A Time of Quiet Wonder

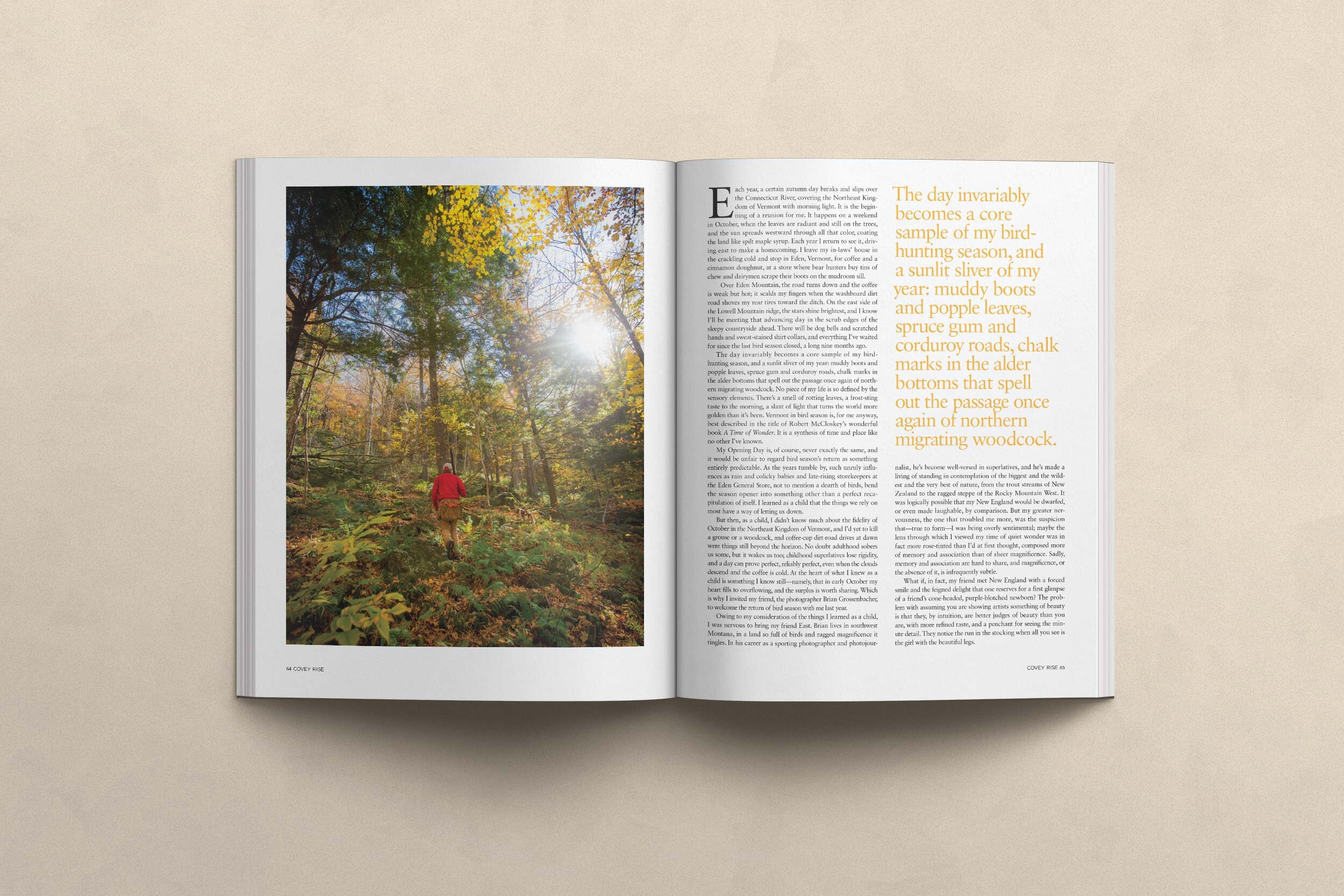

Each year, an autumn day breaks and slips over the Connecticut River, covering the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. It is the beginning of a reunion for me. It happens on a weekend in October, when the leaves are radiant and still largely on the trees, and the sun spreads westward through all that color, coating the land like spilt maple syrup. Each year I return to see it come, driving east to make a homecoming. I leave my in-law’s house in the crackling cold and stop in Eden, Vermont, for coffee and a cinnamon doughnut, at a store where bear hunters buy tins of chew and dairymen scrape their boots on the mudroom sill.

Over Eden Mountain, the road turns down and the coffee is weak but hot; it scalds my fingers when the washboard dirt shoves my rear tires toward the ditch. On the east side of the Lowell Mountain ridge, the stars shine brightest, and I know I’ll be meeting that advancing day in the scrub edges of the sleepy countryside ahead. There will be dog bells and scratched hands and sweat-stained shirt collars, and everything I’ve waited for since the last bird season closed, a long nine months before.

The day invariably becomes a core sample of my bird-hunting season, and a sunlit sliver of my year: muddy boots and popple leaves, spruce gum and corduroy roads, chalk marks in the alder bottoms that spell out the passage of migrating woodcock. No piece of my life is so defined by the sensory elements. There’s a smell of rotting leaves, a frost-sting taste to the morning, a slant of light that turns the world more golden than it’s been. Vermont in bird season is, for me anyway, best described in what Robert McCloskey called ‘a time of quiet wonder’. It is a synthesis of time and place like no other I’ve known.

My opener is, of course, never exactly the same, and it would be unfair to regard bird season’s return as something entirely predictable. As the years tumble by, such unruly things as rain and colicky babies and late-rising storekeepers at the Eden General Store, not to mention a dearth of birds, bend my opening day into something other than a perfect recapitulation of itself. I learned as a child that the things we rely on hardest have a way of letting us down.

But then, as a child, I didn’t know much about the fidelity of October in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, and I’d yet to kill a grouse or woodcock, and coffee-cup dirt-road drives in the dawn were things still beyond the horizon. No doubt adulthood sobers us some, but it wakes us too; childhood superlatives lose rigidity, and a day can prove perfect, reliably perfect, even when the clouds descend and the coffee is cold. At the heart of what I knew as a child is something I know still—namely, that in early October my heart fills to overflowing, and the surplus is worth sharing. Which is why I invited my friend, the photographer Brian Grossenbacher, to welcome the return of bird season with me this past year.

Owing to my consideration of the things I learned as a child, I was nervous to bring my friend East. My trepidation was two-fold: for one, Brian lives in southwest Montana, in a land so full of birds and ragged magnificence it tingles. In his career as a sporting photographer and photojournalist, he’s become well-versed in superlatives, and he’s made a living of standing in contemplation of the biggest and the wildest and the very best of nature, from the trout streams of New Zealand to the ragged steppe of the Rocky mountain West. It was logically possible that my New England would be dwarfed, or even made laughable, by comparison. But my greater nervousness, the one that troubled me more, was the suspicion that, true to form, I was just being overly sentimental; maybe the lens through which I viewed my ‘time of quiet wonder’ was in fact more rose-tinted than I’d at first thought, composed more of memory and association than sheer magnificence. Sadly, memory and association are hard to share, and magnificence, or the absence of it, is infrequently subtle.

What if, in fact, my friend met New England with a forced smile and the feigned delight that one reserves for a first glimpse of a friend’s cone-headed, purpled newborn? The problem with assuming you are showing an artist something of beauty is that they, by intuition, are better judges of beauty than you, with more refined taste, and a penchant for seeing the minute detail. They notice the run in the stocking when all you see is the girl with the beautiful legs.

True to form, I kept tugging that thread of insecurity. I’d hunted with Brian before, in places that didn’t rely on the nuances of texture or local dialect to find your heart. In Alaska there were planes and volcanoes and remarkable skies that went from blue to bruised purple in an instant. There were ptarmigan by the hundred and ducks by the thousand, and second, third, fourth chances to line up the perfect shot. In Argentina there were tumbling estates and Ombu trees that made a mockery of men and dogs, and ducks painted up like Malay dancers. These were the things that Brian, I feared, had grown accustomed to: things so big and bright that even on paper the image of them roared. I trusted my friend, and his uncanny ability to tease the beauty out of every frame, but I was nonetheless banking on the beauty of stale coffee and manure tang and small hills; that, and the likely prospect of little more than a small handful of feathers.

I thought these things after the tickets were bought and Brian was on a plane East. I thought them and was ashamed of my disloyalty to the most beautiful thing I know, ashamed of my insecurity. I thought them long enough to realize that they couldn’t be helped, and then I met my friend at the Eden General Store, with a scalding cup of weak coffee and a cinnamon doughnut. He was bleary from travel and laden down with cameras, but optimistic. After all, I’d been selling this place, selling the resplendent colors and hill farms and partridge-filled thickets to him for years.

We wound our way out into the rising day, and on the downhill side of the Lowell Mountains the land opened up to us. The sun filled the frame and the leaves were just as much a burst of red-gold as I’d needed them to be, though the best of the color had fallen to the ground already.

