Discovering the Spirit

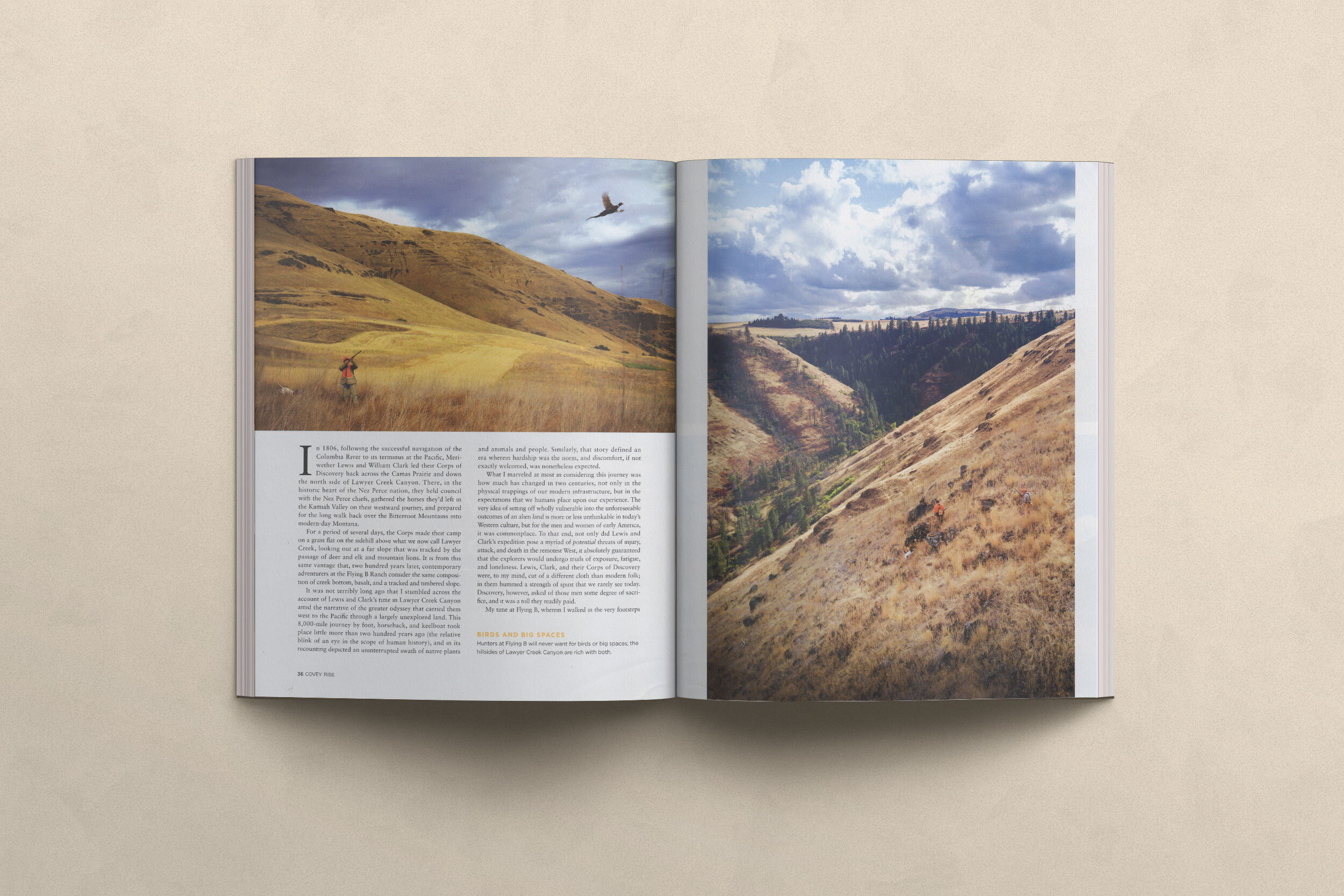

In 1806, following the successful navigation of the Columbia River to its terminus at the Pacific, Meriweather Lewis and William Clark led their Corps of Discovery back across the Camas Prairie and down the north side of Lawyer Creek Canyon. There, in the historic heart of the Nez Perce nation, they held council with the Nez Perce chiefs, gathered the horses they’d left in the Kamiah valley on their westward journey, and prepared for the long walk back over the Bitterroot Mountains into modern-day Montana. For a period of several days, the Corps made their camp on a grass flat on the side-hill above what we now call Lawyer Creek, looking out at a far slope that was tracked by the passage of deer and elk and mountain lion. It is from this same vantage that, two hundred years later, contemporary adventurers at the Flying B Ranch consider the same composition of creek bottom, basalt, and a tracked and timbered slope.

It was not terribly long ago that I stumbled across the account of Lewis and Clark’s time in Lawyer Creek Canyon amidst the narrative of the greater odyssey that carried them west to the Pacific through a largely unexplored land. This 8000-mile journey by foot, horseback, and keelboat took place little more than two hundred years ago (the relative blink of an eye in the scope of human history), and in its recounting depicted an uninterrupted swath of native plants and animals and people. Similarly, that story defined an era wherein hardship was the norm, and discomfort, if not exactly welcomed, was nonetheless expected. What I marveled at most in considering this journey was how much has changed in two centuries, not only in the physical trappings of our modern infrastructure, but in the expectations that we humans place upon our experience. The very idea of setting off wholly vulnerable into the unforeseeable outcomes of an alien land is more-or-less unthinkable in today’s western culture, but for the men and women of early America, it was commonplace. To that end, not only did Lewis and Clark’s expedition pose myriad potential threats of injury, attack, and death in the remotest west, it absolutely guaranteed that the explorers would undergo trials of exposure, fatigue, and loneliness. Lewis, Clark, and their Corps of Discovery were, to my mind, cut of a different cloth than modern folk; in them hummed a strength of spirit that we rarely see today. Discovery, however, asked of those men some degree of sacrifice, and it was a toll they readily paid.

My time at Flying B, wherein I walked in the very footsteps of Lewis and Clark, gave me some food for thought. Over those hillsides I found myself thinking more and more about the rarity of untrammeled landscape, and the rare opportunity to walk in silence and in wilderness, interfacing with a piece of ground in a manner wholly recognizable by the folks who walked it in the centuries before. So too did I find myself ever more aware of the role that strength of spirit and grit plays in the human experience, and how we invariably seek it out in the face of a contemporary world predicated on comfort and abundance. Over the millennia during which Lawyer Creek etched itself into the basalt of the Columbian Plateau, humans across the globe celebrated, integrated, and formalized the opportunity to dig deep and persevere, stitching physical and emotional challenge firmly into the fabric of the broader social culture. Perhaps in light of that history, we humans evolved to rely on such experiences, only to land in a contemporary world that doesn’t necessarily require them, or the lessons they imply. And so it goes that far too often we as a people find ourselves craving something we can’t quite identify in places we don’t quite recognize, and we proceed to either distract ourselves with the comforts of an abundant modern world, or we fabricate experiences that don’t quite scratch the itch we seek to mollify. At root lies the vestige of our own innate need for discovery.

*

A couple years back, on my first trip to Flying B, BJ Walle and I went looking for birds on the side-hills of Lawyer Creek Canyon. It had gotten unseasonably cold overnight, and the ceiling had dropped, carrying a wet and clinging chill to the creek bottom. Well before dawn it started to snow, the sky spitting heavy flakes that clung to the flat places, touching down with a whisper. It all made for a dampening effect, and a silence in the canyon that dulled the swish and gurgle of the creek.

I’d met BJ the evening before in the gun room at the Flying B. He’d come in smiling with a hand extended, an orange tuque perched high on his head. His eyes were bright and intense, and his hands were hard from a life outdoors. “I’ll be hunting you up the canyon tomorrow,” he said. “What are you hoping for?”

