A Meditation on Golden Retrievers

My friend Stephen Prout grew up on Abbott Road in Wellesley, a few miles west of Boston. His family owned a grand brick home set back from the sidewalk, bounded on the road side by a surgically maintained privet hedge. The front lawn was flat and rectangular, long enough that a 4th grader with a decent arm could drop back onto the driveway and let fly with a nerf football, hoping barely to reach a receiver crossing the woods-line opposite. The neighborhood kids had epic games out there: two-hand touch was the rule, but it always seemed someone would get a little too enthusiastic, and someone else would wind up with a nosebleed. At mostly nine and ten we were young enough to view crying as permissible, provided it was not heard by Mrs. Prout, who would emerge from the kitchen and summarily put an end to our game.

Throughout those days on the Prout’s front lawn, our only audience was a placid Golden Retriever named Breezemere, who watched us from the open back hatch of the family’s Grand Wagoneer. Breezy bore witness to our wins, losses, and occasional tears. She lay there and panted through our games, snoozing on outstretched legs as the one-Mississippi, two-Mississippi counts rang out. She kept a slimy tennis ball close, and she never really went anywhere, or interfered with our back and forth. I suppose the confines of a small, suburban life suited her. It must have been a comfort to be absolutely satisfied with an existence so mundane.

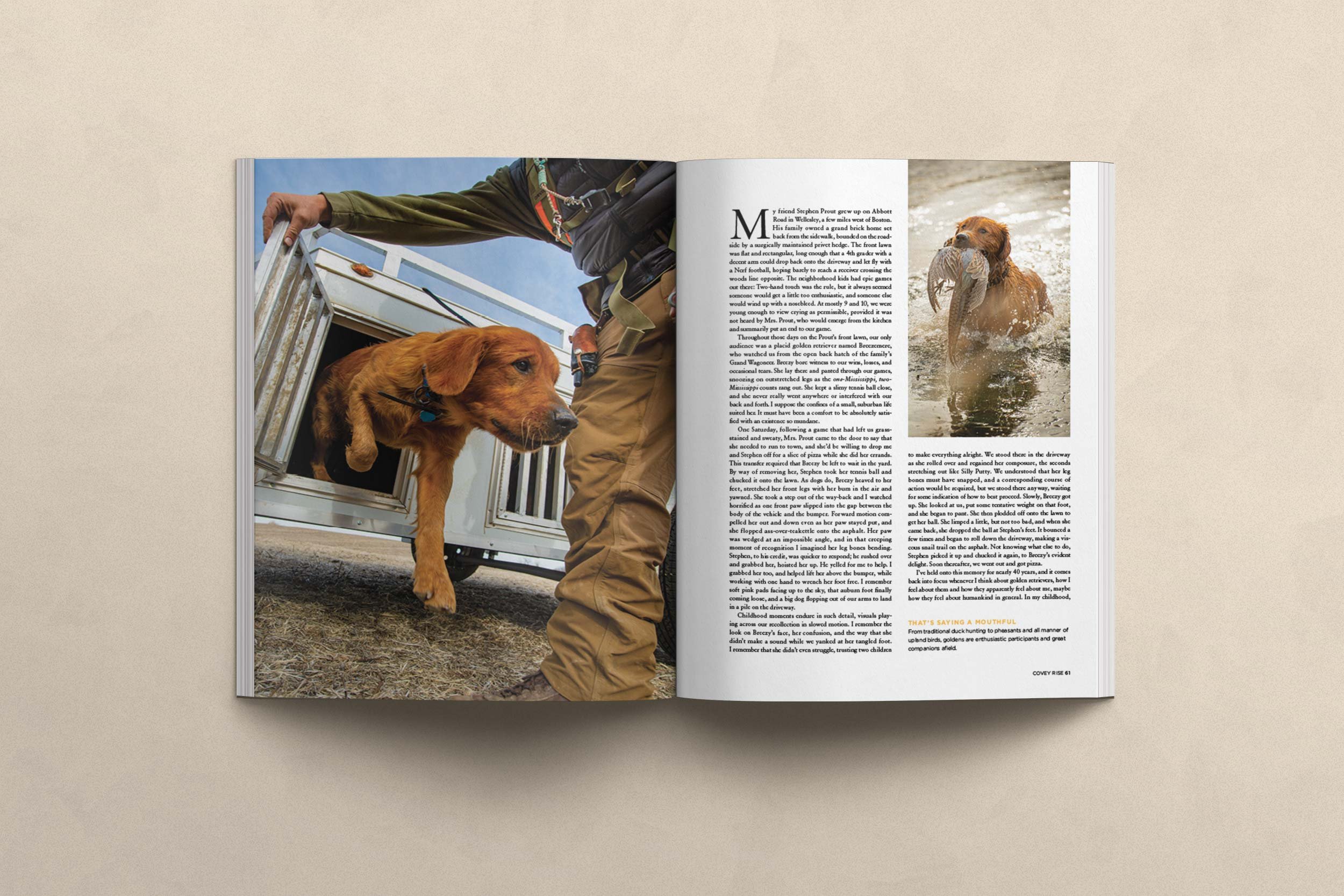

One Saturday, following a game that had left us grass-stained and sweaty, Mrs. Prout came to the door to say that she needed to run to town, and she’d be willing to drop me and Stephen off for a slice of pizza while she did her errands. This transfer required that Breezy be left to wait in the yard. By way of removing her, Stephen took her tennis ball and chucked it onto the lawn. As dogs do, Breezy heaved to her feet, stretched her front legs with her bum in the air and yawned. She took a step out of the way-back and I watched horrified as one front paw slipped into the gap between the body of the vehicle and the bumper. Forward motion compelled her out and down even as her paw stayed put, and she flopped ass-over-teakettle onto the asphalt. Her paw was wedged at an impossible angle, and in that creeping moment of recognition I imagined her leg bones bending. Stephen, to his credit, was quicker to respond; he rushed over and grabbed her, hoisted her up. He yelled for me to help. I grabbed her too, and helped lift her above the bumper, while working with one hand to wrench her foot free. I remember soft pink pads facing up to the sky, that auburn foot finally coming loose, and a big dog flopping out of our arms to land in a pile on the driveway.

Childhood moments endure in such detail, visuals playing across our recollection in slowed motion. I remember the look on Breezy’s face, her confusion, and the way that she didn’t make a sound while we yanked at her tangled foot. I remember that she didn’t even struggle, trusting two children to make everything alright. We stood there in the driveway as she rolled over and regained her composure, the seconds stretching out like silly putty. We understood that her leg bones must have snapped, and a corresponding course of action would be required, but we stood there anyway, waiting for some indication of how to best proceed. Slowly, Breezy got up. She looked at us, put some tentative weight on that foot, and she began to pant. She then plodded off onto the lawn to get her ball. She limped a little, but not too bad, and when she came back, she dropped the ball at Stephen’s feet. It bounced a few times and began to roll down the driveway, making a viscous snail trail on the asphalt. No knowing what else to do, Stephen picked it up and chucked it again, to Breezy’s evident delighted. Soon thereafter, we went out and got pizza.

I’ve held onto this memory for nearly forty years, and it comes back into focus whenever I think about Golden Retrievers, how I feel about them and how they apparently feel about me, maybe how they feel about humankind in general. In my childhood, Goldens like Breezy were ubiquitous. They were a piece of the suburban aesthetic, adjacent to an outdoorsy identity but of no greater measurable utility than that. Those dogs did not hunt, but the fact that their forefathers did earned them some social currency: as a sporting breed they were descriptive of the lifestyle that their owners aspired to convey without actually having to visit untamed places. They were, to a dog, happy and easy and uncomplicated, game for any activity wet or dry. Those Goldens didn’t ask a whole lot, but they offered identity and love in volume. That’s how I came to know Goldens. Even now, a mention of the breed triggers memories of grass-stained knees and tennis balls and LL Bean boots, rather than days afield and duck blinds and cock pheasants. I know they hunt… I’ve seen it. But Goldens remain for me something slightly other, residents of my boyhood landscape rather than residents of those I frequent now in boots and brush pants.

The intellectual compartmentalization of a breed begs some self-examination. In the years since 4th grade, I’ve come to view sporting dogs as something purposeful. Maybe I denigrate dogs by looking at them thus: what actions they are quantifiably capable of and to what degree. This qualification induces prejudice, and sells some individual critters short. But I somehow also remain grateful for the context by which I came to an understanding of Golden Retrievers, and the facets of the breed that persist both in and out of the field. A decade after Breezy’s tumble, in my later teens, gundogs became inhabitants of a new and consequential space. In this space I created a line of demarcation as distinct as the Prout’s privet hedge, on one side of which were dogs with drive and style compelled by something deeper than any desire to please me. These dogs were motivated by a higher power; there were points to hold and retrieves to complete, manifestations of a genetic necessity. Somehow, I became aware that I had relegated Goldens to the other side of that privet hedge, where they remained happily in a suburban ideal. So, as I encountered them in the field, some great ones too, their greatness would be measured against uncertain metrics. Their value was foremost felt in their attitude of approach, one laid out in purest form by Tim and Joanne Linehan’s Gracie, a dog for whom I reserve a special place in my heart.

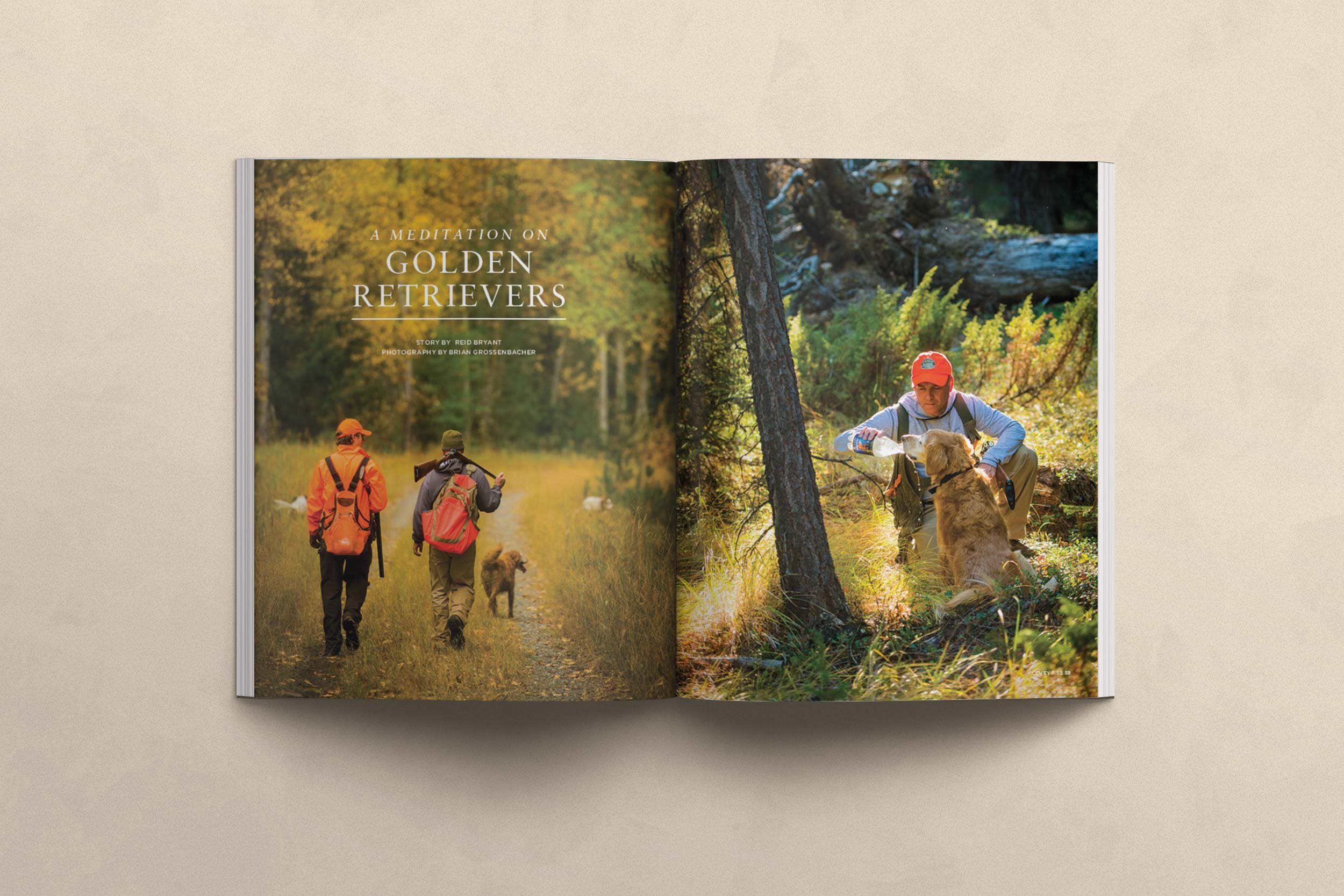

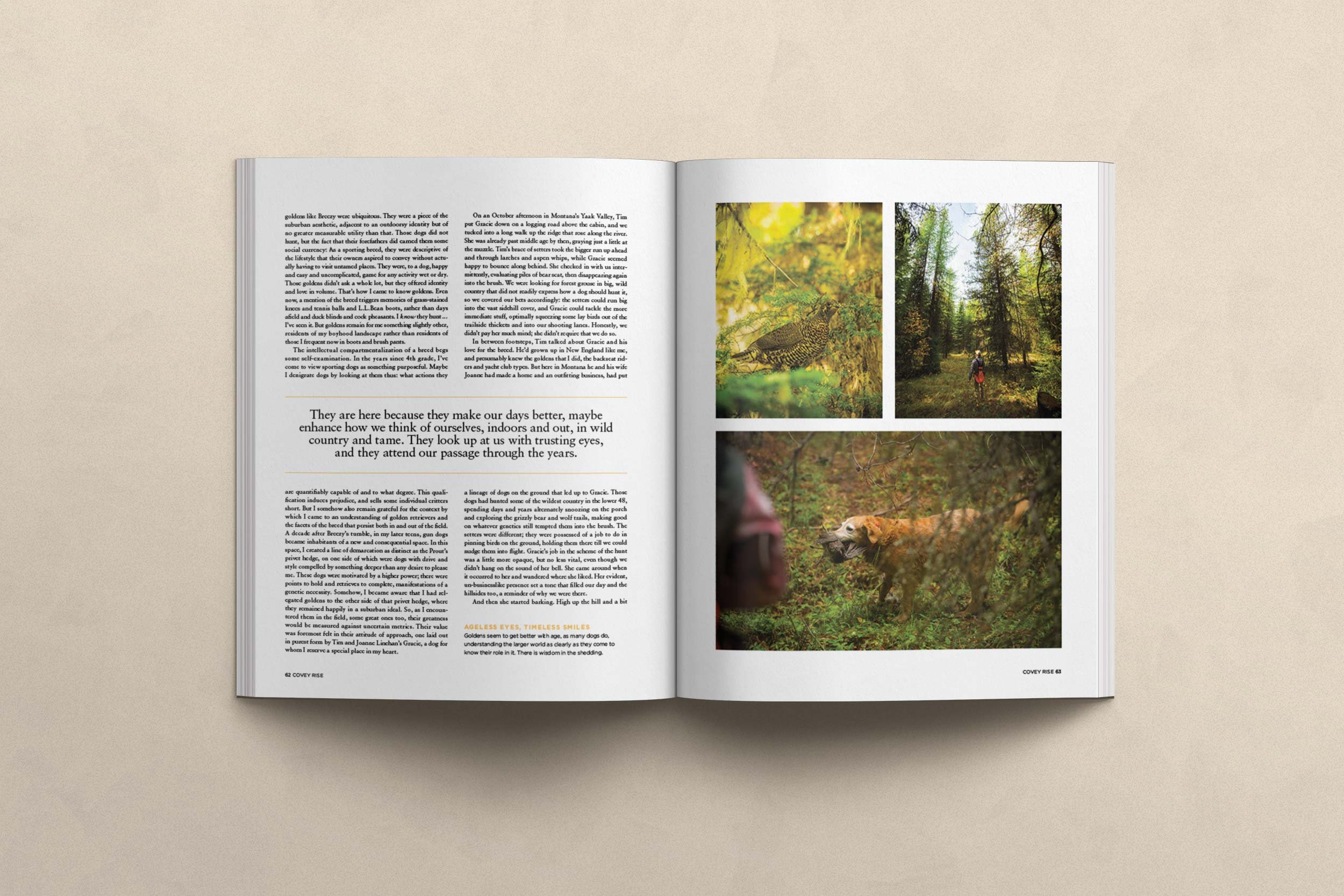

On an October afternoon in Montana’s Yaak Valley, Tim put Gracie down on a logging road above the cabin, and we tucked into a long walk up the ridge that rose along the river. She was already past middle age by then, graying just a little at the muzzles. Tim’s brace of setters took the bigger run up ahead and through larches and aspen whips, while Gracie seemed happy to bounce along behind. She checked in with us intermittently, evaluating piles of bear scat, then disappearing again into the brush. We were looking for forest grouse in big, wild country that did not readily express how a dog should hunt it, so we covered our bets accordingly: the setters could run big into the vast sidehill cover, and Gracie could tackle the more immediate stuff, optimally squeezing some lay birds out of the trailside thickets and into our shooting lanes. Honestly, we didn’t pay her much mind; she didn’t require that we do so.

In between footsteps, Tim talked about Gracie, and his love for the breed. He’d grown up in New England like me, and presumably knew the Goldens that I did, the back-seat riders and yacht club types. But here in Montana he and his wife Joanne had made a home and an outfitting business, had put a lineage of dogs on the ground that led up to Gracie. Those dogs had hunted some of the wildest country in the lower 48, spending days and years alternately snoozing on the porch and exploring the grizzly bear and wolf trails, making good on whatever genetics still tempted them into the brush. The setters were different; they were possessed of a job to do in pinning birds on the ground, holding them there till we could nudge them into flight. Gracie’s job in the scheme of the hunt was a little more opaque, but no less vital, even though we didn’t hang on the sound of her bell. She came around when it occurred to her, and wandered where she liked. Her evident, un-businesslike presence set a tone that filled our day and the hillsides too, a reminder of why we were there.

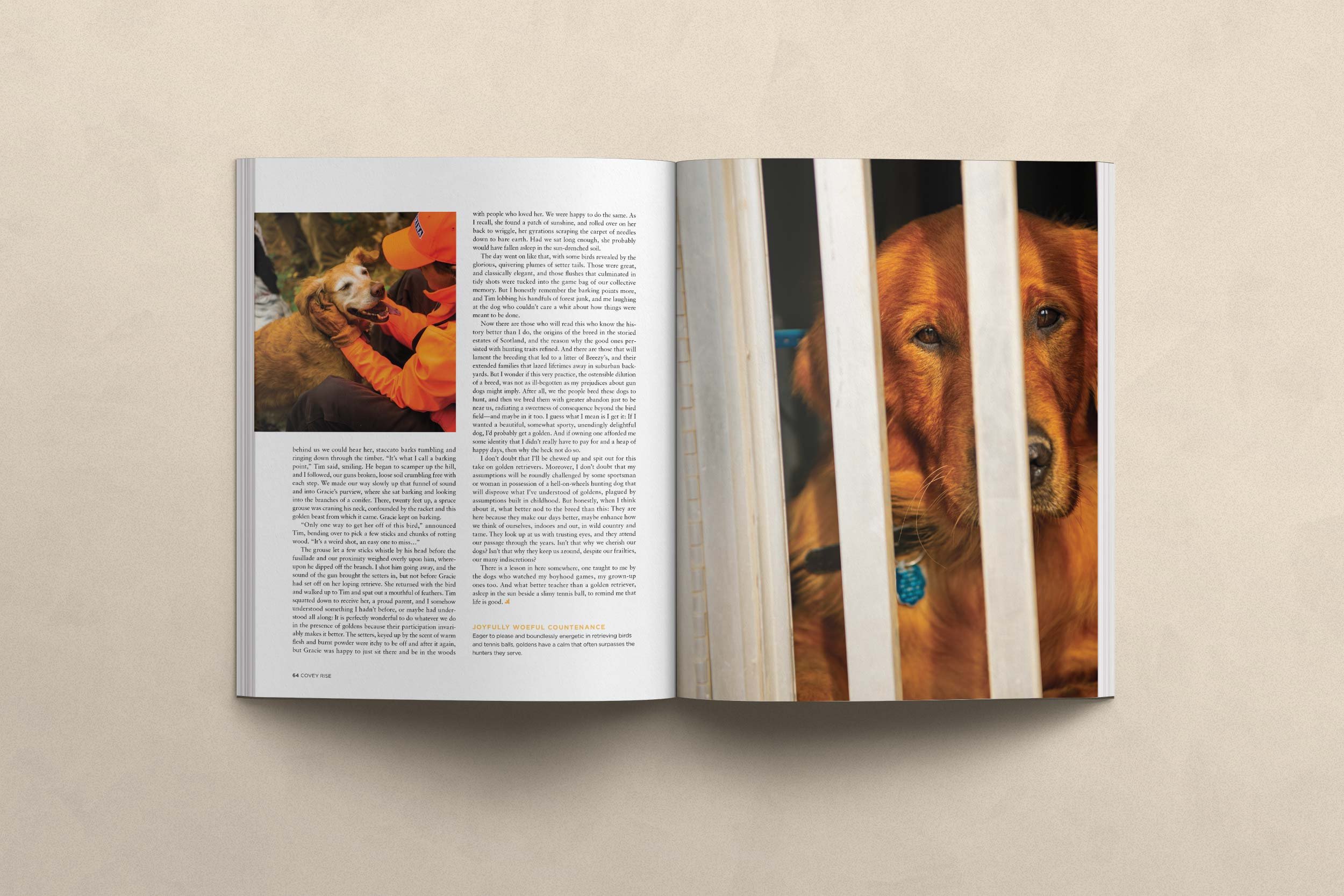

And then she started barking. High up the hill and a bit behind us we could hear her, staccato barks tumbling and ringing down through the timber. “It’s what I call a barking point,” Tim said, and smiled. He began to scamper up the hill, and I followed, our guns broken, loose soil crumbling free with each step. We made our way slowly up that funnel of sound and into Gracie’s purview, where she sat barking and looking into the branches of a conifer. There, twenty feet up, a spruce grouse was craning his neck, confounded by the racket and this golden beast from which it came. Gracie kept on barking.

“Only one way to get her off of this bird,” announced Tim, bending over to pick a few sticks and chunks of rotting wood. “It’s a weird shot, an easy one to miss…”

The grouse let a few sticks whistle by his head before the fusillade and our proximity weighed overly upon him, whereupon he dipped off the branch. I shot him going away, and the sound of the gun brought the setters in, but not before Gracie had set off on her loping retrieve. She returned with the bird and walked up to Tim and spat out a mouthful of feathers. Tim squatted down to receive her, a proud parent, and I somehow understood something I hadn’t before, or maybe had understood all along: it is perfectly wonderful to do whatever we do in the presence of Goldens because their participation invariably makes it better. The setters, keyed up by the scent of warm flesh and burnt powder were itchy to be off and after it again, but Gracie was happy to just sit there and be in the woods with people who loved her. We were happy to do the same. As I recall, she found a patch of sunshine, and rolled over on her back to wriggle, her gyrations scraping the carpet of needles down to bare earth. Had we sat long enough, she probably would have fallen asleep in the sun-drenched soil.

The day went on like that, with some birds revealed by the glorious, quivering plumes of setter tails. Those were great, and classically elegant, and those flushes that culminated in tidy shots were tucked into the game bag of our collective memory. But I honestly remember the barking points more, and Tim lobbing his handfuls of forest junk, and me laughing at the dog who couldn’t care a whit about how things were meant to be done.

Now there are those who will read this who know the history better than I do, the origins of the breed in the storied estates of Scotland, and the reason why the good ones persisted with hunting traits refined. And there are those that will lament the breeding that led to a litter of Breezy’s, and their extended families that lazed lifetimes away in suburban backyards. But I wonder if this very practice, the ostensible dilution of a breed, was not as ill-begotten as my prejudices about gundogs might imply. After all, we the people bred these dogs to hunt, and then we bred them with greater abandon just to be near us, radiating a sweetness of consequence beyond the bird field, and maybe in it too. I guess what I mean is I get it: if I wanted a beautiful, somewhat sporty, unendingly delightful dog, I’d probably get a Golden. And if owning one afforded me some identity that I didn’t really have to pay for, and a heap of happy days, then why the heck not do so.

I don’t doubt that I’ll be chewed up and spit out for this take on Golden Retrievers. Moreover, I don’t doubt that my assumptions will be roundly challenged by some sportsman or woman in possession of a hell-on-wheels hunting dog that will disprove what I’ve understood of Goldens, plagued by assumptions built in childhood. But honestly, when I think about it, what better nod to the breed than this: they are here because they make our days better, maybe enhance how we think of ourselves, indoors and out, in wild country and tame. They look up at us with trusting eyes, and they attend our passage through the years. Isn’t that why we cherish our dogs? Isn’t that why they keep us around, despite our frailties, our many indiscretions?

There is a lesson in here somewhere, one taught to me by the dogs who watched my boyhood games, and my grown-up ones too. And what better teacher than a Golden Retriever, asleep in the sun beside a slimy tennis ball, to remind me that life is good.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine