subjects.

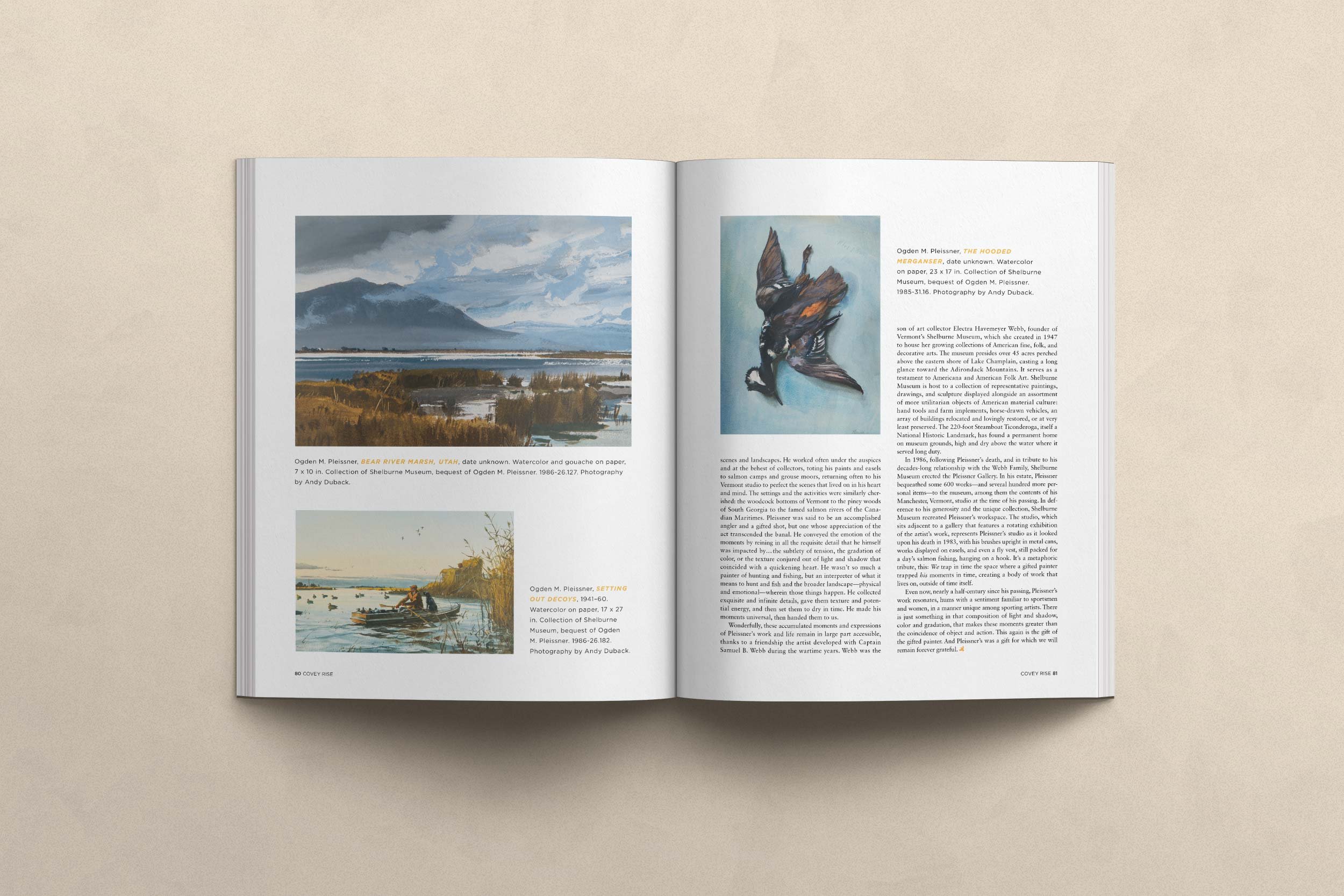

And so it went. Well-established and financially sound, Pleissner dedicated his later years in large part to sporting scenes and landscapes. He worked often under the auspices and at the behest of collectors, toting his paints and easels to salmon camps and grouse moors, returning often to his Vermont studio to perfect the scenes that lived on in his heart and mind. The settings and the activities were similarly cherished: the woodcock bottoms of Vermont to the piney woods of south Georgia to the famed salmon rivers of the Canadian Maritimes. Pleissner was said to be an accomplished angler and a gifted shot, but one whose appreciation of the act transcended the banal. He conveyed the emotion of the moments by reigning in all the requisite detail that he himself was impacted by… the subtlety of tension, the graduation of color, or the texture conjured out of light and shadow that coincided with a quickening heart. He wasn’t so much a painter of hunting and fishing, but an interpreter of what it means to hunt and fish, the broader landscape, physical and emotional, wherein those things happen. He collected exquisite and infinite details, gave them texture and potential energy, and then set them to dry in time. He made his moments universal, then handed them to us.

Wonderfully, these accumulated moments and expressions of Pleissner’s work and life remain in large part accessible, thanks to a friendship the artist developed with Capt. Samuel B. Webb during the wartime years. Webb was the son of art collector Electra Havemeyer Webb, founder of Vermont’s Shelburne Museum, which she created in 1947 to house her growing collections of American fine, folk, and decorative arts. The museum presides over 45 acres perched above the eastern shore of Lake Champlain, casting a long glance toward the Adirondack Mountains. It serves as a testament to Americana and American Folk Art; alongside a varying catalog of exhibits, Shelburne Museum is host to a collection of representative paintings, drawings, and sculpture displayed alongside an assortment of more utilitarian objects of American material culture: hand tools and farm implements, horse-drawn vehicles, an array of buildings re-located and lovingly restored, or at very least preserved. The 220 ft. Steamboat Ticonderoga, itself a National Historic Landmark, has found a permanent home on museum grounds, high and dry above the water where it served long duty.

In 1986, following Pleissner’s death, and in tribute to his many-decades relationship with the Webb Family, Shelburne Museum erected the Pleissner Gallery. In his estate, Pleissner bequeathed some 600 works, and several hundred more personal items, to the museum, among them the contents of his Manchester, Vermont studio at the time of his passing. In deference to his generosity and the unique collection, Shelburne Museum recreated Pleissner’s workspace. The studio, which sits adjacent to a gallery that features a rotating exhibition of the artist’s work, represents Pleissner’s studio as it looked upon his death in 1983, with his brushes upright in metal cans, works displayed on easels, and even a fly vest, still packed for a day’s salmon fishing, hanging on a hook. It’s a metaphoric tribute, this: we trap in time the space where a gifted painter trapped his moments in time, creating a body of work that live on, outside of time itself.

Even now, nearly a half-century since his passing, Pleissner’s work resonates, hums with a sentiment familiar to sportsmen and women, in a manner unique among sporting artists. There is just something in that composition of light and shadow, color and gradation, that makes these moments greater than the coincidence of object and action. This again is the gift of the gifted painter. And Pleissner’s was a gift for which we will remain forever grateful.