On a Snowy Morning

Paulson put some new-leased ground in corn that year just in time to get blindsided by September rain that pushed harvest out a week or two. Water filled the depressions and sent the river almost over its banks, and even the marauding bears steered clear of the mud. By the time things dried out, Paulson still had a few hundred acres standing in the floodplain along the Battenkill, the dry husks crackling like paper when the wind went through. With no chance of getting it all in, he contracted the work to a French Canadian who was trailing the harvest south toward Pennsylvania. The Canadian cut the corn in a few days, starting each morning with a big skirting sweep that nearly touched the riverside cottonwoods. He didn’t seem too concerned about a job well done; when he left there was spilled corn all over the field, piles of it where the combine stopped to unload before coughing into gear again. The kernels sunk into the soft stubbled soil and then froze into resolute mounds. All manner of critters from crows to coons to whitetail deer came into the fields to scratch the leavings free, and waterfowl from well upstate piled in each morning like clockwork.

That December, Dave called on a Friday night to say that some weather was coming, and he’d seen ducks flying ahead of it. “Why don’t we plan for a morning at Paulson’s?” he said.

“I’ll have Bill join us too. Meet at my place at 4; I’ll bring my canoe and the Labrador… dress warm.” Then he added, “I know Bill’s your boss so don’t go shooting all his birds and pissing him off.” Truth was that Dave owned the company and was therefore Bill’s boss, and mine too, though that fact had always seemed to matter a little less when we went hunting. When Dave said such things, I never could tell if he was serious, or just good at picking out the threads of my insecurities.

Bill’s presence complicated things. He was a standup guy, but I was nervous around him, not so much because I was afraid he’d can me, but because I remained keenly aware that he could. He was quiet and circumspect, maybe sixty or so, and I had given up trying to impress him or ingratiate myself. When I had tried to do so early on, he’d just looked at me blankly as if wondering why I didn’t have better things to do. So, I kept my head down and did my work and assumed that if there was anything to read into Bill’s silence, I’d find out about it sooner or later.

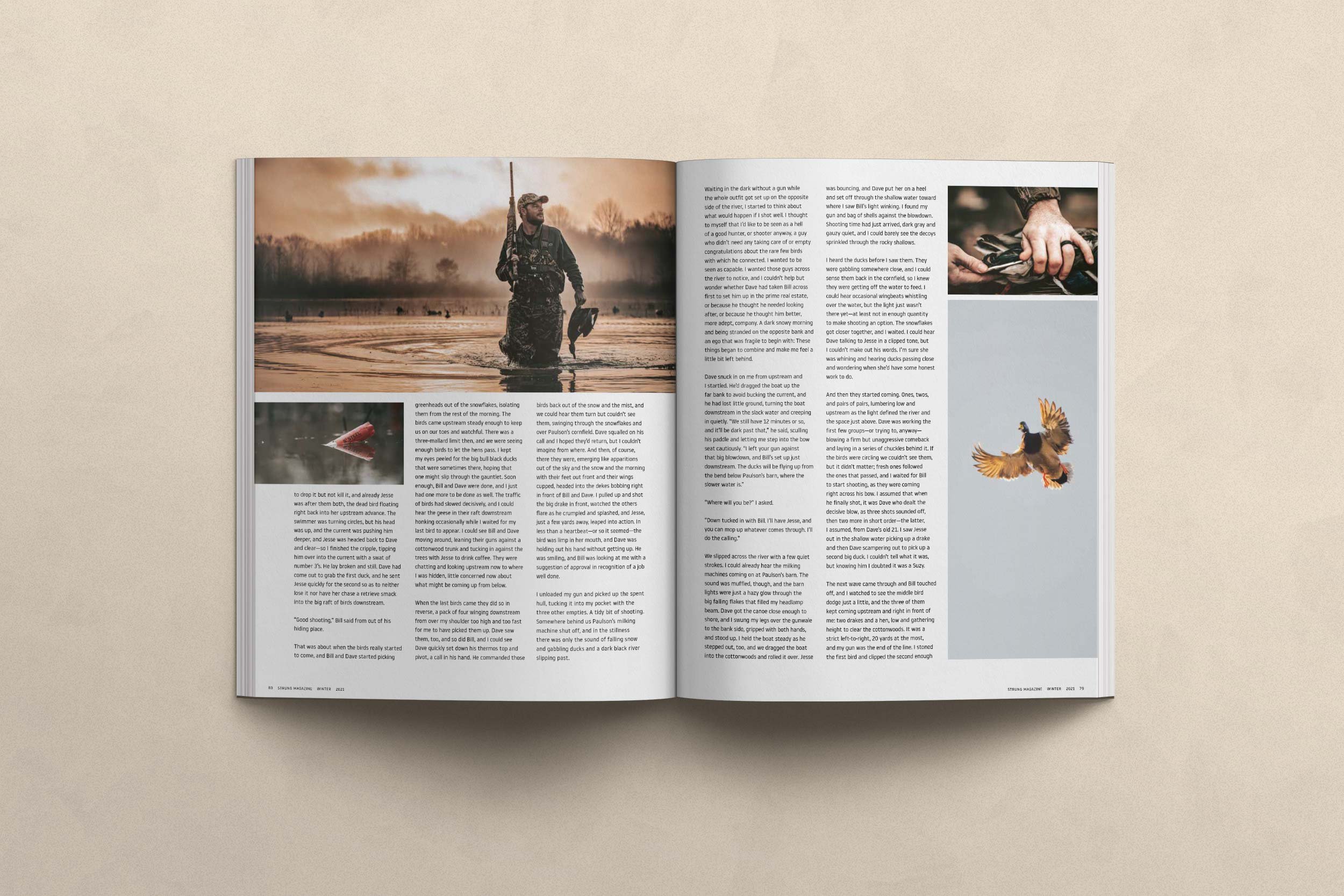

The morning wasn’t as cold as I’d figured it would be and the snow hadn’t started yet, but you could smell it coming. When I arrived, Dave and Bill were in the idling truck drinking coffee, the canoe already on the roof though it was still five till the hour. Their preparedness made me feel late and silly, so I apologized and chucked my gun and jacket in the back of the truck, squeezed into the rear seat next to Jesse the lab, whose tail thumped the upholstery. Dave’s headlights lit up cones of nighttime as he turned right out of his driveway and onto the tar road and began twisting through the dark towards the New York line. Dave and Bill hadn’t let my arrival interrupt their conversation, for which I was glad. It was about business, and how the year was fixing to end up. We drove along with them talking and me scratching Jesse behind the ears, and I felt comfortable being a little insignificant, so as not to sound uninformed. They didn’t ask my opinion anyway. Listening in and not being asked, I was starting to think that I’d like to impress both these guys, at least a little bit. I didn’t know anything about the business that they didn’t know better, but I did know there would be ducks, and we were out to shoot a few of them. I began to think that I’d really like to hit ‘em that day, to kill my limit clean and quickly and communicate that at this, anyway, I was wholly competent.

It was still quite dark when Dave pulled off the shoulder with the engine running and the low-beams on. We all got out. Bill and Dave untied the canoe, and I pulled the decoy bag and gun cases out of the back. Jesse disappeared over the shoulder and into the night, a black dog lost to the dark. A goose, closer than we could have known and clearly agitated, started honking, the sound starting low and guttural and culminating in that high, clear call that ends in a question mark. Dave left us to drag the gear down to the river, and he pulled away to stash the truck. He was always one for keeping things discreet… the good duck holes and trout pools and woodcock coverts, though he was just as keen to borrow the same from those less inclined to secrecy.

Bill and I loaded the canoe in a stiff silence, and the snow began to fall, big flakes that sifted through the cottonwoods and melted as soon as they touched. Dave came back along the water’s edge and pushed the canoe into the river until the current grabbed it and swung the bow downstream and against the bank. He held the boat by the gunwales to steady it, and whistled Jesse in.

“I’ll run Bill across and get the decoys set, and then I’ll come back and grab you.” He whispered this and held the boat for Bill, who stepped into the bow seat with more grace than I’d anticipated, and the two pushed off. That they had my gun with them didn’t matter, I supposed, since shooting light was still a piece off. I’d have liked it if Dave had noticed, though, in case the setup dragged on and the ducks started flying my way.

Waiting in the dark without a gun while the whole outfit got set up on the opposite side of the river, I started to think about what would happen if I shot well. I thought to myself that I’d like to be seen as a hell of a good hunter, or shooter anyway, a guy who didn’t need any taking care of, or empty congratulations about the rare few birds with which he connected. I wanted to be seen as capable. I wanted those guys across the river to notice, and I couldn’t help but wonder whether Dave had taken Bill across first to set him up in the prime real-estate, or because he thought he needed looking after, or because he thought him better, more adept, company. A dark snowy morning and being stranded on the opposite bank, and an ego that was fragile to begin with… those things began to combine and make me feel a little bit left behind.

Dave snuck in on me from upstream and I startled. He’d dragged the boat up the far bank to avid bucking the current, and he had lost little ground, turning the boat downstream in the slack water and creeping in quietly. “We still have 12 minutes or so and it’ll be dark past that,” he said, sculling his paddle and letting me step into the bow seat cautiously. “I left your gun against that big blowdown, and Bill’s set up just downstream. The ducks will be flying up from the bend below Paulson’s barn, where the slower water is.”

“Where will you be?” I asked.

“Down tucked in with Bill. I’ll have Jesse, and you can mop up whatever comes through. I’ll do the calling…”

We slipped across the river with a few quiet strokes. I could already hear the milking machines coming on at Paulson’s barn. The sound was muffled though, and the barn lights were just a hazy glow through the big falling flakes that filled my headlamp beam. Dave got the canoe close enough to shore and I swung my legs over the gunwale to the bank side, gripped with both hands, and stood up. I held the boat steady as he stepped out too, and we dragged the boat into the cottonwoods and rolled it over. Jesse was bouncing, and Dave put her on a heel and set off through the shallow water toward where I saw Bill’s light winking. I found my gun and bag of shells against the blowdown. Shooting time had just arrived, dark gray and gauzy quiet, and I could barely see the decoys sprinkled through the rocky shallows.

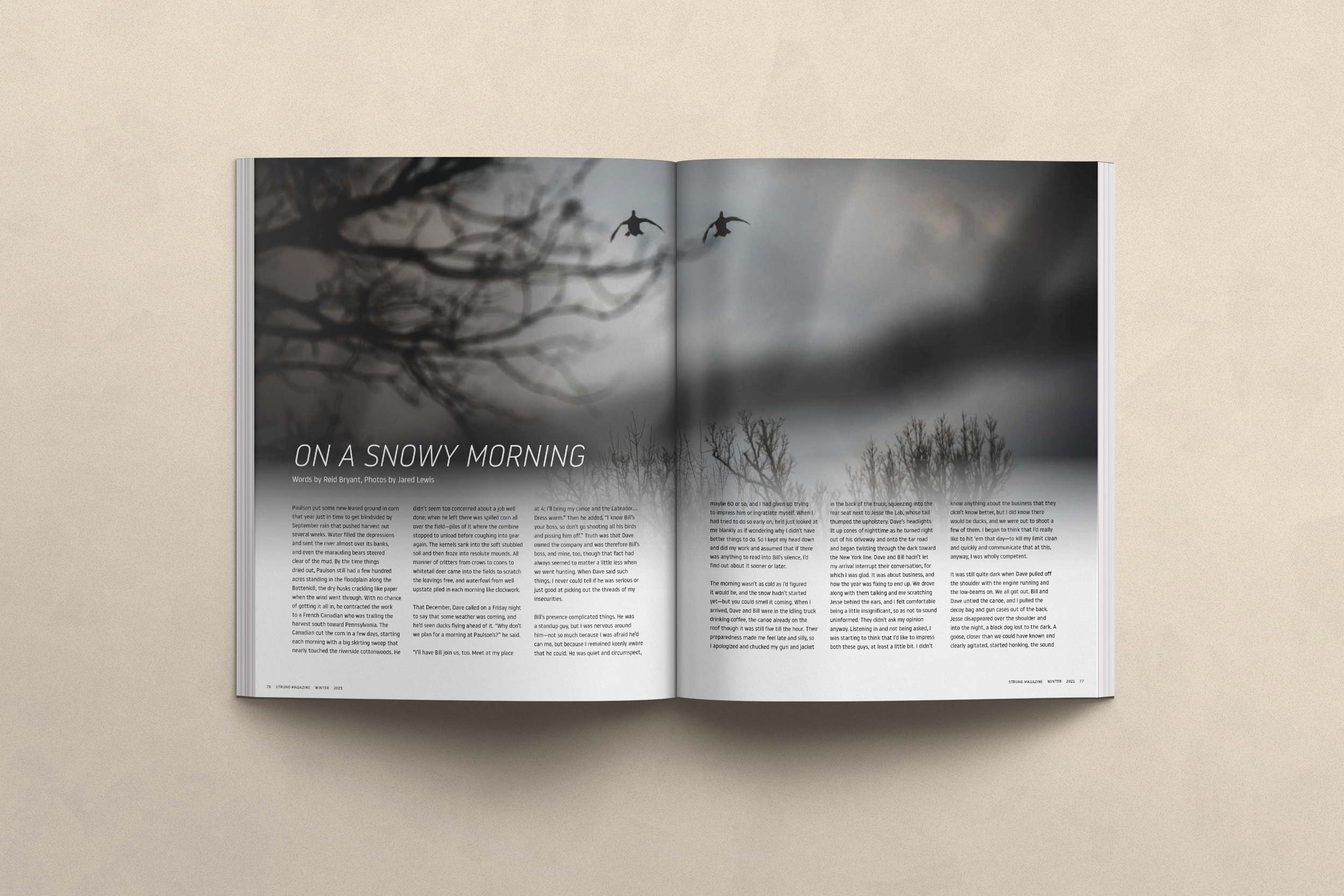

I heard the ducks before I saw them. They were gabbing somewhere close and I could sense them back in the cornfield, so I knew they were getting off the water to feed. I could hear occasional wingbeats whistling over the water, but the light just wasn’t there yet, at least not in enough quantity to make shooting an option. The snowflakes got closer together, and I waited. I could hear Dave talking to Jesse in a clipped tone, but I couldn’t make out his words. I’m sure she was whining and hearing ducks passing close and wondering when she’d have some honest work to do.

And then they started coming. One’s, two’s… pairs of pairs… lumbering low and upstream as the light defined the river and the space just above . Dave was working the first few groups, or trying anyway, blowing a firm but unaggressive comeback and laying in a series of chuckles behind it. If the birds were circling we couldn’t see them, but it didn’t matter; fresh ones followed the ones that passed, and I waited for Bill to start shooting, as they were coming right across his bow. I assumed that when he finally shot, it was Dave who dealt the decisive blow, as three shots sounded off, then two more in short order, the latter, I assumed, from Dave’s old 21. I saw Jesse out in the shallow water picking up a drake, and then Dave scampering out to pick up a second big duck. I couldn’t tell what it was, but knowing him I doubted it was a Suzy.

The next wave came through and Bill touched off and I watched to see the middle bird dodge just a little, and the three of them kept coming upstream and right in front of me, two drakes and a hen, low and gathering height to clear the cottonwoods. It was a strict left-to-right, twenty yards at the most, and my gun was the end of the line. I stoned the first bird and clipped the second enough to drop it but not kill it, and already Jesse was after them both, the dead bird floating right back into her upstream advance. The swimmer was turning circles, but his head was up, and the current was pushing him deeper and Jess was headed back to Dave and clear, so I finished the cripple, tipping him over into the current with a swat of 3’s. He lay broken and still. Dave had come out to grab the first duck, and he sent Jess quickly for the second, so as neither to lose it nor have her chase a retrieve smack into the big raft of birds downstream.

“Good shooting,” Bill said from out of his hiding place.

That was about when the birds really started to come, and Bill and Dave started picking greenheads out of the snowflakes, isolating them from the rest of the morning. The birds came upstream steady enough to keep us on our toes and watchful. There was a three-mallard limit then, and we were seeing enough birds to let the hens pass. I kept my eyes peeled for the big bull black ducks that were sometimes there, hoping that one might slip through the gauntlet. Soon enough, Bill and Dave were done, and I just had one more to be done as well. The traffic of birds had slowed decisively, and I could hear the geese in their raft downstream honking occasionally while I waited for my last bird to appear. I could see Bill and Dave moving around, leaning their guns against a cottonwood trunk and tucking in against the trees with Jesse to drink coffee. They were chatting and looking upstream now to where I was hidden, little concerned now about what might be coming up from below.

When the last birds came they did so in reverse, a pack of four winging downstream from over my shoulder too high and too fast for me to have picked them up. Dave saw them too, and so did Bill, and I could see Dave quickly set down his thermos top and pivot, a call in his hand. He commanded those birds back out of the snow and the mist and we could hear them turn but couldn’t see them, swinging through the snowflakes and over Paulson’s cornfield. Dave squalled on his call and I hoped they’d return, but I couldn’t imagine from where. And then, of course, there they were, emerging like apparitions out of the sky and the snow and the morning with their feet out front and their wings cupped, headed into the dekes bobbing right in front of Bill and Dave. I pulled up and shot the big drake in front, watched the others flare as he crumpled and splashed, and Jesse, just a few yards away, leaped into action. In less than a heartbeat, or so it seemed, the bird was limp in her mouth, and Dave was holding out his hand without getting up He was smiling, and Bill was looking at me with a suggestion of approval, in recognition of a job well done.

I unloaded my gun, and picked up the spent hull, tucking it into my pocket with the three other empties. A tidy bit of shooting. Somewhere behind us Paulson’s milking machine shut off, and in the stillness there was only the sound of falling snow and gabbling ducks and a dark black river slipping past.

First Published STRUNG Magazine