In Praise of English Pointers

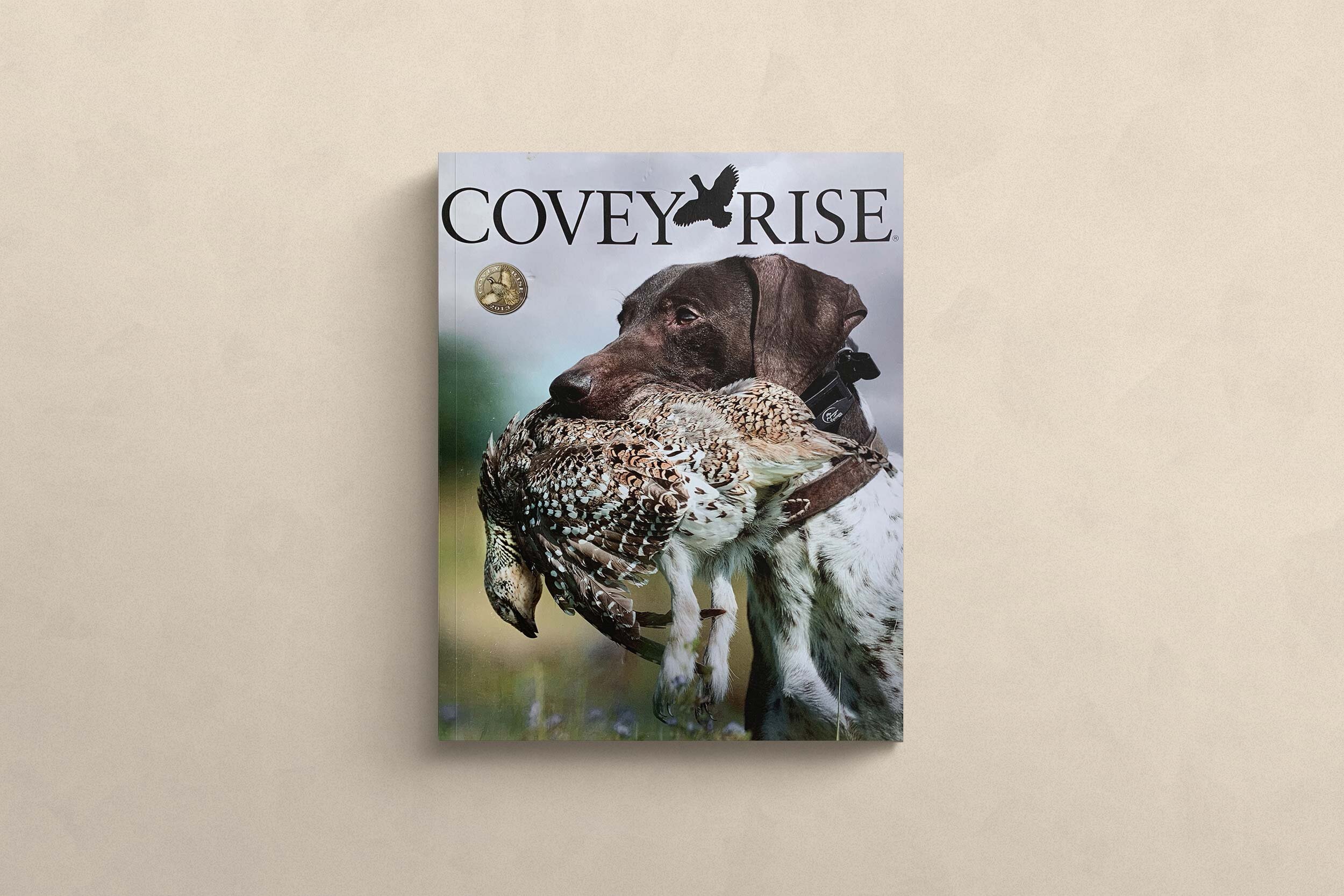

To see an English Pointer at work, to see one quarter a grain field and slam into scent, becoming a frozen moment with a whip-tall tail, is to see a pointing dog defined. In that frozen moment, it all becomes plain: movement suspended in a still life of absolute anticipation. There may be more beautiful things in this world than a block-headed bird dog with its chest on the ground, but I have yet to encounter one.

The first dog I ever hunted over was an English Pointer. She was a lemon and white bitch in the service of Tinmouth Hunting Preserve in southern Vermont. Her name was Belle. It’s quite possible that she understood the ruse, understood that there was something not quite real in the standing grain that cloaked the Vermont hillsides and brimmed over with planted Chukars. The birds I shot that day flushed against a razorback of New England color, and they seemed altogether confused by the absence of rimrock. Belle couldn’t have cared; when the dog box door opened, birds became her whole world. She ran herself ragged in pursuit of them, sucked up their scent, pinned them close, and turned a canned hunt into something transcendent. I fell in love with English Pointers that day.

The English Pointer is a masterpiece of breeding and refinement. Records of the bloodline date back to the mid 1600’s, to dogs selected for locating game in the moors of the British Isles. In their ancestral hunting grounds, English Pointers continue to point Red Grouse for walk-up gunners, but it is in the uplands of North America that they’ve reached their pinnacle. No breed, to my mind, is more evocative of open ground hunting and trialing stateside than the English Pointer.

The breed standard is a mid-sized dog characterized by athletic grace and power. The dog has a

lean, muscular body, a boxy head, and a barrel chest. The coat is short and dense, liver, orange, lemon, or black, typically in combination with a preponderance of white. The muzzle too is short and square, and there are those who would say that any pointer worthy of the name has a defined split from top lip to nose. Males range in size from 55 to 75 pounds and 25 to 28 inches; females 45 to 65 pounds and 23 to 26 inches. Among Pointer folks, no name is more synonymous with the breed than Elhew, the bloodline perfected by the late Robert Wehle. In the Elhew dogs, the highest representative physicality and temperament of the breed was isolated through the middle part of the 20th Century, and the cream that rose is a line of dogs as field-proven as any the world has seen.

Wehle created his own exacting standards for the dogs that bear his (backwards) name. He sought traits that would prevail in the field, the kennel, and the household, and he made these qualities stick. They are the traits you see in champion English Pointers the world over: regal bearing, high tails, and a sweetness not common in working dogs. But perhaps the most noteworthy trait of the quintessential English Pointer is the electricity, the one that sets them apart.

Many hunters shy away from the breed for fear that they range too far and big for the pocket coverts that abound throughout North America. Indeed, English Pointers from trial stock run big and wide and beautiful, but selective breeding produces close-working strains just as well. Across the board, these dogs are full of energy and focus, and they need the room to exercise it. It would be tempting to make one solely a pet, what for their physical beauty, but that would be robbing the breed of its soul. Whether in the Missouri Breaks or the Maine popple whips, these dogs are built to hunt. They’ll confound you with their raw talent, and make you wish you were as good as they.

As Belle taught me all those years ago, there’s a significance to the English Pointer, something more than the communion of desire and athleticism and beauty. There is a heart, a heart that is wide open and eager to please. Pointers are as guileless as wide-eyed children. But when the kennel door opens, an innate purpose takes over. Pointers will love you, but they will love bird hunting more.

Bruce Mercer of Georgia’s Premier Kennels says it best. “Many of the elite dogs that have been able to rise to the top of the game in the history of the sport are house pets. They understand what you want them to do. They can be mellow in the kennel or in the home, but when it’s time to compete, they are ready to compete. That’s the hereditary and genetic part that kicks in. They have the brains to adapt.”

If only we could all be that good.

First published in Covey Rise