At the time I thought this an odd question, in that I’d assumed I’d be at the mercy of his plan, a set program, and the rotation of other hunters. I certainly had no intention of dictating the experience, or a preconceived notion of what the bag might look like. He smiled at my apparent confusion. “What I mean is, how much of an adventure are you looking to have?”

“Well,” I responded, aware of the stirrings in my ego that wished BJ to see me as a pretty rugged fellow, “I’m not afraid to walk, if that’s what you mean.”

“Good,” said BJ. “Where I’m thinking of taking you, we will have plenty of room for that.”

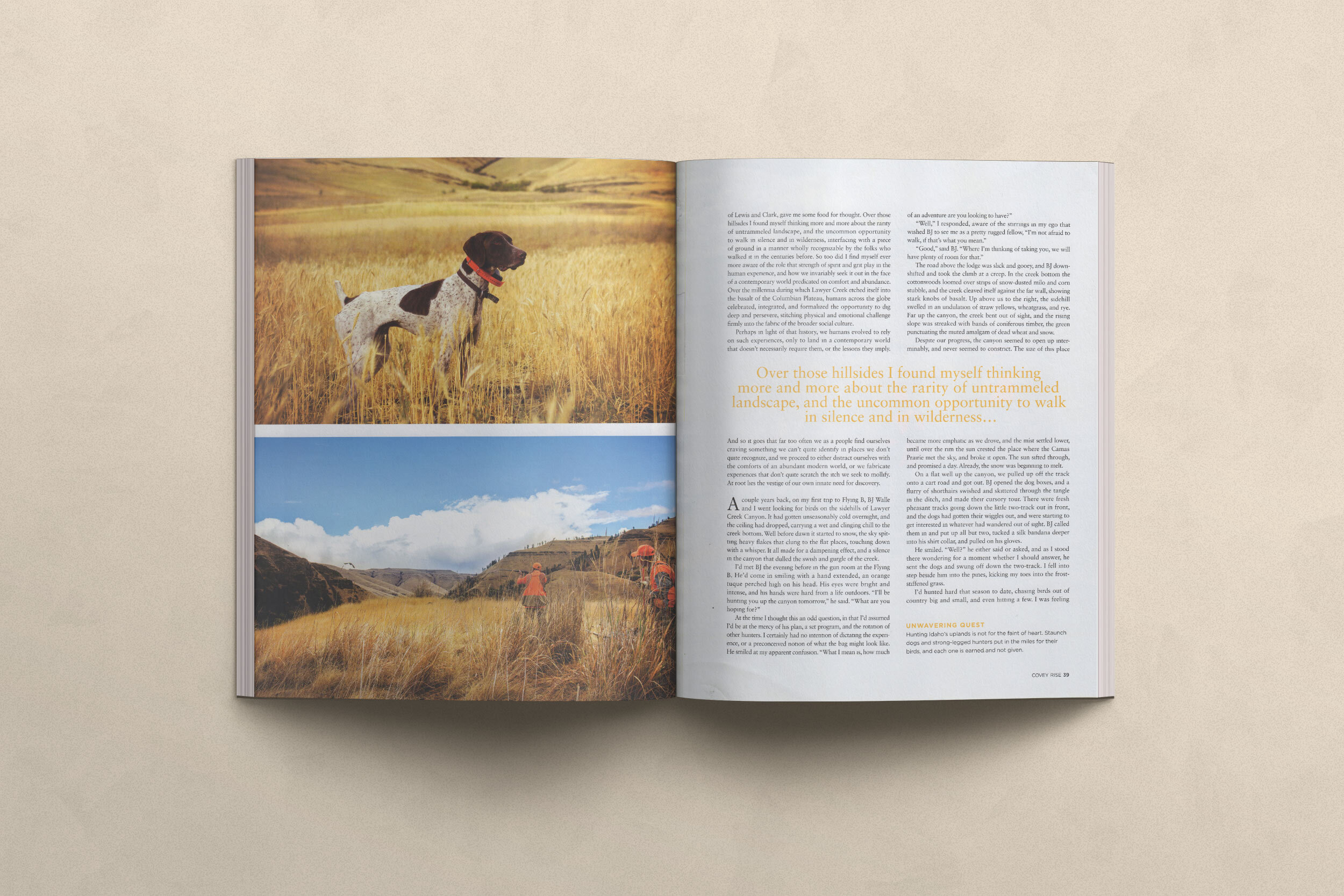

The road above the lodge was a slick and gooey, and BJ down shifted and took the climb at a creep. In the creek bottom the cottonwoods loomed over strips of snow-dusted milo and corn stubble, and the creek cleaved itself against the far wall, showing stark knobs of basalt. Up above us to the right the side-hill swelled in an undulation of straw yellows, wheat grass and rye. Far up the canyon, the creek bent out of sight, and the rising slope was streaked with bands of coniferous timber, the green punctuating the muted amalgam of dead wheat and snow. Despite our progress the canyon seemed to open up interminably, and never seemed to constrict. The size of this place became more emphatic as we drove, and the mist settled lower, until over the rim the sun crested the place where the Camas Prairie met the sky, and broke it open. The sun sifted through, and promised a day. Already, the snow was beginning to melt.

On a flat well up the canyon we pulled up off the track onto a cart road, and got out. BJ opened the dog boxes, and a flurry of shorthairs swished and skittered through the tangle in the ditch, and made their cursory tour. There were fresh pheasant tracks going down the little two-track out in front, and the dogs had gotten their wiggles out, and were starting to get interested in whatever had wandered out of sight. BJ called them in and put up all but two, tucked a silk bandana deeper into his shirt collar, and pulled on his gloves. He smiled. “Well?” he either said or asked, and as I stood there wondering for a moment whether I should answer, he sent the dogs and swung off down the two-track. I fell into step beside him into the pines, kicking my toes into the frost-stiffened grass.

I’d hunted hard that season to date, chasing birds out of country big and small, and even hitting a few. I was feeling strong, feeling that I’d hit a stride of sorts, but this was raw and rough country, and having wandered into it a distance, I suddenly felt very small. In the swell of hill out in front of us there was either opportunity or obligation, but my ego, and a growing awareness that these birds were to be earned and not given, compelled me on. BJ swung the dogs uphill to quarter them out into the grass, and we worked our way steadily along the slick-wet slope after them. A few hundred yards in, the grass got shorter and patchy, and BJ stopped to get his bearings. Up ahead through the burnt wheat tips the stub of a shorthair tail stood tall.

“We got a point…” announced BJ, and smiled, and nodded me along.

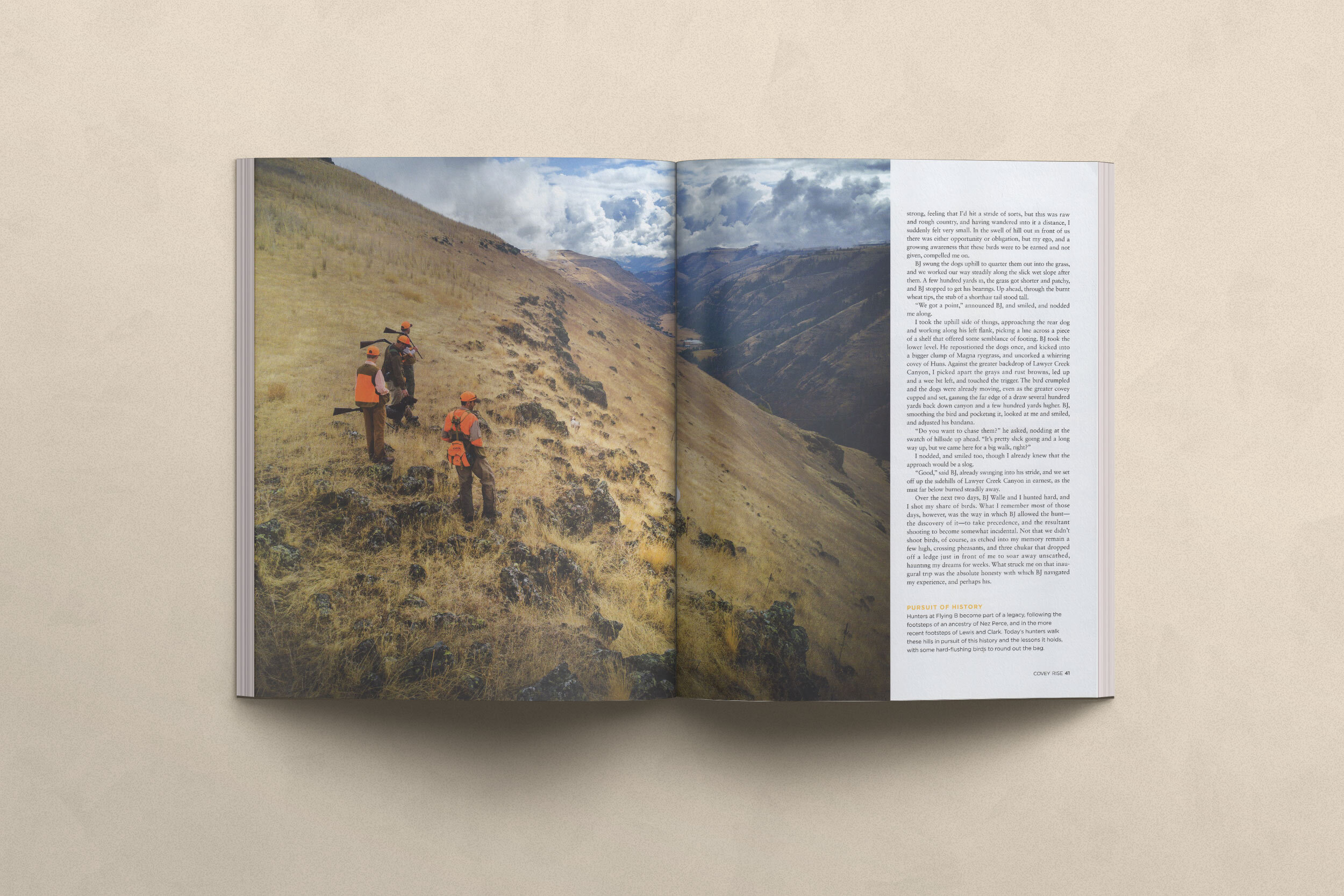

I took the uphill side of things, approaching the rear dog and working along his left flank, picking a line across a piece of a shelf that offered some semblance of footing. BJ took the lower level. He repositioned the dogs once, and kicked into a bigger clump of Magnas ryegrass, and uncorked a whirring covey of huns. Against the greater backdrop of Lawyer Creek Canyon, I picked apart the greys and rust browns, led up and a wee bit left, and touched the trigger. The bird crumpled and the dogs were already moving, even as the greater covey cupped and set, gaining the far edge of a draw several hundred yards back down canyon, and a few hundred yards higher. BJ, smoothing the bird and pocketing it, looked at me and smiled, and adjusted his scarf.

“Do you want to chase them?” he asked, nodding at the swatch of hillside up ahead. “It’s pretty slick going and a long way up, but we came here for a big walk, right?”

I nodded, and smiled too, though I already knew that the approach would be a slog.

“Good,” said BJ, already swinging into his stride, and we set off up the side-hills of Lawyer Creek Canyon in earnest, as the mist far below burned steadily away.

Over the next two days, BJ Walle and I hunted hard, and I shot my share of birds. What I remember most of those days, however, was the way in which BJ allowed the hunt, the discovery of it, to take precedent, and the resultant shooting to become somewhat incidental. Not that we didn’t shoot birds of course, as etched into my memory remain a few high crossing pheasants, and three chukars that dropped off a ledge just in front of me to soar away unscathed, haunting my dreams for weeks. What struck me on that inaugural trip was the absolute honesty with which BJ navigated my experience, and perhaps his.

On the second morning, as I laced my boots on the bumper of his truck, BJ stated his position. “I want you to shoot birds today, but I also want you to learn a little something about yourself. I want you to get up a hill even when you are exhausted, and I want to know that I’ve pushed you to go a little bit longer and farther than you thought you could. This is rough country, and I want you to experience it, and that means being a little bit uncomfortable, and leaving a little bit of yourself in these hills, just enough to know you are getting something from them.” It was a perspective that made the experience all the more resonant for me, and one that compelled me back to Flying B a couple years later, to discover a bit more about the experience to be found there.

*

I returned to Flying B in 2017, having gained a bit more perspective on Lewis and Clark in the time since I’d first visited, and perhaps a bit more perspective on my hunting as well. In my time with BJ, and in the questions that time nurtured about why and how I hunt, I found that my motivations revolve around something far deeper than the bits of flesh and feather I occasionally collect. What I seek in my hunting, and frankly what I don’t always find, is that luminous quality that I believe Lewis and Clark recognized far better. In my hunting I’ve come to celebrate a place of mild discomfort that means I’m working for something, earning something, going just beyond what’s comfortable for the privilege of killing something I cherish. It’s an ethos that has explained to me what it means to be a hunter and a human, and a philosophy that justifies the sore legs and the cold fingertips, and even the little bits of flesh and blood that I donate to the land I intend to take from. There is an equity there, something given for something gained, and just enough required of the human spirit to make it both resonant and worthwhile. This is no doubt a concept that Lewis and Clark and their Corps of Discovery understood, as they leaned into the discomfort and the periodic unknown, full of faith that in the journey there was value.

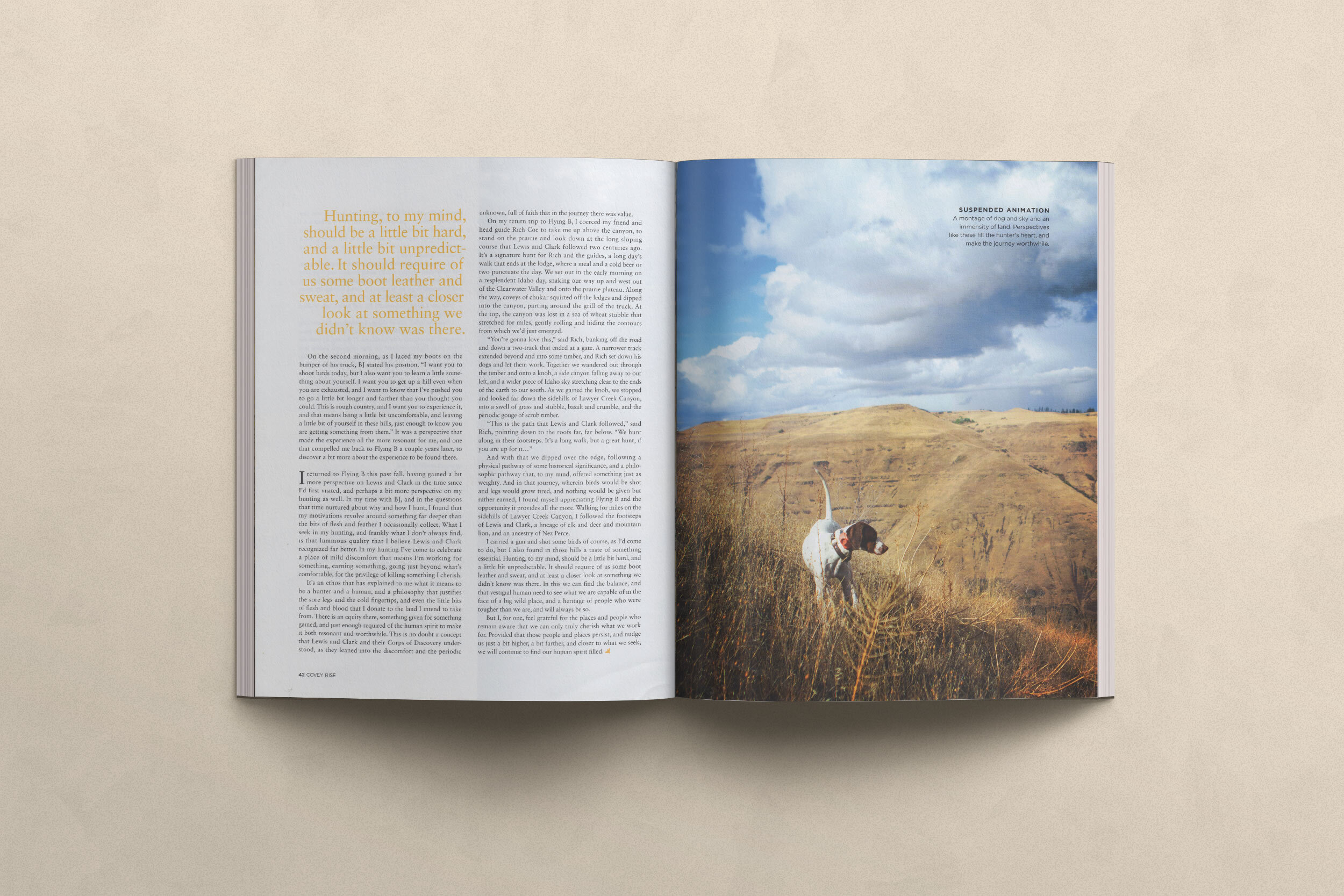

On my return trip to Flying B, I coerced my friend and Head Guide Rich Coe to take me up above the canyon, to stand on the prairie and look down at the long sloping course that Lewis and Clark followed two centuries ago. It’s a signature hunt for Rich and the guides, a long day’s walk that ends at the Lodge, where a meal and a cold beer or two punctuate the day. We set out in the early morning on a resplendent Idaho day, snaking our way up and west out of the Clearwater valley and onto the prairie plateau. Along the way, coveys of chukars squirted off the ledges and dipped into the canyon, parting around the grill of the truck. At the top, the canyon was lost in a sea of wheat stubble that stretched for miles, gently rolling and hiding the contours from which we’d just emerged.

“You’re gonna love this…” said Rich, banking off the road and down a two-track that ended at a gate. A narrower track extended beyond and into some timber, and Rich set down his dogs and let them work. Together we wandered out through the timber and onto a knob, a side canyon falling away to our left, and a wider piece of Idaho sky stretching clear to the ends of the earth to our south. As we gained the knob, we stopped and looked far down the side-hills of Lawyer Creek Canyon, into a swell of grass and stubble, basalt and crumble, and the periodic gouge of scrub timber.

“This is the path that Lewis and Clark followed,” said Rich, pointing down to the roofs far, far below. “We hunt along in their footsteps. It’s a long walk, but a great hunt, if you are up for it…”

And with that we dipped over the edge, following a physical pathway of some historical significance, and a philosophic pathway that, to my mind, offered something just as weighty. And in that journey wherein birds would be shot and legs would grow tired, and nothing would be given but rather earned, I found myself appreciating Flying B and the opportunity it provides all the more. Walking for miles on the side-hills of Lawyer Creek Canyon, I followed the footsteps of Lewis and Clark, a lineage of elk and deer and mountain lion, and an ancestry of Nez Perce. I carried a gun and shot some birds of course, as I’d come to do, but I also found in those hills a taste of something essential. Hunting, to my mind, should be a little bit hard, and a little bit unpredictable. It should require of us some boot leather and sweat, and at least a closer look at something we didn’t know was there. In this we can find the balance, and that vestigial human need to see what we are capable of in the face of a big wild place, and a heritage of people who were tougher than us, and will always be so. But I, for one, feel grateful for the places and people who remain aware that we can only truly cherish what we work for. Provided that those people and places persist, and nudge us just a bit higher, a bit farther, and closer to what we seek, we will continue to find our human spirit filled.

Originally published in Covey Rise June/July 2018