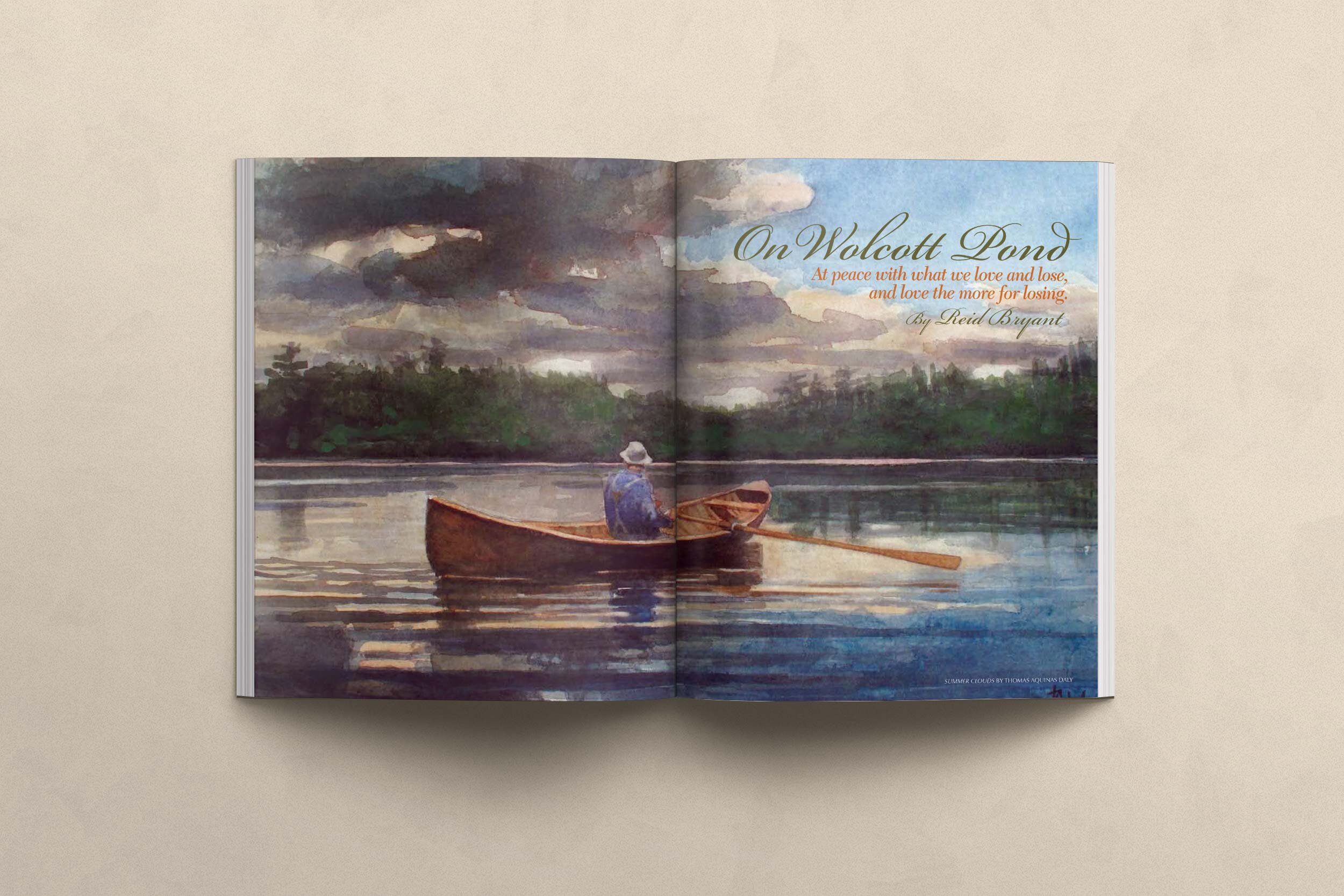

On Wolcott Pond

Looking back on it, I can barely remember the contours of Wolcott Pond, and sadly, these fifteen years later I might not even be able to find the place. But the feeling always comes to me strong this time of year, as the sun takes a shallower path across the late summer sky. It’s an odd and slightly disconcerting thing to remember a place in the gut, and to realize that the details of it have been lost beneath the detritus of age and amassed memory. But the feeling returns, and the image of one magnificent fish and sunlight sifted through fir boughs, and the certainty that something was soon to be lost.

I was house-sitting at Ann and Dave’s that summer, as they had taken North on another of their long journeys into Labrador. Much to my surprise, they’d asked me to watch over the place: the garden, the house, the wood-fired cook stove, and Tobey the aging Brittany. Even I was skeptical of my ability to keep house, just an 18-year-old kid after all, and none too responsible by any account. As they pulled west and north onto the dirt road and honked a goodbye, Tobey raised his head and followed the dust and the engine noise. He whined once and looked at me and rested his head on his outstretched legs once again, closing his eyes with a sigh. Soon all sound of the car disappeared, leaving only the chirr of crickets and a breeze in the grass of the sheep pasture. Somehow, though, under the silence, the end of a season was clattering to the ground all around us. I sat down and closed my eyes. With a hand on Tobey’s knobby head, I leaned back against a fence rail to pretend that this was in fact my life. As I did so, it all seemed so unreal.

*

Vermont seasons probe the boundaries of possibility, much in the way the Green Mountains push at the northern borders of our country, creeping over just a little into Canada. A summer in the Northeast Kingdom is condensed into a wildly succulent couple of months, when all living things fill to bursting on the lushness of the season. Love is made, offspring cast upon the wind or settled firmly in the belly, and then it’s over. Something shifts in August, foretelling the wood smoke and frost, a jubilation of radiant color, then the clamp of winter that falls over the hills. Summer is but a pair of glowing months, and I sat there drinking in the end of it, noting the metallic sadness that hinted at the coming fall.

I’d fallen in love the previous year, with a girl I’d no more understood than deserved. She was, in fact, as lovely and fleeting as anything I’d yet known, with hair the color of oat-straw and a childlike, pigeon-toed gait. She was strong and blue-eyed, and her name was Jackie. She came from a poor and proud and splintered family. Maybe it was this that I loved most, her willingness to look straight at the collapse of her people and still see beauty in the world, to seek it in fact, in the simple designs all about us. We walked together over the dirt roads of the town where we’d met, and we rejoiced in the grit of the winter. She wrapped me in a blanket beside her on a north-facing hillside above Wolcott Pond one night, and introduced me to the Aurora Borealis. There, dancing somewhere over the water, reds and greens and honey-golds streaked down towards us, creating a light that cast its own shadows on the darkness behind it. It was all so magical and so mysterious that it scared me a little, as I could no more make sense of this cataract of color than I could understand the lovely girl whose hands were wrapped in mine. All I knew was that both were beautiful, and that neither were quite what they seemed.

I opened my eyes when the sun-shadow dropped behind the trees, and it was cooler. I was hungry, and Tobey and I walked up through the sheep pasture and back towards the door. We went inside and Tobey ran right for his bowl and scratched the slate floor. A loaf of coarse bread lay on the table, and I broke off an end for him. I chucked it in his bowl and he inhaled it, seeming happier, and licked around the edges of his bowl for crumbs that were not there. I got a beer from the fridge and walked to the phone, that I might call Jackie to tell her Anne and Dave were gone, and she should come down from her room on the Common.

*

We ran Tobey beside Wolcott Pond that evening, beneath a crisping twilight. The dry-dustiness had left the air, edged out by a heavier chill, and the space all around us was sharpened. Bats and nighthawks swooped, circled, became a kaleidoscope of motion upon the purpling sky. Tobey drifted among the firs chasing intangibles, and re-emerged only to pounce on the same amidst the wet hummocks of the pond edge. His purpose, real or imagined, was more frivolous than mine. I walked beside Jackie near enough to feel the warmth of her, the closeness anyway. She never reached to take my hand, and I dared not force hers. I pointed out the places where the big bass lay, hoping words would fill the gulf, and swept an arm over the pasture, wondering aloud where all the July fireflies had gotten to. Jackie shrugged, pulling her steps from the squelching mud. The space between us undermined our proximity, and it hung there, an unseen but stratifying presence. I reached out to her once, and touched her hand as she pushed a strand of hair behind her ear. She stopped walking and looked at me, but somehow not with reassurance. She looked at me as if from a distance, as if scanning a valley below her in which I felt myself wandering, wondering, looking for something that was just out of reach. I took my hand away.

A bullfrog grumped from the muddy edges, and I turned toward it. The night was coming quicker now, and engulfing the day in that luminous glow of a moon just rising, and a sun just set. I scanned the shallows for the frog, looking hard for something real on which to focus while fear and distance eddied in my heart. The water had achieved that cellophane skin. It grabbed the sky and threw it back, and undulated with the goings-on of shallow water. Panfish smacked the lilies. The bullfrog shut up. A big bass swirled hard out by the deadheads, and arrested me for a second, setting me free from my thoughts. That reflexive excitement filled the frame enough to make my heart beat hard, but receded with the ripples, till the fear and distance were centered again, and a wet dog slipped past my leg. I looked over at Jackie. She too was looking out over the water.

“We should get Tobey home before we lose him. You can stay with me at Ann and Dave’s if you like.” I hoped she’d look at me, but she didn’t. Her eyes hovered somewhere over Wolcott Pond.

“I have too much packing, you know. I’ll need to leave on Thursday, if you can still give me a ride to the train in Montpelier. My gig with the Forest Service starts on the 20th, and I need to see my Mom down in Keene before I go.”

We’d been over the plan so many times. It’s finality hung in the air, and we didn’t speak about what lay beyond it, the plausibility of our fracture spanning the void of a thousand miles and a half-year apart.

“I should get some sleep anyway.” She turned back toward the car.

I lifted a bleached beaver chew from the mud and chucked it absently into the water. Tobey turned to chase, but though better of it. I opened my mouth to speak, but Jackie had already moved on. I followed her sucking footsteps away from the glimmer of dusk, and into a place fully dark.

I dropped her off at the dorm. There wasn’t anything to say, and she knew it and stepped out onto the grass. I followed her to the door, and reached for her and pulled her back and hugged her hard, hoping to find something in our immediacy, some understanding, but there was just the cool presence of her body and her hair against my lips as I awkwardly kissed her ear, and wanted to cry and couldn’t, and she pushed back and walked inside.

*

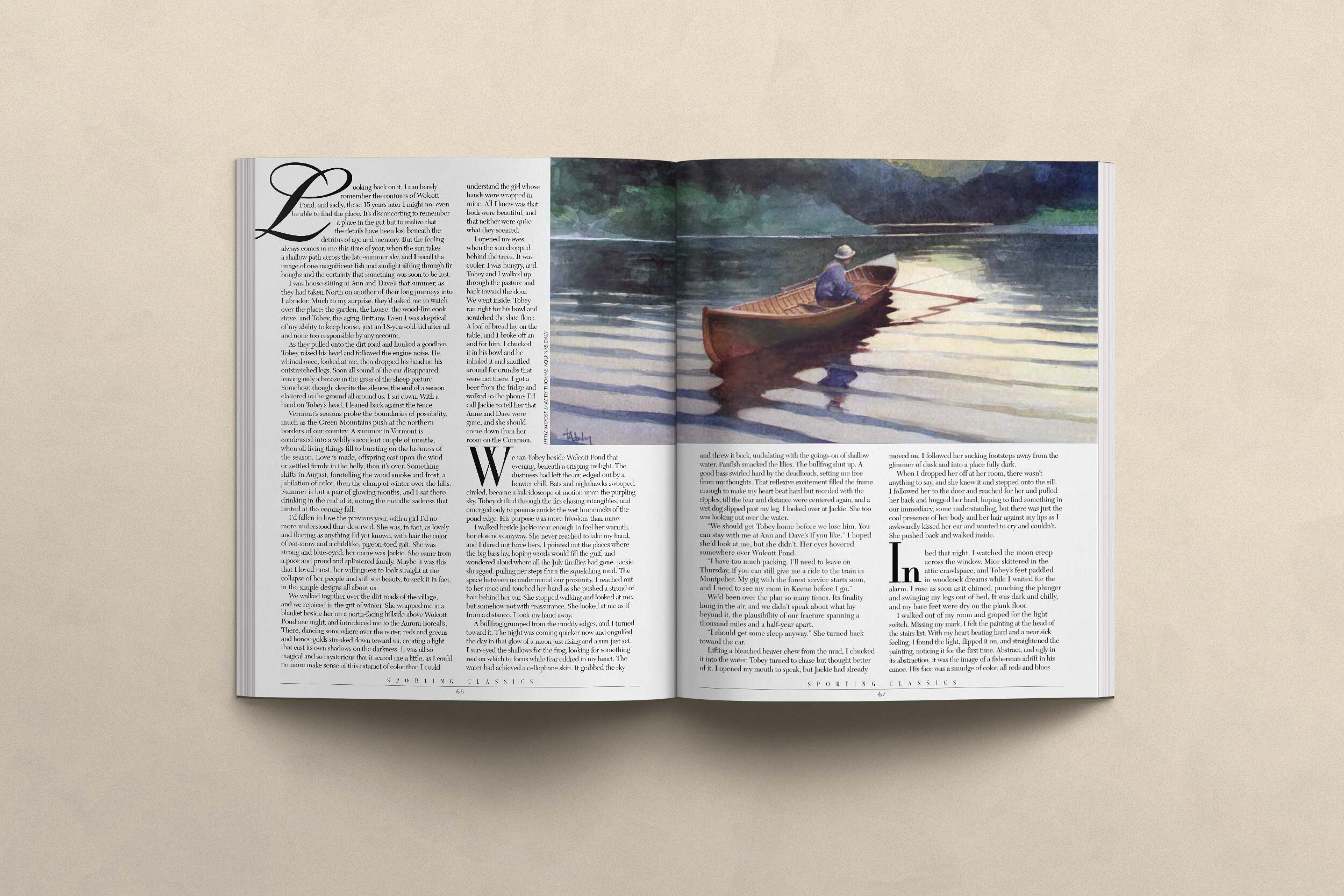

I lay in bed that night and watched the moon creep across the window. Mice skittered in the attic crawlspace, and Tobey’s feet paddled in woodcock dreams, while I waited for the alarm. I rose as soon as it chimed, punching the plunger and swinging my legs out of bed. It was dark and chilly, and my bare feet were dust-dry on the pine boards. I walked out of my room and groped for the light switch. Missing my mark, I felt the oil painting at the head of the stairs list sickeningly. I found the light with my heart beating hard and flipped it on, straightening the picture and noticing it for the first time. Abstract, and ugly in its abstraction, it was the loose image of a fisherman adrift in his canoe. His face was a mottled smudge of color absent of feeling, all reds and blues and grays. The rod in his hands was just a knife cut through layered paint, but it bent against the pull of a heavy fish. I went downstairs. The stove was cold, and I stirred the coals and put the kettle on to boil.

Under the same moon, I drove over the North Wolcott Road in the dark, with the radio on loud and my windows rolled up. Behind me, the first ream of pink was just showing over the White Mountains, and the sky was crisp with stars. It always seemed to be that as the nights grew colder, the stars shone clearer, as if the thick summer air had muffled them a bit. There were twists and turns over Town Hill that I can’t see now any more than I could see them then, and a hollowness in my heart that I still remember clearly. I pulled off the road beside Wolcott Pond just as the individual branches on the firs became distinct. There were moose tracks in the mud. I undid the half-hitches and swung the canoe off the car, and put together the sections of my old Orvis cane. I reached for the tea in the cup holder and took a long burning swallow that stung from the bourbon in it, then tossed it into the mud. I was not yet ready to think of myself as a morning drinker.

I worked the edge of the pond slowly, throwing a green and yellow bulls-eye popper in against the shore and chugging it back. It was a mindless sort of fishing that produced with enough regularity to make it seem reasonable, and I traced tangential lines around the margins of the pond as the sun rose. A sunrise is a wonderful thing at times, reminding all the world of the gently passing moments, and, in the early part of the day anyway, the possibility for nearly anything to make itself clear. A beaver waked against the far bank warning me with his tail, and I dipped a paddle here and there, working around to the cove that remained in shadow. There, the beaver chews stood stark and straight and skeletal, and somehow promising, and looking over at them, steadily getting closer, I felt ever more alone.

In moments of sheer and romantic melancholy, there is a substrate of truth that justifies the indulgence. Alone in the presence of absolute beauty and impending demise, I let the sadness wash over me. I breathed in the end of summer, and the necessity of a first lost love, and the departure of the first grown up year that I was intimate with. It was all so present to me, so available, so essential and acutely sacrificial and I just kept casting that old 5 weight, working closer and closer to the quietest, most still place. Against the rising sun, the reflection on the water was wholly undistorted, and the world became huge for a moment, and bright, and I became infinitesimally small. And then the reflection opened up, bending the colors into a vacuum that became shattered negatives of sky and hills and a monstrous, golden fish that was still going up, having scooped my popper en route to the sky.

A big fish can do funny things to a fisherman’s heart. In that moment, when the smallmouth crashed down and cut a vertical corner and headed for the snags, I had a moment to feel the weight of him, and the weight of the water, and the line in my fingers singing out, slick-wet and spastic. Jackie was gone then, alongside the sorrow and the Northern lights and the cavernous feeling, and there was instead a bile bitterness for this glorious fish that had become a presence in my morning. The burden of him, the superior secrecy, the lineage of a thousand Vermont autumns and catamount trails and beaver flows and moose tracks was all right there in a straight line to me, and the possibility of losing him was at once near, a presence beside me on the cane seat of the canoe, tangling the line that jumped from the coils around my feet. And I hated that fish for the potential of him, and decided then to cling to him at any cost, to let him run me clear over Wolcott Pond for the day if he wished, forcing me to miss whatever there was to miss back home. I’d stay there and win and take that fish in my hands and keep him forever, keep him safely in my sight, a stuffed and painted effigy on the wall that would never elude me, that would hang me in this summer forever, suspended in time.

The smallmouth came up fast and far out, and the line sliced the water, bowing as the fish outpaced it, designed better, as he was, for movement through water. He rose, and hovered against the morning in perfect profile, and I saw myself as an older man, watching the fish exactly like this, tacked up on a wall, in a world that had somehow moved along, growing temporally as the weight in my heart anchored me in youth. I clung to that image and cling to it still, and remember it perhaps more perfectly than I ever could have in the presence of a plasticky skin mount… but then, I have no choice. The fish tumbled back into Wolcott Pond and the electric heaviness departed the line and the popper burbled up to the surface to sit there still and nonsensical, among the deadheads and snags.

*

I miss Wolcott Pond in the way I miss summer, even as I sit against fence posts, aware of its passing. But age, and time, and moments that disappear slowly give back a peace with the things that slip silently, wordlessly, away. There is love there, among the Vermont hillsides, where Tobey now rests under the branches of a Northern Spy, turning back to rich black soil, and Wolcott Pond remains lost in the shadow of fir trees. And Jackie is there too somewhere, sifting through the Northern lights when the winter is coldest, and darkest, and more honest than cruel. And it is, perhaps, the most beautiful thing I’ve known: a peace with what we love and lose, and love the more for losing.

First Published in Sporting Classics