Thanksgiving

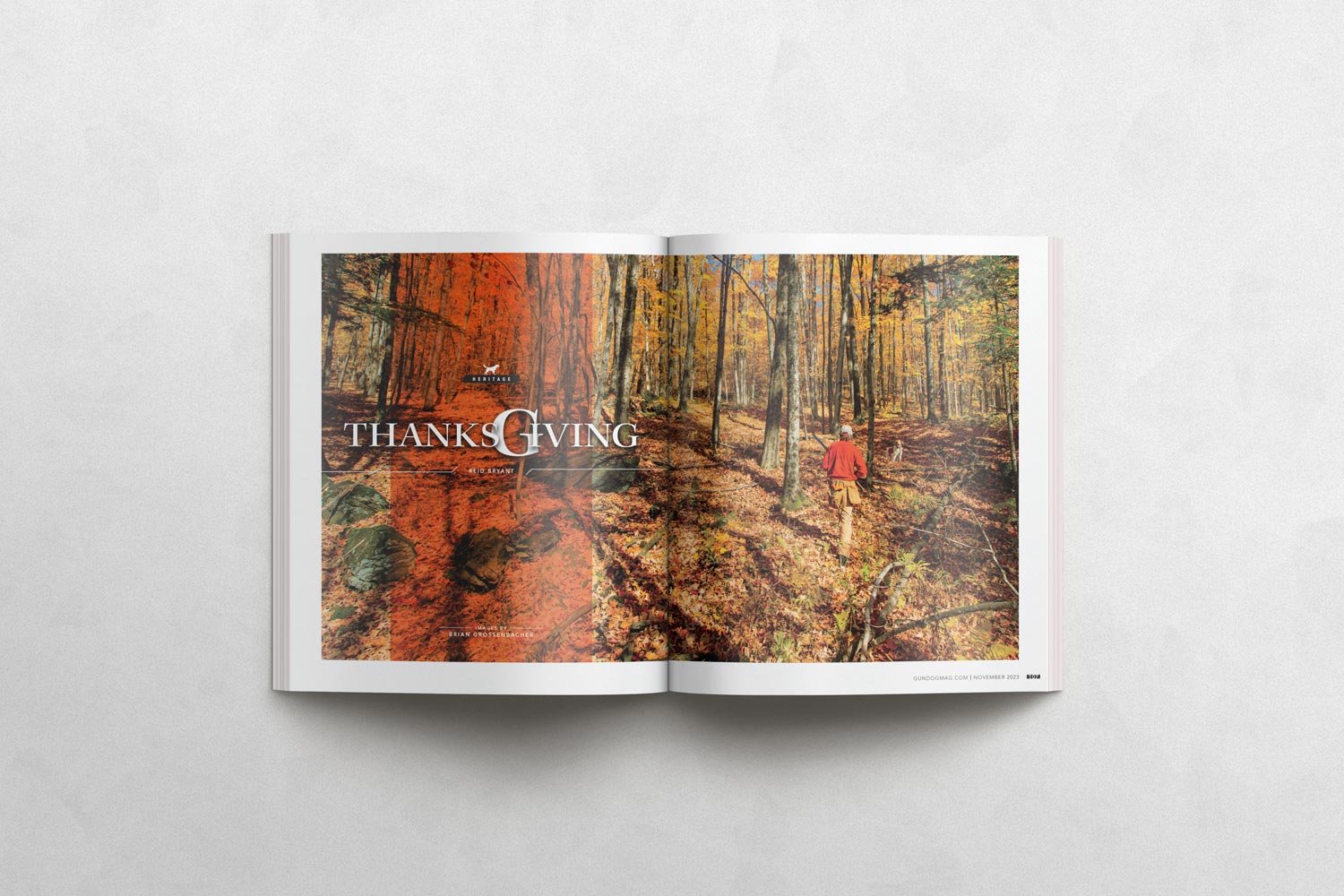

We were up on the mountain on a Saturday noon, somewhere off the Stratton access road in a place I’d never been. Steve was driving. He knew the place well enough, had even hunted it earlier in the week, toppling two resident woodcock whose education in the perils of a New England October proved terminal. All the days since had been warm. Steve figured that the flight birds were still a week or so north in Quebec, but that there were bound to be a few more residents up there in that overlooked orchard. He was leaning forward over the steering wheel, less concerned with the road ahead than the quality of what cover composed the woody tangles to our right and to our left. He was drinking a Coke-flavored slushie from the gas station in Winhall. It was an indulgence he unapologetically reserved for trips to-and-from the grouse woods. Steve was happy as a clam.

Up where the road went to washboards and ruts, it leveled out. Steve slowed and pulled off the shoulder and onto the berm. It was a glowing afternoon: the birches were turning already, and the popples that rose in clumps and islands were just outpacing them. What grass and scrub made up the opens created a palette of golds and greens. Ancient apple trees persevered here and there, their arthritic fingers twisting skyward, bearing what stunted fruit they could cling to. A stone wall ran perpendicular to the road. Where the land fell off to the north and east the treetops only came to eye-level, and from where we sat inside Steve’s truck we could see the whole spine of the Green Mountains, and if we imagined hard, the Whites of New Hampshire beyond.

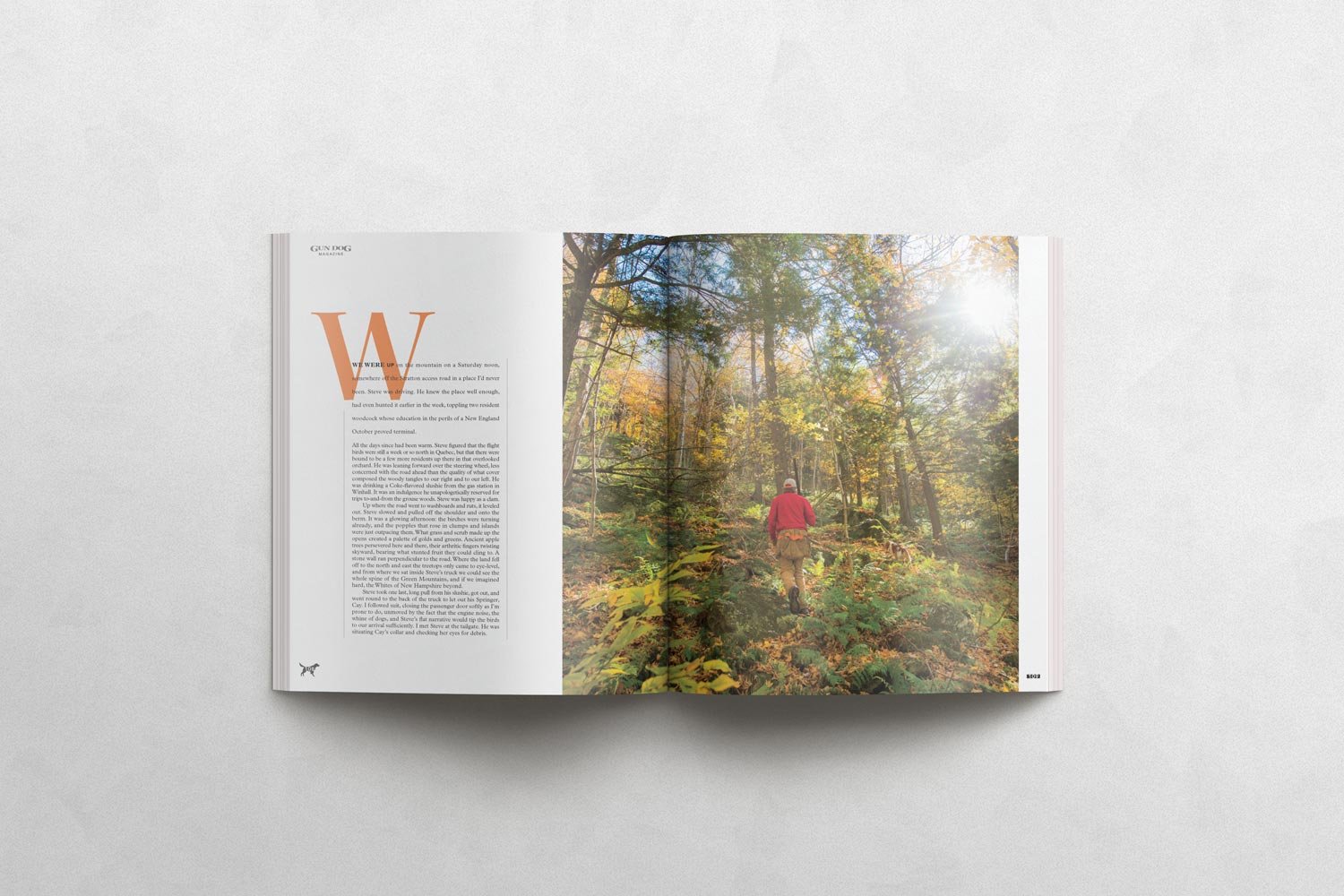

Steve took one last, long pull from his slushie, got out, and went round to the back of the truck to let out his Springer, Cay. I followed suit, closing the passenger door softly as I’m prone to do, unmoved by the fact that the engine noise, the whine of dogs, and Steve’s flat narrative would tip the birds to our arrival sufficiently. I met Steve at the tailgate. He was situating Cay’s collar and checking her eyes for debris.

“Want to run them together?” he asked, nodding at my Brittany, Collins, who was casting baleful glances through the lattice of his crate door. “It’s fine with me if you like.”

We’d been alternating the dogs cover by cover all morning, and Cay had clearly been the finder, routing birds out of the tangles and rose bushes with fair consistency. Our shooting had been unremarkable, but that was to be expected. Neither one of us paid it much mind. Collins, a good-natured fellow with a penchant for tiptoeing through the chalk-splattered bottoms, had yet to find a bird. A few olfactory enticements, fine and far off as the fly-fishers say, had lured him on some casts well out of sight, producing flushes that we never saw and barely heard. I’d long ago lost much faith in him as a bird dog, but he was a guileless companion, one I always enjoyed having along for the walk. Since Steve was offering, I collared him up, fixed the bell at his throat, and let him jump off the tailgate. The dogs shook themselves out, sprinkled the roadside dust in observation of their arrival, and readied themselves for good things. We grabbed guns, stuffed shells in our pockets, and readied ourselves for the same.

I always liked hunting with Steve. He balanced enthusiasm with low expectations, and he always saw a day in the woods as a good day indeed. A bird in hand was never to him a foregone conclusion, so in that regard, I could shrug off any burden that might be lain on old Collins or me. The currency Steve collected, however, was made of the miles he walked, and he ate up the cover in great big gulps, navigating the thorns with a mix of abandon and delight fueled by sugar. He set off in earnest, aimed for the wood line and the densest knot of cover, while I took the more forgiving path to the inside. I tried to keep pace. Cay for her part ducked like a ferret and disappeared, her jingle bell fast becoming the only indicator of her presence nearby. Collins, like me, meandered through the easier stuff, and I allowed my focus on him to recede, as I knew he’d be weighing the path of least resistance against the one towards the promise of birds. He was never prone to put too much tender skin in the game.

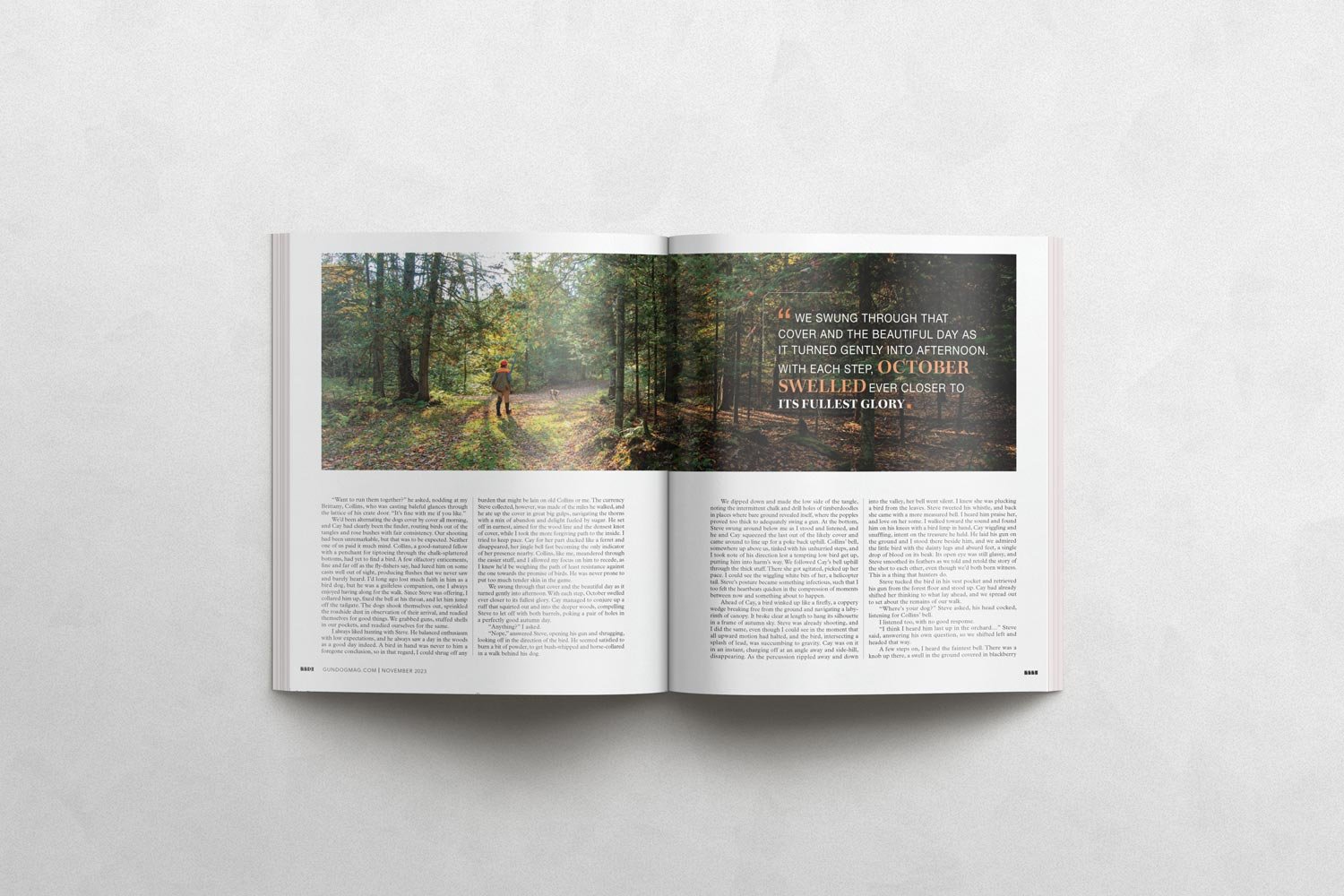

We swung through that cover and a beautiful day as it turned gently into afternoon. With each step, October swelled ever closer to its fullest glory. Cay managed to conjure up a ruff that squirted out and into the deeper woods, compelling Steve to let off with both barrels, poking a pair of holes in a perfectly good autumn day.

“Anything?” I asked.

“Nope,” answered Steve, opening his gun and shrugging, looking off in the direction of the bird. He seemed satisfied to burn a bit of powder, to get bush-whipped and horse-collared in a walk behind his dog.

We dipped down and made the low side of the tangle, noting the intermittent chalk and drill holes of timberdoodles in places where bare ground revealed itself, where the popples proved too thick to adequately swing a gun. At the bottom, Steve swung around below me as I stood and listened, and he and Cay squeezed the last out of the likely cover and came around to line up for a poke back uphill. Collins’ bell, somewhere up above us, tinked with his unhurried steps, and I took note of his direction lest a tempting low bird get up, putting him into harm’s way. We followed Cay’s bell uphill through the thick stuff. There she got agitated, picked up her pace. I could see the wiggling white bits of her, a helicopter tail. Steve’s posture became something infectious, such that I too felt the heartbeats quicken in the compression of moments between now and something about to happen.

Ahead of Cay, a bird winked up like a firefly, a coppery wedge breaking free from the ground and navigating a labyrinth of canopy. It broke clear at length to hang its silhouette in a frame of autumn sky. Steve was already shooting, and I did the same, even though I could see in the moment that all upward motion had halted, and the bird, intersecting a splash of lead, was succumbing to gravity. Cay was on it in an instant, charging off at an angle away and side-hill, disappearing. As the percussion rippled away and down into the valley, her bell went silent. I knew she was plucking a bird from the leaves. Steve tweeted his whistle, and back she came with a more measured bell. I heard him praise her, and love on her some. I walked toward the sound and found him on his knees with a bird limp in hand, Cay wiggling and snuffling, intent on the treasure he held. He laid his gun on the ground and I stood there beside him, and we admired the little bird with the dainty legs and absurd feet, a single drop of blood on its beak. Its open eye was still glassy, and Steve smoothed its feathers as we told and retold the story of the shot to each other, even though we’d both born witness. This is a thing that hunters do.

Steve tucked the bird in his vest pocket and retrieved his gun from the forest floor and stood up. Cay had already shifted her thinking to what lay ahead, and we spread out to set about the remains of our walk.

“Where’s your dog?” Steve asked, his head cocked, listening for Collins’ bell.

I listened too, with no good response.

“I think I heard him last up in the orchard…” Steve said, answering his own question, so we shifted left and headed that way.

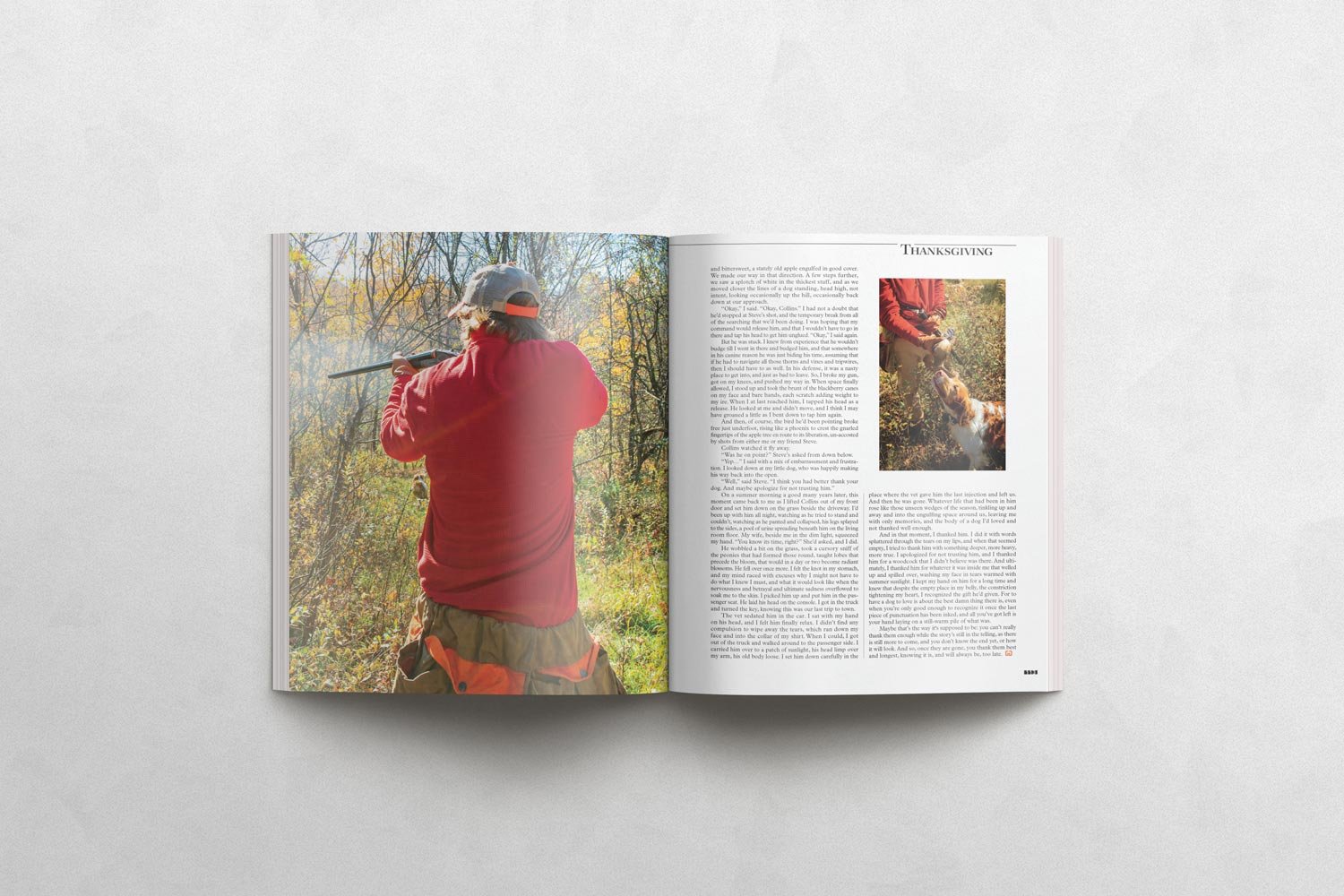

A few steps on, I heard the faintest bell. There was a knob up there, a swell in the ground covered in blackberry and bittersweet, a stately old apple engulfed in good cover. We made our way in that direction. A few steps further, we saw a splotch of white in the thickest stuff, and as we moved closer the lines of a dog standing, head high, not intent, looking occasionally up the hill, occasionally back down at our approach.

“Okay,” I said. “Okay, Collins.” I had not a doubt that he’d stopped at Steve’s shot, and the temporary break from all of the searching that we’d been doing. I was hoping that my command would release him, and that I wouldn’t have to go in there and tap his head to get him unglued. “Okay,” I said again.

But he was stuck. I knew from experience that he wouldn’t budge till I went in there and budged him, and that somewhere in his canine reason he was just biding his time, assuming that if he had to navigate all those thorns and vines and tripwires, then I should have to as well. In his defense, it was a nasty place to get into, and just as bad to leave. So, I broke my gun, got on my knees, and pushed my way in. When space finally allowed, I stood up and took the brunt of the blackberry canes on my face and bare hands, each scratch adding weight to my ire. When I at last reached him, I tapped his head and as a release. He looked at me and didn’t move, and I think I may have groaned a little as I bent down to tap him again.

And then, of course, the bird he’d been pointing broke free just underfoot, rising like a phoenix to crest the gnarled fingertips of the apple tree en route to its liberation, un-accosted by shots from either me or my friend Steve.

Collins watched it fly away.

“Was he on point?” Steve’s asked from down below.

“Yep…” I said with a mix of embarrassment and frustration. I looked down at my little dog, who was happily making his way back into the open.

“Well,” said Steve. “I think you had better thank your dog. And maybe apologize for not trusting him.”

*

On a summer morning a good many years later, this moment came back to me as I lifted Collins out of my front door and set him down on the grass beside the driveway. I’d been up with him all night, watching as he tried to stand and couldn’t, watching as he panted and collapsed, his legs splayed to the sides, a pool of urine spreading beneath him on the living room floor. My wife, beside me in the dim light, squeezed my hand. “You know its time, right?” She’d asked, and I did.

He wobbled a bit on the grass, took a cursory sniff of the peonies that had formed those round, taught lobes that precede the bloom, that would in a day or two become radiant blossoms. He fell over once more. I felt the knot in my stomach, and my mind raced with excuses why I might not have to do what I knew I must, and what it would look like when the nervousness and betrayal and ultimate sadness overflowed to soak me to the skin. I picked him up and put him in the passenger seat. He laid his head on the console. I got in the truck and turned the key, knowing this was our last trip to town.

The vet sedated him in the car. I sat with my hand on his head, and I felt him finally relax. I didn’t find any compulsion to wipe away the tears, which ran down my face and into the collar of my shirt. When I could, I got out of the truck and walked around to the passenger side. I carried him over to a patch of sunlight, his head limp over my arm, his old body loose. I set him down carefully in the place where the vet gave him the last injection and left us. And then he was gone. Whatever life that had been in him rose like those unseen wedges of the season, tinkling up and away and into the engulfing space around us, leaving me with only memories, and the body of a dog I’d loved and not thanked well enough.

And in that moment, I thanked him. I did it with words spluttered through the tears on my lips, and when that seemed empty, I tried to thank him with something deeper, more heavy, more true. I apologized for not trusting him, and I thanked him for a woodcock that I didn’t believe was there. And ultimately, I thanked him for whatever it was inside me that welled up and spilled over, washing my face in tears warmed with summer sunlight. I kept my hand on him for a long time and knew that despite the empty place in my belly, the constriction tightening my heart, I recognized the gift he’d given. For to have a dog to love is about the best damn thing there is, even when you’re only good enough to recognize it once the last piece of punctuation has been inked, and all you’ve got left is your hand laying on a still-warm pile of what was.

Maybe that’s the way it's supposed to be: you can’t really thank them enough while the story’s still in the telling, as there is still more to come, and you don’t know the end yet, or how it will look. And so, once they are gone, you thank them best and longest, knowing it is, and will always be, too late.

First Published in Gundog Magazine