The Magic of Driven Shooting

To my left, in the dwindling light, my friend Andrew Pierce stood with his heels almost touching Scotland’s River Tay. Facing inland, he, like me, watched a hillside that less swelled up from the gloom than sagged out of it. The intricacies of treetops revealed themselves only at intervals out of the mist, and we stood there trying to untangle the earth from the sky, listening hard for the sound of the keeper’s horn and the muffled thwack of the beaters’ flags. We knew that somewhere well above us a wave of people and dogs, of footsteps and sound and motion, would soon nudge a surge of pheasants into collective advance. In the minutes to follow, the space between us and them would become compressed and the volume of birds would assume critical mass, terminal pressure and then take flight, spilling over the treetops, over our heads and, unless we dictated otherwise, over the River Tay and clear toward Dundee.

There is something wonderful about driven shooting encompassed in an orchestrated preamble, a beginning that has definition, and a distinct end, whether we wish the latter to arrive or not. The anticipatory moments before the horn sat juxtaposed against a fading day and provided me a moment to look around. I listened to the small sounds of all that choreography, the lapping water and the whine of dogs; I smelled wet wool and brackish water mud; I watched little drops condense on my gun barrels and run down its rib to disappear beneath the forend wood.

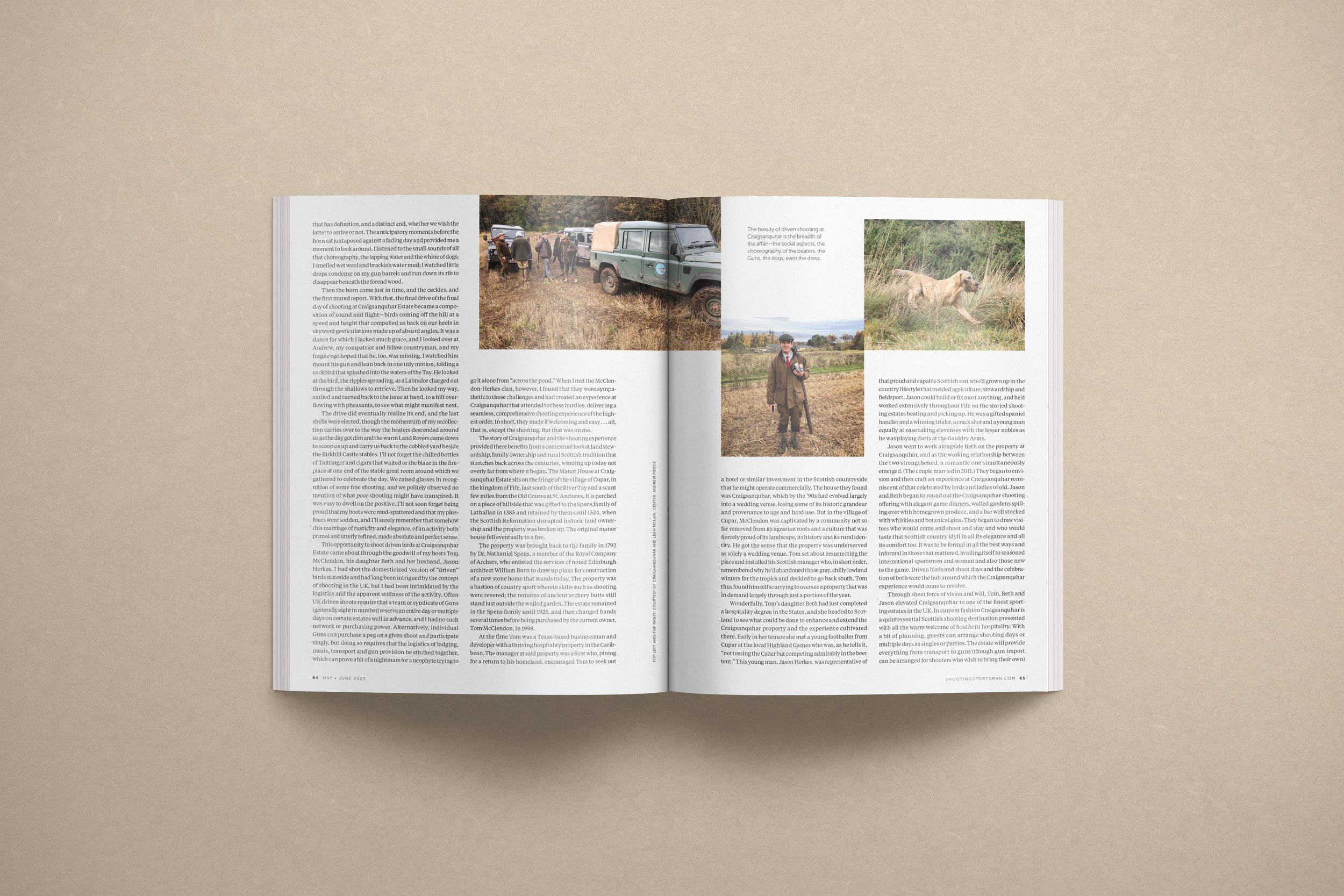

Then the horn came just in time, and the cackles, and the first muted report. With that, the final drive of the final day of shooting with Craigsanquhar Estate became a composition of sound and flight—birds coming off the hill at a speed and height that compelled us back on our heels in skyward gesticulations made up of absurd angles. It was a dance for which I lacked much grace, and I looked over at Andrew, my compatriot and fellow countryman, and my fragile ego hoped that he, too, was missing. I watched him mount his gun and lean back in one tidy motion, folding a cockbird that splashed into the waters of the Tay. He looked at the bird, the ripples spreading, as a Labrador charged out through the shallows to retrieve. Then he looked my way, smiled and turned back to the issue at hand, to a hill overflowing with pheasants, to see what might manifest next.

The drive did eventually realize its end, and the last shells were ejected, though the momentum of my recollection carries over to the way the beaters descended around us as the day got dim and the warm Land Rovers came down to scoop us up and carry us back to the cobbled yard beside the Birkhill Castle stables. I’ll not forget the chilled bottles of Taittinger and cigars that waited or the blaze in the fireplace at one end of the stable great room around which we gathered to celebrate the day. We raised glasses in recognition of some fine shooting, and we politely observed no mention of what poor shooting might have transpired. It was easy to dwell on the positive. I’ll not soon forget being proud that my boots were mud-spattered and that my plus-fours were sodden, and I’ll surely remember that somehow this marriage of rusticity and elegance, of an activity both primal and utterly refined, made absolute and perfect sense.

This opportunity to shoot driven birds at Craigsanquhar Estate came about through the goodwill of my hosts Tom McClendon, his daughter Beth and her husband, Jason Herkes. I had shot the domesticized version of “driven” birds stateside and had long been intrigued by the concept of shooting in the UK, but I had been intimidated by the logistics and the apparent stiffness of the activity. Often UK driven shoots require that a team or syndicate of Guns (generally eight in number) reserve an entire day or multiple days on certain estates well in advance, and I had no such network or purchasing power. Alternatively, individual Guns can purchase a peg on a given shoot and participate singly, but doing so requires that the logistics of lodging, meals, transport and gun provision be stitched together, which can prove a bit of a nightmare for a neophyte trying to go it alone from “across the pond.” When I met the McClendon-Herkes clan, however, I found that they were sympathetic to these challenges and had created an experience at Craigsanquhar that attended to these hurdles, delivering a seamless, comprehensive shooting experience of the highest order. In short, they made it welcoming and easy . . . all, that is, except the shooting. But that was on me.

The story of Craigsanquhar and the shooting experience provided there benefits from a contextual look at land stewardship, family ownership and rural Scottish tradition that stretches back across the centuries, winding up today not overly far from where it began. The Manor House at Craigsanquhar Estate sits on the fringe of the village of Cupar, in the kingdom of Fife, just south of the River Tay and a scant few miles from the Old Course at St. Andrews. It is perched on a piece of hillside that was gifted to the Spens family of Lathallan in 1385 and retained by them until 1524, when the Scottish Reformation disrupted historic land ownership and the property was broken up. The original manor house fell eventually to a fire.

The property was brought back to the family in 1792 by Dr. Nathaniel Spens, a member of the Royal Company of Archers, who enlisted the services of noted Edinburgh architect William Burn to draw up plans for construction of a new stone home that stands today. The property was a bastion of country sport wherein skills such as shooting were revered; the remains of ancient archery butts still stand just outside the walled garden. The estate remained in the Spens family until 1925, and then changed hands several times before being purchased by the current owner, Tom McClendon, in 1998.

At the time Tom was a Texas-based businessman and developer with a thriving hospitality property in the Caribbean. The manager at said property was a Scot who, pining for a return to his homeland, encouraged Tom to seek out a hotel or similar investment in the Scottish countryside that he might operate commercially. The house they found was Craigsanquhar, which by the ’90s had evolved largely into a wedding venue, losing some of its historic grandeur and provenance to age and hard use. But in the village of Cupar McClendon was captivated by a community not so far removed from its agrarian roots and a culture that was fiercely proud of its landscape, its history and its rural identity. He got the sense that the property was underserved as solely a wedding venue. Tom set about resurrecting the place and installed his Scottish manager who, in short order, remembered why he’d abandoned those gray, chilly lowland winters for the tropics and decided to go back south. Tom thus found himself scurrying to oversee a property that was in demand largely through just a portion of the year.

Wonderfully, Tom’s daughter Beth had just completed a hospitality degree in the States, and she headed to Scotland to see what could be done to enhance and extend the Craigsanquhar property and the experience cultivated there. Early in her tenure she met a young footballer from Cupar at the local Highland Games who was, as he tells it, “not tossing the Caber but competing admirably in the beer tent.” This young man, Jason Herkes, was representative of that proud and capable Scottish sort who’d grown up in the country lifestyle that melded agriculture, stewardship and fieldsport. Jason could build or fix most anything, and he’d worked extensively throughout Fife on the storied shooting estates beating and picking up. He was a gifted spaniel handler and a winning trialer, a crack shot and a young man equally at ease taking elevenses with the lesser nobles as he was playing darts at the Gauldry Arms.

Jason went to work alongside Beth on the property at Craigsanquhar, and as the working relationship between the two strengthened, a romantic one simultaneously emerged. (The couple married in 2011.) They began to envision and then craft an experience at Craigsanquhar reminiscent of that celebrated by lords and ladies of old. Jason and Beth began to round out the Craigsanquhar shooting offering with elegant game dinners, walled gardens spilling over with homegrown produce, and a bar well stocked with whiskies and botanical gins. They began to draw visitors who would come and shoot and stay and who would taste that Scottish country idyll in all its elegance and all its comfort too. It was to be formal in all the best ways and informal in those that mattered, availing itself to seasoned international sportsmen and women and also those new to the game. Driven birds and shoot days and the celebration of both were the hub around which the Craigsanquhar experience would come to revolve.

Through sheer force of vision and will, Tom, Beth and Jason elevated Craigsanquhar to one of the finest sporting estates in the UK. In current fashion Craigsanquhar is a quintessential Scottish shooting destination presented with all the warm welcome of Southern hospitality. With a bit of planning, guests can arrange shooting days or multiple days as singles or parties. The estate will provide everything from transport to guns (though gun import can be arranged for shooters who wish to bring their own) to trips to the local tweed shop, if guests desire to dress the part. The Craigsanquhar property itself is relatively small but centrally located: Guests shoot on one or more of the venerable sporting estates that surround the Craigsanquhar Manor house. Birkhill Castle, Teasses, Lindores, Naughton House and several more are all in close agreement with Jason, and shooting can take place on any of these properties and more, depending on dates, conditions and the variety and number of birds desired. Though red-legged partridge and pheasants are the mainstay of the standard 300-or-so-bird driven days, smaller days and “mini-driven” days can avail shooters to a mixed bag that includes mallards, woodcock, wood pigeons and even snipe. With lodging and gourmet meals served at the Craigsanquhar property, guests really need only arrive dressed and ready for the event at hand; shooters are escorted by a fleet of Land Rovers to the field each day, generally driving no farther than 25 minutes over hill and dale, and retreating to a rustic venue on the day’s estate grounds for a grand, formal and exquisitely curated lunch. Traditional elevenses are, of course, provided in the field.

I have to say that going into my first UK driven shoot I was a bit intimidated. In my mind’s eye it all threatened to be so stuffy and laden with etiquette. There were no doubt obscure rules I was sure I would embarrass myself—and my hosts—by breaking. I needed only to shoot beside Jason and Tom for a morning to have my concerns dispelled. Both men were courteous and properly attired and formal in their deference to guests, as was the gamekeeper, George Elliot, who was emphatic in his policies around safety and decorum. But at the same time they made it all fun—as, of course, a driven day should be. When the shooting started, both Tom and Jason became giddy as schoolboys, beaming over their great shots and chiding each other good-naturedly over the birds that soared past unscathed. Occasionally I saw them become so engaged watching the other Guns that they failed to shoot at all. At the end of each drive both men made the rounds visiting Guns, laughing and back-slapping and handing out sour-lemon candies. Their love of the sport was infectious.

The subtle genius of the Craigsanquhar experience, as I saw it, lies in the ability of Tom, Jason and the keepers on the various estates to immerse shooters in the experience at a graduated pace. Noting that my fellow Guns on the trip were largely new to the game, we spent the first two days shooting smaller bags on smaller drives but getting a feel for the countryside and the varying demands of different birds and properties. Each day consisted of five or so small drives, or “mini-driven” shoots, which at times enabled Guns to walk with the beaters through a small wood under the close eye of the keeper. It was in this fashion that I took my first Eurasian woodcock and missed my first many more. There were several small drives that presented relatively easy, open shots, with pegs lined up in gently sloping cut cropfields, and others that provided far more testing shots, depending on the peg. I recall one small drive on the Birkhill Estate wherein I was positioned at the bottom of a craggy ravine, and the window of sky within which I might shoot seemed infinitesimally small and the birds traversing it unfathomably high. I managed a bird or two, I think, while Jason’s dad, Jim Herkes, who’d joined us for the day, fared much better on the adjacent peg. I suppose Jim was better accustomed to tall birds that you get a look at only after they are disappearing from view.

Those first two days, however, set a rhythm for us, allowing us to witness a full spectrum of shooting and to see nearly all the bird species available for sport. We also got the lay of the land, saw some beautiful country and became a part of it, at least for a while. In traveling to shoot, it’s this latter component that I may love the most: Only when I’ve had the chance to explore the shadowy, overgrown or less-traveled pieces of a place do I feel any less of a tourist. And only when I’ve tasted the flesh of it do I realize any lasting relationship.

After that last day afield, after the toasts were made and the cigars reduced to ash, we returned to the house at Craigsanquhar to rest a bit and change for dinner (which would feature roast whole woodcock, pheasant breasts with cream and wild mushrooms, and the jam-basted tenderloins of a plump roe deer). I took a hot shower and sat down on my bed to revisit the day, the past few days and the experience that had been laid out before me. It occurred to me, sitting there on the second floor of a hundreds-year-old home, that the true art of driven shooting is not in the shooting at all. Of course, I would remember the shooting but to a greater degree what preceded it, buttressed it and followed it up. The magic at Craigsanquhar lay in the orchestration, the accumulated planning and maneuvering, the months spent coordinating with keepers and landowners to ensure that spaniels and birds were in top form. There were the Rovers that were warmed and ready to pick us up and drop us off; the keeper George, who steered lines of beaters through hundred-acre woods like a master navigator, conjuring pheasants into flight by the subtle inflections of a flag. There was Beth, who somehow turned a stone barn at the Birkhill stable into a grand dining room and the table into something laid as if for kings or despots. And there was the feeling that somehow, as a collective, we were all there to keep a tradition alive and to realize the act of doing so as necessary, as valuable. It was all a monumental undertaking requiring much forethought but was executed with such apparent ease and grace.

I tucked in my shirt and straightened my tie and opened the door of my room, stepping out into the hallway just as Andrew did. Neither of us is generally the “dress-for-dinner” sort, but this felt appropriate—a simple and emphatic gesture of respect for the experience we’d just had. I could tell that Andrew, like me, was scheming an excuse to come do this again, to be a small and celebrated part of something so exquisite. As we made the bottom of the stairs, Jason met us with two pint glasses of bitter and smiled. “We were waitin’ for ye,” he said, gesturing toward the alcove where a piper in full dress was just beginning to work the bag nestled between his elbow and ribs. As the piper leaned into it, squawked his way closer and then caught hold of the first reedy bars of “Scotland the Brave,” I again paused, looked around and observed that uncommon sense of pride, of belongingness. I felt less a guest and more a part of something bigger—far bigger than a team of Guns on pegs. Maybe that is the real magic of driven shooting and all that surrounds it: It makes you a part of something complex, time-honored and lovely, something done well because it is well worth doing.

Or maybe that is just the magic of driven shooting as Craigsanquhar does it.

For more information on Craigsanquhar Estate, visit craigsanquhar.com.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine