On a November Morning

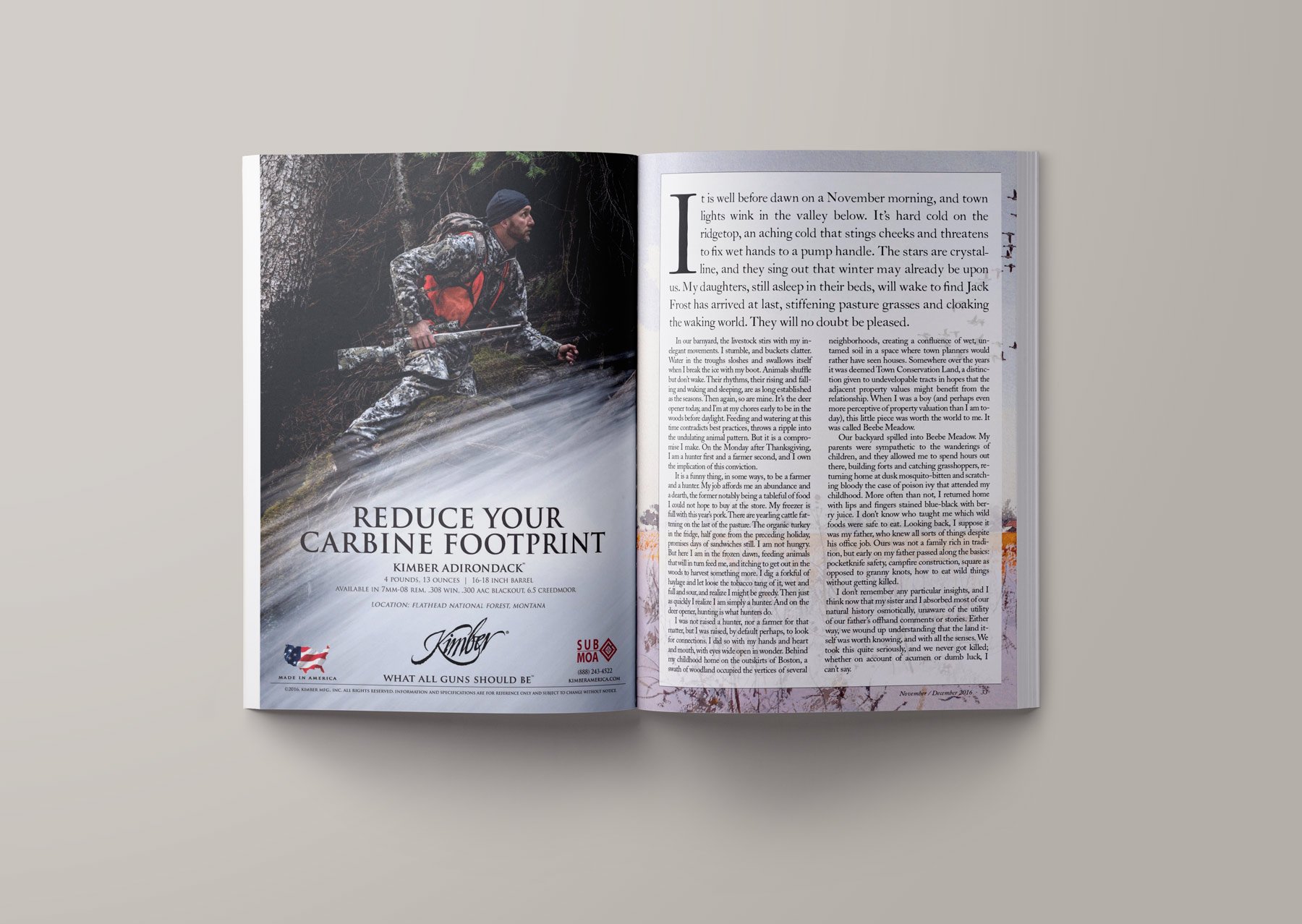

It is well before dawn on a November morning, and town lights wink in the valley below. It’s hard cold on the ridge top, an aching cold that stings cheeks and threatens to fix wet hands to a pump handle. The stars are crystalline, and they sing out that winter may already be upon us. My daughters, still asleep in their beds, will wake to find Jack Frost has arrived at last, stiffening pasture grasses and cloaking the waking world. They will no doubt be pleased.

In our barnyard, the livestock stirs with my inelegant movements. I stumble, and buckets clatter. Water in the troughs sloshes and swallows itself when I break the ream ice with my boot. Animals shuffle but don’t wake. Their rhythms, their rising and falling and waking and sleeping, are as long established as the seasons. Then again, so are mine. It’s the deer opener today, and I’m at my chores early to be in the woods before daylight. Feeding and watering at this time contradicts best practices, throws a ripple into the undulating animal pattern. But it is a compromise I make. On the Monday after Thanksgiving, I am a hunter first and a farmer second, and I own the implication of this conviction.

It is a funny thing, in some ways, to be a farmer and a hunter. My job affords me an abundance and a dearth, the former notably being a tableful of food I could not hope to buy at the store. My freezer is full with this year’s pork. There are yearling cattle fattening on the last of the pasture. The organic turkey in the fridge, half gone from the preceding holiday, promises days of sandwiches still. I am not hungry. But here I am in the frozen dawn, feeding animals that will in turn feed me, and itching to get out in the woods to harvest something more. I dig a forkful of haylage and let loose the tobacco tang of it, wet and full and sour, and realize I might be greedy. Then just as quickly I realize I am simply a hunter. And on the deer opener, hunting is what hunters do.I was not raised a hunter, nor a farmer for that matter, but I was raised, by default perhaps, to look for connections. I did so with my hands and heart and mouth, with eyes wide open in wonder. Behind my childhood home on the outskirts of Boston, a swath of woodland occupied the vertices of several neighborhoods, creating a confluence of wet, untamed soil in a space where town planners would have rather seen houses. Somewhere over the years it was deemed Town Conservation Land, a distinction given to undevelopable tracts in hopes that the adjacent property values might benefit from the relationship. When I was a boy (and perhaps even more perceptive of property valuation than I am today), this little piece was worth the world to me. It was called Beebe Meadow.

Our backyard spilled into Beebe Meadow. My parents were sympathetic to the wanderings of children, and they allowed me to spend hours out there, building forts and catching grasshoppers, returning home at dusk mosquito-bitten and scratching bloody the case of poison ivy that attended my childhood. More often than not, I returned home with lips and fingers stained blue-black with berry juice. I don’t know who taught me which wild foods were safe to eat. Looking back, I suppose it was my father, who knew all sorts of things despite his office job. Ours was not a family rich in tradition, but early on my father passed along the basics: pocketknife safety, campfire construction, Square as opposed to Granny knots, how to eat wild things without getting killed.

I don’t remember any particular insights, and I think now that my sister and I absorbed most of our natural history osmotically, unaware of the utility of our father’s offhand comments or stories. Either way, we wound up understanding that the land itself was worth knowing, and with all of the senses. We took this quite seriously, and we never got killed; whether on account of acumen or dumb luck, I can’t say.

Wandering Beebe Meadow through all of the seasons, we ate wild strawberries so tiny and sweet they almost made us sad. We ate raspberries too ripe to withstand the picking, wild mint through the August heat, and plump blackberries when the school year loomed close. We ate wild carrots dug with dirty fingers, and the sour wood sorrel that bloomed in quiet, shady places. We milked honeysuckle blossoms by the score, letting each droplet of exquisite sweetness dance on the tip of our tongues.

I was not an overly poetic child, but I understood somehow that in eating the foods of Beebe Meadow, I was sinking deeper into it, becoming a part of the place and the seasons. In and with every sense, I gave flesh to my place by tasting it, thereby understanding it more fully. Which led me, inevitably, to hunting.

*

In the autumn mornings of my early childhood, I would occasionally wake to gunshots in Beebe Meadow. I knew the sound, knew about the men in wool shirts and hip-boots who hunted ducks and pheasants out there while I lay in bed. I’d seen them loading dogs and guns into cars, and I in turn had hunted their discarded shot shells, making treasures of them, so rare were they to me. Hunters in my neighborhood were rarer still, old-fashioned seeming and essentially of New England. I did not speak to these men, nor often even see them, but unlike my sister, who was horrified at the piles of bloody feathers, I was captivated by them. I understood. The flesh of the land, sliced from its breast in the rising light of an autumn day; what greater intimacy could there be?

I realize now, and I’m unashamed to admit, that my desire for connection required a heartbeat receding, required flesh and blood and something held in the hand more elusive than a blackberry, or a sprig of wild mint, or a summer day. Many traditions, spiritual and cultural, imply that we have in each of us a soul, a purest essential fabric, a psycho-spiritual-social DNA that we bring with us into the world, and leave with, too. In mine there is hunting. I knew it then, and I know it now. But well into my adulthood hunting was something reserved for old men in wool shirts, with bird dogs and double guns and sweet smelling tobacco, men remote to me. So, for longer than I care to admit, I simply padded behind them, built elaborate reconstructions of their early mornings, plucked their shot shells from the mud. And I wondered, lying in bed, how I would ever learn to hunt.

It turned out that this wondering charted my course, if only because those things essential to each of us are at some point inevitably revealed. I did not have a hunting father, or a gun-loving mother, or a community steeped in sporting tradition. The last morning volley wakened Beebe Meadow before I was eight, so I didn’t even have working models for my dreams. Instead, I read stories of hunters, looked at their magazines, learned the game trails they traveled. I wound up in college in a remote New England town where hunting was as much a part of the social fabric as town meetings, where ammunition stood stacked beside pouches of Red Man and Beechnut at the general store. I came to the world of hunters dogged and unabashed, stumbling square into its fraternal order with my ego on the shelf. I took hunter’s safety classes with 10-year-old children, and begged anyone who’d listen to let me follow them into the woods. Not many did. But hunting requires more than a book, more than an offhand lesson, and though it remains etched into our very humanness, it requires today more than just that osmotic understanding. So I asked, and asked, and was patient. Perhaps they did it to end my pestering, but there were a couple of long-suffering souls, friends now, who opened the door just a crack. I walked behind and eventually beside them, and they taught me to move in silence borne of reverence and necessity, to kill things and be sad and fulfilled by the same token. In the end, there was food—fundamentally wild and good.

I’ve eaten grouse and woodcock and duck, rabbit and venison and hare. Each I’ve seen alive against a palate of native color, against a splotch of season and landscape and time. Each I’ve killed and thanked, and witnessed its transformation from animate majesty to meat and fur and feather and gristly bone. I won’t argue whether this is right or wrong. It is what I’ve done, and what I have admittedly wished to do. I’ve grilled venison loin blood-rare inside and charred out, simmered rabbit quarters in wine for hours, made duck ragout with orange zest and fresh pasta. In each forkful, nestled amidst the herbs and salt and butter and Tellicherry pepper, there has always been something honest. Some flavor, some hint, some essence of a moment that was not pen-raised, or pre-destined for the slaughterhouse. Others eat game for the leanness of it, for the local source, for the free-range/pastured/organic integrity of the meat. I like it for the honesty. I went looking, and I took something as pure as the falling leaves, owned its demise and felt its life fading, and made it a part of me.

*

On a frostbit morning, the chores are done an hour before daylight. I’ll eat my eggs and bacon, build a fire in my belly to stave off the cold, and walk into the woods to look for something essential. Mine is a life on the land, a life patterned by food and chores and cold early mornings. It is an honest life in itself, a life that hardens my hands and illuminates the passage of days with sunrises and sunsets. It is a life of chapped cheeks and pocketknives carried out of necessity, and some days that is enough. Other days, like the Monday following Thanksgiving, I need more.

Sometimes I find it in the flesh and blood and bone of the land. I get there, return there, through hunting. Not killing, but hunting: looking hard for something both elusive and pervasive, something available to us each as part of the earthly package. It is our common wealth. For me, wild meat and a stump seat for the aria of a November sunrise are my connection to the land that sustains us. In a plastic-wrapped, flash-frozen, and increasingly distant world, we all find it where we can.

First published Gray's Sporting Journal