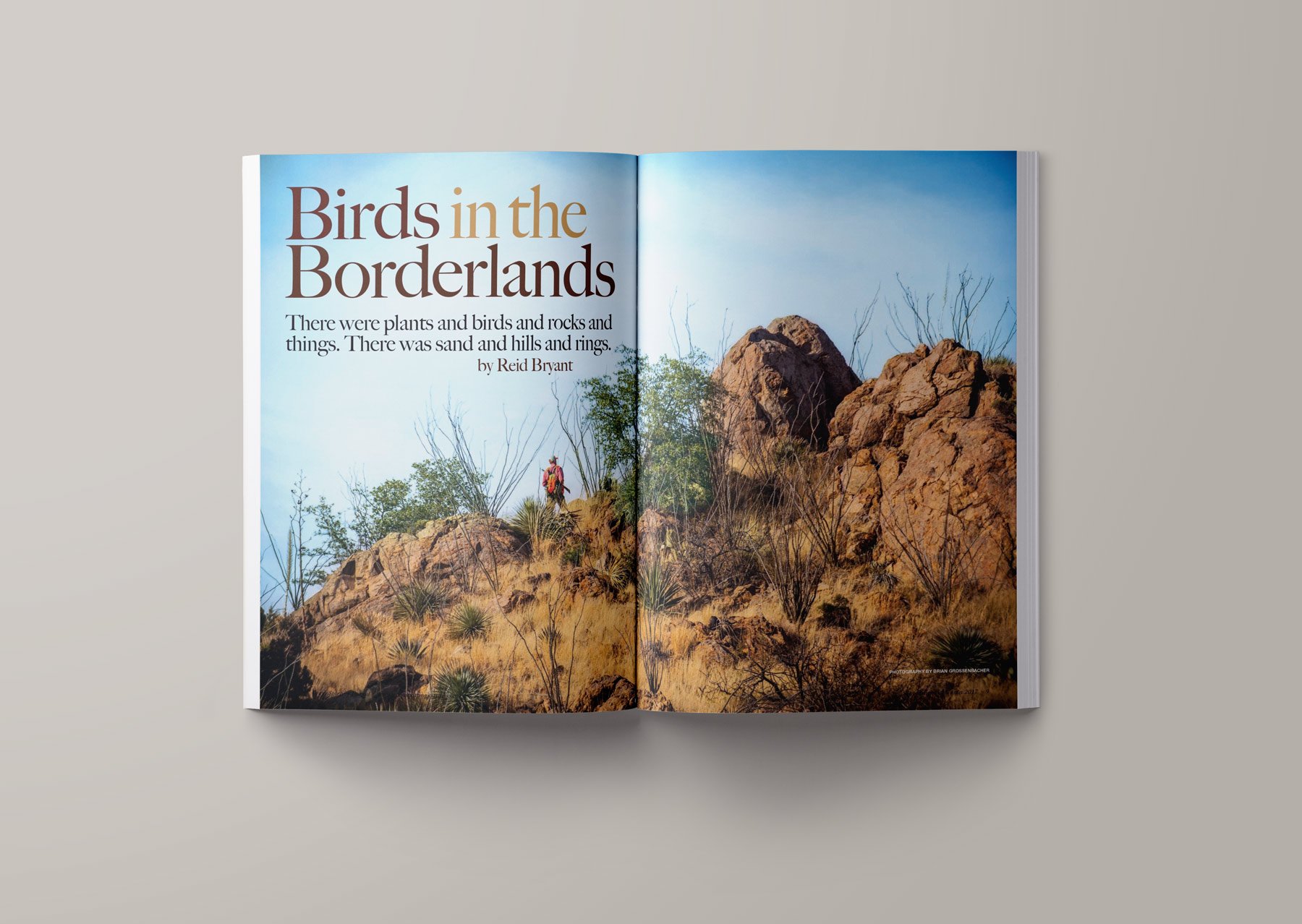

Birds in the Borderlands

If you were to stand where Cochise once stood, in the high saddles of the Chiricahua Mountains, you’d look out over a sweep of land that makes scale immaterial. Here the landscape grows so wide and spare that within it one can’t conceive of borders or the potential for man-made impediments. The scrub and grassland, the ocotillo and mesquite, become an indistinct mottling of straw browns and greens as dry and crinkly as shed snakeskin. This landscape goes on forever, and the horizon becomes a shimmering apparition more than a line of demarcation, barely decipherable at all. It’s hard to consider that somewhere in that arc of scrub desert, a barrier of corroded steel delineates two governments—being far simpler to take in the whole and consider this landscape as wide and uninterrupted as all eternity.

That said, standing there looking down into Mexico, you’d do yourself a disservice not to look a little closer. You’d do yourself a disservice not to view this land like Cochise once did, or like Aldo Leopold would have when he thought “like a mountain,” contemplating the interconnectedness of matters big and small.

Within that sweep of desert, within that jumble of mountains and grassland that straddles a border and holds up a sky, there occurs a remarkable marriage of ecosystems. Here, the Rocky Mountains of the north greet the Sierra Madre of the south, and the Chihuahuan Desert of the east meets the Sonoran of the west. The attendant flora and fauna co-mingle, and this confluence makes for some powerful stuff, both spiritually and ecologically. Its energy cannot be retained by a Normandy Barrier, and it renders the very concept of one laughable. Jaguars roam these borderlands, drifting north over international lines from the Central American jungles. Scaled, Gambel’s, and Mearns quail hustle back and forth across the hillsides, flushing from Mexico to the U.S. and back again. Mule deer and black bear and javelina follow ancient migratory paths, brushing against that iron fence, startling drug runners and coyotes whose disregard proves even more troublesome. This place mingles land and people and animals and climate into something that is not easily hemmed in. It is unlike anywhere else in the world.

Whether Josiah Austin considered these profundities when his love affair with the region began, it’s hard to say. Ask him, and he’ll think for a bit and respond, “No, the place just spoke to my heart.” But he did know that it was a beautiful and powerful country, and that the area ranches came cheap, as generations of cattlemen had grazed the place into a wasteland. It’s also safe to say that he couldn’t have known the impact he’d have on the region’s fate, or the impact it would have on his own as he shook off any thought of what could not be accomplished and simply saved something worth saving. What is clear is that the place speaks to Josiah, and it speaks to him loudest through quail.

On a January day, Josiah is standing just off the access road of the Bar Boot Ranch, one of the properties that he and his former wife, Valer, purchased and began restoring back in the mid-1980’s, amalgamating a vast portion of the desert southwest into an ecological success story under the umbrella of the Cuenca Los Ojos foundation. Over the past 35 years, what is now CLO has grown to maintain borderland properties in the U.S. and Mexico, with the sole purpose of restoring and preserving biodiversity, independent of international boundaries. This feat was accomplished most directly through water capture and a massive resource-management plan that reduces erosion and enables plant and animal regeneration. By allowing water to make a natural (i.e. slow) passage through the landscape and the ecosystem, erosive soils were retained alongside standing water. Couple these changes with an aggressive re-introduction of native species, and an eradication of invasives, and a place that had been recently mummified burst into life once more. The recurrence of native feed sources and water triggered a rebound in biodiversity. That meant quail and all that they represent, which makes Josiah Austin quite happy.

A tall and lanky man with a runner’s build, Josiah is dressed for the hunting day in a pair of faded jeans, a wide-brimmed hat, and his tattered shell vest. He’s nibbling on a dried grass stem, looking off dreamily to the west. There’s a skyline ridge there, a spine of contrasting green that makes the blue more radiant, but that is not what Josiah seems to see. He pulls the grass stem from his teeth.

“See the trincheras?” He sweeps a long arm over the landscape. “They’re the little earthen dikes that we’ve placed in the arroyos and washes, to hold back the rainwater and prevent erosion. I bet I can see a hundred of them just from here.”

I look hard but can’t see what he does. He smiles. “Look here,” he says, pointing closer. “There’s one right there, a small one. We call the small ones like that trincheras, but they are really just earthen berms. They fill the washes that runoff eroded when the native grasses were killed by overgrazing. True trincheras are made of stone. The bigger ones, the gabions, are wrapped in wire. You’ll see more of them tomorrow, on one of the other ranches. Over all the properties, I’d say we’ve built maybe 25,000. If anyone had told me that we’d be building 25,000 when I was just starting out, I’d likely never have built even one. ”I take a few steps closer, until I see what he sees. Nearly encased in dried grass, there is a small, stonework dam that spans a shallow arroyo. It’s barely waist high, not four feet across, but lovingly assembled of rocky soil. I walk over to it. The grass behind it is thick, though dead in the lateness of the season. The sand there is dust dry, and fine like talc.

“That’s the point,” says Josiah. “The silt doesn’t get washed out, it gets retained. That’s where the native grasses and sedges grow. It’s the bulbs of those that the Mearns eat.”

And indeed it is. We see the etchings of small digging feet in the silt behind the berm, and Josiah traces them with his grass stem.

“Lots of Mearns on this property. Let’s try to go find a few.” He flicks the grass stem away, naming it quietly in Latin, reverently, under his breath. It’s unclear whether this is for my edification or not. We load up regardless, and work our way deeper into the desert grassland that Josiah and the desert quail now share.

*

The idea of hunting quail along the Mexican border had been rattling around in my head for some time. It is likely that daydreaming was as far as the idea would have gotten had I not been friends with Dan Michels. Dan is another one of these fellows who doesn’t see impediments, and within weeks of floating an idea that I presumed was a non-starter, I got a call from Scottsdale. “We’re hunting with my friend Dave Brown. He’s guiding and running his dogs on a property called the El Coronado Ranch. If we’re lucky, the dogs will be quartering back and forth into Mexico to retrieve our birds. I’ll pick you up in Phoenix.” So naturally, as happens when a dreamer is at the wheel, it all fell perfectly into place.

We wended our way out of the Phoenix sprawl, driving into the January night, stopping once for a case of Modelo and a handful of Mexican limes, and again for a bowl of albóndigas soup in Benson to stave off the evening chill. Dan was wild-eyed and excited, having hunted the region with great success just a week earlier. I was taking comfort in the warm soup and cold beer, quietly hoping that we’d not wind up on the wrong side of a drug drop, and that our penchant for guns would not make us hostile combatants. With bellies full, we trundled back into Dan’s truck, and tooled deeper into a desert borderland whose mountains were backlit by stars.

This was country I’d visited years ago, in one of those bohemian quests for connection. I’d not hunted then, but climbed through the spires of the Dragoons and Chiricahuas absorbing what I could of Goyahkla’s Apache medicine through twig fires and nights spent under the Arizona sky. The bloodstained desert soils that comprise a life on the borderlands fill the region with a palpable mystery, and the expansive silences make it bigger.

We turned into Turkey Creek Canyon and rattled over the cattle guards. The canyon grew tighter by feel, and the air was cool and still. Several miles in, the lights of the ranch house flickered in between branches. We pulled into the dooryard. Perched above us was a glorious hacienda, illuminated inside and out, a beacon of warm welcome. It seemed the only human habitation for miles and miles. We hustled in. Dave and Josiah were there in a room filled with firelight and warmth. We gathered beside a massive hearth and made our introductions. To say that we felt welcome would be an understatement. We warmed ourselves by the fire and considered the days to come. Josiah poured bourbons. Dave laid out a plan.

In this region, Mearns quail are king. These glorious birds are found in intermittent patches of rolling desert along the Mexican border, often concurrent with Gambel’s and scaled quail, though the latter two prefer the bottomlands and places where standing water collects. In the eyes of a hunter, however, the species differ more significantly. Where Gambel’s and scalies run wild and bust, Mearns quail hold tight in grassland and scrub cover. For this reason, they are a pointing dog’s dream, erupting in coveys of ten or more birds that whizz off like bottle-rockets in a clatter of short-feathered wings. They are rare and beautiful, which in combination make a hunter’s heart beat faster. I’d never seen one in person, let alone held one warm in my hand. They’d become for me instead just another piece of the regional mystery, an emblem of that Apache medicine, a vestige of the Wild West.

Josiah refilled my drink and gestured me over to a glass-fronted bookcase. There on the shelves stood a mounted pair of each quail species, but the Mearns cock bird was the one Josiah pulled out. It was a rotund little bird that reminded me of an overdressed bobwhite, a jumble of striations and snow-white spots set against an iridescent black-brown undergarment. Some call it the Montezuma Quail. That night at El Coronado, Josiah just looked at it and smiled, not needing to give it a name at all.

*

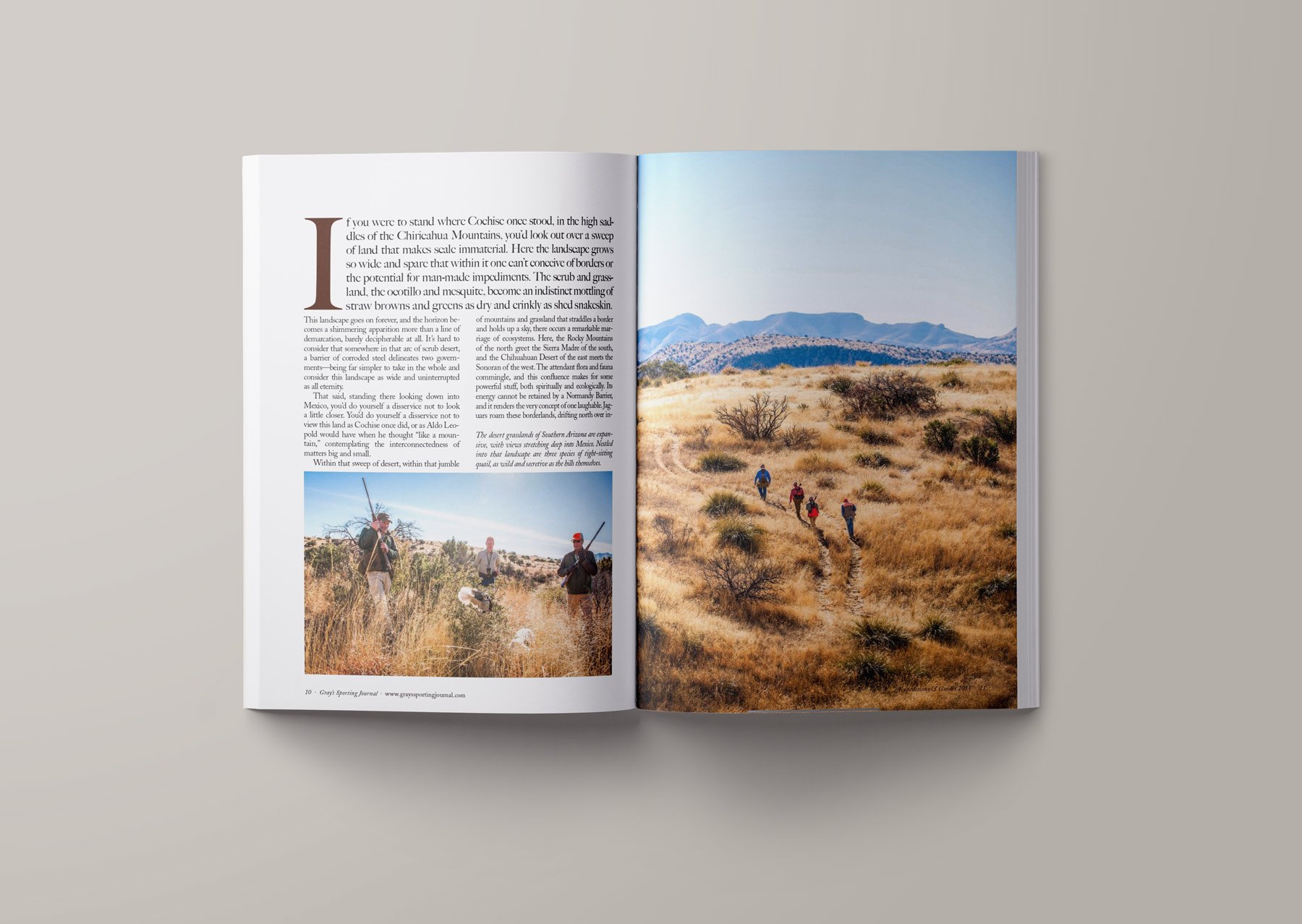

The next day at the Bar Boot, we drove deeper into the foothills and pulled off the track, aiming dog boxes away from the sun. Dave started hauling out dogs and putting his string together. Dave’s a Brittany man at heart, with some pointers thrown in for style, and he lugs his dogs two at a time with arms wrapped around their shoulders. He set the dogs down, collared and watered them, and turned them loose for a tour of the brush. All assembled, he looked at Josiah, who shrugged and smiled quietly. “I guess we work up this canyon, cross over the top, and work our way back down the canyon to the west.” We strung out three abreast, and eased over the grassy rise and into the arroyo to the east.

Dan took the side hill to the left, and I walked up the arroyo, while Josiah wove steadily up and down the hill to my right. The dogs bounced all around us as Dave watched them, smiling all the while. In the wash, I was able to study the trincheras more closely. At ground-level, these structures are still hard to see, as they’ve been so readily absorbed into the surroundings. Scrub grasses and sedge bristle around and over them. I found myself thinking of them less as a means of water capture, and more as an expression of desert folk art, as intricate and inconspicuous as any piece of old-world engineering. I saw Josiah stopping to inspect them too, bending over to feel the texture of the silt in the small side washes, commenting on the telltale scratch marks that meant the Mearns were near at hand.

The shallow canyon eventually petered out, and we lumbered out of it to gather on an oak-strewn rise. The day was glorious and cool as we caught our collective breath in the thick of it, feeling the exertion and the increased elevation. Mearns are not bottomland birds. They frequent hilly places, and I’d been told we’d be working for them. Josiah removed his hat, wiping his forehead on his sleeve. About then, Dave called out a dog on point.

There were actually two dogs on point, nose-to-nose, not ten yards apart. Dave’s little Brittany, Lucy, was honoring a few yards off, and my heart beat faster, though not from the climb. In deference to our host, I offered Josiah the first covey, but he wouldn’t have it. “You go,” he said, never closing his gun, and Dan and I moved in. I was ready for a flush, and a flurry of wings, but no part of me is ready for what greeted us. The world between the two dogs blew apart in fragments that buzzed with the fury of angry bees, erupting like a shower of sparks above, beside, and all around us. I poked desperately in one direction, swung and poked again, hearing Josiah’s gun sound to my right a split second after mine. A lone bird, tangential to the covey rise, tumbled into the sunburnt grass. When silence returned, a smiling Brittany was retrieving Dan’s bird, and I turned to Josiah to congratulate his fine shooting.

“No, no. That bird was all yours,” he said, as the pointer fetched it back. I was sure he was wrong but he insisted, and took the bird from Dave, then handed it to me. It will always be my first Mearns quail, given to me by a humble gentleman in a wide brimmed hat. I held it in my hand and marveled at its intricacy: the contrast of bars and spots and whites and blacks as precise and delicate as anything drawn in ink. I pocketed the bird. The remains of the covey had spread out across the hillside in scattered singles, and Dave looked over at Josiah for direction. “Enough to follow,” he said, affording us hope for a single or two without taking more than we ought from one covey. So we loaded our guns and followed the dogs, and crept ever deeper into the hillside.

That afternoon at the Bar Boot, we shot over a handful of unique Mearns coveys, taking thoughtfully and not wantonly, as if we had a choice. We filled our pockets with little mottled birds, interspersed here and there with a scalie or Gambel’s. But what I noticed, what I remember most, is the way that Josiah gave the hunt to us, and shared with us the wonder of that place. Dan and I walked up on each point at Josiah’s urging. Josiah offered up an occasional shot, but the quail seemed to mean far more to him than just shooting, and he’d just as often simply watch them scatter, smiling quietly to himself. I began to sense that quail were not the goal at all, but simply an indicator that a greater goal had been achieved.

Over the next few days, we hunted high and low, shooting, and often missing, three species. We ran dogs over, around, and through that magnificent country, letting them run as big as they could, confident that even a mile out, they’d barely be beyond our sight. We hunted ranches that pushed against Mexico, places with romantic, wild-west names like the old Smith Place, Cienaga, and El Coronado. We shot birds overlooking Turkey Creek, and the place where Doc Holliday ostensibly beat Johnny Ringo in a draw, and left his corpse beneath a shade tree. We stood in saddles where Cochise once stood, considering the interconnectedness of things.

All the while, I found myself watching Josiah. He’d hunt along with us, then fall back, drifting over the ridges and into arroyos where we’d find him kneeling, adding rocks to trincheras or pulling stalks of dried grass from the earth. He’d shoot and hit and in that reverential interlude between shot and retrieve I’d watch him sigh, and look beyond the quail-strewn cover before us, and into that sweep of landscape. He saw, I’m quite sure, something filled with possibility. All about him, the land was rebounding and proving itself in the scratched up silt that collected in the arroyos, and by little spotted birds that filled our game bags. He saw not a landscape, or a project broken up by impediments, or barriers, or “can’ts.” Instead he saw something bigger than himself, something timeless and priceless and utterly worth saving. Then he’d bend over to pick up a lime-sized rock and add it to the nearest trinchera, while 20-gauge shells dribbled out of the hole in his tattered vest pocket.

First published Gray's Sporting Journal