Insurance of Life and Livelihood

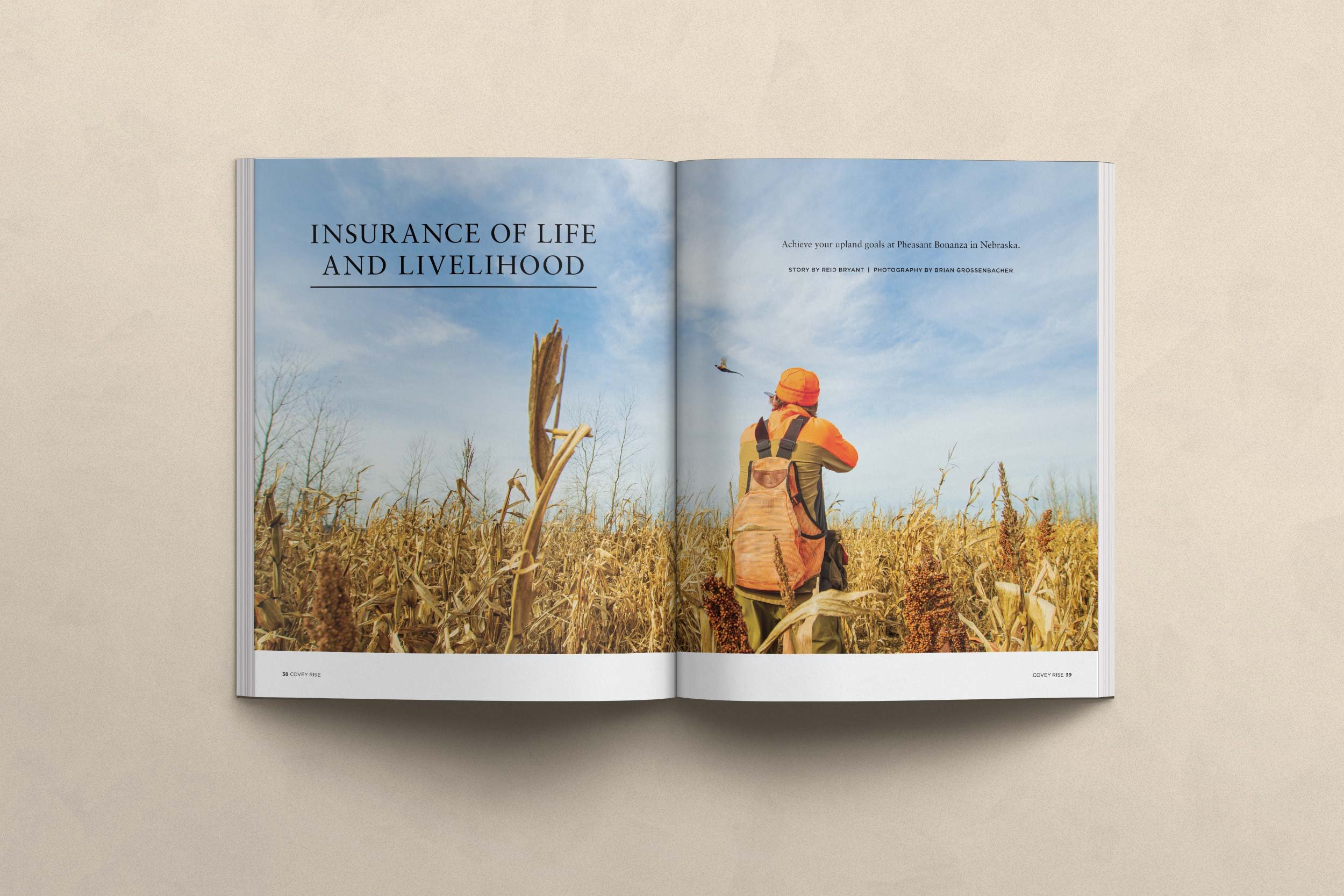

The truck makes a westward turn and begins the slow climb out of the bottom land. Behind us, a November morning is approaching noon, and combines are reducing the last standing corn to a study in progress and geometry. Despite the plumes of dust that attend the harvest, it’s a bluebird Nebraska day. It’s cold enough to make the colors - the browns and blues, and grey-green-golds - sharper than they’d otherwise be. The dog trailer we are hauling thumps over a bar ditch corner as we cut the turn, causing the occupants to bark a bit. The truck gears down for the climb.

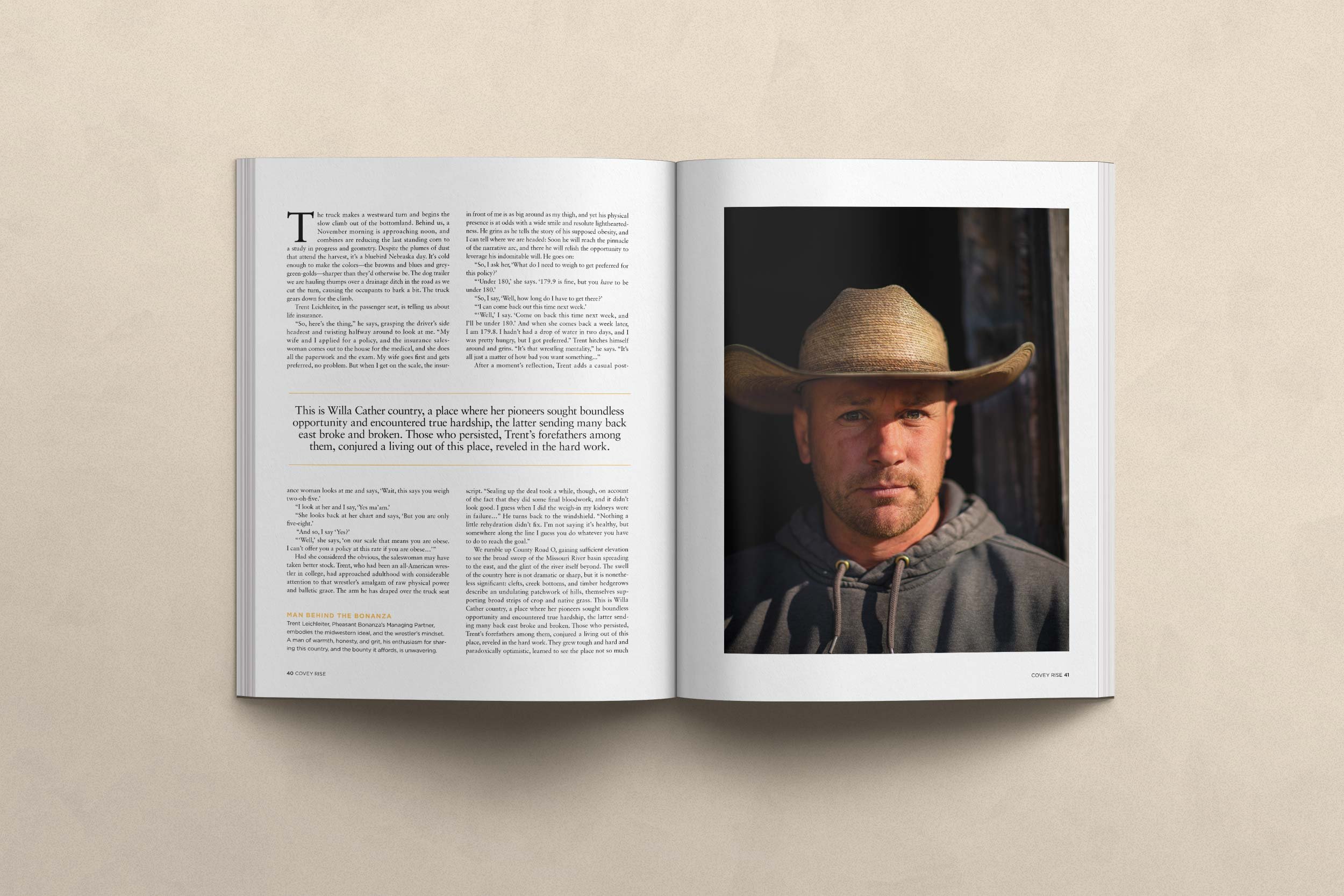

Trent Leichleiter, in the passenger seat, is telling us about life insurance.

“So, here’s the thing,” he says, grasping the driver’s side headrest and twisting half-way around to look at me. “My wife and I applied for a policy, and the insurance saleswoman comes out to the house for the medical, and she does all the paperwork and the exam. My wife goes first and gets preferred no problem. But when I get on the scale, the insurance woman looks at me and says, ‘Wait, this says you weigh two-oh-five.’

I look at her and I say, ‘Yes ma’am.’

She looks back at her chart and says, ‘But you are only five-eight.’

And so, I say ‘Yes?’

‘Well,’ she says, ‘on our scale that means you are obese. I can’t offer you a policy at this rate if you are obese…’

Had she considered the obvious, the saleswoman may have taken better stock. Trent, who had been an All-American wrestler in college, had approached adulthood with considerable attention to that wrestler’s amalgam of raw physical power and balletic grace. The arm he has draped over the truck seat in front of me is as big around as my thigh, and yet his physical presence is at odds with a wide smile and resolute lightheartedness. He grins as he tells the story of his supposed obesity, and I can tell where we are headed: soon he will reach the pinnacle of the narrative arc, and there he will relish the opportunity to leverage his indomitable will. He goes on:

“So, I ask her, ‘What do I need to weigh to get preferred for this policy?’

‘Under 180,’ she says. ‘179.9 is fine, but you have to be under 180.’

So, I say, ‘Well, how long do I have to get there?’

‘I can come back out this time next week’.

‘Well,’ I say. ‘Come on back this time next week and I’ll be under 180.’ And when she comes back a week later, I am 179.8. I hadn’t had a drop of water in two days, and I was pretty hungry, but I got preferred.” Trent hitches himself around and grins. “It’s that wrestling mentality,” he says. “It’s all just a matter of how bad you want something...”

After a moment’s reflection, Trent adds a casual post-script. “Sealing up the deal took a while, though, on account of the fact that they did some final bloodwork, and it didn’t look good. I guess when I did the weigh-in my kidneys were in failure…” He turns back to the windshield. “Nothing a little re-hydration didn’t fix. I’m not saying it’s healthy, but somewhere along the line I guess you do whatever you have to do to reach the goal.”

We rumble up County Road O, gaining sufficient elevation to see the broad sweep of the Missouri River basin spreading to the east, and the glint of the river itself beyond. The swell of the country here is not dramatic or sharp, but it is nonetheless significant: clefts, creek bottoms, and timber hedgerows describe an undulating patchwork of hills, themselves supporting broad strips of crop and native grass. This is Willa Cather country, a place where her pioneers sought boundless opportunity, and encountered true hardship, the latter sending many back east broke and broken. Those who persisted, Trent’s forefathers among them, conjured a living out of this place, reveled in the hard work. They grew tough and hard and paradoxically optimistic, learned to see the place not so much for its lonesomeness, but for its possibility. The challenge was a part of the reward. Maybe they had that wrestler’s mentality too, though their battles were a little less overt.

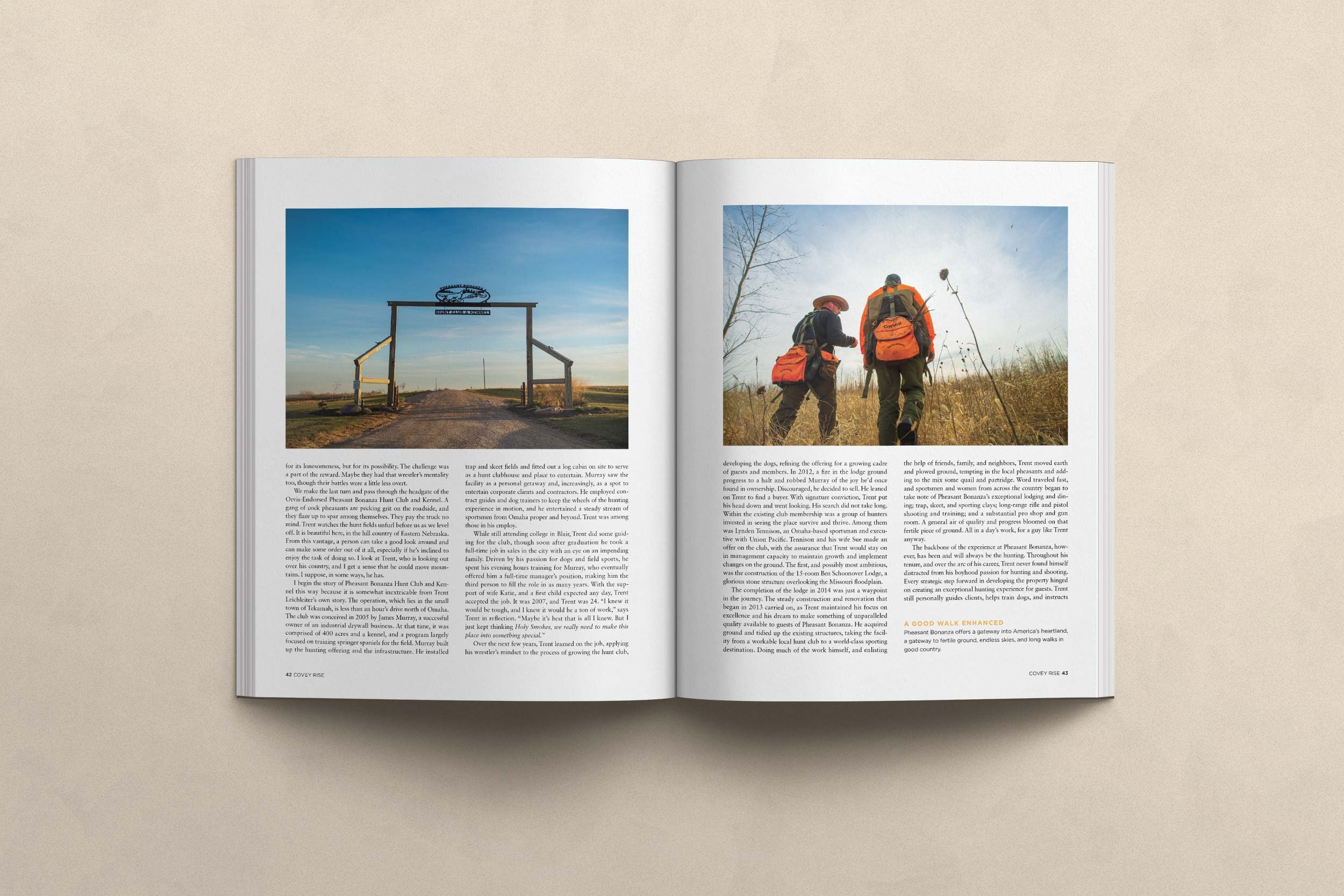

We make the last turn and pass through the headgate of the Orvis-Endorsed Pheasant Bonanza Hunt Club and Kennel. A gang of cock pheasants are pecking grit on the roadside, and they flare up to spar among themselves. They pay the truck no mind. Trent watches the hunt fields unfurl before us as we level off. It is beautiful here, in the hill country of eastern Nebraska. From this vantage a person can take a good look around, and can make some order out of it all, especially if he’s inclined to enjoy the task of doing so. I look at Trent, who is looking out over his country, and I get a sense that he could move mountains. I suppose, in some ways, he has.

I begin the story of Pheasant Bonanza Hunt Club and Kennel this way because it is somewhat inextricable from Trent Leichleiter’s own story. The operation, which lies in the small town of Tekamah, is less than an hour’s drive north of Omaha. The club was conceived in 2005 by James Murray, a successful owner of an industrial drywall business. At that time, it was comprised of 400 acres and a kennel, and a program largely focused on training springer spaniels for the field. Murray built up the hunting offering and the infrastructure. He installed trap and skeet fields, fitted out a log cabin on site to serve as a hunt clubhouse and place to entertain. Murray saw the facility as a personal getaway, and increasingly as a spot to entertain corporate clients and contractors. He employed contract guides and dog trainers to keep the wheels of the hunting experience in motion, and he entertained a steady stream of sportsmen from Omaha proper and beyond. Trent was among those in his employ.

While still attending college in Blair, Trent did some guiding for the club, though soon after graduation he took a full-time job in sales in the city with an eye on an impending family. Driven by his passion for dogs and field sports, he spent his evening hours training for Murray, who eventually offered him a full-time manager’s position, making him the third person to fill the role in as many years. With the support of wife Katie, and a first child expected any day, Trent accepted the job. It was 2007, and Trent was 24. “I knew it would be tough, and I knew it would be a ton of work,” says Leichleiter in reflection. “Maybe it’s best that is all I knew. But I just kept thinking ‘Holy Smokes, we really need to make this place into something special.’”

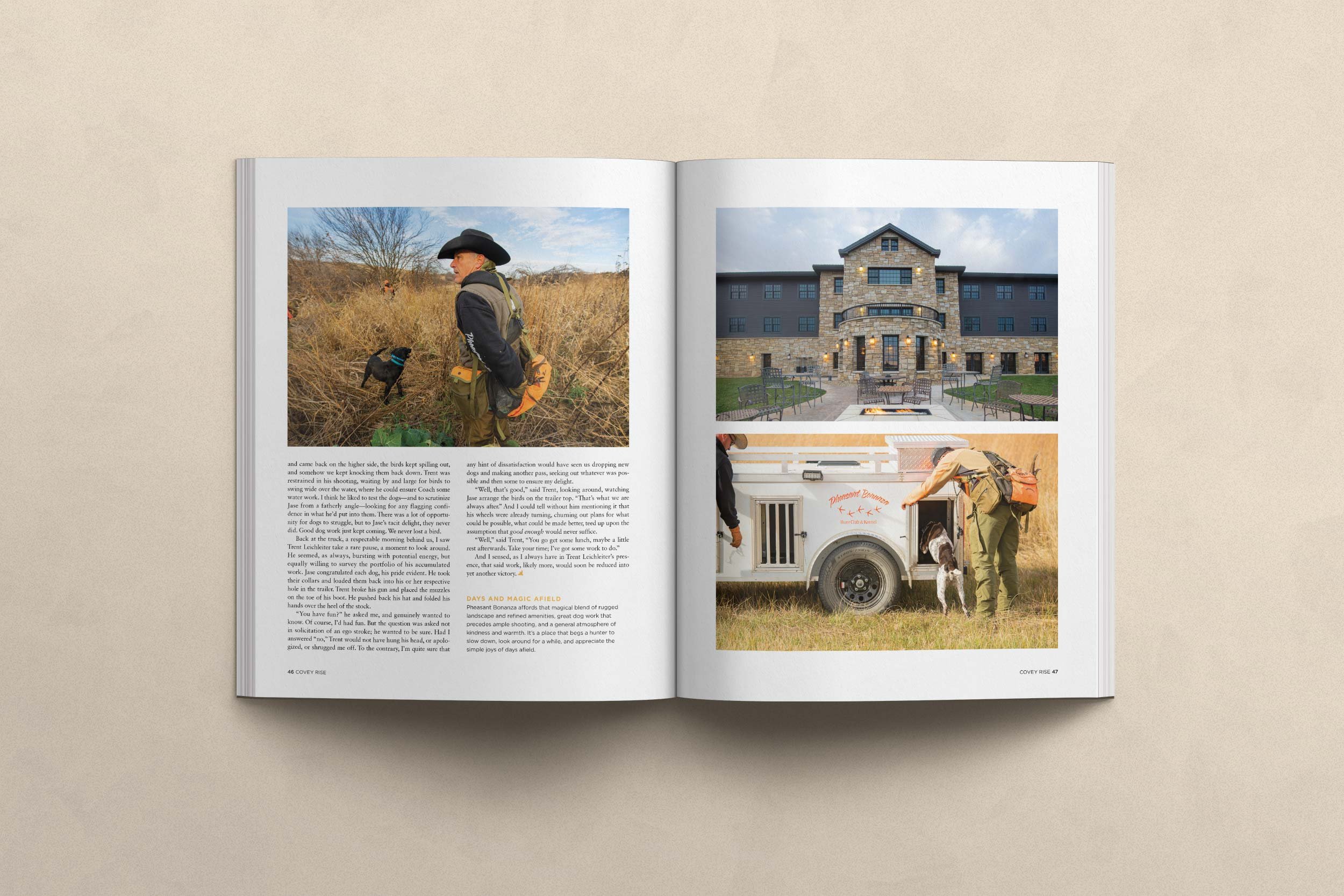

Over the next few years, Trent learned on the job, applying his wrestler’s mindset to the process of growing the hunt club, developing the dogs, refining the offering for a growing cadre of guests and members. In 2012, a fire in the lodge ground progress to a halt and robbed Murray of the joy he’d once found in ownership. Discouraged, he decided to sell. He leaned on Trent to find a buyer. With signature conviction, Leichleiter put his head down and went looking. His search did not take long. Within the existing club membership was a group of hunters invested in seeing the place survive and thrive. Among them was Lynden Tennison, an Omaha-based sportsman and executive with Union Pacific. Tennison and his wife Sue made an offer on the club, with the insurance that Trent would stay on in management capacity to maintain growth and implement changes on the ground. The first, and possibly most ambitious, was the construction of the 15-room Ben Schoonover Lodge, a glorious stone structure overlooking the Missouri floodplain.

The completion of the Lodge in 2014 was just a waypoint in the journey. The steady construction and renovation that began in 2013 carried on, as Leichleiter maintained his focus on excellence, and his dream to make something of unparalleled quality available to guests of Pheasant Bonanza. He acquired ground and tidied up the existing structures, taking the facility from a workable local hunt club to a world-class sporting destination. Doing much of the work himself, and enlisting the help of friends, family, and neighbors, Trent moved earth and plowed ground, tempting in the local pheasants, and adding to the mix some quail and partridge. Word travelled fast, and sportsmen and women from across the country began to take note of Pheasant Bonanza’s exceptional lodging and dining, trap, skeet, and sporting clays, long-range rifle and pistol shooting/training, and a substantial pro shop and gun room. A general air of quality and progress bloomed on that fertile piece of ground. All in a day’s work, for a guy like Leichleiter anyway.

The backbone of the experience at Pheasant Bonanza, however, has been and will always be the hunting. Throughout his tenure, and over the arc of his career, Trent never found himself distracted from his boyhood passion for hunting and shooting. Every strategic step forward in developing the property hinged on creating an exceptional hunting experience for guests. Trent still personally guides clients, helps train dogs, and instructs shooters in the disciplines of shotgun and pistol. He farms in the summer months, implementing a crop plan, burning, and planting CRP, native grasses, corn, milo, and sorghum. Currently, Pheasant Bonanza guests hunt on just under 6000 acres comprised of bottomland row crop, food plots, bands of grass, creek bottoms, and timber edges. There is terrain for every taste and temperament, several permanent pit blinds for waterfowlers to indulge in, and additional acreage for deer and turkey hunts. All told, it’s a remarkable composition of ground, one tended meticulously to hold birds in quantity, and to make their pursuit as exciting and aesthetically pleasing as possible. Given what Leichleiter has done with the place since 2007, its remarkable to think what the next 15 years could hold.

*

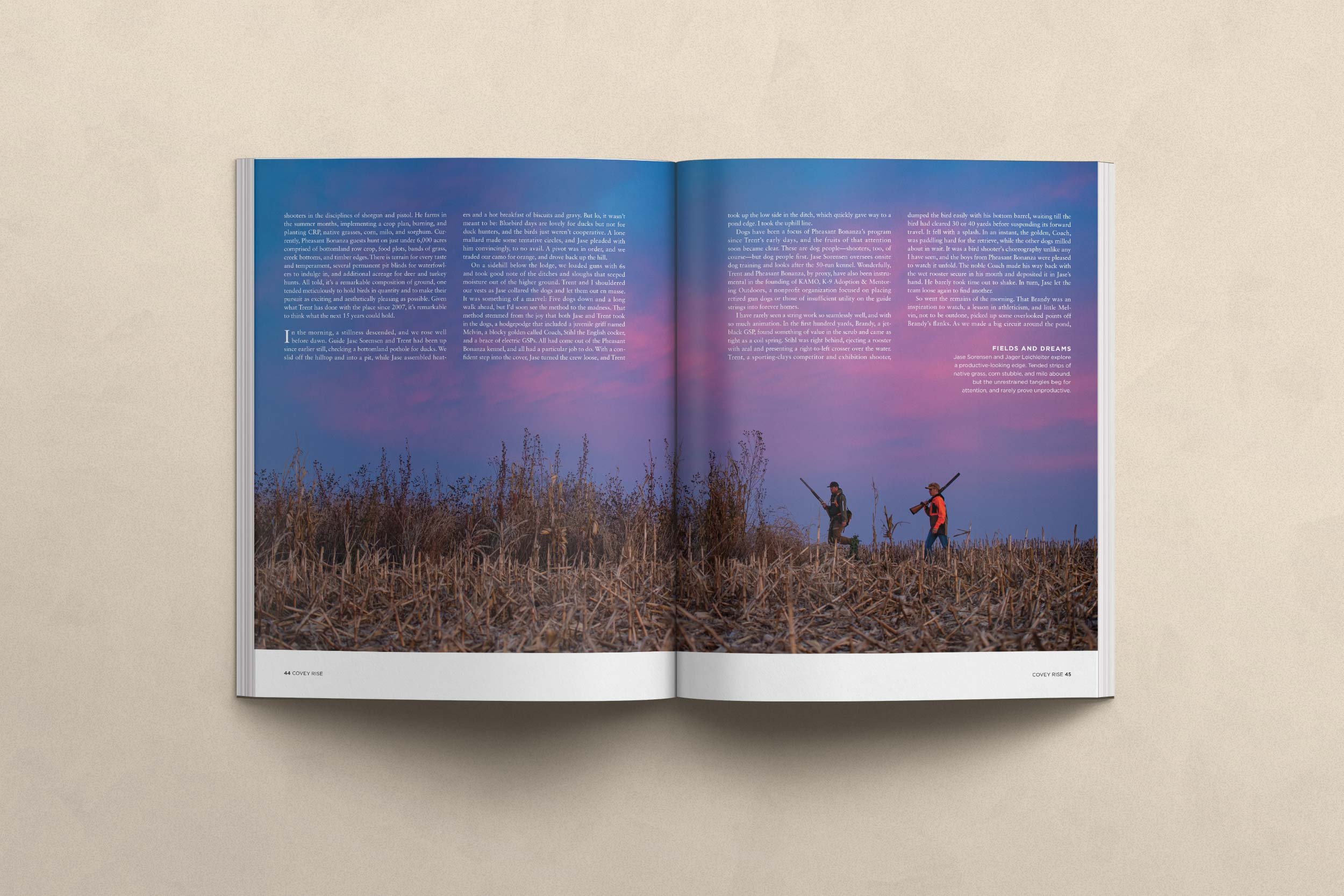

In the morning, a stillness descended, and we rose well before dawn. Guide Jase Sorensen and Trent had been up since earlier still, checking a bottom land pothole for ducks. We slid off the hilltop and into a pit, while Jase assembled heaters and a hot breakfast of biscuits and gravy. But lo, it wasn’t meant to be: bluebird days are lovely for ducks but not for duck hunters, and the birds just weren’t cooperative. A lone mallard made some tentative circles, and Jase pleaded with him convincingly, to no avail. A pivot was in order, and we traded our camo for orange, and drove back up the hill.

On a sidehill below the Lodge we loaded guns with 7.5’s and took good note of the ditches and sloughs that seeped moisture out of the higher ground. Trent and I shouldered our vests as Jase collared the dogs and let them out en masse. It was something of a marvel: 5 dogs down and a long walk ahead, but I’d soon see the method to the madness. That method stemmed from the joy that both Jase and Trent took in the dogs, a hodge-podge that included a juvenile Griff named Melvin, a blocky golden called Coach, Stihl the English cocker, and a brace of electric GSP’s. All had come out of the Pheasant Bonanza kennel, and all had a particular job to do. With a confident step into the cover, Jase turned the crew loose, and Trent took up the low side in the ditch, which quickly gave way to a pond edge. I took the uphill line.

Dogs have been a focus of Pheasant Bonanza’s program since Trent’s early days, and the fruits of that attention soon became clear. These are dog people, shooters too of course, but dog people first. Jase Sorensen oversees on-site dog training and looks after the 50-run kennel. Wonderfully, Leichleiter and Pheasant Bonanza by proxy have also been instrumental in the founding of KAMO, a non-profit organization focused on placing retired gundogs or those of insufficient utility on the guide strings into forever homes.

I have rarely seen a string work so seamlessly well, and with so much animation. In the first hundred yards, Brandy, a jet-black GSP, found something of value in the scrub, and came tight as a coil spring. Stihl was right behind, ejecting a rooster with zeal, and presenting a right-to-left crosser over the water. Trent, a sporting clays competitor and exhibition shooter, dumped the bird easily with his bottom barrel, waiting till the bird had cleared 30 or 40 yards before suspending its forward travel. It fell with a splash. In an instant, the golden, Coach, was paddling hard for the retrieve, while the other dogs milled about in wait. It was a bird shooter’s choreography unlike any I have seen, and the boys from Pheasant Bonanza were pleased to watch it unfold. The noble Coach made his way back with the wet rooster secure in his mouth and deposited it in Jase’s hand. He barely took time out to shake. In turn, Jase let the team loose again to find another.

So went the remains of the morning. That Brandy was an inspiration to watch, a lesson in athleticism, and little Melvin, not to be outdone, picked up some overlooked points off Brandy’s flanks. As we made a big circuit around the pond, and came back on the higher side, the birds kept spilling out, and somehow we kept knocking them back down. Trent was restrained in his shooting, waiting by and large for birds to swing wide over the water, where he could ensure Coach some water work. I think he liked to test the dogs, and to scrutinize Jase from a fatherly angle, looking for any flagging confidence in what he’d put into them. There was a lot of opportunity for dogs to struggle, but to Jase’s tacit delight, they never did. Good dog work just kept coming. We never lost a bird.

Back at the truck, a respectable morning behind us, I saw Trent Leichleiter take a rare pause, and a moment to look around. He seemed, as always, bursting with potential energy, but equally willing to survey the portfolio of his accumulated work. Jase congratulated each dog, his pride evident. He took their collars and loaded them back into his or her respective hole in the trailer. Trent broke his gun and placed the muzzles on the toe of his boot. He pushed back his hat, and folded his hands over the heel of the stock.

“You have fun?” he asked me, and genuinely wanted to know. Of course, I’d had fun. But the question was asked not in solicitation of an ego stroke; he wanted to be sure. Had I answered “no”, Trent would not have hung his head, or apologized, or shrugged me off. To the contrary, I’m quite sure that any hint of dissatisfaction would have seen us dropping new dogs and making another pass, seeking out whatever was possible and then some to ensure my delight.

“Well, that’s good,” said Trent, looking around, watching Jase arrange the birds on the trailer top. “That’s what we are always after.” And I could tell without him mentioning it that his wheels were already turning, churning out plans for what could be possible, what could be made better, teed up upon the assumption that good enough would never suffice.

“Well,” said Trent, “you go get some lunch, maybe a little rest afterwards. Take your time; I’ve got some work to do.”

And I sensed, as I always have in Trent Leichleiter’s presence, that said work, likely more, would soon be reduced into yet another victory.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine