Black Dirt Bobwhites

Writer Milan Kundera, meditating on the human tendency to look back with longing, noted that “the Greek word for "return" is nostos. Algos means "suffering." So nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return.”

Nostalgia, viewed thus, can pose a temptingly melancholic place to reside, albeit an evocative one. Indeed, nostalgia always seems to be painted in somber tones and wrinkled imagery: in looking back we recognize something that we once had, something that is now irretrievable, something to be yearned for. In considering such loss the clouds roll in, casting long and looming shadows over the heart that thwart the light that remains above.

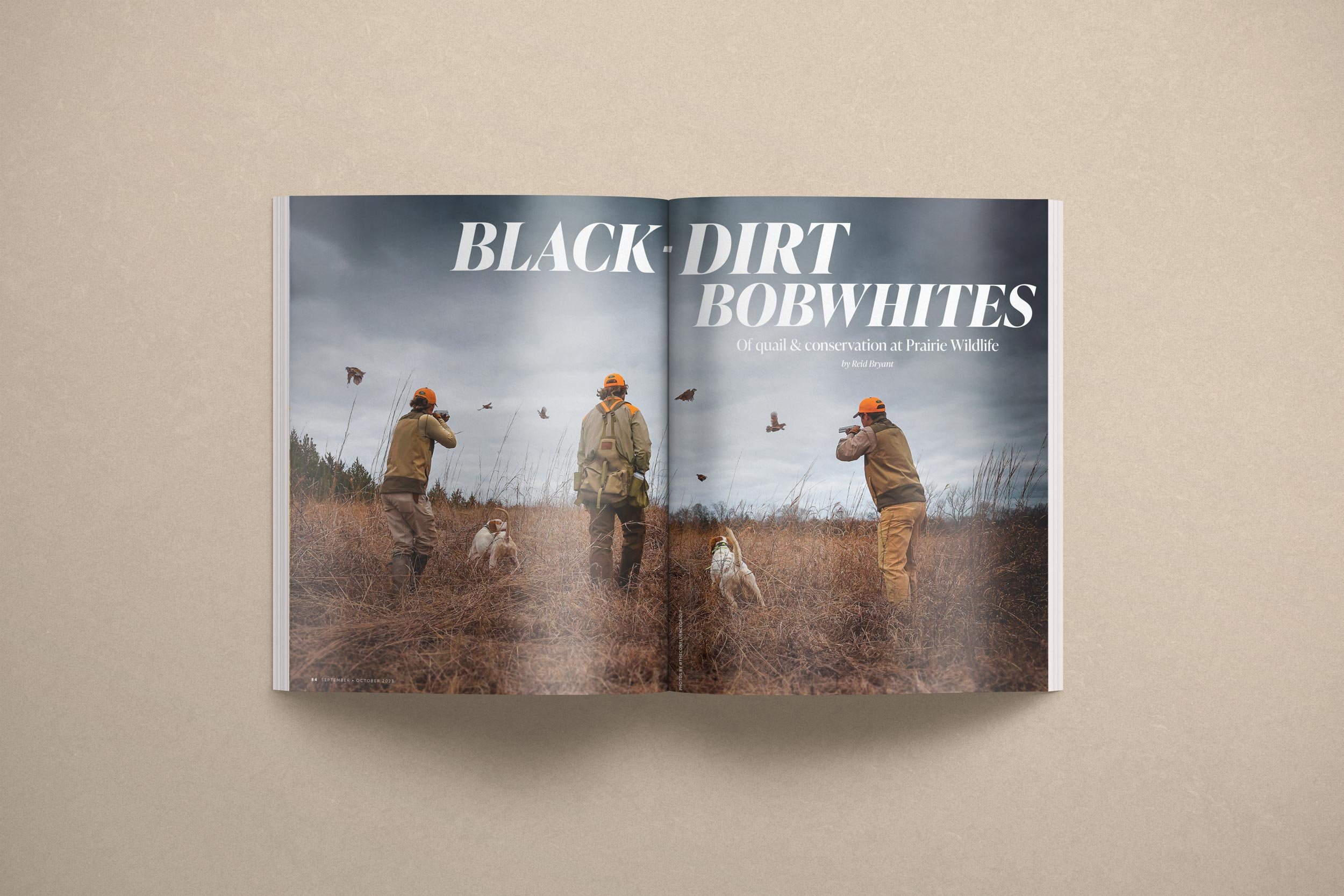

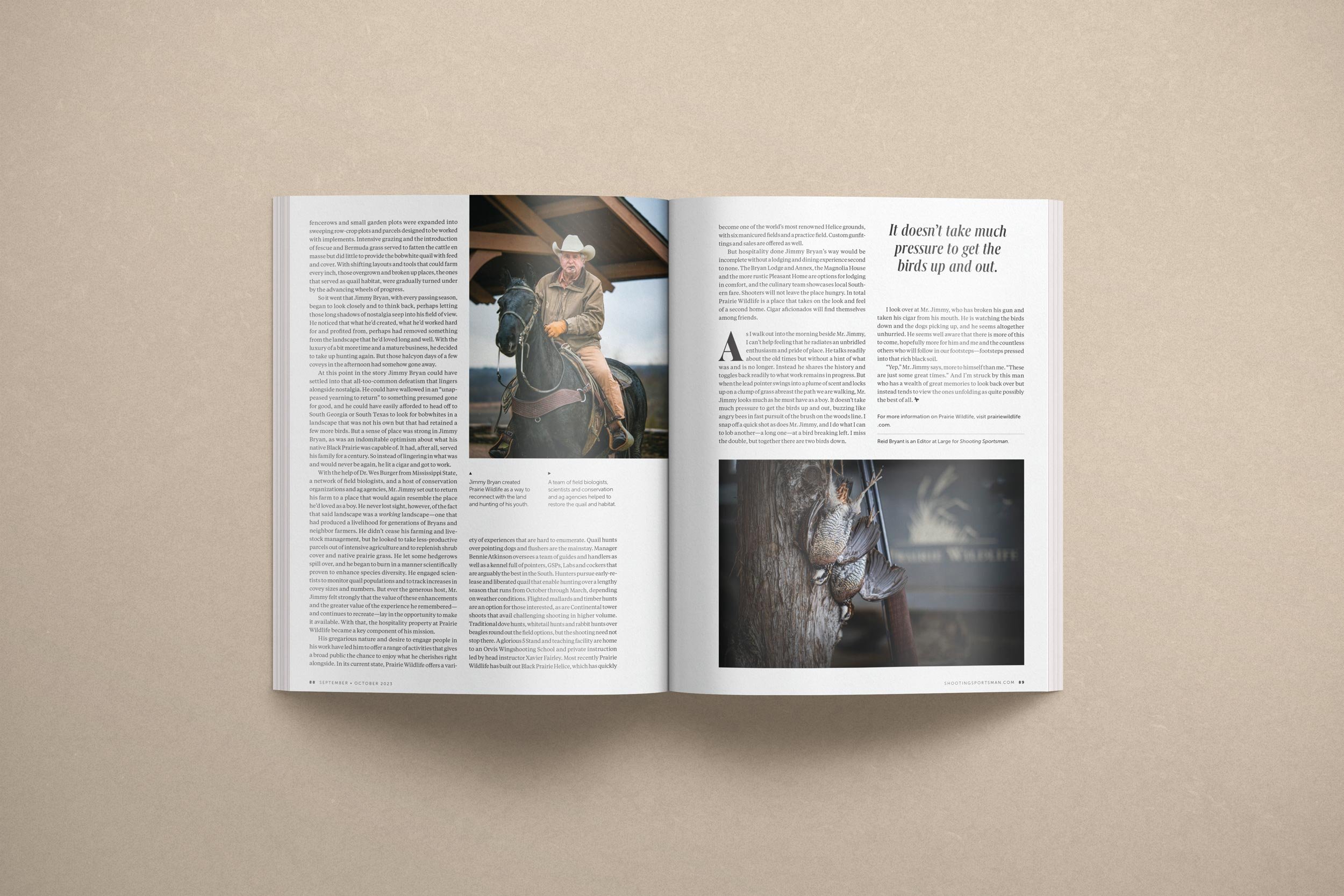

In his middle eighties, Mr. Jimmy Bryan seems to study nostalgia from a decidedly sunnier vantage. At the edge of a patchwork field bordered by scrub hedgerows, he breaks a dainty Francotte double and rests it on his shoulder. He takes one of several cigars from his breast pocket, removes the cellophane, and bites through the cap. He flicks a wooden match and holds the flame to his face, cupping the whole operation in hands that evidence a lifetime of hard and honest work. Smoke swirls, obscuring his face for a moment, and once the ember has taken, he shakes the flame away. He drops the blackened matchstick and grinds it into the soil with the toe of his boot. As the smoke clears, his features reconstitute: ruddy cheeks and dancing eyes, tufts of wiry silver hair poking from beneath the brim of a buff-colored Stetson. He smiles easily.

“Used to be, when I was a young man, we had a lot of birds, and a lot of acreage to hunt on. In the afternoons I could get off work, come out here with my dog, and find four or five coveys before dark. It was the greatest feeling in the world.” Leaving this statement to swirl around in a haze of cigar smoke, Mr. Jimmy pokes a couple shells into his gun. A pointer is already down, making a broad cast, and words that another man would have left behind to punctuate a conclusion now sift gently skyward. Mr. Jimmy is solidly and happily present, looking out over a field of prairie grass and into the promise of more birds, more points and flushes, and memories not yet made. “Let’s go…” he says and steps off into what he has worked hard to implement for himself and others; a future every bit as bright, maybe more so, than the past he reveres, but feels no need to yearn for.

This is the story of Prairie Wildlife, a story inextricable from the one of Mr. Jimmy Bryan, a man whose work in the name of bobwhite quail and habitat conservation seems to delight him still. Prairie Wildlife is a hunting destination sure, a composite of 5000 acres of fields and forests in West Point, Mississippi. It’s a Lodge and a hunting property where folks can come and hunt a wedge of Mississippi’s last remaining Black Prairie, a tallgrass ecosystem fueled by the rich black soil that shows between the grass clumps and mown pathways. Prairie Wildlife offers premium lodging, dining, and a host of shooting sports, including an Orvis Wingshooting school and tailored instruction in “the art of shooting flying”. At root, however, it is a destination for those who appreciate land and birds and the perpetuation of both… a sportsman’s paradise in many ways, but also a working model of what is possible when hard science, a sense of place, and a conservation ethos encounter a man like Jimmy Bryan, a man who decides to make his vision manifest on the landscape.

West Point is a small town in a classically agrarian part of eastern Mississippi. Mr. Jimmy grew up here, and through his early life explored a countryside comprised of cotton fields and cattle pastures, patchwork small farms and sprawling market gardens interrupted by wooded hedgerows. There were quail aplenty then, as well as rabbits and other small critters, presenting endless opportunities for a boy to hunt and fish and ride his walking horse. Mr. Jimmy’s grandfather owned the meat market in town, and when Jimmy was a young boy his father and one uncle started a meat packing business of their own. Working summers in that business, Mr. Jimmy learned the livestock trade, and upon completing school, he jumped right in, soon realizing the excitement of working and trading cattle. He bought and sold and shipped livestock, accumulated land upon which to run his feeding operations, and pieced together the infrastructure with which to hold and ship an increasing number of cattle. In relatively short order, and by virtue of straight dealing and tireless effort, he built a small empire. Prairie Livestock Company would become one of the largest shippers of cattle in the country, and Jimmy Bryan would become a name known, and widely respected, among ranchers and cattlemen everywhere.

But with success came sacrifice. As Prairie Livestock grew, and Mr. Jimmy found his time occupied increasingly by the demands of work and family, he found less and less opportunity to saddle a horse and grab a fistful of shotshells, to pursue the little birds that had filled the days edges with their lonesome whistles. When, still a young man, he lost his bird dog to a passing car, he didn’t replace him. He focused instead on keeping pace with a livestock and farming practice that was growing in efficiency and profitability. Gone were the days of small farms and overgrown corners; fields that had once been interrupted by woody fencerows and small garden plots were expanded into sweeping row crop plots and parcels designed to be worked with implements. Intensive grazing and the introduction of fescue and Bermuda grass served to fatten the cattle en masse but did little to provide the Bobwhite quail with feed and cover. With shifting layouts and tools that could farm every inch, those overgrown and broken up places, the ones that served as quail habitat, were gradually turned under by the advancing wheels of progress.

So it went that Jimmy Bryan, with every passing season, began to look closely and to think back, perhaps letting those long shadows of nostalgia seep into his field of view. He noticed that what he’d created, what he’d worked hard for and profited from, perhaps removed something from the landscape that he’d loved long and well. With the luxury of a bit more time and a mature business, he decided to take up hunting again. But those halcyon days of a few coveys in the afternoon had somehow gone away.

At this point in the story, Jimmy Bryan could have settled into that all-too-common defeatism that lingers alongside nostalgia. He could have wallowed in an “unappeased yearning to return” to something presumed gone for good, and he could have easily afforded to head off to South Georgia or South Texas, to go looking for bobwhites in a landscape that was not his own, but that had retained a few more birds. But a sense of place was strong in Jimmy Bryan, as was an indomitable optimism about what his native Black Prairie was capable of. It had, after all, served his family for a century. So, instead of lingering in what was and would never be again, he lit a cigar and got to work.

With the help of Dr. Wes Burger from Mississippi State, a network of field biologists, and a host of conservation orgs and ag agencies, Mr. Jimmy set out to return his farm to a place that would again resemble the place he loved as a boy. He never lost sight, however, of the fact that said landscape was a working landscape, one that had produced a livelihood for generations of Bryans and neighbor farmers. He didn’t cease his farming and livestock management, but he looked to take less-productive parcels out of intensive agriculture, and to replenish shrub cover and native prairie grass. He let some hedgerows spill over, and he began to burn in a manner scientifically proven to enhance species diversity. He engaged scientists to monitor quail populations and to track increases in covey size and number. But, ever the generous host, Mr. Jimmy felt strongly that the value of these enhancements, and the greater value of the experience he remembered (and continues to re-create), lay in the opportunity to make it available. With that, the hospitality property at Prairie Wildlife became a key component of his mission.

Jimmy’s gregarious nature and desire to engage people in his work have led him to offer a range of activities that offer a broad public the chance to enjoy what he cherishes right alongside. In its current state, Prairie Wildlife offers a variety of experiences that are hard to enumerate. Quail hunts over pointing dogs and flushers are the mainstay. Manager Bennie Atkinson oversees a team of guides and handlers, as well as a kennel of pointers, GSP’s, labs, and cockers that are arguably the best in the south. Hunters pursue early-release and liberated quail that enable hunting over a lengthy season that runs October 1 to April, depending on weather conditions. Flighted mallards and timber hunts are an option for those interested, as are formal continental tower shoots that avail challenging shooting in higher volume. Traditional dove hunts, whitetail hunts, and rabbit hunts over beagles round out the field options, but the shooting need not stop there. A glorious five-stand and teaching facility is home to an Orvis Wingshooting School and private instruction led by head instructor Xavier Fairley. Most recently, Prairie Wildlife has built out Black Prairie Helice, which has quickly become one of the world’s most renowned Helice grounds, with six manicured fields in place and a practice field. Custom gun fittings and sales are options for the retail-oriented.

But hospitality done Jimmy Bryan’s way would be incomplete without a lodging and dining experience second to none. The Bryan Lodge and Annex, the Magnolia house, and the more rustic Pleasant Home are all options for lodging in comfort, and the culinary team showcases local southern fare. Shooters will not leave the place hungry. In total, Prairie Wildlife is a place that takes on the look and feel of a second home. Cigar aficionados will find themselves among friends.

As I walk out into the morning beside Mr. Jimmy, and can’t help but feel that he radiates an unbridled enthusiasm and pride of place. He talks readily about the old times but without a hint of what was and is no longer. Instead, he shares the history, and toggles back readily to what work remains in progress. But when the lead pointer swings into a plume of scent and locks up on a clump of grass abreast the path we are walking, Mr. Jimmy looks much as he must have as a boy. It doesn’t take much pressure to get the birds up and out, buzzing like angry bees in fast pursuit of the brush on the woods line. I snap off a quick shot as Mr. Jimmy does the same, and I do what I can to lob another shot, a long one, at a bird breaking left. I miss the double, but together there are two birds down. I look over at Mr. Jimmy, who has broken his gun and taken his cigar from his mouth. He is watching the birds down and the dogs picking up, and he seems altogether unhurried. He seems well aware that there is more of this to come, hopefully more for him and me and the countless others that have and will follow in our footsteps, footsteps pressed into that rich black soil.

“Yep,” he says, more to himself than me. “These are just some great times.” And I’m struck by this man, who has a wealth of great memories to look back over, but instead tends to view the ones unfolding as quite possibly the very best of all.