Wisps of smoke rose from the farmhouses and the hump of Big Jay Peak (a well-known ski area in Northern Vermont, not far from the Quebec border), hard against a foreign land, loomed in the west, and the cinnamon donuts, cellophane wrapped and stale, were just as good as God intended. My bird season was upon us once more, my friend was here to see it, and the day was just beginning. Brian and I made the rounds through the morning, revisiting acquaintances through the hamlet of Craftsbury, Vermont, and confirming permission to land, having the small talk that one has with the folks that offer up their birds and their back pastures. These were friends I’d made in the time when and since I’d lived there, friends I’d seen each year in fall for more years than I’d care to admit. They’d themselves become a part of the season. In their dooryards I’d watched their children grow, their barns collapse, they themselves go gray around the temples.

Brian could not have known those things, but he laughed at their jokes no less, smiled at their skepticism, accepted their apple cider and sidelong glances. By mid-morning, we had gained consent to a festival of coverts, and we fell upon the hunting in earnest.

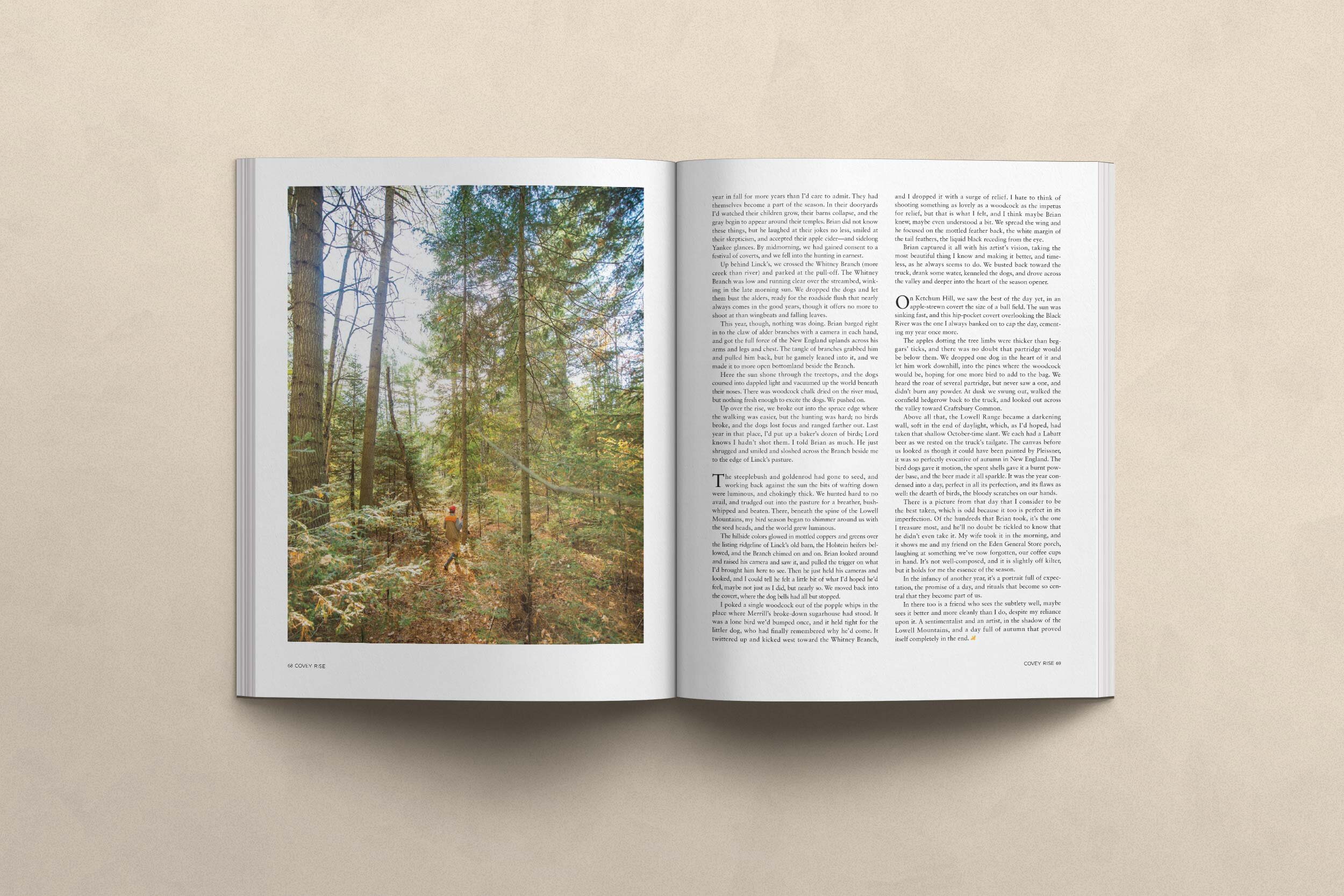

Up behind Linck’s, we crossed the Whitney Branch (more creek than river) and parked at the pull-off. The Whitney Branch was low and ringing clear over the streambed, winking in the late morning sun. We dropped the dogs and let them bust the alders, ready for the roadside flush that nearly always comes in the good years, though it offers no more to shoot at than wingbeats and falling leaves.

This year, though, nothing was doing. Brian barged right in to the claw of alder branches with a camera in each hand, and got the full force of the New England uplands across his arms and legs and chest. The tangle of branches grabbed him and pulled him back, but he gamely leaned into it, and we made it to more open bottomland beside the Branch.

Here the sun shone through the treetops, and the dogs coursed into dappled light, and vacuumed up the world beneath their noses. There was woodcock chalk dried on the river mud, but nothing fresh enough to excite the dogs. We pushed on.

Up over the rise, we broke out into the spruce edge where the walking was easier, but the hunting was hard; no birds broke, and the dogs lost focus and ranged further out. Last year in that place I’d put up a baker’s dozen of birds, but they’d dried up or left; Lord knows I hadn’t shot them. I told Brian as much. He just shrugged and smiled and sloshed across the Branch beside me to the edge of Linck’s pasture.

The steeplebush and goldenrod had gone to seed, and working back against the sun the bits of wafting down were luminous, and chokingly thick. We hunted hard to no avail, and trudged out into the pasture for a breather, bush-whipped and beaten. There, beneath the spine of the Lowell Mountains, my bird season began to shimmer around us with the seed heads, and the world grew luminous too.

The hillside colors glowed in mottled coppers and greens over the listing ridgeline of Linck’s old barn, the Holstein heifers bellowed, and the Branch chimed on and on. Brian looked around and raised his camera and saw it, and pulled the trigger on what I’d brought him here to see. Then he just held his cameras and looked, and I could tell he felt a little bit of what I’d hoped he’d feel, maybe not just as I did, but nearly so. We moved back into the covert, where the dog bells had all but stopped.

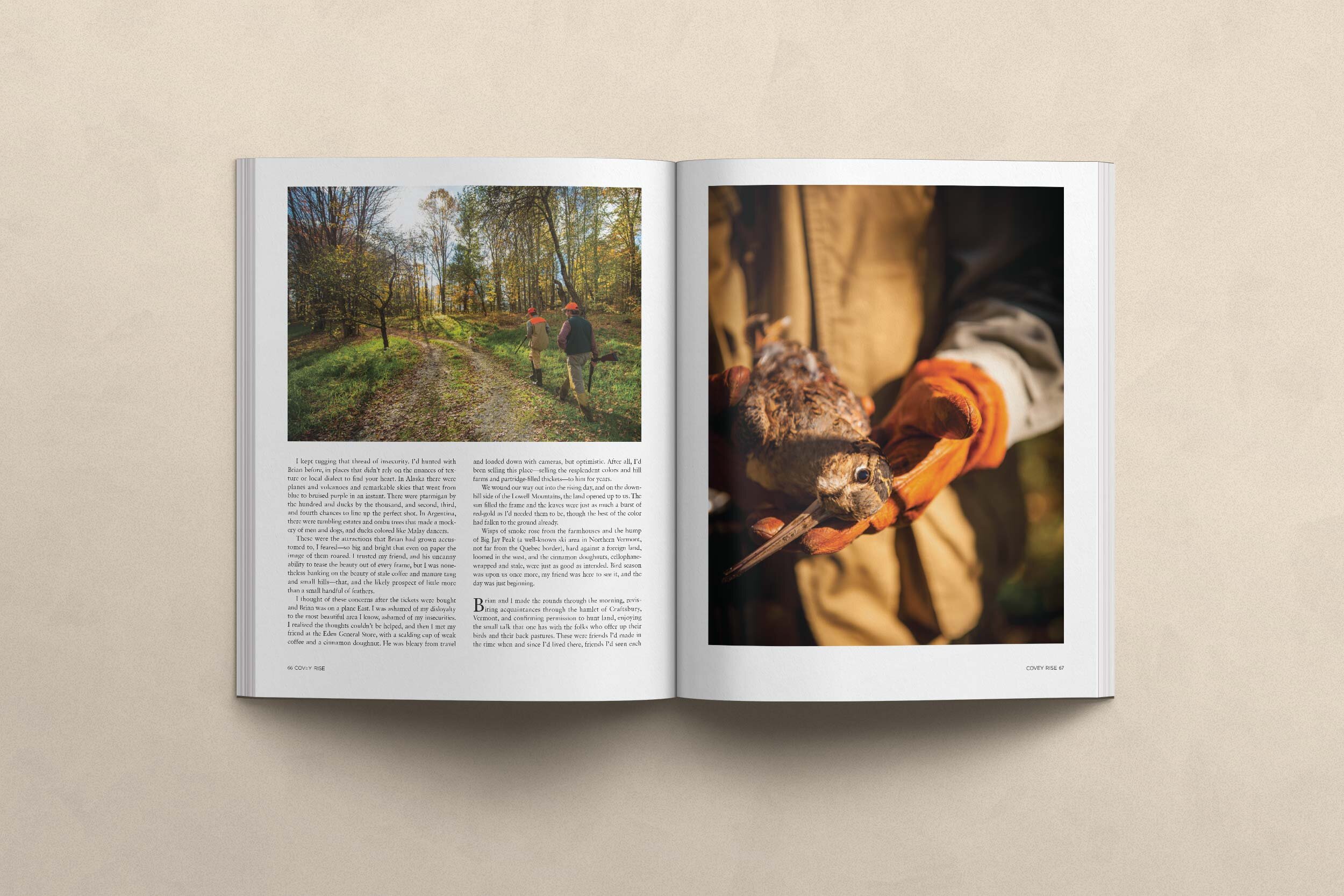

I poked a single woodcock out of the popple whips in the place where Merrill’s broke-down sugarhouse had stood. It was a lone bird we’d bumped once, and it held tight for the littler dog, who had finally remembered why he’d come. It twittered up and kicked west toward the Whitney Branch, and I dropped it with a surge of relief. I hate to think of shooting something as lovely as a woodcock as the impetus for relief, but that is what I felt, and I think maybe Brian knew, maybe even understood a bit. We spread the wing and he focused on the mottled feather back, the white margin of the tail feathers, the liquid black receding from the eye. Brian captured it all with that artist’s eye, taking the most beautiful thing I know and making it better, and timeless, as he always seems to do. We busted back toward the truck and drank some water, kenneled the dogs, and drove across the valley and deeper into the heart of the opener. On Ketchum Hill, we saw the best of it, in an apple-strewn covert the size of a ball field. The sun was sinking fast, and this hip-pocket covert overlooking the Black River was the one I always banked on to cap the day, cementing my year once more.

The apples were thicker than beggars’ ticks, and there was no doubt that the partridge would be in them. We dropped one dog in the heart of it and let him work downhill, into the pines where the woodcock would lie, hoping for one more bird to fill the bag. We heard the roar of several partridge, but never saw a one, and didn’t burn any powder. At dusk we swung out, walked the cornfield hedgerow back to the truck, and looked out across the Valley toward Craftsbury Common. Above all that, the Lowell Range became a darkening wall, soft in the end of day light which, as I’d hoped, had taken that shallow October-time slant. We each had a Labatt beer as we rested on the truck's tailgate. The canvas before us looked as though it could have been painted by Pleissner, it was so perfectly evocative of autumn in New England. The bird dogs gave it motion, the spent shells gave it a burnt powder base, and the beer made it all sparkle. It was the year condensed into a day, perfect in all of its perfection, and its flaws as well: the dearth of birds, the bloody scratches on our hands.

There is a picture from that day that I consider the best one taken, which is odd because it too is perfect in its imperfection. Of the hundreds that Brian took, it’s the one I treasure most, and he’ll no doubt be tickled to know that he didn’t even take it. My wife took it in the morning, and it shows my friend and I on the General Store porch, laughing at something we’ve now forgotten, our coffee cups in hand. It’s not well-composed, and it is slightly off kilter, but it holds for me the essence of the season.

In the infancy of another year, it’s a portrait full of expectation, the promise of a day, and rituals that become so central that they become a part of us. In there too is a friend who sees the subtlety well, maybe sees it better and more cleanly than I do, despite my reliance upon it. A sentimentalist and an artist, in the shadow of the Lowell Mountains, and a day full of autumn that proved itself completely in the end.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine