Kick ‘Em Up

There’s a fellow down the street from here with a ringneck decal on the rear window of his truck, and another that spells out, in those aggressive die-cut letters “Kick ‘em up, knock ‘em down”. Call me crazy, but I’ve pegged this guy as a pheasant hunter. Now I don’t know him at all, though around here, bird hunters comprise a small fraternity, and we tend to haunt the same pockets and hedgerows. But despite our remote kinship, I always have a laugh at this poor bastard’s expense; after all, in the vicinity of our Massachusetts home, the only pheasants he’s hunting are the grain-fed travesties that the state buys like chickens, and salts out through the hayfields in the October twilight.

It pains me to shoot pen-raised birds. It pains me, but I do it anyway, because there are times when I find that it’s the only game in town. Hunting on a shoestring budget, around a work-cum-wife-cum-daughter schedule that grows more intricate with each passing year, I lean on the mockery of my local bird hunting like my alcoholic grandmother leans on the bottle of cooking sherry. Now that’s not to say we don’t have wild birds here, in the woodlands once tramped by the likes of William H. Foster, Tap Tapply, and Burt Spiller. But the progress of man has all but confined the partridge to slips of bittersweet tucked behind the ‘POSTED’ signs, and the woodcock that my bell-wearing Brittany pins to the alder bottoms are all but too fleeting to shoot. So I “kick ‘em up, knock ‘em down” and fill my January oven with what my daughters tend to think of as ‘chew-it-soft chicken’, what for the smattering of number 6 shot. I’m not proud. I’m just freakishly bent towards full disclosure.

But I suppose in the evolution of any wayward bird hunter, there lies a moment of absolution, a realization of the soul of this thing we call sport. And when that cathartic moment comes, it isn’t grain-fed, or pen-raised, or planted in the brush by a sleepy-eyed state employee. It’s cut from the wind and the sky and the pure driven joy of a bird framed against brush awash in sunlight. Or that’s how it hit me, anyway. And it hit me hard in the shoulder, with the recoil of a box of 3” 20 gauge shells, and a game bag heavy enough to give me pause. And it was willow ptarmigan that did it.

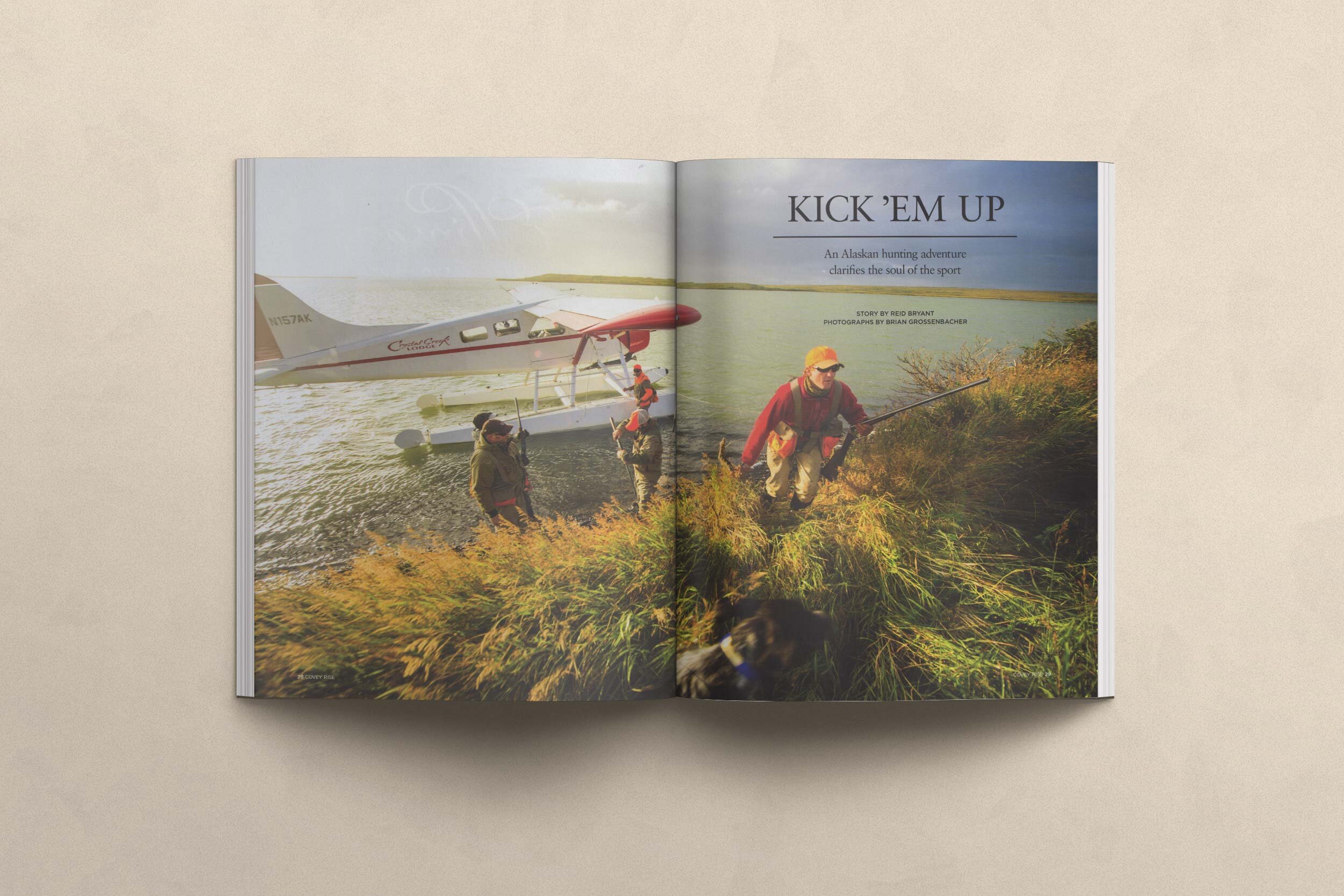

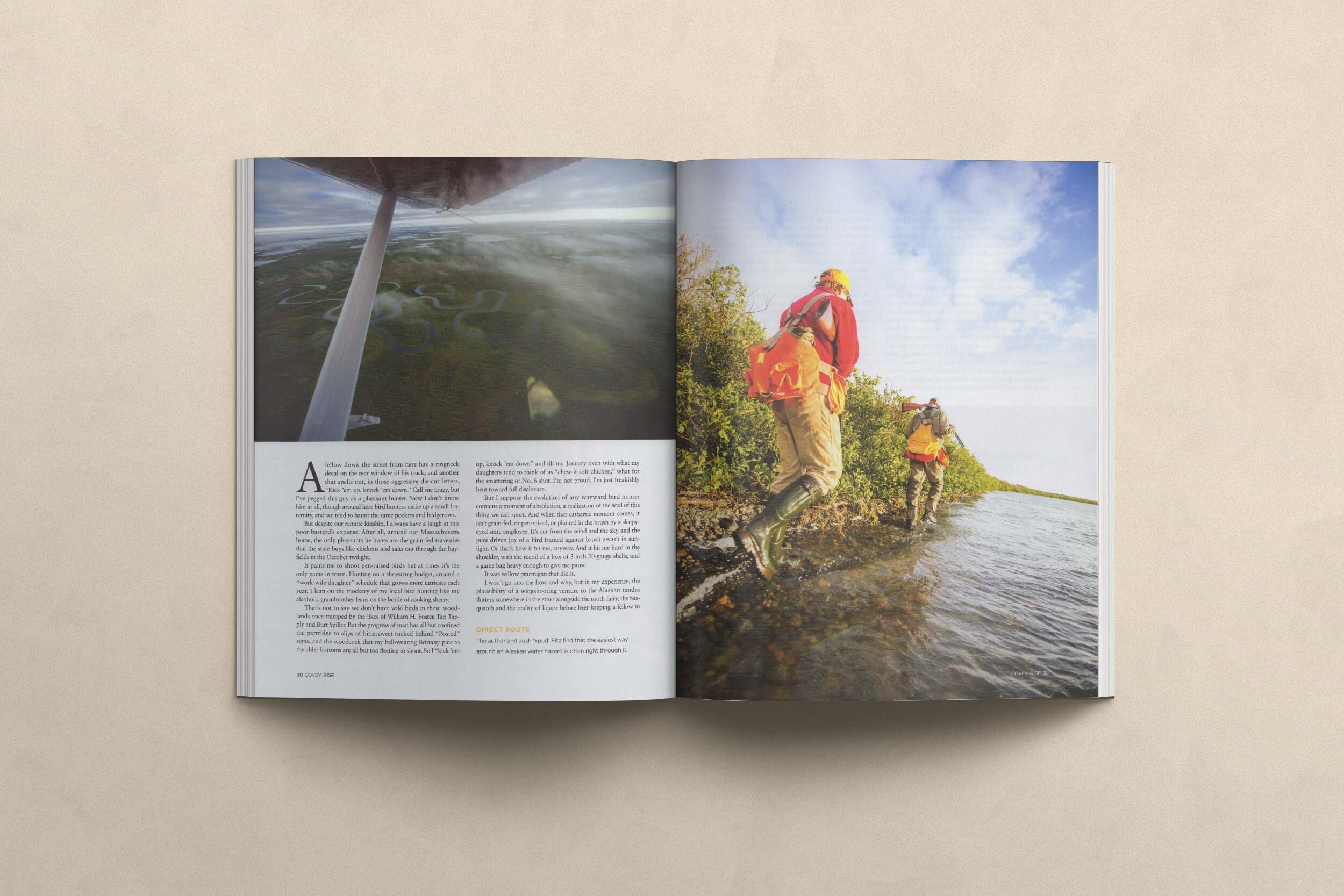

I won’t go into the details of the how and why, but in my experience, the plausibility of a wing-shooting venture to the Alaskan tundra flutters somewhere in the ether alongside the tooth fairy, and sasquatch, and the reality of liquor before beer keeping a fellow in the clear. But at times, magic manifests in the most gracious of places, and when a reknowned artist friend offered a week’s worth of hunting, well, I’m not one to look a gift horse in the mouth. So it transpired that I found myself at Crystal Creek Lodge in King Salmon AK, loading a quivering Wirehair into a float plane and hoping that my long-held fear of flying wasn’t any too apparent. The guns were packed, alongside the shells and the lunch and the bear spray, and nestled in too was an excitement real enough to make my hands shake.

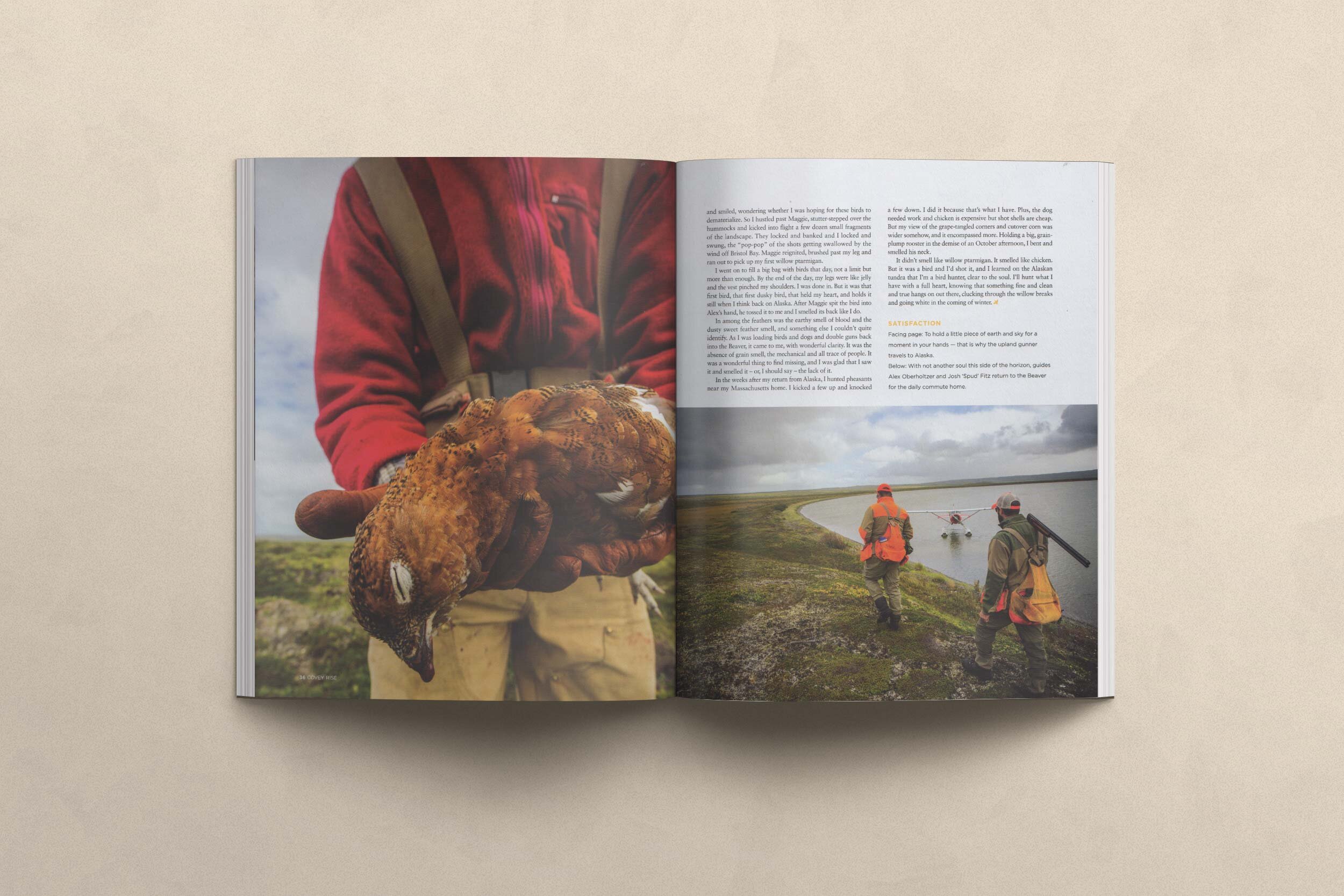

We lifted off the Naknek River into a gunmetal sky, and if surreal weren’t enough the word for it, a hint of a rainbow showed in the east. Brian, my artist buddy, was in the seat ahead of me, alongside Josh Fitz, aka Spud, aka one of Alaska’s finest bird hunting guides; Maggie the Wirehair sat beside him. Alex Oberholtzer was at the controls of the Dehavilland Beaver, his prizefighter frame crammed impossibly behind the console, and I was in back with the gear. It was ok with me. Being behind those guys and all, they couldn’t see me shaking, either with fear (I’m a loser), or with excitement (I’m still a loser). As we rose, the landscape below us and ahead took shape, and became a patchwork quilt of spruce forest, and tundra, and riverine streaks of silver. It was vast, too big for me to make sense of, and surely too big to exact a likely piece of cover out of. But Alex O. at the helm seemed sure enough of his course, and no one else was asking questions, so I pressed my nose to the window and soaked it all in. Maggie, sensing the welling inside me, brought it all back into focus with a sloppy-wet kiss on the cheek. A thousand feet up was all the same to her, and we were going hunting, over pointing dogs, for the wildest of wild birds. Maggie smiled and slopped up my cheek again, and I smiled too, and gave myself over to the great unknown of adventure.

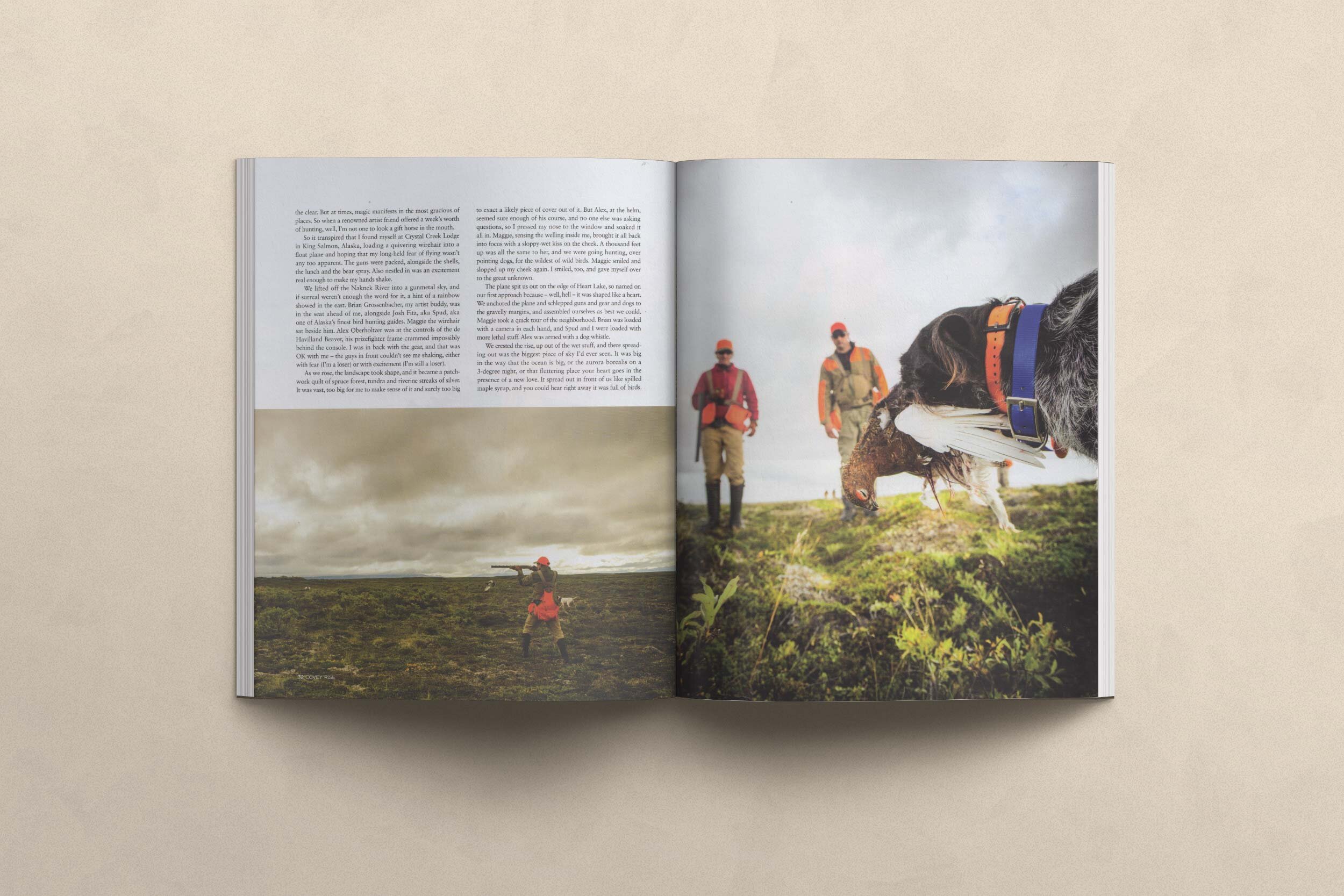

The plane spit us out on the edge of Heart Lake, named Heart Lake on our first approach because, well hell, it was shaped like a heart. We anchored the plane and schlepped guns and gear and dogs to the gravelly margins, and assembled ourselves as best we could. Maggie took a quick tour of the neighborhood. Brian was loaded with a camera in each hand, and Spud and I were loaded with more lethal stuff, and Alex was armed with a dog whistle. We crested the rise, up out of the wet stuff, and there spreading out was the biggest piece of sky I’d ever seen. It was big in the way that the ocean is big, or the Aurora Borealis on a 3-degree night, or that fluttering place your heart goes in the presence of new love. And it spread out in front of us like spilled maple syrup, and you could hear right away it was full of birds. There was a clucking wave of them moving like an apparition over the rise a hundred yards out, and they sure as hell weren’t waiting ‘round for the likes of us. So we snicked the guns closed and AO released Maggie, and the birds sifted fast into the willows.

I like to think of a dog on point as a moment suspended in time. In part it’s the stark departure of all of that motion, a coilspring ball of wide-eyed, wirehaired, slobber-stained muscle slamming to a standstill in an instant. If you are one of those forest-for-the-trees types, you wait for a second behind a pointing dog and consider the spectacle. The dog is held on the cusp of something through centuries of line-bred restraint. A bird hunter is held in the same sort of reverie, but for a few different reasons. In my case, when Maggie locked up and dropped her chest to the ground, it was a resounding realization of good fortune that stopped me: somewhere out ahead, clucking and shuffling were more wild birds than I’d seen in a lifetime, birds that had never seen men before, or pointing dogs, or asphalt gravel. I knew all at once that my first step into that covey would slice to the heart of bird hunting at it’s cleanest, and best. It was all there just ahead, and I realized it fully, and joyfully. I was thinking these things when Spud walked up and thumped me on the back, and smiled, and wondered whether I was hoping for these birds to de-materialize. So I hustled past Maggie, and stutter-stepped over the hummocks, and kicked into flight a few dozen small fragments of the landscape. They locked and banked and I locked and swung, and the pop-pop of the shots got swallowed by the wind off of Bristol Bay. Maggie re-ignited, brushed past my leg, and ran out to pick up my first willow ptarmigan.

I went on to fill a big bag with birds that day, not a limit, but more than enough. By the end of the day, my legs were like jelly, and the vest pinched my shoulders, and I was done in. But it was that first bird, that first dusky bird that held my heart, and holds it still when I think back on Alaska. Maggie spit the bird into AO’s hand, and he tossed it to me, and I smelled its back like I do. In among the feathers was the earthy smell of blood and the dusty sweet feather smell, and something else I couldn’t quite identify. Loading birds and dogs and double guns back into the Beaver, it came to me though, with wonderful clarity. It was the absence of grain smell, and the mechanical, and all trace of people. It was a wonderful thing to find missing, and I was glad that I saw it, and smelled it, or the lack of it I should say.

In the weeks that followed my return from Alaska, I hunted pheasants near my Massachusetts home, and kicked a few up, and knocked a few down. I did it because that’s what I have, and the dog needed work, and chicken’s expensive but shotshells are cheap. But my view of the grape-tangled corners and cut-over corn was wider somehow, and encompassed more. Holding a big, grain-plump rooster in the demise of an October afternoon, I bent and smelled his neck. It didn’t smell like willow ptarmigan. It smelled like chicken. But it was a bird, and I’d shot it, and I learned hard and fast on the Alaskan tundra that I’m a bird hunter, clear to the soul. I’ll hunt what I have with a full heart, knowing that something fine and clean and true hangs on out there, clucking through the willow breaks and going white in the coming of winter.

First published in Covey Rise