In the Rough Hills North of Trevelin: Part II

Nearly a hundred years after Butch and Sundance slipped away, nearly twenty years since he and Travis had first similarly wandered south, Rance Rathie pulled through the PRG Lodge head gate and aimed the truck towards the village of Trevelin. A coffee cup was wedged between his knees, and he fiddled with the radio dial until a crackling traditional milonga turned up, scoring the whine of the Toyota diesel, and the scuffle of the pointers in the dog box. Rance cleared his throat and turned to me, slowing to a stop on the bridge shoulder. He rolled down the window to a gray May morning and peered out. Twenty feet below, a small stream eased along the base of the hill and wandered into the village. “If I’d have thought of it sooner,” he said, picking up his coffee cup and gesturing with it, “we could have given you a shot at an Argentine McNab.” He cleared his throat again. “After the day you had yesterday, the trout would have been easy…”

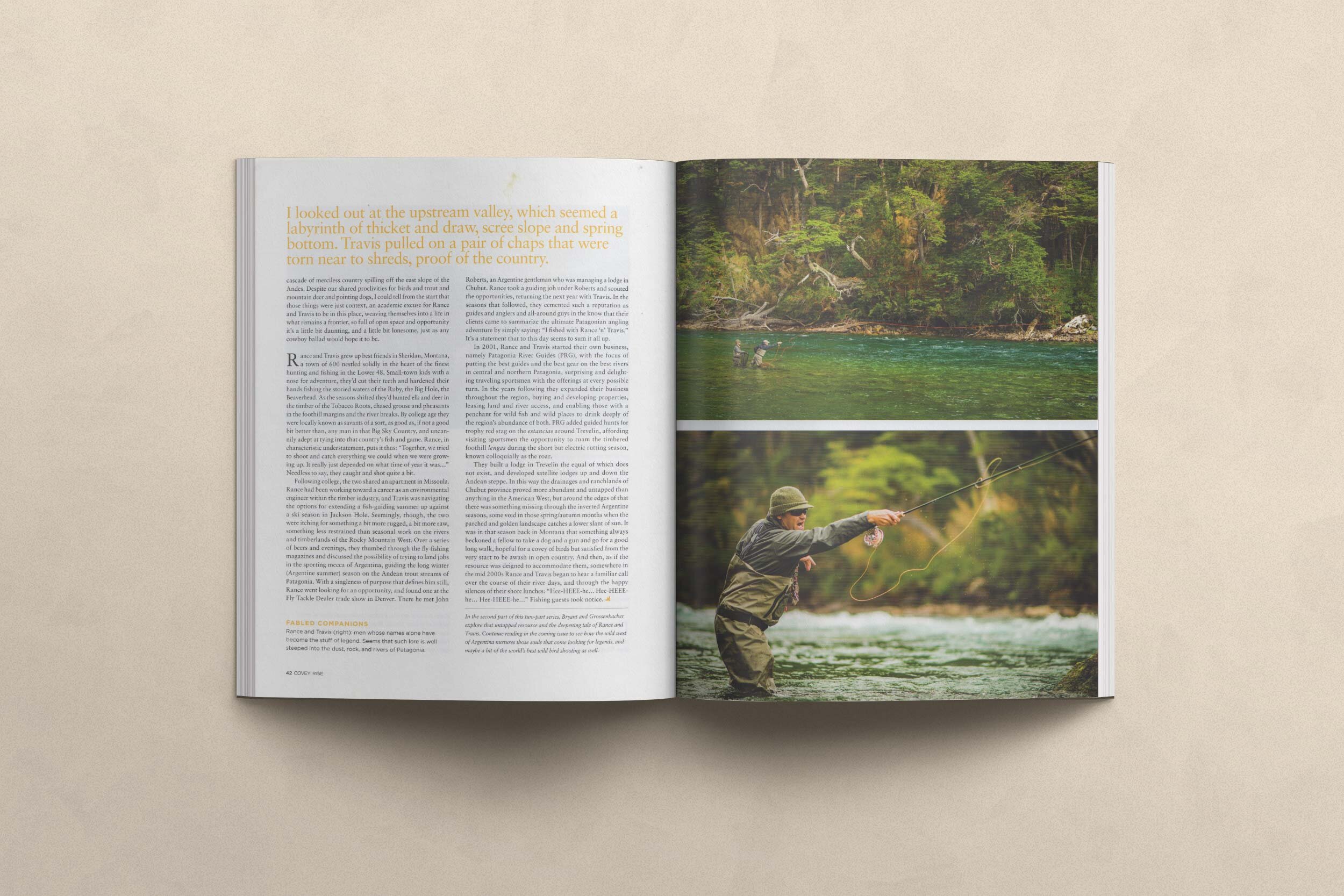

He put the truck in gear and slipped off the bridge and onto the broken macadam of the provincial road, tapping his fingers in rhythm to the radio’s gaucho guitar. Rance’s reference to my big day was perhaps a generous one, but appreciated nonetheless. The day prior, which had dawned rain-soaked and angry, had turned up a hard-won red stag for me well before breakfast, and a bagful of valley quail in the hours after lunch. We’d been hunting the region’s stags with intention for a few days running, Rance with a bow, me with a rifle, circling through the knobby headlands by day and regrouping at dark to share our stories. With three days spent and no chance at a stag, we’d planned to trade bows and bullets for shotguns, and chip away at the massive coveys of quail that were scattered through the brushy draws. But Rance, sensing my defeat, had encouraged me out for one last morning. In a squalling rain a stag had emerged through the mist, and it fell with one shot, tumbling down a sand slope to the valley floor. With gratitude offered and some celebration, the sun broke the morning and the sky opened up. At that we’d hunted quail till near dark, achieving a surfeit of sport and an awareness of abundance offered up by a clean and lovely land. A trout would have punctuated that day in a nominal sense only, as at some point one must appreciate the unrestrained sufficiency of enough. To my eye, what Rance had provided on that day prior was more than sufficient, and it cleared our eyes of horned distractions, that we might focus on dogs and birds.

We stopped in Trevelin for cigarettes. Rance smoked one beside the truck, and the dog handlers Adolfo and David eased up and idled, and rolled down their window. They too had dog boxes in the truck bed. Rance leaned in and spoke to them in his unhurried Spanish, and they seemed to make a plan. Adolfo and David pulled away and Rance pinched the ember off his cigarette and pocketed the butt. He started the truck and followed their ascent out of town, and began in parallel to thread his way back towards the story that I’d asked him over the phone some months before, when the plan for a visit first hatched. “When Travis and I first got here, we didn’t see any quail,” said Rance, gearing down for the incline out of Trevelin. “But the after the third year or so, we started to see about a covey a week, and in the last ten years the numbers have just exploded.”

Rance went on to describe how, as in the case of many homegrown species introductions, Valley Quail arrived in the region back around 1965. It was, by most accounts, in that year that the Larivière family, who owned the Estancia Arroyo Verde in Traful, released six pair of pet quail on the estancia grounds, hoping for a nominal, novelty population to take hold. Apparently, that six pair found a welcoming climate and suitable habitat, and they proliferated. Over the years, their numbers expanded north and south of Traful, and in the recent period of warm dry weather, the covey sizes and densities have flourished. “They can handle all but the most crushing weather Patagonia has to offer, and they don’t really have many predators. Besides that, the local landowners and even the gauchos don’t hunt them at all, as generally there isn’t much of a rich bird hunting culture among Argentines. Those that do hunt birds head to La Pampa, Santa Fe, and Buenos Aires provinces for perdiz, and these quail just get left alone. We don’t mind that at all…” Rance smiled, and as if on cue a trio of top-knotted birds skittered out into the road ahead, turned tail, and flushed. They picked up a dozen more on their departure, set their wings, and coasted. As we passed, I looked back and watched them bank into a clump of Calafate brush, and disappear.

*

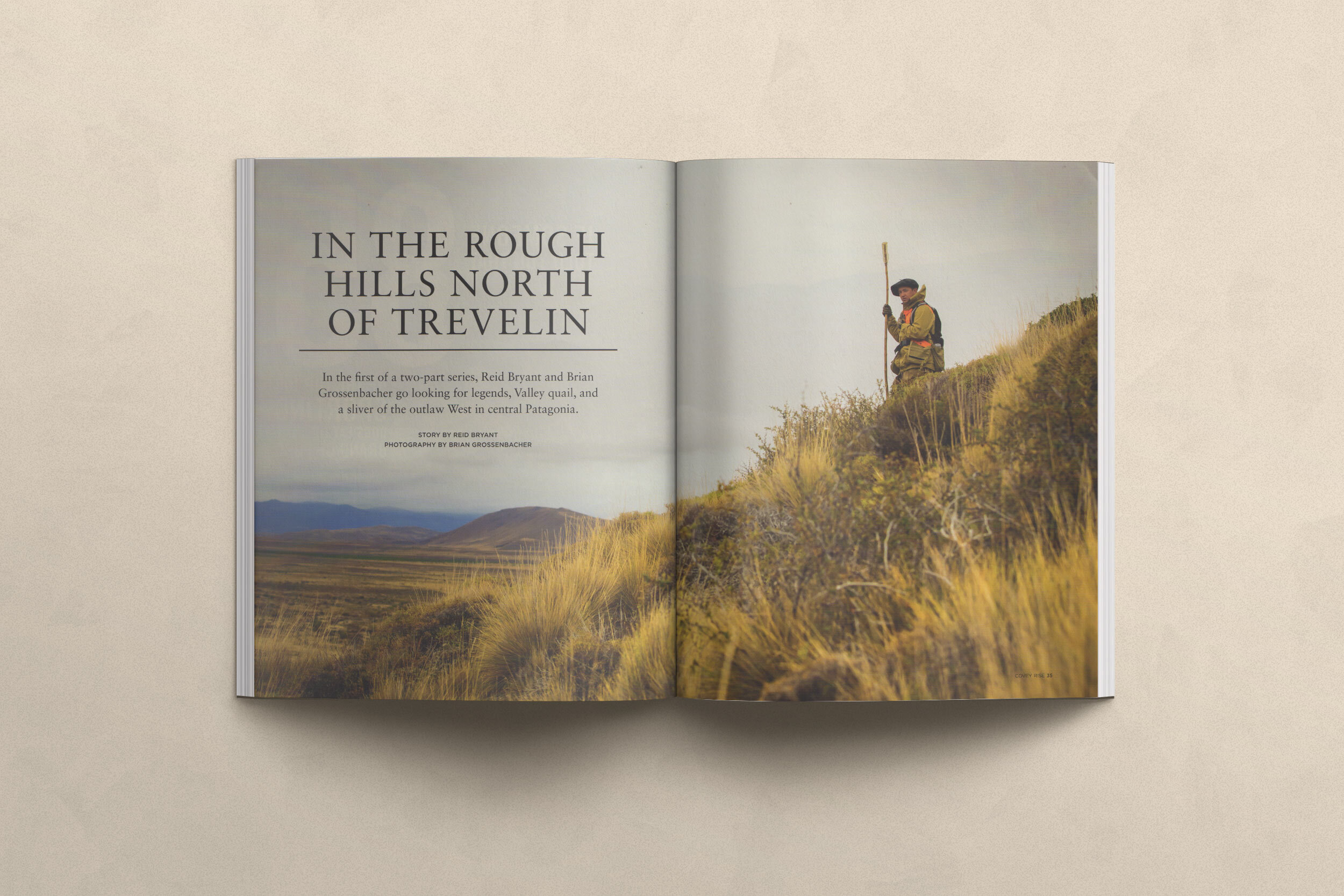

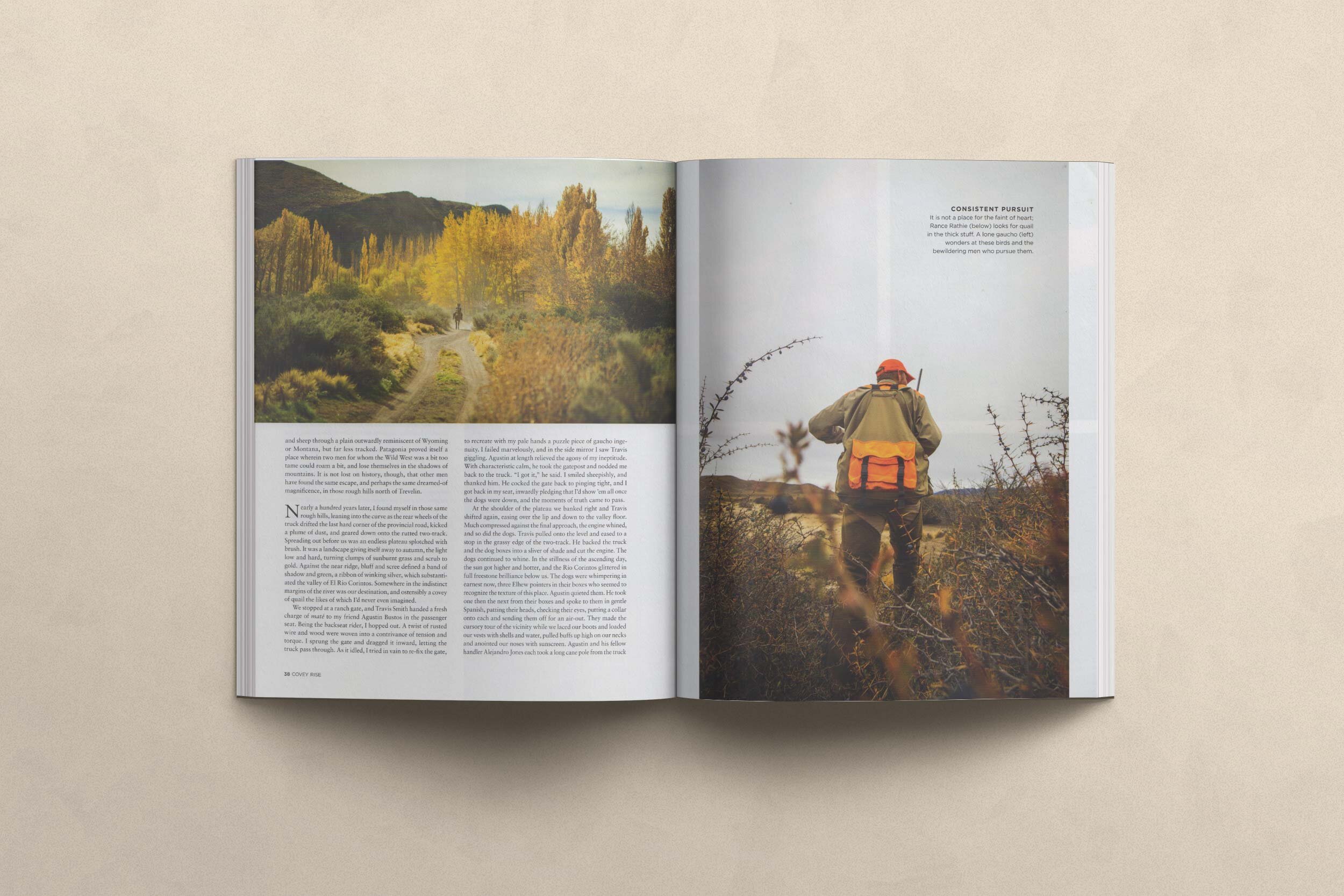

Over the ensuing days I hunted with Rance and Travis, following pointers handled deftly and quietly by Agustin, Alejandro, Adolfo, and David, through the bowls and draws and valley flats around the Sunica Ranch and El Rio Corrintos. It was hunting both familiar and unlike anything I’d seen before. We’d drive through ranchlands on washboard roads, across miles of uninterrupted space. The higher mountains, often draped in clouds, punctured the low ceiling periodically in swatches of blue sky and sunlight. On the stretched strands of wire fence hung the odd raw sheepskin, sundried and stiff, waiting for collection by the gaucho who’d left it there days or weeks before. We’d park in the brushy bottoms and drop a brace of dogs, and the handlers would dress in their waxed cotton armor, as we loaded our vests with shells. Adolfo or Agustin, cupping and pinching a small, home-grown quail whistle to their lips, would locate a covey, and then cast the dogs, and off we’d go in pursuit. Hunters would flank and walk just ahead of each guide or handler, who in turn would watch the dogs and look for hard points and hard redirects, poking the Manca Caballos, Calafate, Una de Gato, and Coiron grass with their rivercane lances. Topping each of these poles was an empty plastic water bottle, a device of which I was first skeptical. “Adolfo came up with that one,” Rance told me, smiling at Adolfo. “It’s something about the crackle. This brush is impenetrable; even the dogs can’t get into it, and the quail know that. When we started, we chucked rocks into the bushes to get them to flush, but the bottles and poles drive them crazy.” As if to demonstrate the efficacy of his invention, the hulking Adolfo speared his bottle deep into a thorn bush and wiggled it about.

We’d walk the bowls and bottoms this way, springing rabbits from their hides, sometimes seeing a quail or two scurry and flush just ahead, cup, and re-settle. On the leading edge of the main covey the dogs would lock and creep, and the handlers would encourage us up forcibly, and we’d hustle to do their bidding. Close on our heels they’d beat and stab the brush, and push the dogs up, and invariably a bird or two would bounce out, often either behind or between us, or so far to our flanks that a shot was unrealistic. But then at some point the covey would rise in earnest, and a mounting swell of birds would pulse out, the first wave pulling the rest from the brush as they passed over. Some of those coveys numbered in the hundreds, with stragglers and singles popping like corn, and presenting those low and odd-angle and wholly unpredictable shots that make valley quail quite wonderful. We’d shoot and miss and be urged on by the handlers, and we’d reload and shoot again, sometimes hitting a quail hard and watching him carry far farther than we ever thought possible for a diminutive bird, pitching down to tumble dead amidst the scrub and scree. I recall watching Travis on the side hill below me take a poke at a straightaway cock bird that bloomed with a puff of cut feathers, and continued on as if pushed. He dropped the bird with a second barrel, but Adolfo only picked it up a hundred yards farther on, what for its tenacity of life. Such is the strength of wild birds everywhere, but somehow the Patagonia birds were even tougher, tough as nails, tough as the raw and rugged land itself, and the men who live there.

*

On the last day in the afternoon, a gray sky that had threatened all day made it cooler, almost chilly. Rance and I had walked two properties and given ourselves a festival of shooting, with birds enough to botch a good few, and learn from our mistakes. The dogs worked valiantly and held staunch, and Adolfo and David, having beat the brush in a grueling frenzy for hours and miles, seemed quietly none the worse for wear. I for one was spent. We were near a lodge limit of fifteen apiece, near the end of the fencerow and the truck, near the end of a trip wherein the size of land and sky and wilderness had proven far beyond the limits of my expectations, or my capacities for conceptualization. We’d seen, I dare say, hundreds and hundreds of birds that day.

Conversation had wound its way down due to the late hour and the miles, but with Rance and Travis both I’d found an easy welcome, and the thing you find with friends wherein you don’t need to fill the softer moments with words or actions defined. I was swinging along and thinking about cold Quilmes beer and silence and the biggest gifts and the simplest ones when the bottle crackle thwack sent a last few birds out to my 11:00, banking for the foothills south. Rance never even closed his gun, just watched them go, and smiled. “There are lots of quail here,” he said, again indulging me in his characteristic understatement, which was pregnant with humor and thought and, to my mind, some philosophic brilliance. Yes, indeed, there are lots of quail in the valleys just north of Trevelin.

*

On the way out we stopped for one last gate, and I didn’t even try, but let David deal with it. We passed through and idled on the far side while David re-wound and wove and cantilevered wood and wire until it was pinging tight.

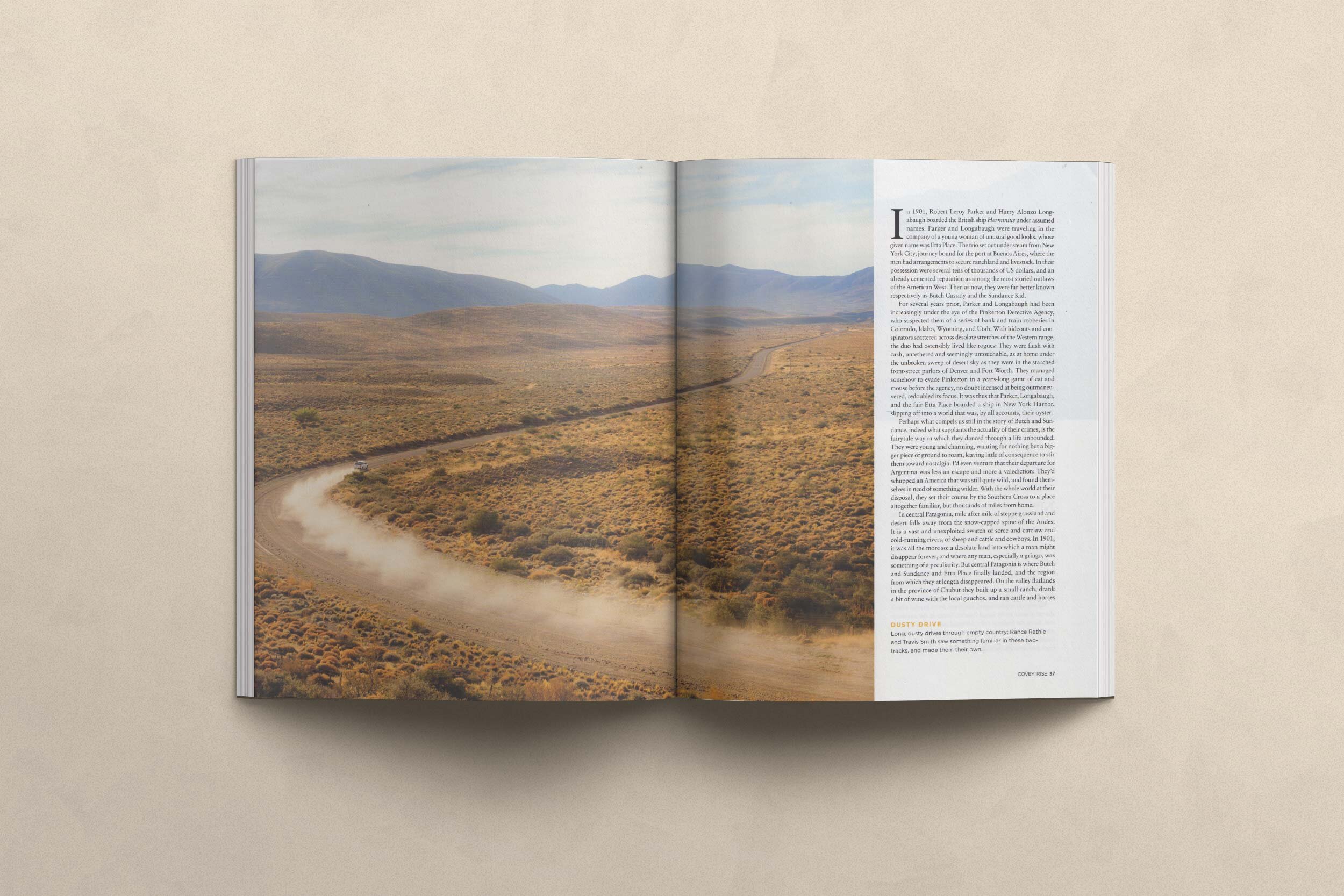

Talk had turned to Butch and Sundance. “Just over that ridge,” said Rance, pointing with fingers that held a smoldering cigarette. “That’s where Butch and Sundance had their ranch. Up the Cholila Valley. Probably less than 20 miles as the crow flies.” We’d been discussing the duo at points through my stay, weighing the local parables against the more starched and buttoned works of gringo history, parsing the hotly disputed theories of Parker and Langabaugh’s demise, or disappearance, or both.

“So what do you think happened?” I asked, trying to pin Rance down, perhaps trying to tease out something more definitive than his implied disdain for Pinkerton, and legend-turned-history, and the vindictive horse rustlers Wilson and Evans who’d killed a Welshman at Arroyo Pescado, thereby drawing the heat of the law into the sleepy Cholila Valley.

Rance took a long draw on his cigarette. “I don’t know. I guess anything could have happened.” He pinched off the ember and pocketed the butt, and looked off at the Andes as David climbed back in his truck and slammed the door.

“I guess what I think is that this is a big piece of country, and a hundred years ago a couple of men could disappear into it pretty easily if they wanted too.” He started the car, and pulled us out on the two-track, and cleared his throat again. He smiled. The day was starting to settle, and the clouds sifted lower over the foothills, softening the sweep of the scrub-strewn valley. Far off, a gaucho on horseback was an indistinct smudge of movement against the track.

“You know… I guess a couple of men still could.”

First published in Covey Rise