The Bird Familiar

If you peel back the layers of North American bird hunting to expose the core, you will find grouse. Centuries of manhandling have made cackling roosters and coveying quail the poster children of our uplands, but nothing has the romance of ruffed grouse. Perhaps I feel this way because grouse have doggedly resisted man’s compunction for domestication; they are the true natives, with a sense of place and purpose that defies us. Maybe it’s the bird’s remarkable physical adaptations borne of harsh places—cold, dry and windswept places which, in some cases, have also become obsolete. But more than likely it’s that grouse live in quiet corners where I would otherwise not go were I not in pursuit of their clucking flushes and thundering departures. I’d otherwise have no reason to wander miles through shin-deep prairie grass, to brave the alder tangles and blackberry thickets, to climb to thin-air elevation, or weave drunkenly through copses of spruce and dwarfed fir.

Perhaps what makes grouse wonderful is their ability to make bird hunters out of us, the bird hunters we aspire to be.

I suppose it would be silly to belittle a species with superlatives, but any sportsman worth his salt has a critter that gets in his blood, and beds down in his soul. For me, it’s always been Bonasa umbellus, the stately ruffed grouse; they are, I dare say, my favorite. My love affair with ruffs began years ago, in the coverts of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom where I then lived. In that region, they are colloquially referred to as partridge, a moniker which, when afforded a lilting Vermont accent, makes them all the more endearing. I hunted them dogless with a wobbly twelve gauge through the October afternoons of young adulthood, slinking through the popple whips and apple-strewn hedgerows around my hilltop home. Flushes were, as the fly-fishers say, fine and far off, often resulting in something barely audible and unworthy of a shot. At other times, I’d flush birds by nearly stepping on them, and waste two shots getting a good look at a bird only after the chambers were empty. I humbly recall that my first ruff was a bird that rose with another out of the conifer brush behind Tom O’Hanlon’s deer camp. I fired my two barrels and watched the birds bend off, seemingly unscathed. A few hundred disheartened steps deeper into the woods, I found a bird on her back in the throes. When I got to her she expired, a single pellet having lodged someplace vital, but without the immediate impact of a full load of 8’s. I held that grouse and knew full well what a gift I’d been given. That bird remains at the pinnacle of the memories I see when I close my eyes on winter evenings, and think back over blessed days afield.

My ruffed grouse hunting had taken on a certain aesthetic, and a tonal quality all its own. Ruffed grouse became for me synonymous with maple syrup and rotting apples, with the faraway lowing of Holsteins at milking time, and rime ice on the puddles. They flitted through associations with pipe smoke and wool plaid and knee-high rubber boots, inhabiting memories tinged with fir sap and hickory salt, and bell-wearing Brittany’s working close. They marked New England’s secret places with the circumspect reserve that described New Englanders themselves: grouse became for me a synchrony of people and place and wildlife that were part of my identity too. The paucity of birds to bag played an essential, Puritanical role. What bugged me no end were the fellows I knew out West who would shrug at my myopia and show me pictures of the ruffs they’d shot with arrows while elk hunting. “Ruffed grouse are stupid,” they’d say with a smile. “I killed the last one I saw with a stick!” The species they described was clearly not the one that I’d grown to know and love, a bird that had an innate ability to confound and compel that was limitless.

This idea that my bird’s cowboy cousins could be so different prodded me long enough that I finally went West to see for myself, leaving behind my wool plaid, and fearing the prospect of Mrs. Butterworth’s at breakfast. Fortunately I had Tim Linehan to help me through.

Tim is a New Hampshire guy who went West long ago for a bigger version of what he’d grown to love at home. Dissatisfied with the Yankee assumption that we lie in the bed we’ve made for ourselves, he simply made a new bed, a bigger sort, this one in northern Montana. There the trout were where they should be, eating on top and fighting with clean hearts. There the whitetails coursed the hillsides, more fretful at the prospects of grizzlies and wolves than commuter traffic and habitat loss. And there too, in the aspen thickets and alder runs, were familiar, barred-tailed birds, as innocent and perfect as children. But Tim was to find, and to show me, that things are not altogether what they seem. Friends would describe him with that old idiom that begins “You can take the boy out of New England….” They could have said the same for the ruffs of Montana’s Yaak Valley.

On a sunny October morning, we set out in search of birds. The hillsides of northwest Montana are verdant and thick, rising in a majestic swell of a place that leaves the craggy drama to the landscapes farther south. It looks for all the world like northern Vermont, minus the Holsteins and steeple-strewn villages. Moving up out of the valley, the coverts were recognizable too: gravel roads that gave way to popple whips, brushy corners, overgrown spur roads and log landings. I could have been at home, had the sky not been so big, but I forgot that too when I saw a bird fly across the truck hood. How Tim could keep going up, and not stop right there in a grouse hunter’s arcadia, I could barely understand.

A mile or so further on, we pulled off the road at a logging trace. Tim’s setter Maisey was collared and ready, and we put her down and tied our boots. This hunting was familiar, enough so to make me assume that the incidence of birds would be similarly lean. I stepped into the brush and pushed through it, tracking Maisey as she worked past the massive trunks towards an alder run. There, with the canopy miles above us, we walked two-abreast alongside the seep and the tangle, letting Maisey take the hard road down the middle. I kept reminding myself that there would be no woodcock to distract us, and that the points and flushes would be thundery and swift. But then I wondered if the stories I had heard were true, and into my mind crept a worrisome thought: What if these western birds were as dumb as they said? What if they embarrassed themselves with a complete absence of self-preservation? What if they sat stupidly on limbs, refusing to fly? What if the shots were easy? What if western ruffed grouse hunting robbed me of my ideals, tainted the regard with which I held these birds, threatening me to re-think an identity that had grown to rely on them as scarce and near impossible, in all of the ways they had been for me back East?

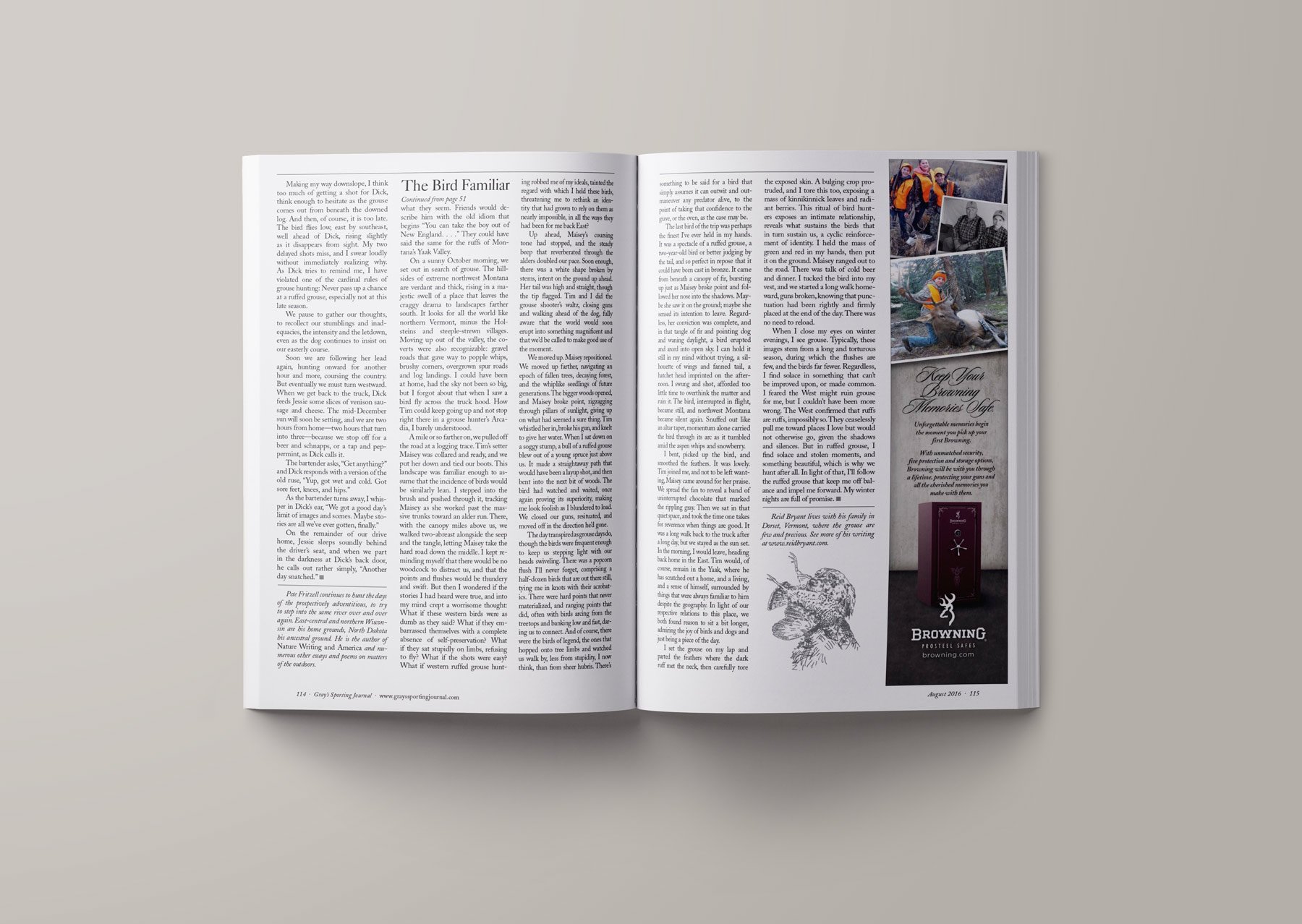

Up ahead, Maisey’s coursing tone had stopped, and the steady beep that reverberated through the alders doubled our pace. Soon enough, there was a white shape broken by stems, intent on the ground up ahead. Her tail was high and straight, though the tip flagged. Tim and I did the grouse shooter’s waltz, closing guns and walking ahead of the dog, fully aware that the world would soon erupt into something magnificent and that we’d be called to make good use of the moment.

We moved up. Maisey re-positioned. We moved up farther, navigating an epoch of fallen trees, decaying forest, and the whip-like seedlings of future generations. The bigger woods opened, and Maisey broke point, zigzagged off into pillars of sunlight, giving up on what had seemed a sure thing. Tim whistled her in, broke his gun, and knelt down to give her water. I sat down on a soggy stump. A bull of a ruffed grouse blew out of a young spruce just above us, made a straightaway path that would have been a lay-up of a shot, and then bent into the next bit of woods. The bird had, as they do the world over, watched and waited, proving its superiority once again, making me look like a fool as I blundered to load with futile dexterity. We closed our guns, got re-situated, and moved off in the direction he’d gone.

The day transpired as grouse days do, though the birds were frequent enough to keep us stepping light, with our heads on swivels. There was a popcorn flush I’ll never forget, comprised of a half-dozen birds that are out there still, tying me in knots with their acrobatics. There were hard points that never materialized, and ranging points that did, often with birds arcing from the treetops and banking low and fast, daring us to connect. And of course, there were the birds of legend, the ones that hopped up onto tree limbs and watched us walk by, less from stupidity I now think than from sheer hubris. There’s something to be said for a bird that simply assumes it can outwit and out-maneuver any predator alive, to the point of taking that confidence to the grave, or the oven, as the case may be.

The last bird of the trip was the finest, maybe the finest I’ve ever held in my hands. It was a spectacle of a ruffed grouse, a two-year-old bird or better by the tail, and so perfect in repose that it could have been cast in bronze. It came out from beneath a canopy of fir, bursting up from the ground just as Maisey broke point and followed her nose and the impending exodus into the shadows. Maybe she saw it on the ground; maybe she sensed its intention to leave, better suited than I, after all, for such native intelligence. Regardless, her conviction was complete, and in that tangle of fir and pointing dogs and waning daylight, a bird erupted and arced into open sky. I can hold it now still in my mind without trying, a silhouette of wings and fanned tail, a hatchet head imprinted on the afternoon. I swung and shot, afforded the privilege of too little time to overthink the matter and thereby ruin it. The bird, interrupted in flight, became still, and northwest Montana became silent again. Snuffed out like an altar taper, momentum alone carried the bird through its arc as it tumbled down amid the aspen whips and snowberry.

I bent and picked up the bird, and smoothed the feathers. It was lovely. Tim joined me, and Maisey came around for her praise. She was not to be left wanting. We spread the fan as you do, revealing a band of uninterrupted chocolate that marked the rippling gray. Then we all just sat there in that quiet space, and took the time one takes for reverence, when one knows things are good. It was a long walk back to the truck after a long day, but we stayed as the sun set. In the morning, I would leave, heading back home in the East. Tim would, of course, remain in the Yaak, in the place where he has scratched out a home, and a living, and a sense of himself, surrounded by things that were always familiar to him despite the geography. In light of our respective relations to this place, we both found reason to sit a bit longer, admiring the joy of birds and dogs and just being a piece of a day.

I set the grouse on my lap and parted the feathers where the dark ruff met the neck, and I carefully tore the exposed skin. A bulging crop protruded, and I tore this too, exposing a mass of kinnickinnick leaves and radiant berries. This ritual of bird hunters, exposes an intimate relationship, reveals what sustains the birds that in turn sustain us, a cyclic reinforcement of identity. I held the mass of green and red in my hands for a moment, then put it on the ground. Maisey ranged out to the road. There was talk of cold beer and dinner. I tucked the bird into my vest, and we started a long walk homeward, guns broken, knowing that punctuation had been rightly and firmly placed at the end of a wonderful day. There was no need to re-load.

When I close my eyes on winter evenings, I see grouse. Typically, these images stem from a long and torturous season, during which the flushes are few, and the birds far fewer. Regardless, I find solace in something that can’t be improved upon, or made common. I feared the West might ruin grouse, but I couldn’t have been more wrong. The West confirmed that ruffs are ruffs, impossibly so. They ceaselessly seem to pull me towards places I love but would not otherwise go, given the shadows and silences. But in ruffed grouse I find solace and stolen moments, and something beautiful, which is why we hunt after all. In light of that, I’ll follow the ruffed grouse that keep me off balance and impel me forward. My winter nights are full of promise.

First published Gray's Sporting Journal