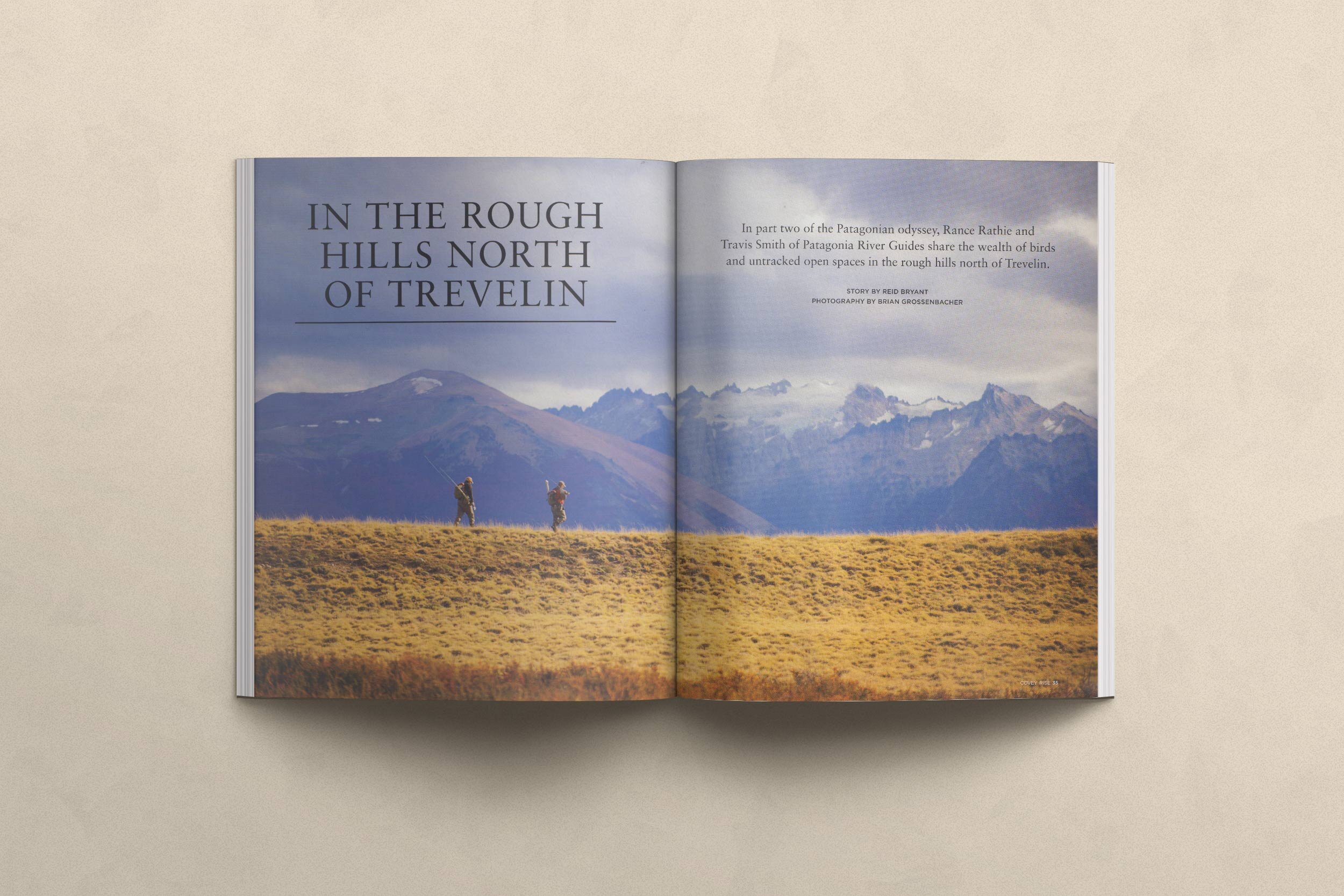

In the Rough Hills North of Trevelin

In 1901, Robert Leroy Parker and Harry Alonzo Longabaugh boarded the British ship Herminius under assumed names. Parker and Longabaugh were traveling in the company of a young woman of unusual good looks, whose given name was Etta Place. The trio set out under steam from New York City, journey-bound for the port at Buenos Aires, where the men had arrangements to secure ranchland and livestock. In their possession were several tens of thousands of US dollars, and an already-cemented reputation as among the most storied outlaws of the American West. Then as now, they were far better known respectively as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

For several years prior, Parker and Longabaugh had been increasingly under the eye of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, who suspected them of a series of bank and train robberies in Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, and Utah. With hideouts and conspirators scattered across desolate stretches of the western range, the duo had ostensibly lived like rogues: they were flush with cash, untethered and seemingly untouchable, as at home under the unbroken sweep of desert sky as they were in the starched front-street parlors of Denver and Fort Worth. They managed somehow to evade Pinkerton in a years-long game of cat and mouse before the agency, no doubt incensed at being outmaneuvered, redoubled its focus. It was thus that Parker, Longabaugh, and the fair Etta Place boarded a ship in New York harbor, slipping off into a world that was, by all accounts, their oyster.

Perhaps what compels us still in the story of Butch and Sundance, indeed what supplants the actuality of their crimes, is the fairytale way in which they danced through a life unbounded. They were young and charming, wanting for nothing but a bigger piece of ground to roam, leaving little of consequence to stir them towards nostalgia. I’d even venture that their departure for Argentina was less an escape and more a valediction: they’d whupped an America that was still quite wild, and found themselves in need of something wilder. With the whole world at their disposal, they set their course by the Southern Cross to a place altogether familiar, but thousands of miles from home.

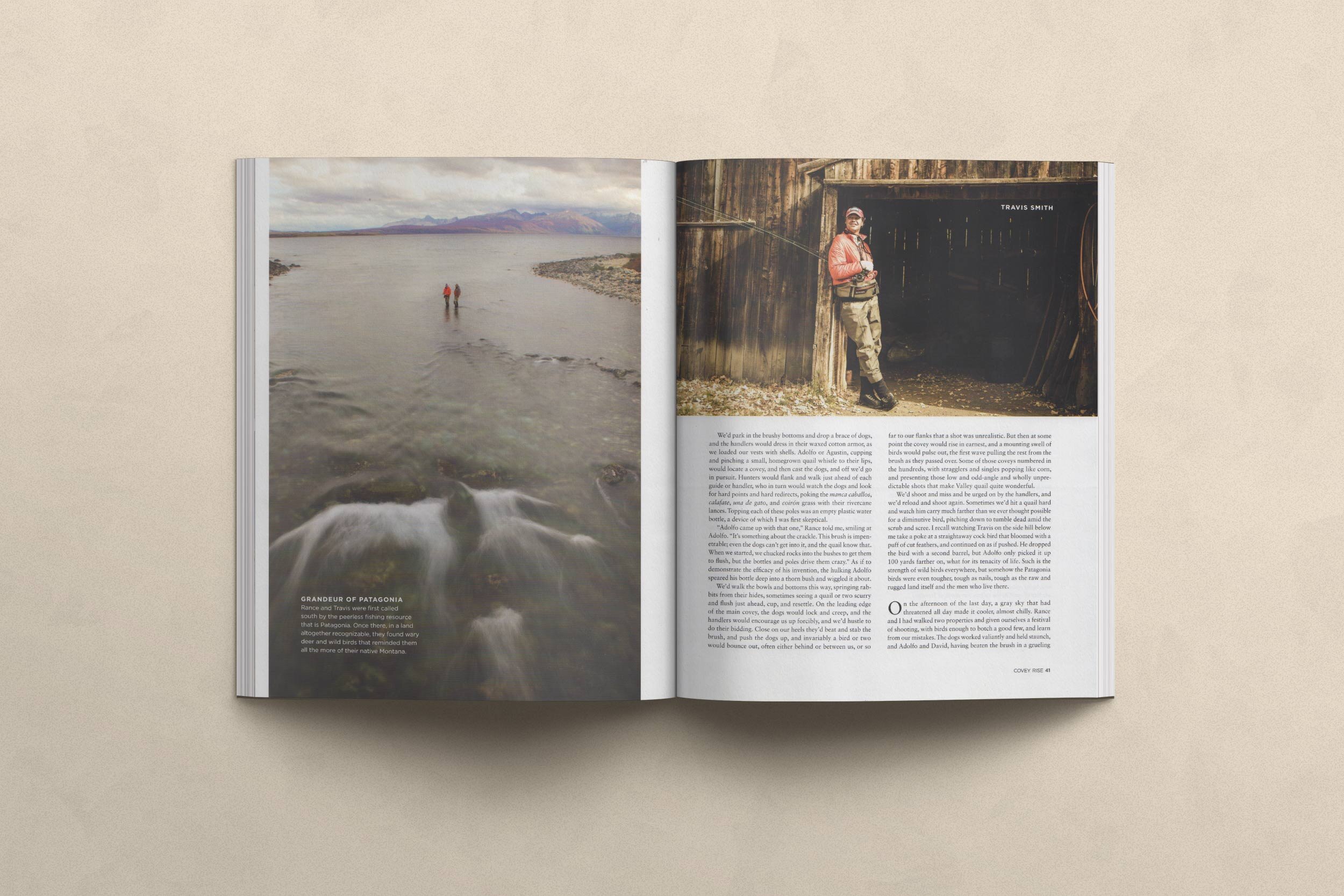

In central Patagonia, mile after mile of steppe grassland and desert falls away from the snow-capped spine of the Andes. It is a vast and unexploited swatch of scree and catclaw and cold-running rivers, of sheep and cattle and cowboys. In 1901 it was all the more so, a desolate land into which a man might disappear forever, and where any man, especially a gringo, was something of a peculiarity. But central Patagonia is where Butch and Sundance and Etta Place finally landed, and the region from which they at length disappeared. On the valley flatlands in the province of Chubut they built up a small ranch, drank a bit of wine with the local gauchos, ran cattle and horses and sheep through a plain outwardly reminiscent of Wyoming or Montana, but far less tracked. Patagonia proved itself a place wherein two men for whom the wild west was a bit too tame could roam a bit, and lose themselves in the shadow of mountains. It is not lost on history, though, that other men have found the same escape, and perhaps the same dreamed-of magnificence, in those rough hills north of Trevelin.

*

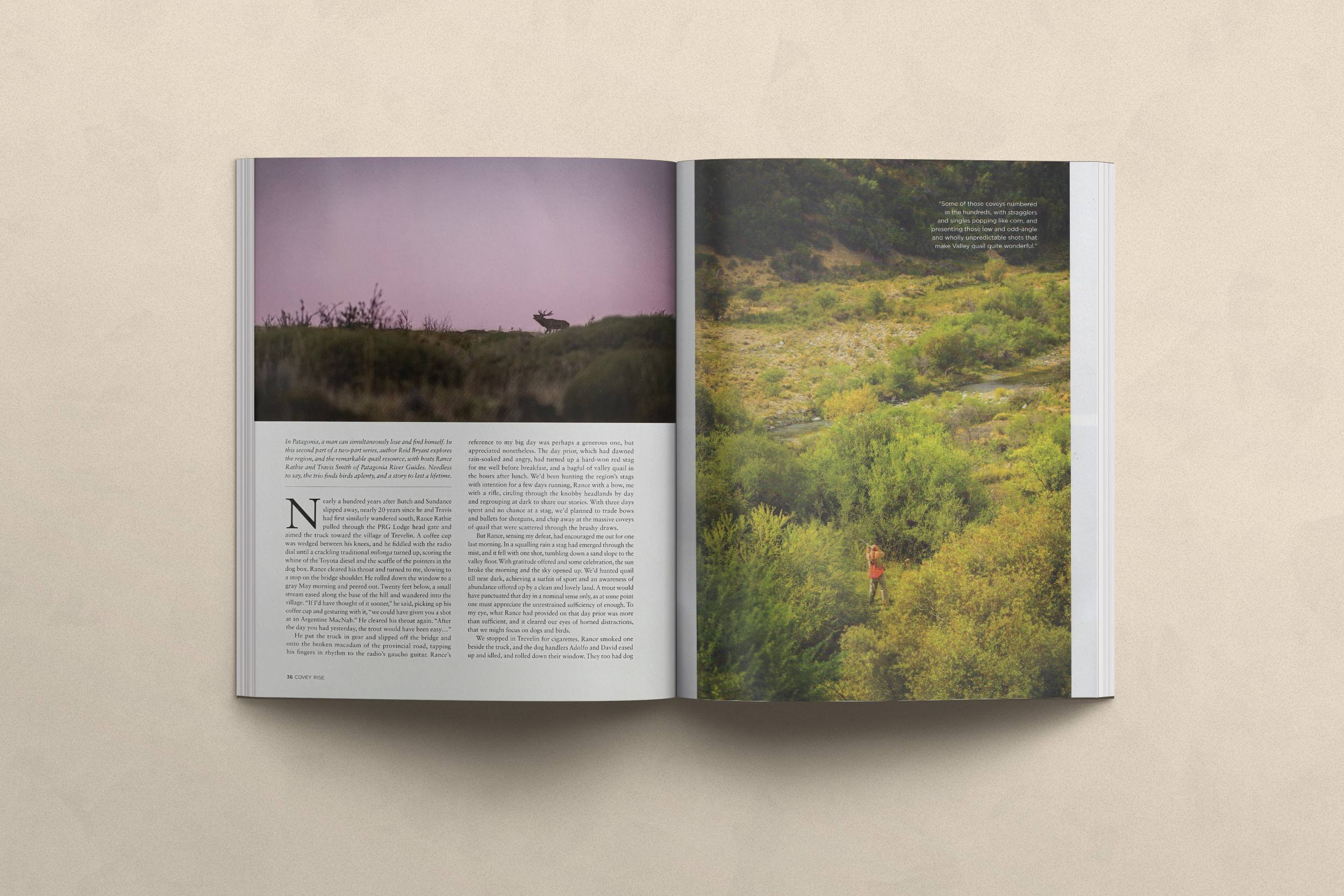

Nearly a hundred years later, I found myself in those same rough hills, leaning into the curve as the rear wheels of the truck drifted the last hard corner of the provincial road, kicked a plume of dust, and geared down onto the rutted two track. Spreading out before us was an endless plateau splotched with brush. It was a landscape giving itself away to autumn, the light low and hard, turning clumps of sunburnt grass and scrub to gold. Against the near ridge, bluff and scree defined a band of shadow and green, a ribbon of winking silver, which substantiated the valley of El Rio Corintos. Somewhere in the indistinct margins of the river was our destination, and ostensibly a covey of quail the likes of which I’d never even imagined.

We stopped at a ranch gate, and Travis Smith handed a fresh charge of maté to my friend Agustin Bustos in the passenger seat. Being the back-seat rider, I hopped out. A twist of rusted wire and wood were woven into a contrivance of tension and torque. I sprung the gate and dragged it inward, letting the truck pass through. As it idled, I tried in vain to re-fix the gate, to recreate with my pale hands a puzzle-piece of gaucho ingenuity. I failed marvelously, and in the side mirror I saw Travis giggling. Agustin at length relieved the agony of my ineptitude. In characteristic calm, he took the gatepost and nodded me back to the truck. “I got it,” he said. I smiled sheepishly, and thanked him. He cocked the gate back to pinging tight, and I got back in my seat, inwardly pledging that I’d show ‘em all once the dogs were down, and the moments of truth came to pass.

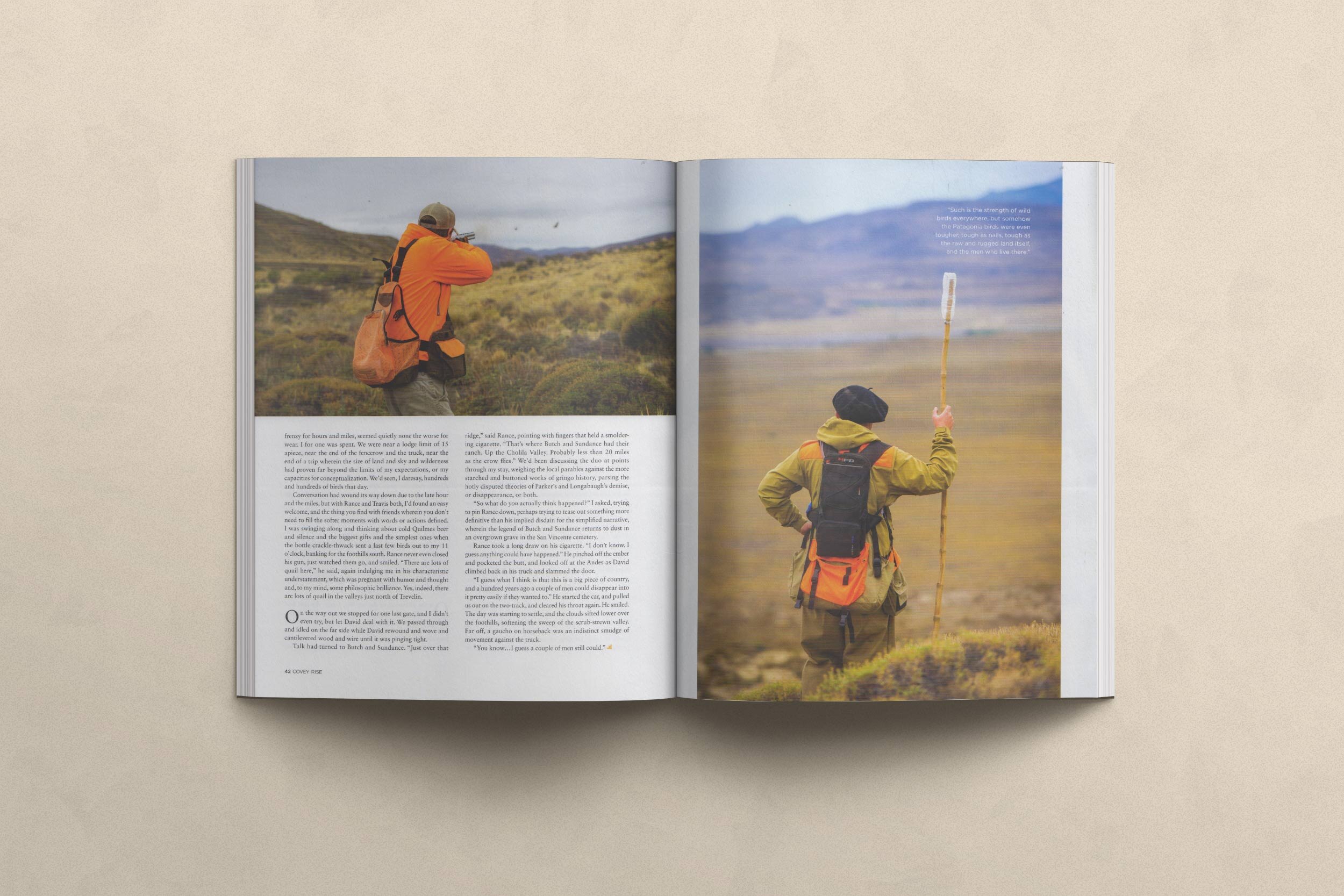

At the shoulder of the plateau we banked right and Travis shifted again, easing over the lip and down to the valley floor. Much compressed against the final approach, the engine whined, and so did the dogs. Travis pulled onto the level and eased to a stop in the grassy edge of the two-track. He backed the truck and the dog boxes into a sliver of shade and cut the engine. The dogs continued to whine. In the stillness of the ascending day, the sun got higher and hotter, and the Rio Corintos glittered in full freestone brilliance below us. The dogs were whimpering in earnest now, three Elhew pointers in their boxes who seemed to recognize the texture of this place. Agustin quieted them. He took one then the next from their boxes and spoke to them in gentle Spanish, patting their heads, checking their eyes, putting a collar onto each and sending them off for an air-out. They made the cursory tour of the vicinity while we laced our boots and loaded our vests with shells and water, pulled buffs up high on our necks and anointed our noses with sunscreen. Agustin and his fellow handler Alejandro Jones each took a long cane pole from the truck bed, and affixed a spent plastic water bottle to the tip. I looked out at the upstream valley, which seemed a labyrinth of thicket and draw, scree slope and spring bottom. Travis pulled on a pair of chaps that were torn near to shreds, proof of the country. I looked down at my thin brush pants and hoped for the best.

“We usually have a covey here,” Travis said smiling, while Agustin pulled from his pocket a homemade quail whistle and took a few steps closer to the river. He put the call to his lips, and blew gently. A kazoo-like oration of questioning notes squalled out through the valley. “Hee-HEEE-he…” said Agustin’s call, and “Hee- HEEE-he….” once more. The sound was nearly swallowed by the space and the water. Agustin cocked his head and listened. He pointed off across the valley, in the direction of the muted echo of response, which wonderfully I had heard too. Travis looked out towards the jagged skyline ridge absently, eyes sparkling, and smiled. A few hundred yards out, across the chime and gurgle of the Corintos, a handful of valley quail were calling back, answering Agustin’s masquerade, and putting a fresh and stirring wrinkle on our prospects for the day.

*

I’d come to Argentina not for the much-celebrated doves or ducks or perdiz, but for California Valley Quail, Callipepla californica, the elusive and top-knotted dynamos that I’d hunted from Washington to Baja and points between. In the scrub valleys of the Patagonian steppe, a burgeoning but largely unknown population of quail has erupted over the past forty years, and I had it on good authority that those in search of wild birds in wild country might find a wealth of both in that land far south. That I loved these birds, and their propensity to sift wraithlike through the foothill cover, was, however, something of a secondary motivation. I’d also come to once more see my friend Agustin Bustos, who, in the employ of Patagonia River Guides, had brought his dog string west from the perdiz fields of Entre Rios to chase the fortunes of Patagonian quail. I’d come of course for wine and grilled meat and an autumn in May, and the chance to carry a shotgun through a place unsullied and untracked.

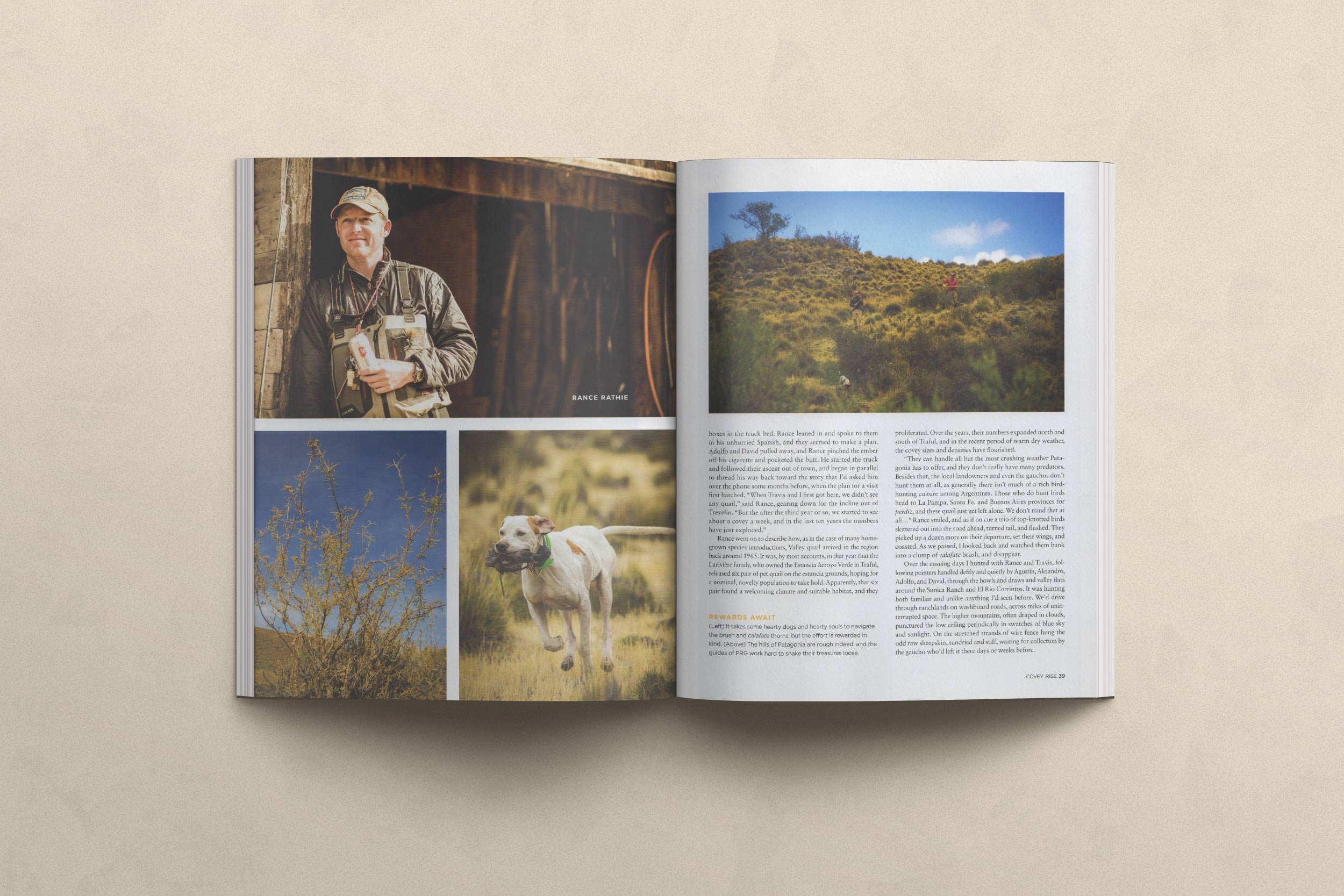

But really come I’d come for a story, one so oddly reminiscent of a wild-west folktale that it could not have been orchestrated. Mine was the search for the tale of Rance Rathie and Travis Smith, two men who, much like Butch and Sundance, had left an American west that was a little too tame, and found a cascade of merciless country spilling off the east slope of the Andes. Despite our shared proclivities for birds and trout and mountain deer and pointing dogs, I could tell from the start that those things were just context, an academic excuse for Rance and Travis to be in this place, weaving themselves into a life in what remains a frontier, so full of open space and opportunity it’s a little bit daunting, and a little bit lonesome, just as any cowboy ballad would hope it to be.

*

Rance and Travis grew up best friends in Sheridan, Montana, a town of six hundred nestled solidly in the heart of the finest hunting and fishing in the lower 48. Small-town kids with a nose for adventure, they’d cut their teeth and hardened their hands fishing the storied waters of the Ruby, the Big Hole, the Beaverhead. As the seasons shifted they’d hunted elk and deer in the timber of the Tobacco Roots, chased grouse and pheasants in the foothill margins and the river breaks. By college age they were locally known as savants of a sort, as good if not a good bit better than any man in that Big Sky country, and uncannily adept at tying into that country’s fish and game. Rance, in characteristic understatement, puts it thus: “Together, we tried to shoot and catch everything we could when we were growing up. It really just depended on what time of year it was…” Needless to say, they caught and shot quite a bit.

Following college, the two shared an apartment in Missoula. Rance had been working towards a career as an environmental engineer within the timber industry, and Travis was navigating the options for extending a fish guiding summer up against a ski season in Jackson Hole. Seemingly, though, the two were itching for something a bit more rugged, a bit more raw, something less restrained than seasonal work on the rivers and timberlands of the Rocky Mountain west. Over a series of beers and evenings, they thumbed through the fly-fishing magazines and discussed the possibility of trying to land jobs in the sporting mecca of Argentina, guiding the long winter (Argentine summer) season on the Andean trout streams of Patagonia. With a singleness of purpose that defines him still, Rance went looking for an opportunity, and found one at the fly tackle dealers trade show in Denver. There he met John Roberts, an Argentine gentleman who was managing a lodge in Chubut. Rance took a guiding job under Roberts and scouted the opportunities, returning the next year with Travis. In the seasons that followed, they cemented such a reputation as guides and anglers and all-around guys in-the-know that their clients came to summarize the ultimate Patagonian angling adventure by simply saying “I fished with Rance n’ Travis”. It’s a statement that to this day seems to sum it all up.

In 2001, Rance and Travis started their own business, namely Patagonia River Guides (PRG), with the focus of putting the best guides and the best gear on the best rivers in central and northern Patagonia, surprising and delighting traveling sportsmen with the offering at every possible turn. In the years following they expanded their business throughout the region, buying and developing properties, leasing land and river access and enabling those with a penchant for wild fish and wild places to drink deeply of the region’s abundance of both. PRG added guided hunts for trophy red stag in the estancias around Trevelin, affording visiting sportsmen the opportunity to roam the timbered foothill lengas during the short but electric rutting season, known colloquially as the roar. They built a lodge in Trevelin the equal of which does not exist, and developed satellite lodges up and down the Andean steppe. In this way the drainages and ranchlands of Chubut province proved more abundant and untapped than anything in the American west, but around the edges of that there was something missing through the inverted Argentine seasons, some void in those spring/autumn months when the parched and golden landscape catches a lower slant of sun. It was in that season back in Montana that something always beckoned a fellow to take a dog and a gun and go for a good long walk, hopeful for a covey of birds but satisfied from the very start to be awash in open country. And then, as if the resource was deigned to accommodate them, somewhere in the mid 2000’s Rance and Travis began to hear a familiar call over the course of their river days, and through the happy silences of their shore lunches: “Hee-HEEE-he… Hee-HEEE-he… Hee-HEEE-he…” Fishing guests took notice.

First published in Covey Rise