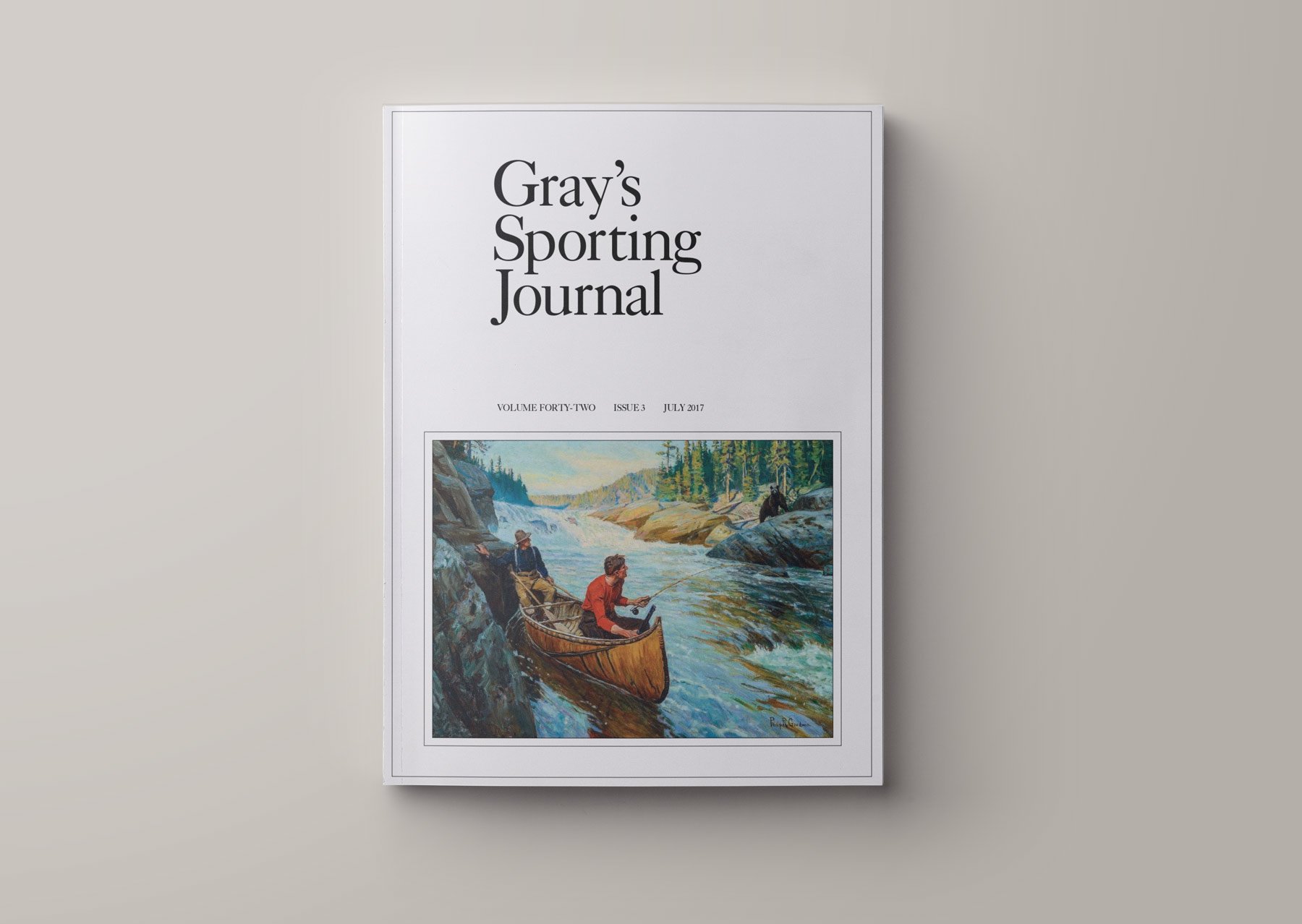

On the Other Side of Reason

6 AM on Saturday I’m en route to western Russia in pursuit of Atlantic salmon. Among fly fishers, an Atlantic salmon is the rarest of jewels, and more than one poor soul has lost a fortune in pursuit of the leaping fish. I never took Atlantics seriously, as I long assumed that I’d never gain admission to the places where they are caught; salmon rivers are closely-held, and they flow beneath a haze of smoke and mirrors. And even if I managed my way onto some water, Salmo salar, like most anadromous fish, refuse to eat upon entering their spawning cycle. This poses a serious obstacle to the match-the-hatch fly-fisher, and results in the not-uncommon fishless week. Though I’m not what you’d call fiscally responsible, I’ve never felt duty-bound to throw a few months’ salary at a week of not catching fish. So I satisfied myself with palm-sized brook trout, and opined that anyone who declared himself an Atlantic salmon angler was probably a self-indulgent asshole anyway. And then… wouldn’t you know it? I got a chance to go.

In college, Matt Breuer and I fished together… a lot. Much to the chagrin of our respective parents, Breuer and I managed to graduate with an encyclopedic knowledge of the local freestones, and no clear aspiration for adulthood. I fell upon odd jobs that afforded me fishing around the edges of the day, and Breuer, ever the pragmatist, made fly fishing a career. By his thirties, he was managing a camp on the Kola Peninsula’s Ponoi River where, in a sport celebrated for a dearth of fish, several salmon per day remains the norm. A balance of inaccessibility, protection, and cultish secrecy allow Ponoi salmon stocks to flourish, and it takes big money and some serious social collateral just to get there. My friend Breuer was sitting on an Ace, and, confident that fishing buddies take care of their own, he kicked a trip my way. It must be too good to be true.

12 PM on Saturday The rotors of the Mi8 helicopter roar and rattle down through the cabin. From a thousand feet up, the Kola Peninsula resembles a green sponge, too full of water to absorb any more. The excess runs over, and settles in the dimples, which show blue-black and bottomless. Early in the arctic day, mist sifts through the cloudberry and lichen, drifting over rivers that spread to the White and Barents seas. The softness of the landscape is reassuring, and the crew mechanic has fallen asleep. Across from me, Heidi Andrews is fiddling with her necklace. Her eyes are closed. I choose to interpret her attitude as calm, and I let myself be lulled by the “whunka whunka” of the rotor. I turn back to the wash of emptiness, and am amazed that the terrain is beautifully simple. The thin air illuminates a landscape so immaculate that I’m suddenly a little more hopeful than a nervous guy in a military-surplus helicopter should be. I look over and smile at Carter, Heidi’s husband. He rolls his eyes and flashes 2 fingers on his left hand: two more hours. I turn to my window and rest my head against the cowling.

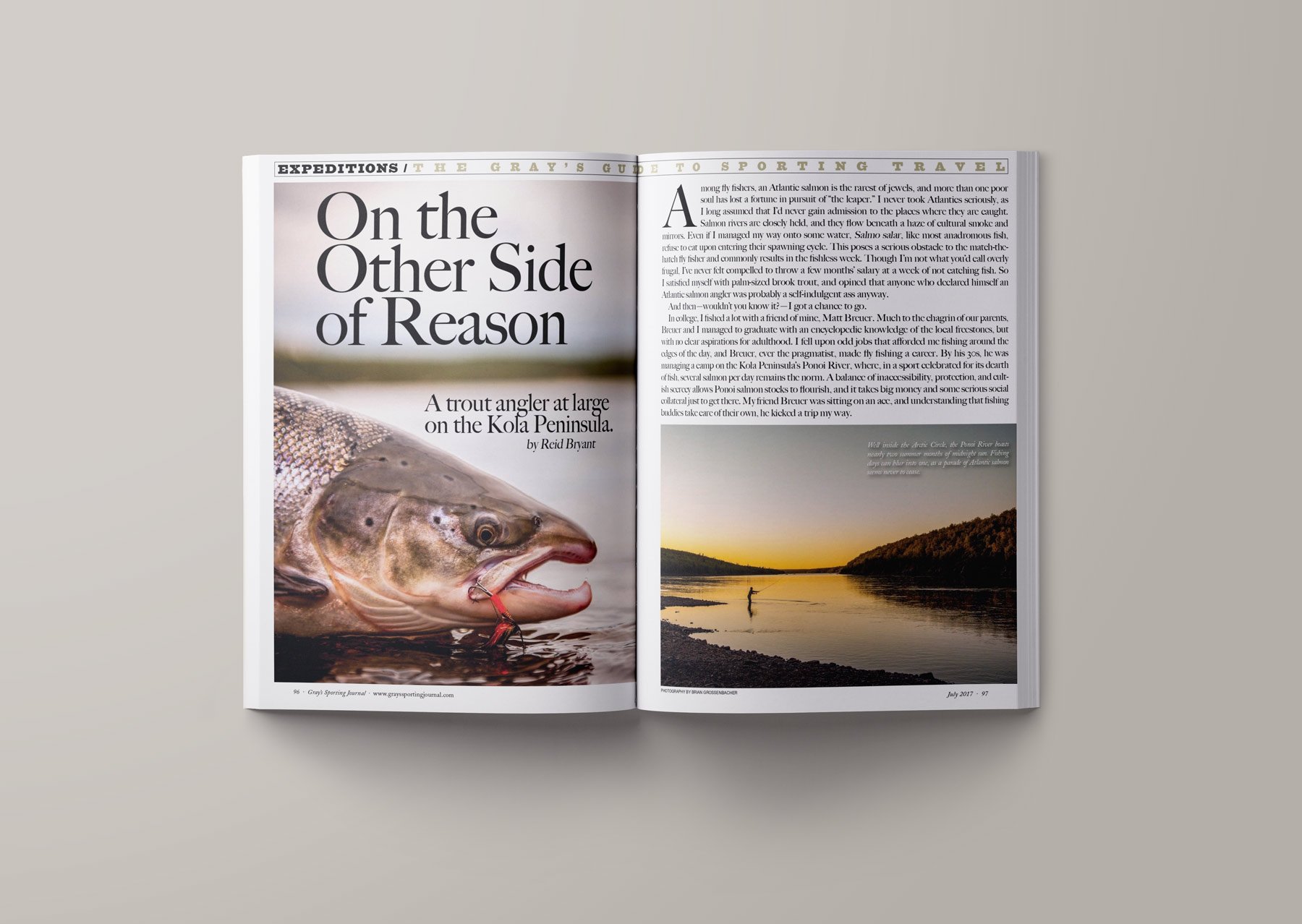

The Atlantic salmon is an enigma. It is hatched in the rivers of the North Atlantic drainage, and it grows, over a period of years, into a scrappy, trout-like fish. At length, the young salmon departs the river and enters the salt. In the waters of the Atlantic, the young salmon grows fat on baitfish and shrimp. It gains its chops eluding seals and whales and trolling hooks, all of which have designs for the salmon’s flesh. Eventually, a primordial trigger beckons the now-mature salmon back to its natal river in a journey of procreation. And then, having survived a subdued adolescence, the spawning salmon lets its freak flag fly. Upon re-entering the river, the Atlantic salmon is fighting trim, even as a first-timer (grilse) it boasts glittering flanks flecked in black. In acclimating to the fresh water, the “bright fish” ceases eating, and it maintains this attitude throughout the duration of the spawn, which can last up to 18 months, after which it descends once more to the sea. The physical metamorphosis of the spawning fish is profound; silver fades into a burnt-butter-brown, and the flecking is replaced with haloed red spots. You’d assume that, in the absence of nourishment, the salmon would maintain a low profile, focusing entirely on self-preservation, but this fresh water period seems the most costly for the fish in terms of energy. Somewhere amidst the characteristic leaping and cart-wheeling, the salmon becomes aggressive and territorial; the depleted fish, played out from spawning, barely resists the temptation of slaughtering anything remotely incandescent that passes before its nose… all of this, while growing snakey and hook-jawed, barely capable of a return to the sea. 18 months in they are ‘dark’ and reptilian, but played-out or not, they descend, fatten and brighten again in the salt, and re-enter the river to repeat the process again and again.

The cadence of the motor shifts subtly. It goes deeper, and the mechanic is awake and looking into the cockpit. Carter’s eyes are concerned. We’re either in descent to camp, or going down the bad way. I scan the passengers. They all appear too important to be lost in a helicopter crash. I assume my salvation based on association, and look forward to being on land. I think I see Matt Breuer down there on the pad.

5 PM on Saturday We follow the steps down from the tundra and enter the Ryabaga Camp Big Tent, where a fire is blazing in the stove. Camp staff hustle about, stowing duffel in the sleeping tents, bringing out platters of reindeer salami and salmon sashimi. One guest, a Brit, sinks into the couch beside the fire, and waggles a stubby finger at Matt Breuer. “Have the barman send me a Martini.” He installs another cracker between his jowls and crumbs fall down the front of his shirt. He dusts them onto the floor. Breuer turns to the barman, Igor, who is standing beside him with a towel over his arm. “Igor, this fine gentleman requires a Martini”. His sarcasm is liberal, and I cringe. But Breuer has always managed to elicit a curious devotion from the folks he most teases, and the fellow doesn’t even notice; he’s built a tower of baked brie on a toast point and it’s quivering en route to his mouth. I don’t know that balancing acts are this chap’s specialty.

Two tables run the length of the big tent. The tables end at the bar, which features draft beer, brewed in Murmansk and delivered weekly by helicopter. Behind the bar, a vast wine and liquor selection is arranged above a dedicated Vodka freezer. Vodka is very important here. I sit down on a barstool and rub my liver. About me is a hum of good will; guests clink drinks and compare notes on recent sporting travels. I’m feeling a little bush-league when Breuer sweeps in. “Igor, we need three beers… I’m taking a tour of camp.” Igor, apparently accustomed to such requests, smiles and complies, and Breuer hustles me out the door and into the open air, scooping up Carter on the way. We’re in Breuer’s wheelhouse now, and what lies ahead is anyone’s guess, but I anticipate a hangover at the end of it.

Breuer crams us into an ATV, and we tool through camp at a magnificent rate. Fortunately, he and Carter are side by side in the front seats, and their combined weight has got to exceed 500 pounds, so I’m confident we won’t roll the thing. Breuer takes a tight turn and the back wheels slide out, pushing gravel off into the birches. My beer slings out over me and the tundra, and Breuer shakes his head. “That will be reflected in your bill.” He’s mentioned this on other occasions. “Now hold on…” Breuer gives it some gas and whips us around and we stop at a long, low building. “Good. Let’s start our tour.” Breuer leads us from the gym to the Banya, a glorious sauna of wood milled on-site, then to the luxury shower house, then to the climate-controlled wine cellar. Ponoi River Company owner Ilya Sherbovich has built a 5-star hotel thousands of miles from anywhere. It’s kind of unfathomable. Breuer aims the ATV in the direction of the Big Tent. He misses by a wide margin, and winds us up beside the river.

The Ponoi is broad and coppery-dark, and gloomy enough to hide a cobbled bottom. Seams and oily slicks braid themselves downstream. The river has cleaved a path towards the White Sea that is ragged, and the riverbanks are, in most places, precipitous. Seemingly, a wall of water poured through this place not so long ago, chiseling out a channel and leaving behind a river that can’t hope to fill the crack. The tundra sits on a plateau above, and as we approach the river’s edge, I can’t help but think that we are hidden down here. We walk to the water and I touch it; it’s colder than I assumed. Carter points; a hundred feet out a salmon leaps, squirting from the river and tumbling back down. It’s the first Atlantic salmon I’ve seen in the flesh, and the sun hits it hard and bounces back at us like a beacon. The flash makes it look bigger than it likely is, and leaves a spot of white in front of my eyes.

“Let’s get some dinner.” Breuer is already swinging back into the ATV, with Carter just behind, and I look once upstream, towards the late-day sun.

10 AM on Sunday I’m finally on the river, but Spey casting is a bother. I step off the foredeck and hand my rod to guide Dan Podolski. Dan and I are far from camp, which is far from the nearest village, which is far from anywhere. We’re fishing the Ryabaga’s topmost beat, which lies an hour upstream of camp by jet boat. Each pair of anglers was allotted a guide and a beat at random the previous night. The morning fog lifts gradually, carrying my hangover with it, and my eyes are clear. In the past, I’ve fly-fished through a myopic lens, favoring the small streams of my native New England. I am used to delicate presentations made with delicate rods, and I’ve grown accustomed to delicate fish. New to Spey casting, and beset by an ego that loathes a line that refuses to fall in a tight loop, I hand the rod to Dan in order to watch one of the world’s finest casters.

Dan grew up with a Spey rod in his hands, and his movements exhibit a beautiful economy of motion. In a subculture of anglers fascinated by the arcane, he is a master of a particularly esoteric craft. With a flat, flicking motion, he paints a shallow C with his rod tip that opens downstream, and lays the leader up above him. He sweeps the rod tip back, charging the line behind him in a loop that leaves only the tiny fly on the surface of the river. Dan’s body cocks like a corkscrew over his shoulder, pausing as the line loads. All motion stops. The river rushes, and the clouds move with glacial sloth while Dan and his cast become a frozen moment. Then he uncorks it, powering forward with a flick of elbow and wrist that drops the rod tip nearly back to the water. In an instant, he is perched like a heron, smiling as the fly sweeps an arc across the current, nearly 150 feet from where he stands. I look downstream at the track of Dan’s fly, where it rides under the surface. Something surges behind it, and Dan moves quickly, stripping in the line and clucking his tongue. “Good fish there. You cast now,” and he points towards the receding swirl. I take the rod and do my best, trying consciously to think of other things and let the rod do the work. It feels good and unfurls towards the fishy place, but nothing moves. “Again,” says Dan, and I cast again, thinking way too much this time, and the line piles up. I strip in and try to cast again, but the strain of a botched attempt and a big fish have me unglued. I bungle the whole thing and slap my rod on the water. Then, as I’m thinking about chucking my rod in the water, an Atlantic salmon eats my fly. He must have been almost under the boat, and he took a fly that was just hanging there, attached to a defeatest bastard with entitlement issues. He likely knew that, for he took off like a shot, presumably thinking in his primitive brain “as soon as I start pulling, this sonofabitch is gonna decide he can’t land me, and I’ll take whatever’s left of him waaaaay upstream.”

Atlantic salmon are known for their power, but they can play things close to the vest. They can be coaxed through the current, making you second guess all of the rumors you’ve heard, and then they see the boat, or the net, or the guy in the river with the stick in his hands. That’s when they smoke you. They explode with an aerial escape plan that sends them spiraling hundreds of feet from the rod tip, twisting and head-shaking until physics put demands on the hook that it can’t hope to live up to. I’m watching the fish skipping away over the shimmer of water and I realize, with the release of line through my fingers, that none of this makes sense at all.

This fish is flying away yet staying attached somehow, and there is, communicated through the line and into my hands, a wildness that is beyond the physical, or perhaps elementally physical. I don’t understand this fish, the things he’s seen on his journeys, the reason he’s chosen to become acquainted with me. But we are now connected and waging a sort of ludicrous war, and I’m trying to convince him that I’m not a bad guy, and I just want to get that sharp thing out of his lip. We struggle back and forth and finally I swing him near and lift his head. He materializes, blazing under the sheen of water, and Dan stabs with his net and there we are, in the presence of, but somehow not in possession of, a slab of August silver.

2 PM on Tuesday The bank below camp is broad and flat, but the cobbles are hard to walk over. There are big boulders, and tributaries that trickle off the tundra, joining the main river. Lunch is laid out by the water, and a birch fire keeps the no-see-ums down. The moist wood will lend some smoke to the salmon fillets we’ve kept for lunch. A shore lunch on Ponoi features soup and tea, bread, cookies and always cucumbers. And when a salmon takes the hook fatally, it features fish. The guides are unapologetic about this, and they thump the fish soundly and serve them almost at once. Some are grilled over live coals, and sprinkled with salt and pepper. Others are slivered into sashimi that is the very temperature of the river. From my vantage up here on the bank, I watch Max Mamaev hunched over his cutting board. The fillets that fold off of his knife are sunset pink, and command the scene. Carter and Heidi sit on a boulder drinking Grolsch beer, and laughing at Breuer, who is dancing around in his waders, gesturing wildly. I can’t hear his story over the rush of water, but his pantomime is spectacular, and I smile too. Beyond my friends flows the river, where salmon show in their telltale leaps. Beyond them is the sheer far bank, collapsing in places to the water. Above the ledge a sky sweeps over the lip of tundra all the way to the North Pole. At this moment, I realize how far I am from anywhere I know, and yet how familiar it all is. I’m a fisherman, seeking the same connection I seek at home, and that is universal. I sit down at the edge of a tributary pool and watch the ravens spinning off the far cliff. I look down at Breuer, and Carter, and Heidi, who’ve fished across the continents for hundreds of species, becoming famous names among those who cast flies. I look at Max, peeling back the flesh of a salmon that, an hour before, was travelling a timeless homeward path, and who chose to become part of our day, and part of our collective memory. I look at Dan Podolski, poking the fire with hands full of artistry. We are far from anything and right next to all of the mystery in the world, and I’m suddenly full of gratitude for my presence here. I might even understand why we’ve come. The guests in camp, the guides, Ilya… they have chosen to lean against something that eludes them. These men and women, be they phenomenally wealthy or phenomenally skilled, or, in my case, phenomenally lucky, have come here to present themselves at the hands of something that transcends success or failure. Salmon will bite or not, regardless of skill, or entitlement, or money, as rivers will rise and fall. They can’t be cajoled. We seek their communion with outrageous precision, all the while knowing that it is for naught; they’ll be the ones to decide. Here we seek the magic and mystery that is essential, and the rich colors that lie beneath the skin. The salmon know this, and remind us, and return to do it again.

First published Gray's Sporting Journal