Finishing a Gunstock Butt

A fine double gun is a marriage of form and function. When approached with a critical eye, nearly every detail on a fine gun is defensible. Each element either serves a purpose or served a purpose at a point during the evolution of the modern sporting shotgun. Nowhere is this concept more evident than in the shotgun butt, which may be finished in treatments that range from plain to wildly ornate. In each case, however, there is reason behind the plate, pad or checkered end-grain wood that composes the butt of the gun.

Let’s begin with some definitions. The “butt” or “butt-end” is the flat surface that is held against the shoulder when the gun is mounted, whereas the “buttstock” is the entirety of the wood that affixes to the action at the terminal end of the gun opposite the muzzles. The top of the butt-end, meaning the portion closest the shooter’s cheek, is known as the “heel”; the bottom of the butt-end nearest the shooter’s armpit is the “toe.” Note that despite variability in wood figure, the grain of the buttstock wood runs lengthwise, meaning that the butt-end is comprised of end grain, or the cut-off vascular fibers of the stock wood that carried water and nutrients up and down the live tree. As in any bundle of fibers, the strength of the buttstock lies in its ability to resist flexion up and down or laterally and its ability to resist compression end to end. The exposed ends of the fibers, however, are susceptible to chipping out—essentially becoming separated from one another—particularly at the vulnerable points of the heel and toe. And this is why gunmakers began covering butts in the first place.

Over time butt treatments have come to perform three vital functions. First, they allow the butt to meet the shooter’s shoulder in such a way that the butt slides naturally over clothing without catching yet provides enough friction to keep the mounted gun in place. Second, when and where possible, butt treatments provide some degree of recoil suppression or at least a sufficiently comfortable mounting surface to offset the discomfort of recoil. And third—and perhaps most notably—they provide some protection against stresses to the vulnerable heel and toe, which are prone to chipping, cracking or fractures due to the orientation of the wood grain.

Looking back in history, prior to the advent of breechloading guns, all guns were loaded through the muzzle. Muzzleloading guns were fed a load of powder and shot that was tamped into place with a ramrod, requiring the shooter to mash the load deep into the barrel to seat it against an unmoving surface. Physics required the butt, therefore, to be seated against a solid surface—typically the ground or the shooter’s foot—as the process of loading placed repeated impact against the vulnerable heel and toe. Many “poor boys,” or simple, inexpensive muzzleloading guns, lacked any reinforcement at the heel and toe that would mitigate chipping, which is why guns of that ilk that remain in existence commonly have ragged chips to the heel and toe. To remedy this problem, gunmakers began to reinforce the butt with a wrought-iron plate that would cover the exposed end grain and provide a durable surface to be placed on the ground when loading. These iron buttplates experienced refinement over time as gunmakers saw a canvas for ornamentation. Engraving and decorative metalwork enabled the early, clunky iron buttplates to become quite pretty and often incorporated a scored, stippled or lined surface that would seat securely against the shooter’s shoulder.

With the arrival of the breechloader, the need for a rugged buttplate was rendered moot. Simultaneously, advances in metallurgy made steel a lighter, thinner barrel material and enabled buttplates to be thinned and lightened to balance the gun. In an effort to reduce weight while still protecting the vulnerable edges of the butt from chipping, skeleton buttplates and specific heel and toe plates were employed. These treatments reduced weight, maintained a canvas for ornamentation and exposed end grain in the central portion of the butt that could be checkered for secure mounting. Though these treatments did little to mitigate recoil, they proved beautiful and functional, if somewhat costly to produce.

Recognizing that breechloading guns faced significantly fewer impacts to the butt than their predecessors, tastes and innovations in butt treatments turned gradually to focus more on secure gun mounting and recoil reduction. In an ongoing effort to solve for cost and weight and in acknowledgment that Edwardian-era gunners preferred a more austere, understated aesthetic, gunmakers began to employ simple buttplates of checkered hardwood or pressed Asiatic buffalo horn affixed with engraved screws. These treatments further allowed gunmakers to remove weight from the buttstock via lightening holes—voids that were in turn covered from view. More often, however, makers simply filed the hard edge off the butt and checkered the flat surface, plugging the lightening holes in such a way as to make them nearly invisible, and finishing the entire buttstock with oil or Slacum. The result was a clean, functional butt that did little to detract from the beauty of the wood itself.

By the later part of the 19th Century several innovations had arisen that would see ready use in the treatment of gun butts through the early 1900s. In 1839 Charles Goodyear serendipitously invented what would be known as vulcanized rubber, and in the 1880s Belgian chemist Leo Baekeland evolved his experiments with co-polymers to land in the early 1900s on a product called Bakelite, which would in effect be the first modern plastic. Moreover, in August 1874 H. Silver patented the rubber recoil pad, which proved a significant improvement over the stacked-leather and horsehair-stuffed “recoil pads” that had come before. As rubbers improved, soft pads by companies such as Pachmayr were introduced that could be easily covered in leather for a classy finish. All of these inventions not only lent a degree of recoil reduction to the treatment of the gun butt but also added the further value of branding to the gun. For the first time gun manufacturers could impress a name or logo into the gun butt, distinguishing their signature product with a monogram or image (as in Parker’s signature dog’s head) or simply by employing a noted, innovative product such as the Silver’s pad. As an added benefit, similar to the earlier plates, these treatments concealed not only lightening holes but also the drawbolt, or through-bolt, hole inherent on the increasingly common boxlock guns pervading the US market.

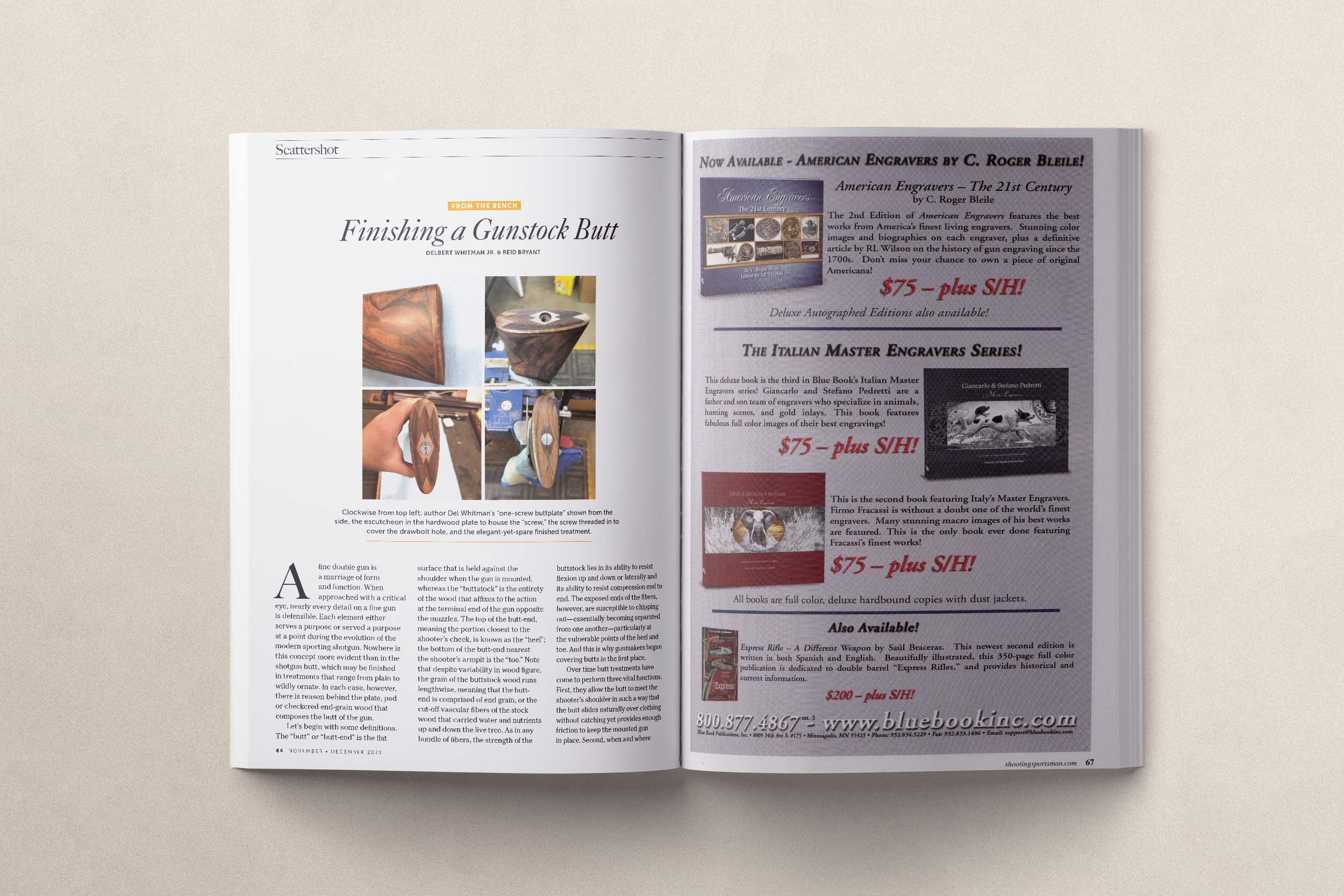

In the modern era butt treatments have seen clever innovations that showcase modern engineering and craft. Certainly there have been space-age recoil reducers of all shapes and sizes, many of which have gone in and out of vogue with changing aesthetic tastes. There have been more elegant refinements as well. Author Del Whitman has experimented with decorative plugs and screws that allow access to the drawbolt through a single, decorated screw head threaded into the center of the butt. In Del’s “one-screw buttplate,” a hardwood checkered buttplate is created and glued in place, but not before a threaded hardwood escutcheon or insert is integrated into the back side of the plate. A single, large-diameter “screw” is threaded into the escutcheon, covering a drawbolt hole that is large enough to receive the wrench required to remove the stock. The screw head provides a sizeable canvas to showcase elegant engraving, and the whole buttplate composes a piece of the gun that is elegant yet spare.

There are many ways to finish the end grain of the buttstock and to treat the butt in a manner that is both aesthetically pleasing and functional. With that, this look at butt treatments serves to shed light on the myriad ways that shotgun butts can and have been finished and the reasoning behind the treatments that have been employed.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine