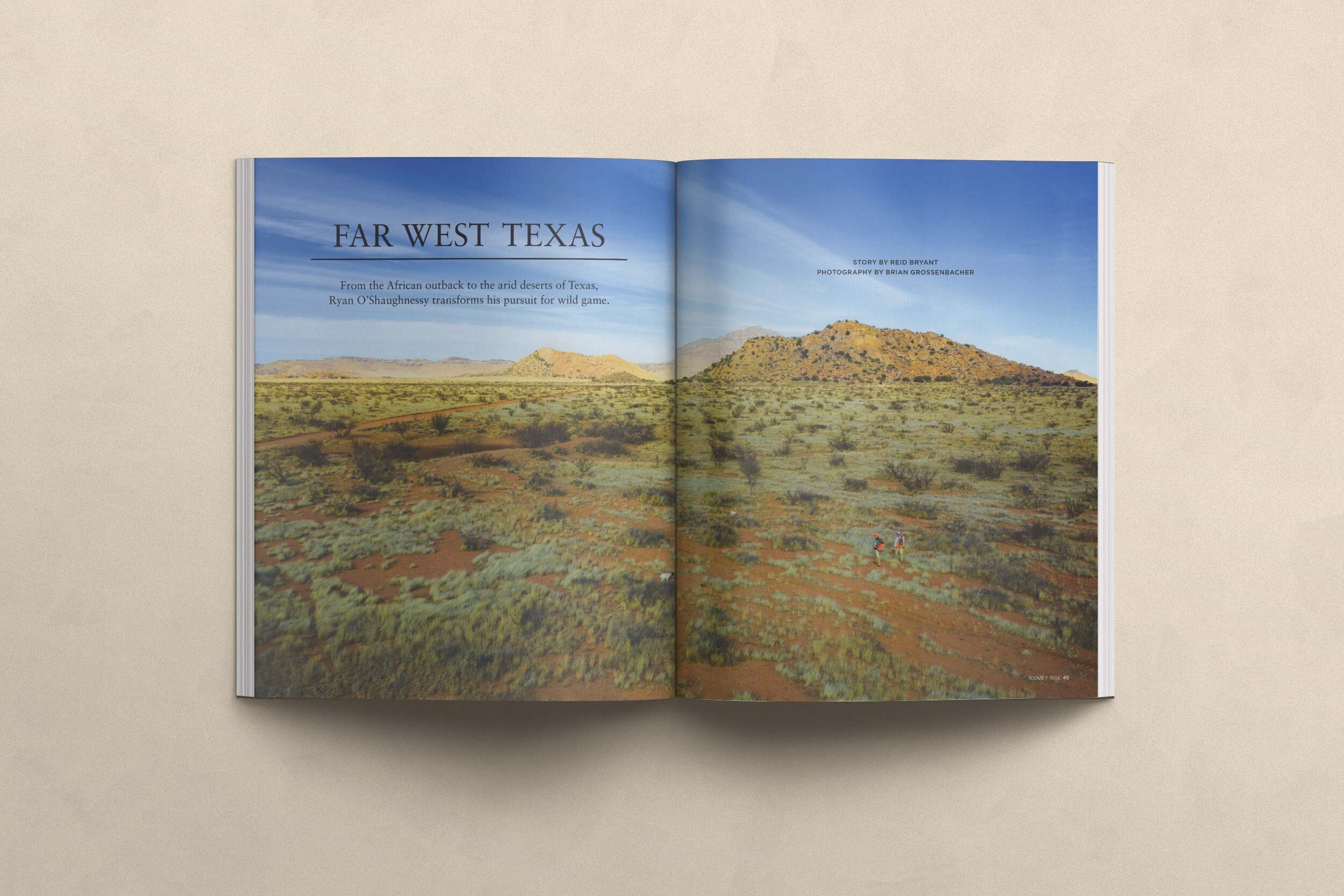

Far West Texas

“Son, not everbody thinks that life on a cattle ranch in west Texas is the second best thing to dyin’ and goin’ to heaven.”

The road was empty except for a yearling heifer that seemed uncertain what to do with her newfound freedom. We crossed the blacktop in the Willy’s and bumped down the shoulder a few hundred yards to where a swing gate broke the strung wire fence. Ryan O’Shaughnessy made a move to get out of the driver’s seat, but I got out first. He reluctantly sat back and put the jeep in idle.

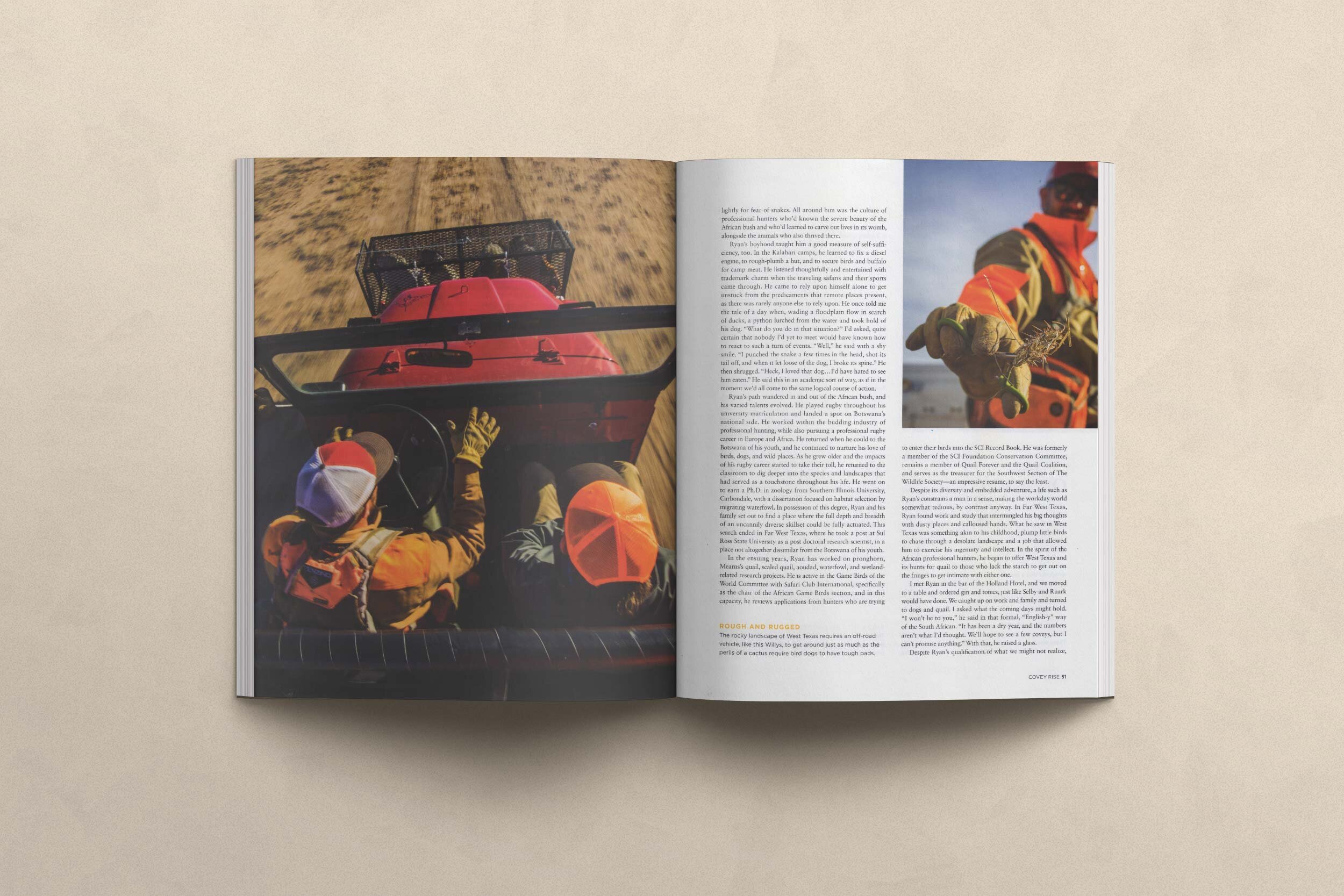

The gate was daisy-chained with a string of padlocks that hung heavy against the post. It was clear that something of value lay in the tens of thousands of acres beyond. The lock that had been assigned to Ryan was situated well down the chain; he called out the combination to me over the sound of the engine and I thumbed the numbers into register. The lock popped open and I pushed the gate in and held it wide, allowing Ryan and the Willy’s to pass on through. Inside the box on the front of the jeep the dogs had begun to scuffle and whine, noting the change in our progress that promised good things. I swung the gate closed and locked it again and we moved off down the ranch road into a sweep of spare grassland and yucca so big and empty and raw it made my chest feel hollow.

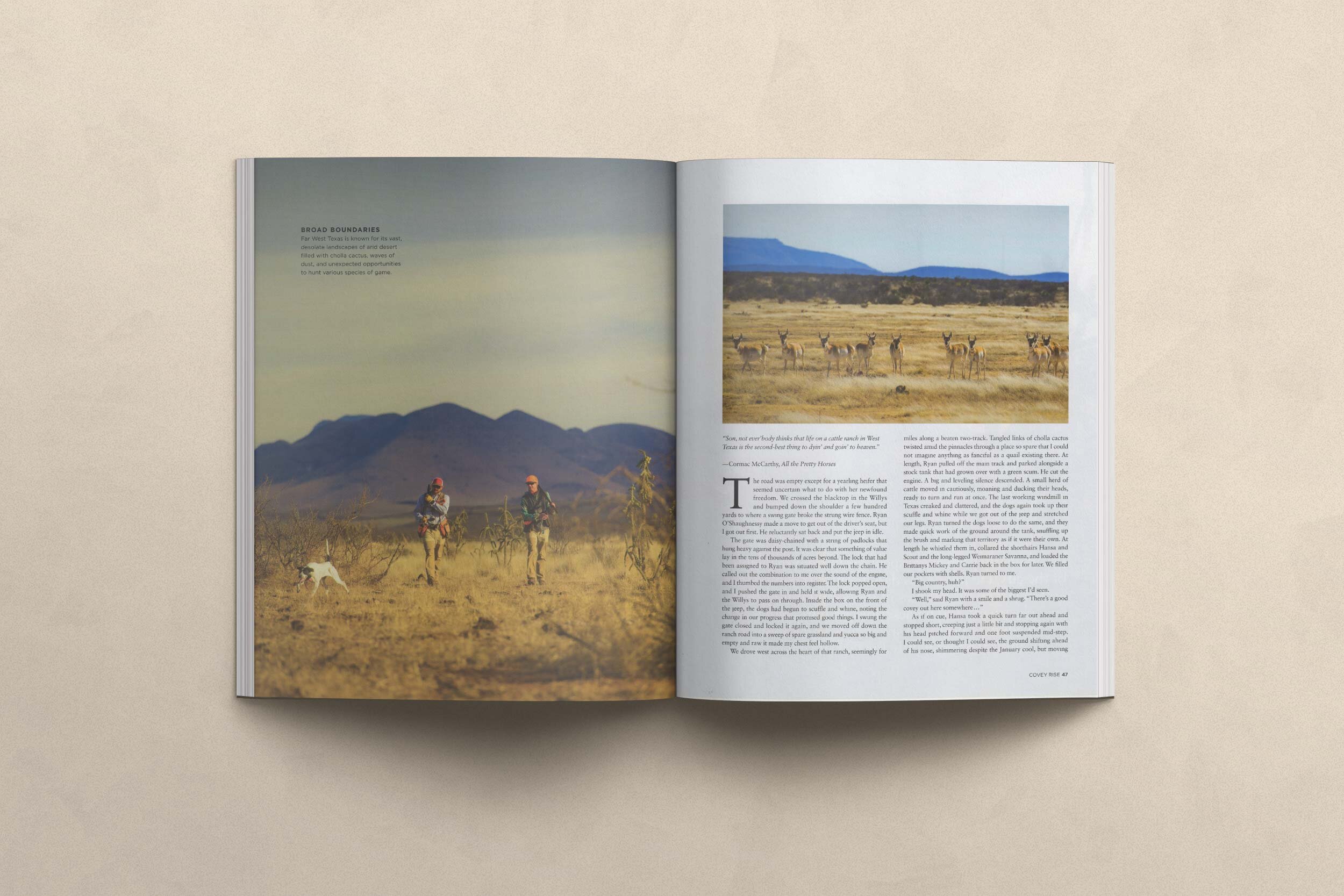

We drove west across the heart of that ranch seemingly for miles along a beaten two-track. Tangled links of cholla cactus twisted amid the pinnacles through a place so spare I could not imagine anything as fanciful as a quail existing there. At length Ryan pulled off the main track and parked alongside a stock tank that had grown over with a green scum. He cut the engine. A big and leveling silence descended. A small herd of cattle moved in cautiously, moaning and ducking their heads, at once ready to turn and run. The last working windmill in Texas creaked and clattered, and the dogs again took up their scuffle and whine while we got out of the jeep and stretched our legs. Ryan turned the dogs loose to do the same, and they made quick work of the ground around the tank, snuffling up the brush and marking that territory as if it were their own. At length he whistled them in, collared the shorthairs Hansa and Scout and the long-legged Weimeraner Savanna, and loaded the Brittanys Mickey and Carrie back in the box for later. We filled our pockets with shells. Ryan turned to me.

“Big country, ya?”

I shook my head. It was some of the biggest I’d seen.

“Well,” said Ryan with a smile and a shrug, “there’s a good covey out here somewhere...”

As if on cue, far out ahead Hansa took a quick turn and stopped short, creeping just a little bit, and stopping again, head pitched forward and one foot suspended mid-step. I could see, or thought I could see, the ground shifting ahead of his nose, shimmering despite the January cool, but moving nonetheless. Ryan and I closed our guns and scurried to catch up, taking a rough line in the direction of scaled quail and the southerly break of the Mexican border.

*

I’d come to west Texas the long way ‘round, allowing the region to unfurl and the promise of scaled quail to steep for a bit. It had taken me a full day to make the drive from Austin up out of the oak benches and into the Trans-Pecos, where the land got uncluttered. It was easy to eat up that country at 80 or 90, swallowing big chunks of highway. Brush country gave way to scrub grassland, and the Chihuahuan Desert gaped open, a plain of dust and broken rock that sifted off into a jagged horizon. This was a place known as far West Texas.

Far West… a landscape disconnected except by a piece of highway and the stretched ligaments of barbed wire. I slowed down to make the last turn onto highway 90 towards Alpine. The sun was slipping away, leaving just a glow. There was more than silence to this place, something a little bit cool and desolate. I was glad when night fell, and the lights of town flared, growing brighter as the last few miles rolled away. I turned off the highway and onto West Holland street and I parked outside the hotel. The bar was full of ranchers and oil-field gamblers, and I could see Ryan O’Shaughnessy leaning over his beer. He was smiling at the fellow beside him, who was pantomiming the swing of a shotgun barrel through the path of a bird remembered.

I first met Ryan a few years back, not too long after he moved to Alpine, Texas with his young family. He’d arrived in that region from the Midwest to take an Associate Professorship at the University, teaching Wildlife Management and conducting quail research while building West Texas Quail Outfitters in the hours between. On the surface alone Ryan was a man ostensibly given to learn all he could about a race of quirky and cotton-topped birds that would far rather run than fly, and to offer those birds to both students and hunting clients. But as I came to know him more, I uncovered the tale of a renaissance man, one whose unlikely presence in far West Texas demanded a bit of untangling.

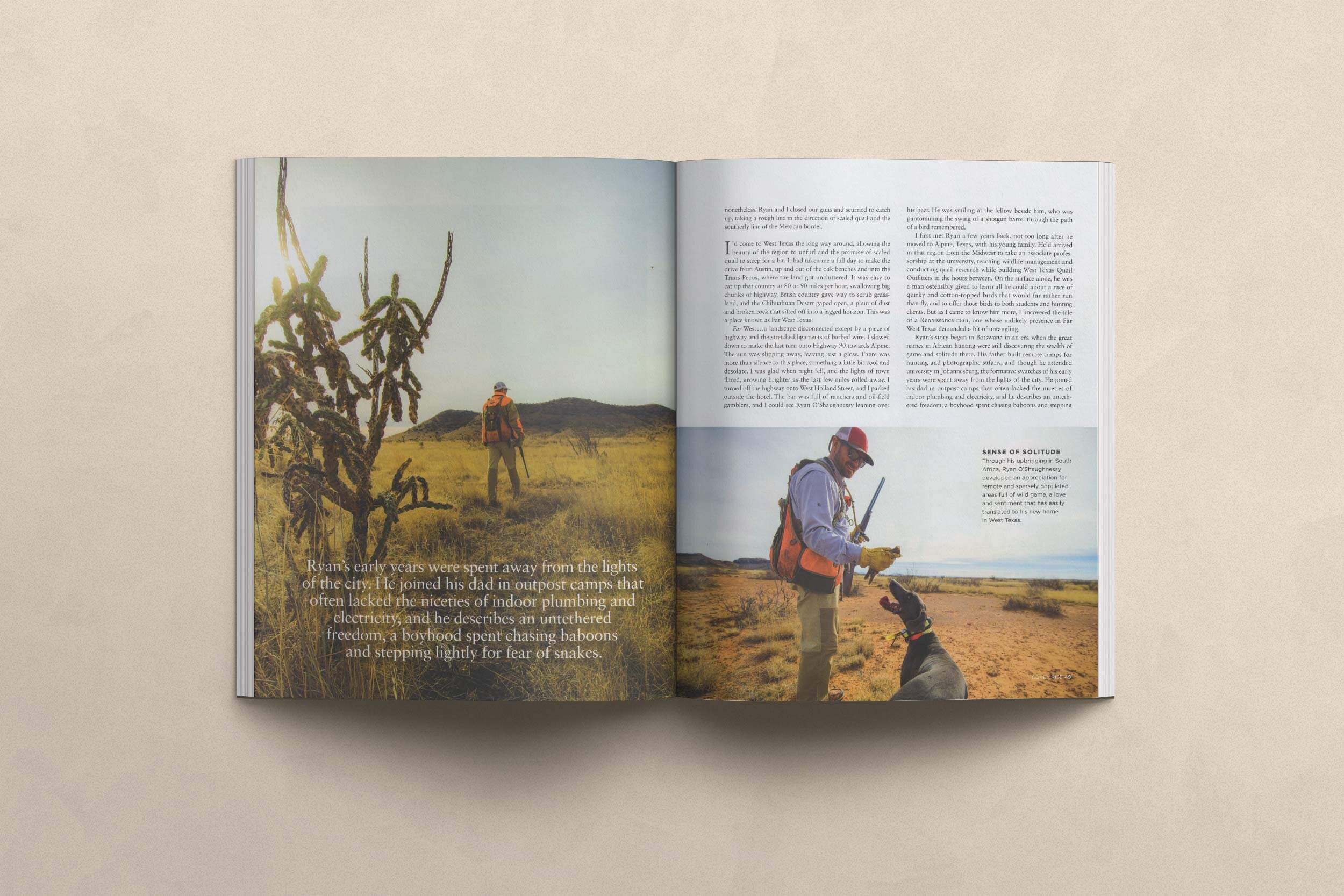

Ryan’s story began in Botswana in an era when the great names in African hunting were still discovering the wealth of game and solitude there. His father built remote camps for hunting and photographic safaris, and though he attended university in Johannesburg, the formative swatches of Ryan’s early years were spent away from the lights of the city: he joined his dad in outpost camps that often lacked the niceties of indoor plumbing and electricity, and he describes an untethered freedom, a boyhood spent chasing baboons and stepping lightly for fear of snakes. All around him was the culture of Professional Hunters who’d known the severe beauty of the African bush, and who’d learned to carve out lives in its womb, alongside the animals who also thrived there.

Ryan’s boyhood taught him a good measure of self-sufficiency too. In the Kalahari camps Ryan learned to fix a diesel engine, to rough-plumb a hut, and to secure birds and buffalo for camp meat. He listened thoughtfully and entertained with trademark charm when the traveling safaris and their sports came through. He came to rely upon himself alone to get un-stuck from the predicaments that remote places present, as there was rarely anyone else to rely on. He once told me the tale of a day when, wading a floodplain flow in search of ducks, a python lurched from the water and took hold of his dog. “What do you do in that situation?” I’d asked, quite certain that nobody I’d yet to meet would have known how to react to such a turn of events. “Well,” said Ryan with a shy smile. “I punched the snake a few times in the head, shot its tail off, and when it let loose of the dog I broke its spine.” He then shrugged. “Heck, I loved that dog… I’d have hated to see him eaten…” He said this in an academic sort of way, as if in the moment we’d all come to the same logical course of action.

Ryan’ boyhood path wandered in and out of the African bush, and his varied talents evolved. He played rugby throughout his university matriculation and landed a spot on Botswana’s national side. He worked within the budding industry of professional hunting, while also pursuing a professional rugby career in Europe and Africa. He returned when he could to the Botswana of his youth, and he continued to nurture his love of birds and dogs and wild places. As he grew older, and the impacts of a many-years’ rugby career started to take their toll, Ryan O’Shaughnessy returned to the classroom, to dig deeper into the species and landscapes that had served as an anchor-point throughout his life. He went on to earn a PhD in zoology from Southern Illinois University Carbondale, with a dissertation focused on habitat selection by migrating waterfowl. In possession of this degree, Ryan and his family set out to find a place where the full depth and breadth of an uncannily diverse skill set could be fully actuated. This search ended in far west Texas, where Ryan took a post at Sul Ross State University as a post-doctoral research scientist, in a place not altogether dissimilar from the Botswana of his youth.

In the ensuing years, Ryan has worked on pronghorn, Mearn’s quail, Scaled quail, aoudad, waterfowl, and wetland related research projects. He is active in the Gamebirds of the World committee with Safari Club International, specifically as the chair of the African gamebirds section, and in this capacity, he reviews applications from hunters who are trying to enter their birds into the world record book. He was formerly a member of the SCI Foundation Conservation Committee and remains a member of Quail Forever and the Quail Coalition, and he serves as the treasurer for the Southwest Section of The Wildlife Society. An impressive resume, to say the least.

Despite its diversity and embedded adventure, a life such as Ryan’s constrains a man in a sense, making the workaday world somewhat tedious, by contrast anyway. In far west Texas, Ryan found work and study that inter-married big thoughts and dusty places and calloused hands. What he saw in West Texas was something akin to his childhood, plump little birds to chase through a desolate landscape and a job that allowed him to exercise his ingenuity and intellect. In the spirit of the African PH he began to offer West Texas and her quail to those who lack the starch to get out on the fringes to get intimate with either one.

I met Ryan in the bar of the Holland Hotel and we moved to a table and ordered gin and tonics, just like Selby and Ruark would have done. We caught up on work and family and turned to dogs and quail. I asked what the coming days might hold. “I won’t lie to you,” Ryan in said in that formal, English-y way of the southern African. “It has been a dry year, and the numbers aren’t what I’d thought. We’ll hope to see a few coveys, but I can’t promise anything…” With that, he raised a glass.

Despite Ryan’s qualification of what we might not realize, I was quite happy to wander a bit deeper into the rough country that loomed out there in the dark, especially alongside someone who’d become a part of that landscape.

*

Over the days that followed we walked over cobbles of volcanic rock, chasing coveys of scalies that skittered through the scrub, appearing and dissolving into nothing, as wild quail are wont to do. We shot at birds as they popped from what appeared to be bare ground, with Ryan slowing to pull cholla spines from the dogs’ hardened feet. We covered miles, twisting down ranch roads into places where a broken axle or a broken ankle would have been consequential. As we did, Ryan showed me the nests of the cactus wrens, the soft green forbs that the quail had scratched and eaten, and the prints of a bobcat and elk in the dust. It became increasingly wonderful that a man several thousand miles from his homeland could have become so settled in this hardscrabble place.

As with all good things, the hours passed too quickly. The quail were there for the finding and we found our share, but we earned every last one. The final covey of the last day took some doing. We’d parked the jeep by a fence line in a hollow piece of ground thick with all-thorn branches and the serrated leaves of the yucca, and Ryan put down his team of English pointers. There was a rocky knob to our south, and the swelling of ground at the base of it was all baseball-sized rocks that rolled underfoot. I’d begun to regret my choice of thin-soled boots.

“There’s another good covey here,” offered Ryan, likely noting that the day had grown long, and I had grown tired, and in hunting it is often hope that compels us on. “I bet it’s thirty birds or more, and we haven’t shot at them yet…”

I was still good for another one. Ryan’s older pointer Citori sliced up the parcel in wide sweeps while the younger one, Covey, danced behind taking cues and flashing into an approximation of a point when the meadowlarks flittered away.

We struck the covey among the cobbles, having seen them up ahead through the cholla, dodging into hummocks of desert grass. We lit out for the runners and did not consider the lay birds that in turn popped like corn from the broken hillside. I took a left-to-right crosser and dropped it clean and turned to see Ryan swing through a double and poke them out of the afternoon sky. We ejected our shells and didn’t re-load, and the young pointer looked altogether sheepish at the praise she got upon the retrieve.

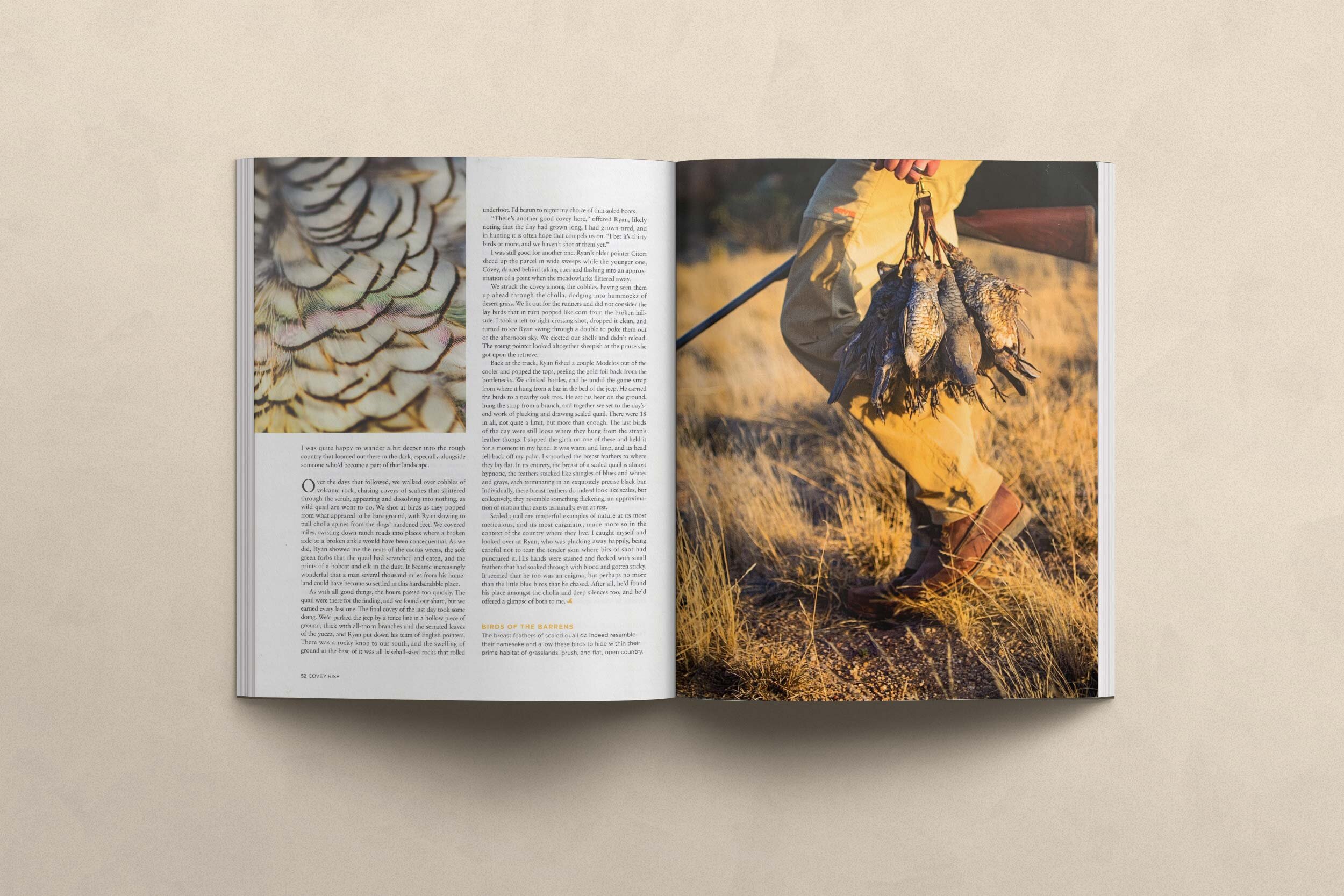

Back at the truck, Ryan fished a couple Modelo’s out of the cooler and popped the tops, peeling the gold foil back from the bottlenecks. We clinked bottles, and Ryan undid the game strap from where it hung from a bar in the bed of the jeep. He carried the birds to a nearby oak. He set his beer on the ground and hung the strap from a branch, and together we set to the day’s-end work of plucking and drawing scaled quail. There were eighteen in all, not quite a limit but more than enough, the last birds of the day still loose where they hung from the strap’s leather thongs. I slipped the girth on one of these and held it for a moment in my hand. It was warm and limp, and its head fell back off my palm. I smoothed the breast feathers to where they lay flat. In its entirety, the breast of a scaled quail is almost hypnotic, the feathers stacked like shingles of blues and whites and grays, each terminating in an exquisitely precise black bar. Individually these breast feathers do indeed look like scales, but collectively like something flickering, an approximation of motion that exists terminally, even at rest. Scaled quail are masterful examples of nature at its most meticulous, and its most enigmatic, made more so in the context of the country where they live. I caught myself and looked over at Ryan, who was plucking away happily, being careful not to tear the tender skin where bits of shot had punctured it. His hands were stained and flecked with small feathers that had soaked through with blood and gotten sticky. It seemed that he too was an enigma, but perhaps no more than the little blue birds that he chased. After all, he’d found his place amongst the cholla and deep silences too, and he’d offered a glimpse of both to me.

First published in Covey Rise August/September 2019