Home on the Range

Given the chance to write about Montana’s PRO Outfitters, I called my friend Simon Perkins.

Simon is the current President of The Orvis Company, an outdoor-industry leader in its third generation of Perkins family ownership. Over the last decade, Simon has come up through the ranks, serving as a merchant, developing hunting products, and overseeing Orvis’ adventure travel arm. Now in his late-30’s and steering, he remains characteristically unimpressed by this ascent. He is a humble guy, but I get the sense that Simon’s reticence stems from a belief that a prior piece of work rings more true.

“I was a fishing guide in Montana for eleven years, and I guided bird hunts for seven…” he’ll occasionally say with a sort of pride we should probably all reserve for our craft.

Simon spent his formative years schlepping gear for fishing clients, following dogs over the prairie, back-rowing rivers on PRO’s behalf. Before leaving Montana and returning to the Vermont of his childhood, he cut his teeth on the management of PRO Outfitter’s digital marketing. I told him that I was writing a story, that though I had my own experiences to draw upon, I needed some perspective on what makes PRO Outfitters, notably the hunting experience out of the company’s Sharptail Lodge, so unique.

He chewed on the question for a little while before asking “so, you’re trying to explain what is special about PRO? And you’re trying to capture it in one article?”

I confirmed.

Simon was quiet. I sat, pencil on paper, ready to scribble down the little chestnut he was no doubt about to hand over. This was going to be easy.

“Well,” said Simon Perkins, a guy who doesn’t see obstacles, but only opportunities, “sorry… you are gonna have a lot of trouble with this one.”

Needless to say, I was a little off-put, rattled by my friend’s lack of confidence.

“No, no…” he responded when I pressed. “It has nothing to do with you. The problem is PRO. It’s just too nuanced. There are too many layers of place and people and history that make it special. PRO has a certain magic that has nothing to do, and everything to do, with birds and trout. It’s magic you won’t be able to put into words; it doesn’t play well to a definition.”

Simon does this. He sees the complexities at once, the bits that you aren’t quite seeing. Fortunately, he is generous enough to grab your hand, and to pilot you into the weeds beside him to take a closer look. Case in point:

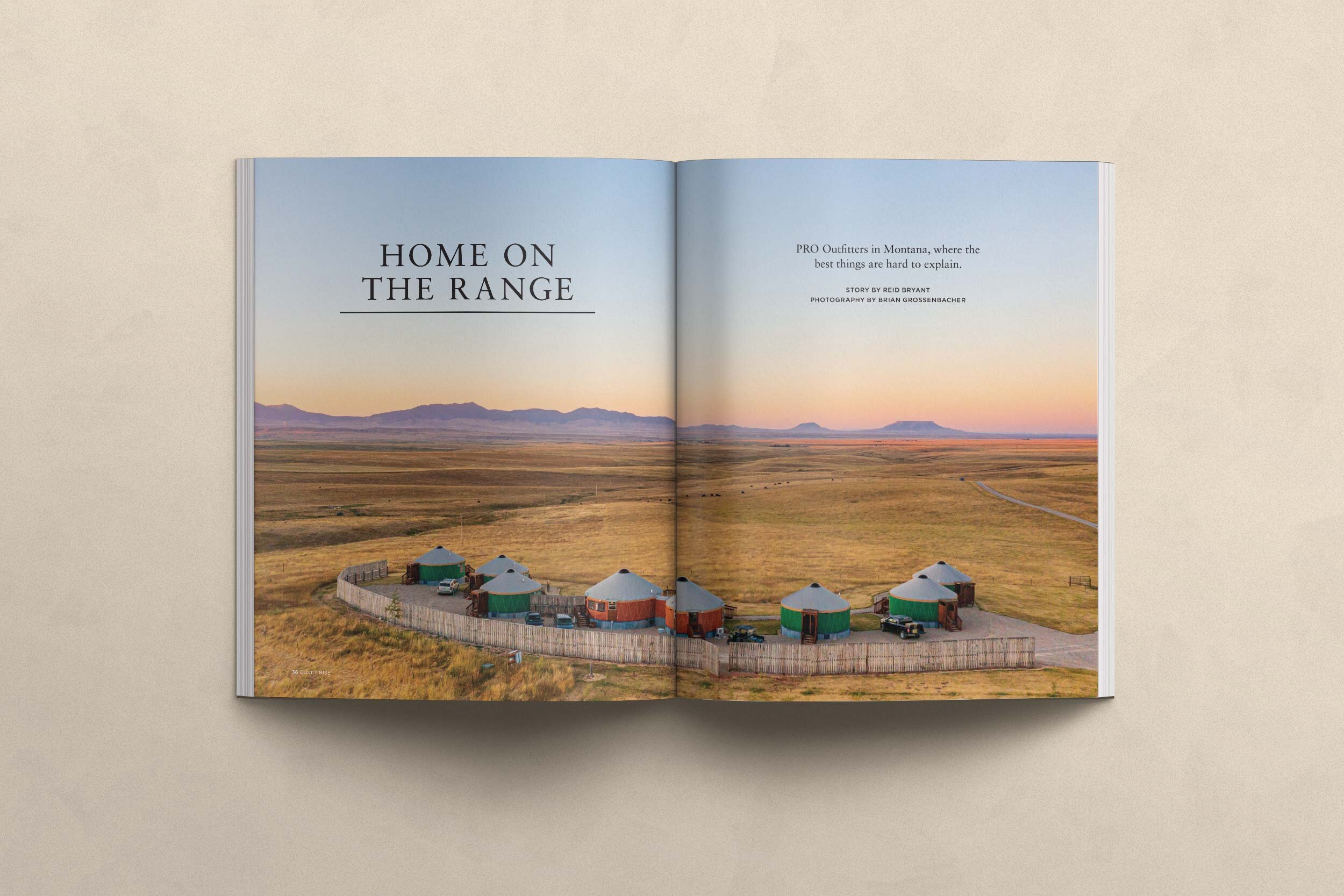

“Think about it this way: you have an outfitting business started almost fifty years ago by Paul Roos and Johnny Kowalski, two small-town Montana guys who became legends in Montana outfitting circles. You have a hunting culture in which killing birds is secondary to watching bird-dogs, where each dog is celebrated for its hero moments and its epic fails, cherished equally for both. In the Sharptail you have cluster of yurts nestled smack in the middle of what may be the finest piece of prairie bird habitat in the lower 48. You have 200,000 acres of access, ground stitched together through handshake deals and a look in the eye. You have relationships between guides and guests and ranchers that have evolved over decades and generations, the viability of which hinges on mutual respect and trust. You have a business that functions like a family, with all the love and occasional friction that a family brings to bear. You have the simple fact that PRO only hunts wild birds, that the hunt unfolds without any sort of guarantee, entirely without artifice, and a ‘NO-NO’ (i.e. no birds taken) elicits horn-blowing and cheers back at the Lodge, playful recognition that in wild bird hunting you are up against something that is designed to be better than you. You take all of that, you bundle it all up, and you give it to people, hoping that they see the same magic in it that you do. If they want in, you make it part of their story too.”

Simon assembled his thoughts like scattered papers, stacked them in a pile, “there are plenty of experiences that have adventure on the surface, that have dogs running around and birds getting shot, great meals and fun people in beautiful settings. But when you become part of something that is given the freedom to be its unadulterated, honest best, it tugs at you, at your head and your heart. You can’t explain how or why; it creates its own mythology.”

I absorbed all this as best I could, growing increasingly convinced that Simon was right; I was in for some heavy sledding. I watched that sour mixture of dread and panic spiraling toward the drain of an impending deadline. And as I so often do, I asked Simon to help me. He left me with this:

“Look; when I was guiding out there, my English setter Maeby had a littermate named Tito. Maeby picked up the game quickly from the other dogs—finding birds, honoring. But Tito… Tito took a little longer to get it. Any other outfit would have written him off, sold him as a pet, made a house dog out of him. But as is their way, the guides at PRO let him learn at his own pace, kept giving him shots, kept the faith in him. It took some time, but when he got to be three or four, Tito was a stud, a total rock star. We called him our #1 Starter. All it took was the willingness to let things happen in their natural course, and the curiosity to see what that dog might become… and, I guess, about three years. That’s a good illustration of PRO. There’s a lot of faith in the fact that special things are all around, just waiting to prove themselves, but not always in obvious ways.”

With that, I guess I got my chestnut after all.

Simon went back to being a hunting guide first and a business guy second, and I went back to chewing on my pencil. I’ve been chewing for days now, starting and restarting this piece. I keep coming back to the stories that Simon mentioned… the little vignettes, the slivers of lore, the tender exchanges between dogs and guides, the characters. Beneath these stories, I hope to do justice to an experience that is broader than any guided day on the prairie, richer than any popcorn flush, more lovely than even the staunchest point. PRO Outfitters is a symphony of all those things, and so, so many more. And like a symphony, it evolves with each performance.

*

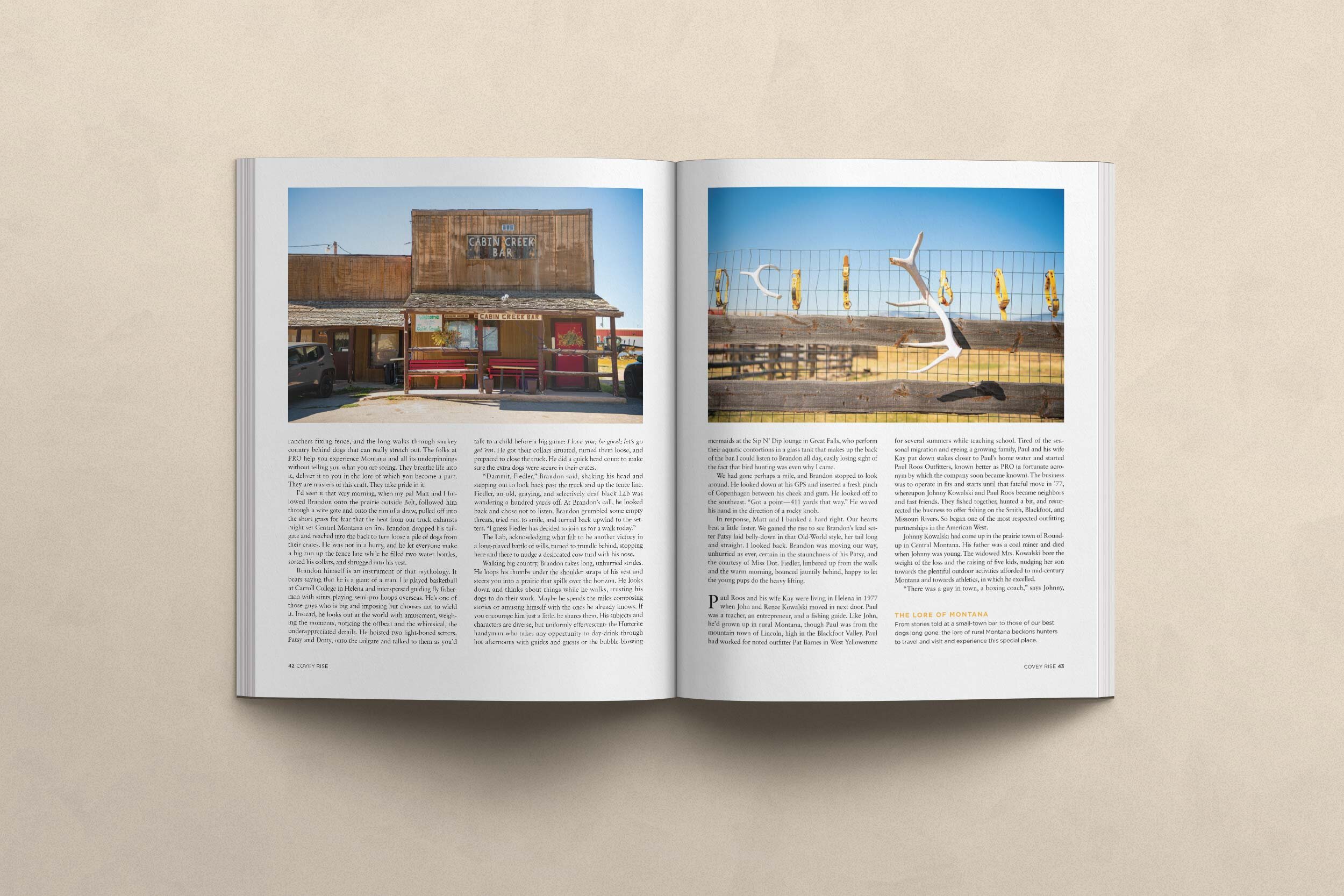

On a winter night some years ago, a half-dozen Montana ranchers sat drinking at the Cabin Creek Bar. They’d come in out of the early nighttime, leaving heelers to sit watch in the cabs of flatbed pickups. There was weather rolling in. The men looked out from under their hat brims and past their beers into the mirror that filled the wall behind the liquor bottles. Speaking to their own reflections, they opined that Judith Basin was in for some snow, and at the rate things were going, an April thaw was a long way off.

The story goes that the advancing storm came up the slot between the Highwoods and the Little Belts, icy wind with a blizzard chaser. It tumbled into Geyser in a whine, whistled between the legs of the water tower. Exposed as it was, the town bent before the weather. One gust cut across the power poles on Main Street, and the lights of town collectively flickered and died.

It’s unclear what transpired next. What we do know is that some seconds later, Geyser’s circuitry re-connected itself, breakers were flipped, and the lights of the little town buzzed back on. In the sputtering overheads of the Cabin Creek Bar, one rancher lay slumped in his seat, a pool of blood soaking the napkin upon which he’d placed his Coors bottle. His throat had been slit ear-to-ear.

On a day in mid-September, Brandon Boedecker, owner of PRO Outfitters, stepped up onto the porch of the Cabin Creek Bar, pulled open the door, and moved aside to let me through. A triangle of light cut into shadows, illuminating motes of prairie dust that sparkled like gold. “They never solved the crime…” he allowed, taking off his sunglasses and propping them on the bill of his hat. He seemed amused at the irony, and at my newfound hesitation to join him in this place for an afternoon beer. “I bet I could have solved it in about thirty seconds…” He followed me in, nodded approvingly at the football game on the TV, and took a seat at one end of the bar. The wedge of sunlight on the dusty floor grew smaller and more acute as the door swung closed, silencing the warm wind of a September afternoon.

I have no idea whether the story Brandon told is true or not. I guess I’ve come to think it good to sometimes look beyond the relevance of facts, to focus instead on what Joseph Campbell might have called The Power of Myth.

What I do know is this: Brandon Boedecker landed his story. He let it unfold on the sidewalk of a tiny, hardscrabble town in Central Montana, a place as lean and rawhide tough as the cattlemen and sheepherders who built it. He floated it out with signature nonchalance, as if such things were commonplace, let me suck it down with all the innocence of a cutthroat trout. He wove in just enough of the matter-of-fact, and he left out just enough of the pertinent detail. Then he bought me a beer.

I’d assume that despite his investment in the football game, he saw me inspecting the wood beneath my bottle.

I’ve come to think that all of this is a central piece of the PRO mythology. Maybe its performance art, though calling it that threatens to cheapen it. It’s got a bit more starch than that, what with the reality of the small-town cafes, the hard-handed ranchers fixing fence, the long walks through snakey country behind dogs that can really stretch out. The folks at PRO help you experience that Montana and all its underpinnings without telling you what you are seeing. They breathe life into, deliver it to you in the lore of which you become a part. They are masters of this craft; they take pride in it.

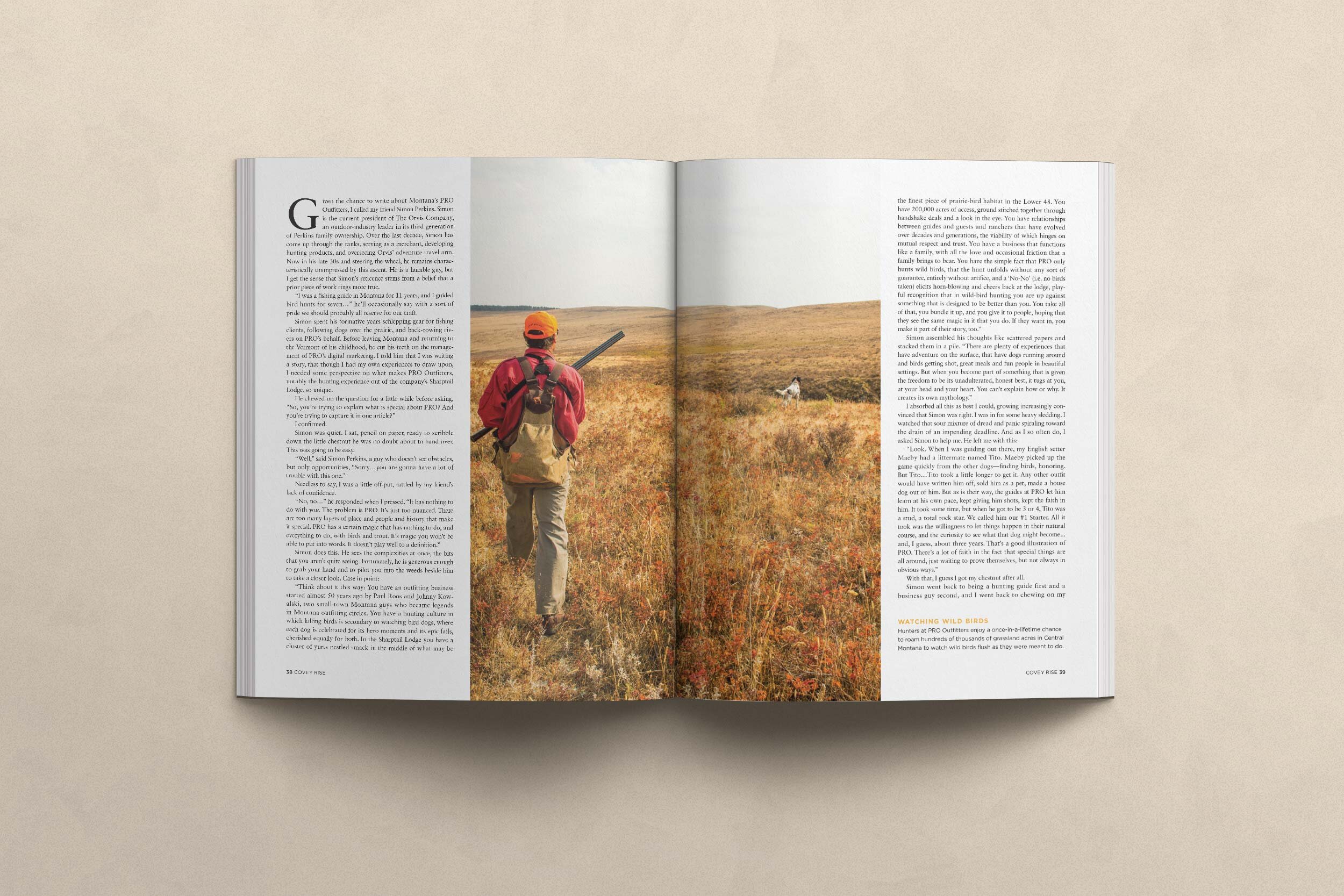

I’d seen it that very morning, when my pal Matt and I followed Brandon onto the prairie outside Belt, followed him through a wire gate and onto the rim of a draw, pulled off into the short grass for fear that the heat from our truck exhausts might set central Montana on fire. Brandon dropped his tailgate and reached into the back to turn loose a pile of dogs from their crates. He was not in a hurry, and he let everyone make a big run up the fence line while he filled two water bottles, sorted his collars, and shrugged into his vest.

Brandon himself is an instrument of that mythology. It bears saying that he is a giant of a man. He played basketball at Carroll College in Helena, and interspersed guiding fly fishermen with stints playing semi-pro hoops overseas. He’s one of those guys who is big and imposing but chooses not to wield it; instead, he looks out at the world with amusement, weighing the moments, noticing the offbeat and the whimsical, the under-appreciated details. He hoisted two light-boned setters, Patsy and Dotty, onto the tailgate and talked to them as you’d talk to a child before a big game: I love you; be good; let’s go get ‘em. He got their collars situated, turned them loose, and prepared to close the truck. He did a quick head count to make sure the extra dogs were secure in their crates.

“Dammit, Fiedler…” Brandon said, shaking his head and stepping out to look back past the truck and up the fence line. Fiedler, an old, graying, and selectively deaf black lab was wandering a hundred yards off. At Brandon’s call, he looked back and chose not to listen. Brandon grumbled some empty threats, tried not to smile, and turned back upwind to the setters. “I guess Fiedler has decided to join us for a walk today.”

The lab, acknowledging what felt to be another victory in a long-played battle of wills, turned to trundle behind, stopping here and there to nudge a desiccated cow turd with his nose.

Walking big country, Brandon takes long, unhurried strides. He loops his thumbs under the shoulder straps of his vest and steers you into a prairie that spills over the horizon. He looks down and thinks about things while he walks, trusting his dogs to do their work. Maybe he spends the miles composing stories, or amusing himself with the ones he already knows. If you encourage him just a little, he shares them. His subjects and characters are diverse, but uniformly effervescent: the Hutterite handyman who takes any opportunity to day-drink through hot afternoons with guides and guests; the bubble-blowing mermaids at the Sip N’ Dip lounge in Great Falls, who perform their aquatic contortions in a glass tank that makes up the back of the bar; the saga of an interrupted hunting-day tryst between a noted outdoor writer and his publisher… in a plum thicket. I could listen to Brandon all day, easily losing sight of the fact that bird hunting was even why I came.

We had gone perhaps a mile, and Brandon stopped to look around. He looked down at his GPS and inserted a fresh pinch of Copenhagen between his cheek and gum. He looked off to the southeast. “Got a point; four-hundred-and-eleven yards that way.” He waved his hand in the direction of a rocky knob.

In response, Matt and I banked a hard right. Our hearts beat a little faster. We gained the rise to see Brandon’s lead setter Patsy laid belly-down in that old-world style, her tail long and straight. I looked back. Brandon was moving our way, unhurried as ever, certain in the staunchness of his Patsy, and the courtesy of Miss Dot. Fiedler, limbered up from the walk and the warm morning, bounced jauntily behind, happy to let the young folks do the heavy lifting.

*

Paul Roos and his wife Kay were living in Helena in 1977 when John and Renee Kowalski moved in next door. Paul was a teacher, an entrepreneur, and a fishing guide; like John he’d grown up in rural Montana, though Paul was from the mountain town of Lincoln high in the Blackfoot Valley. Paul had worked for noted outfitter Pat Barnes in West Yellowstone for several summers while teaching school. Tired of the seasonal migration, and eyeing a growing family, Paul and his wife Kay put down stakes closer to Paul’s home water and started Paul Roos Outfitters, known better as PRO (a fortunate acronym by which the company soon became known). The business was to operate in fits and starts until that fateful move in ’77, whereupon Johnny Kowalski and Paul Roos became neighbors and fast friends. They fished together, hunted a bit, and resurrected the business to offer fishing on the Smith, Blackfoot, and Missouri Rivers. So began one of the most respected Outfitting partnerships in the American West.

Johnny Kowalski had come up on in the prairie town of Roundup in central Montana. His father was a coal miner and died when Johnny was young. The widowed Mrs. Kowalski bore the weight of the loss and the raising of five kids, nudging her son toward the plentiful outdoor activities afforded to mid-century Montana, and towards athletics, in which he excelled.

“There was a guy in town, a boxing coach,” says Johnny, describing the Montana of his youth. “He used to take us around to all the other small towns for matches. It was a big deal; all the people in town would turn out to watch… ranchers and cowboys too. There wasn’t much else going on back then.”

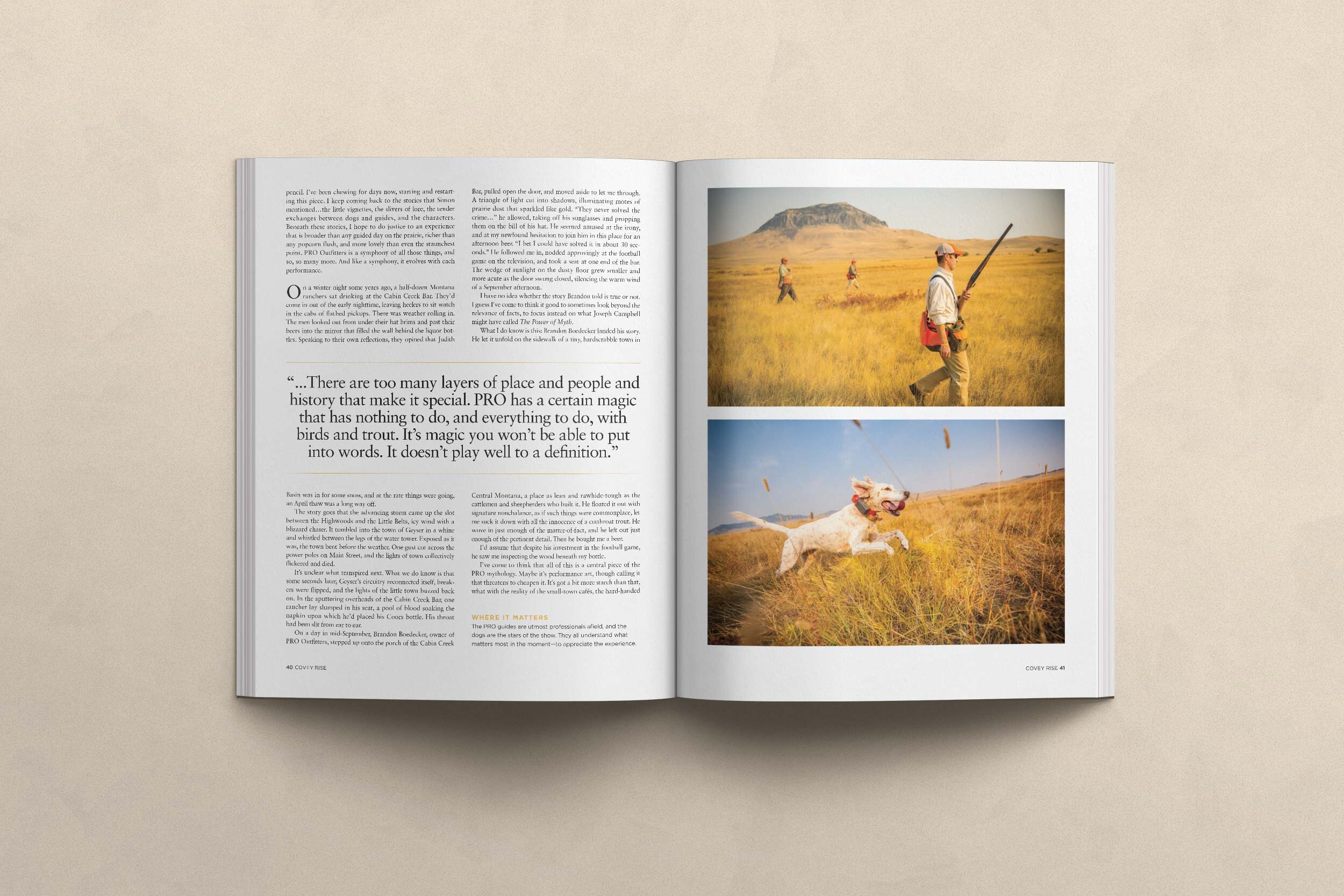

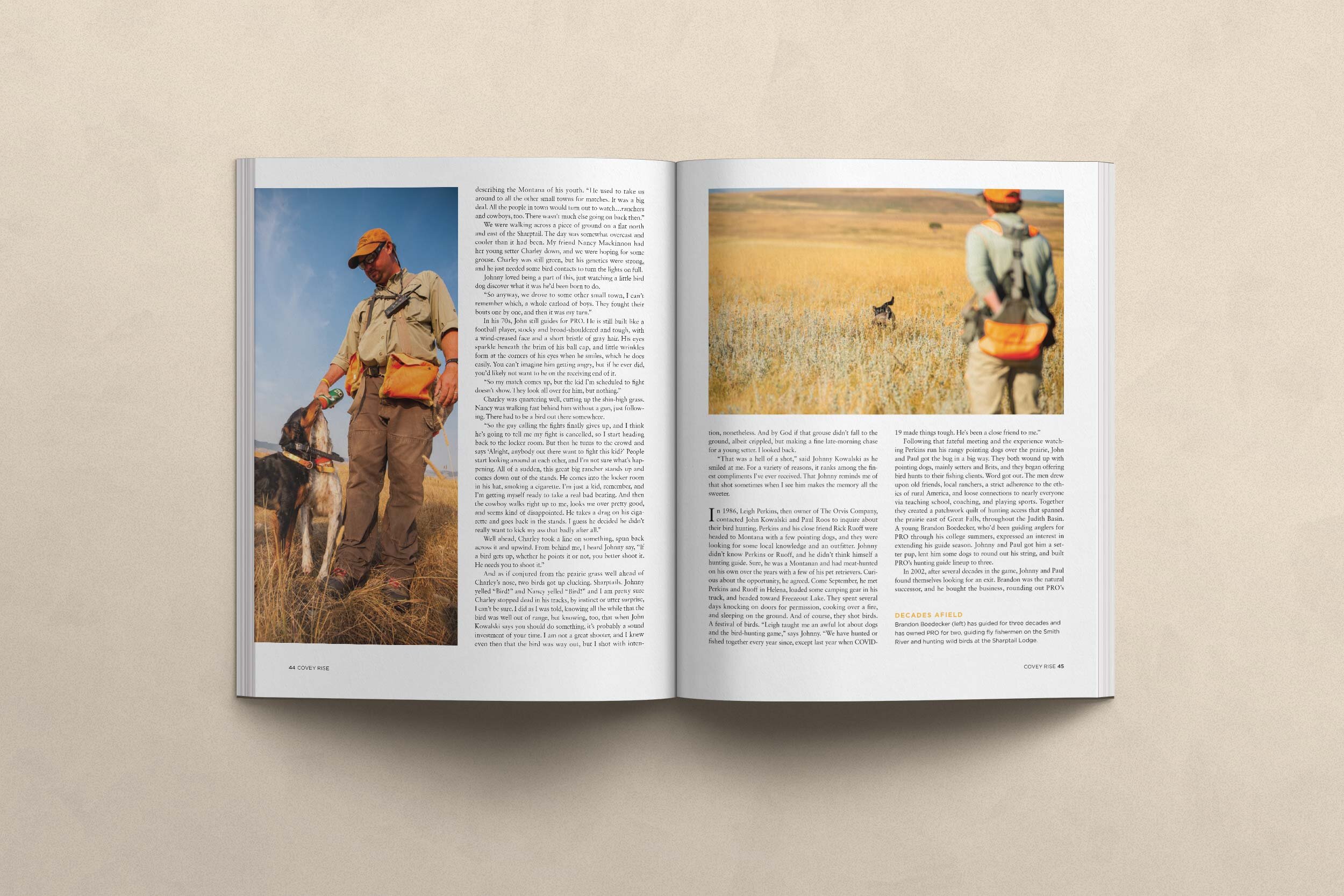

We were walking across a piece of ground on a flat north and east of the Sharptail. The day was somewhat overcast and cooler than it had been. My friend Nancy Mackinnon had her young setter Charley down, and we were hoping for some grouse. Charley was still green, but his genetics were strong, and he just needed some bird contacts to turn the lights on full.

Johnny loved being a part of this, just watching a little bird dog discover what it was he’d been born to do.

“So anyway, we drove to some other small town, I can’t remember which, a whole carload of boys. They fought their bouts one by one, and then it’s my turn.”

In his 70’s, John still guides for PRO. He is still built like a football player, stocky and broad-shouldered and tough, with a wind-creased face and a short bristle of gray hair. His eyes sparkle beneath the brim of his ball cap, and little wrinkles form at the corners of his eyes when he smiles, which he does easily. You can’t imagine him getting angry, but if he ever did, you’d likely not want to be on the receiving end of it.

“So my match comes up, but the kid I’m scheduled to fight doesn’t show. They look all over for him, but nothing.”

Charley was quartering well, cutting up the shin-high grass. Nancy was walking fast behind him without a gun, just following. There had to be a bird out there somewhere.

“So the guy calling the fights finally gives up, and I think he’s going to tell me my fight is cancelled, so I start heading back to the locker room. But then he turns to the crowd and says ‘Alright, anybody out there want to fight this kid?’ People start looking around at each other, and I’m not sure what’s happening, and all of a sudden, this great big rancher stands up and comes down out of the stands. He comes into the locker room in his hat, smoking a cigarette. I’m just a kid, remember, and I’m getting myself ready to take a real bad beating. And then the cowboy walks right up to me, looks me over pretty good, and seems kind of disappointed. He takes a drag on his cigarette and goes back in the stands. I guess he decided he didn’t really want to kick my ass that badly after all…”

Well ahead, Charley took a line on something, spun back across it and upwind. From behind me, I heard Johnny say, “if a bird gets up, whether he points it or not, you better shoot it. He needs you to shoot it.”

And as if conjured from the prairie grass well ahead of Charley’s nose, two birds got up clucking. Sharptails. Johnny yelled “Bird!” and Nancy yelled “Bird!” and I am pretty sure Charley stopped dead in his tracks, by instinct or utter surprise I can’t be sure. I did as I was told, knowing all the while that the bird was well out of range, but knowing too that when John Kowalski says you should do something, it’s probably a sound investment of your time. I am not a great shooter, and I knew even then that the bird was way out, but I shot with intention, nonetheless. And by God if that grouse didn’t fall to the ground, albeit crippled, but making a fine late-morning chase for a young setter. I looked back.

“That was a hell of a shot,” said Johnny Kowalski, and smiled at me. For a variety of reasons, it ranks among the finest compliments I’ve ever received. That Johnny reminds me of that shot sometimes when I see him makes the memory all the sweeter.

*

In 1986, Leigh Perkins, then owner of The Orvis Company, contacted John Kowalski and Paul Roos to inquire about their bird hunting. Perkins and his close friend Rick Ruoff were headed to Montana with a few pointing dogs, and they were looking for some local knowledge, and an outfitter. Johnny didn’t know Perkins or Ruoff, and he didn’t think himself a hunting guide. Sure, he was a Montanan, and had meat-hunted on his own over the years with a few of his pet retrievers. Curious about the opportunity, he agreed. Come September, he met Perkins and Ruoff in Helena, loaded some camping gear in his truck, and headed toward Freezeout Lake. They spent several days knocking on doors for permission, cooking over a fire, and sleeping on the ground. And of course, they shot birds. A festival of birds. “Leigh taught me an awful lot about dogs and the bird hunting game,” says Johnny. “We have hunted or fished together every year since, except last year, when COVID made things tough. He’s been a close friend to me.”

Following that fateful meeting, and the experience watching Perkins run his rangy pointing dogs over the prairie, John and Paul got the bug in a big way. Both Johnny and Paul wound up with pointing dogs, mainly setters and Brits, and they began offering bird hunts to their fishing clients. Word got out. The men drew upon old friends, local ranchers, a strict adherence to the ethics of rural America, and loose connections to nearly everyone via teaching school, coaching, and playing sports. Together they created a patchwork quilt of hunting access that spanned the prairie east of Great Falls, throughout the Judith Basin. A young Brandon Boedecker, who’d been guiding anglers for PRO through his college summers, expressed an interest in extending his guide season. Johnny and Paul got him a setter pup, lent him some dogs to round out his string, and built PRO’s hunting guide lineup to three.

In 2002, after several decades in the game, Johnny and Paul found themselves looking for an exit. Brandon was the natural successor, and he bought the business, rounding out PRO’s assortment of wilderness float trips on the Smith River, a fishing lodge at North Fork Crossing on the Blackfoot, and day trips on the Missouri in Craig with the purchase of a small property east of Great Falls. This would become the Sharptail Lodge.

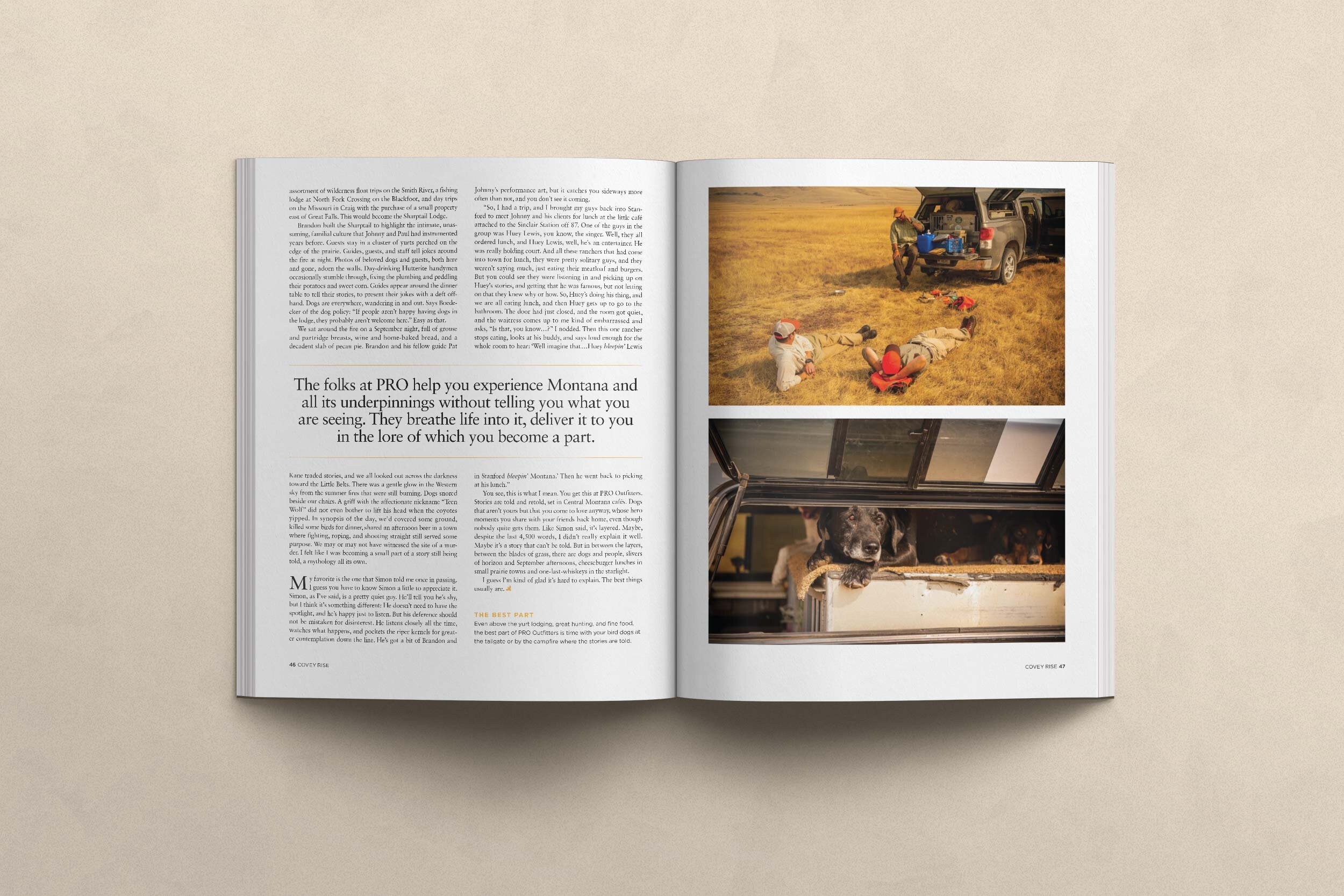

Brandon built the Sharptail to highlight the intimate, unassuming, familial culture that Kowalski and Roos had instrumented years before. Guests stay in a cluster of yurts perched on the edge of the prairie. Guides, guests, and staff tell jokes around the fire at night, and compete in such fanciful events as the “Mother Shucker” (which necessitates an overnight oyster delivery via fedex), and the “Blue Grouse Open”, a competition among guides to see who, in a single season, can bring home the greatest number of reverse-migrating Blues (the winner gets his or her name inscribed on a plaque). Photos of beloved dogs and guests, both here and gone, adorn the walls. Day-drinking Hutterite handymen occasionally stumble through, fixing the plumbing and peddling their potatoes and sweet corn. Guides appear around the dinner table to tell their stories, to present their jokes with a deft offhand. Dogs are everywhere; they wander in and out. Says Boedecker of the dog policy: “If people aren’t happy having dogs in the lodge, they probably aren’t welcome here.” Easy as that.

We sat around the fire on a September night, full of grouse and partridge breasts, wine and home-baked bread, a decadent slab of pecan pie. Brandon and his fellow guide Pat Kane traded stories, my pal Matt giggled, and we all looked out across the darkness toward the Little Belts. There was a gentle glow in the western sky from the summer fires that were still burning. Dogs snored beside our chairs. A Griff with the affectionate nickname “Teen Wolf” did not even bother to lift his head when the coyotes yipped. In synopsis of the day, we’d covered some ground, killed some birds for dinner, shared an afternoon beer in a town where fighting, roping, and shooting straight still served some purpose. We may or may not have witnessed the site of a murder. I felt like I was becoming a small part of a story still being told, a mythology all its own.

*

My favorite is the one that Simon told me once in passing. I guess you have to know Simon a little to appreciate it.

Simon, as I’ve said, is a pretty quiet guy. He’ll tell you he’s shy, but I think it’s something different: he doesn’t need to have the spotlight, and he’s happy just to listen. But his deference should not be mistaken for disinterest; Simon listens closely all the time, watches what happens, and pockets the riper kernels for greater contemplation down the line. He’s got a bit of Brandon and Johnny’s performance art, but it catches you sideways more often than not, and you don’t see it coming.

“So, I had a trip, and I brought my guys back into Stanford to meet Johnny and his clients for lunch at the little café attached to the Sinclair station off 87. One of the guys in the group was Huey Lewis, you know, the singer. Well, they all ordered lunch, and Huey Lewis, well, he’s an entertainer. He was really holding court. And all these ranchers that had come into town for lunch, they were pretty solitary guys, and they weren’t saying much, just eating their meatloaf and burgers. But you could see they were listening in and picking up on Huey’s stories, and getting that he was famous, but not letting on that they knew why or how. So, Huey’s doing his thing, and we are all eating lunch, and then Huey gets up to go to the bathroom. The door had just closed, and the room got quiet, and the waitress comes up to me kind of embarrassed and asks, “Is that, you know…”. I nodded. Then this one rancher stops eating, looks at his buddy, and says loud enough for the whole room to hear: “Well imagine that… Huey fuckin’ Lewis in Stanford fuckin’ Montana.” Then he went back to picking at his lunch.”

You see, this is what I mean. You get this at PRO Outfitters. Stories told and retold, set in central Montana cafes. Dogs that aren’t yours but that you come to love anyway, whose hero moments you share with your friends back home, even though nobody quite gets them. Like Simon said, it’s layered. Maybe, despite the last 4500 words, I didn’t really explain it well. Maybe it’s a story that can’t be told. But in between the layers, between the blades of grass, there are dogs and people, slivers of horizon and September afternoons, cheeseburger lunches in small prairie towns and one-last-whiskeys in the starlight.

I guess I’m kind of glad it’s hard to explain. The best things usually are.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine