Flawless Function

In considering artistry, my mind wanders to an oft-referenced story about chef David Chang, the specifics of which I will undoubtedly butcher.

It is said that some years ago, in the heat of a dinner rush at Chang’s definitive Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York City, a young sous chef made the error of chopping green onions to irregular size before heaping them casually in the mise en place.

Upon noticing this gross negligence, Chang gave the kid a thorough dressing down.

The sous chef was caught off-balance: “But the onions go on the bottom of the bowl,” he apparently said, scrambling to save face. “Under the noodles, under the broth, under the egg, under the pork belly… No one will ever even see them!”

To which, legend has it, Chang went black in the eyes and replied:

“That is exactly why they need to be perfect.”

Chang’s response is evidence of something that defines artists, something independent of compulsion or ego. Incorrect green onions violated a cornerstone of integrity, dishonored a tradition that was, is, about far more than noodle soup. His response is also descriptive of a conviction that was arrived upon personally: great artists are curious enough to differentiate the mundane from the exquisite, or possibly to see the exquisite in the mundane. In a lifetime eating noodles, I’d venture that David Chang explored the bottom of a bowl once or twice to find some green onions chopped precisely, and some, well, not so much. I bet green onions taught him something about the chef he wanted to be.

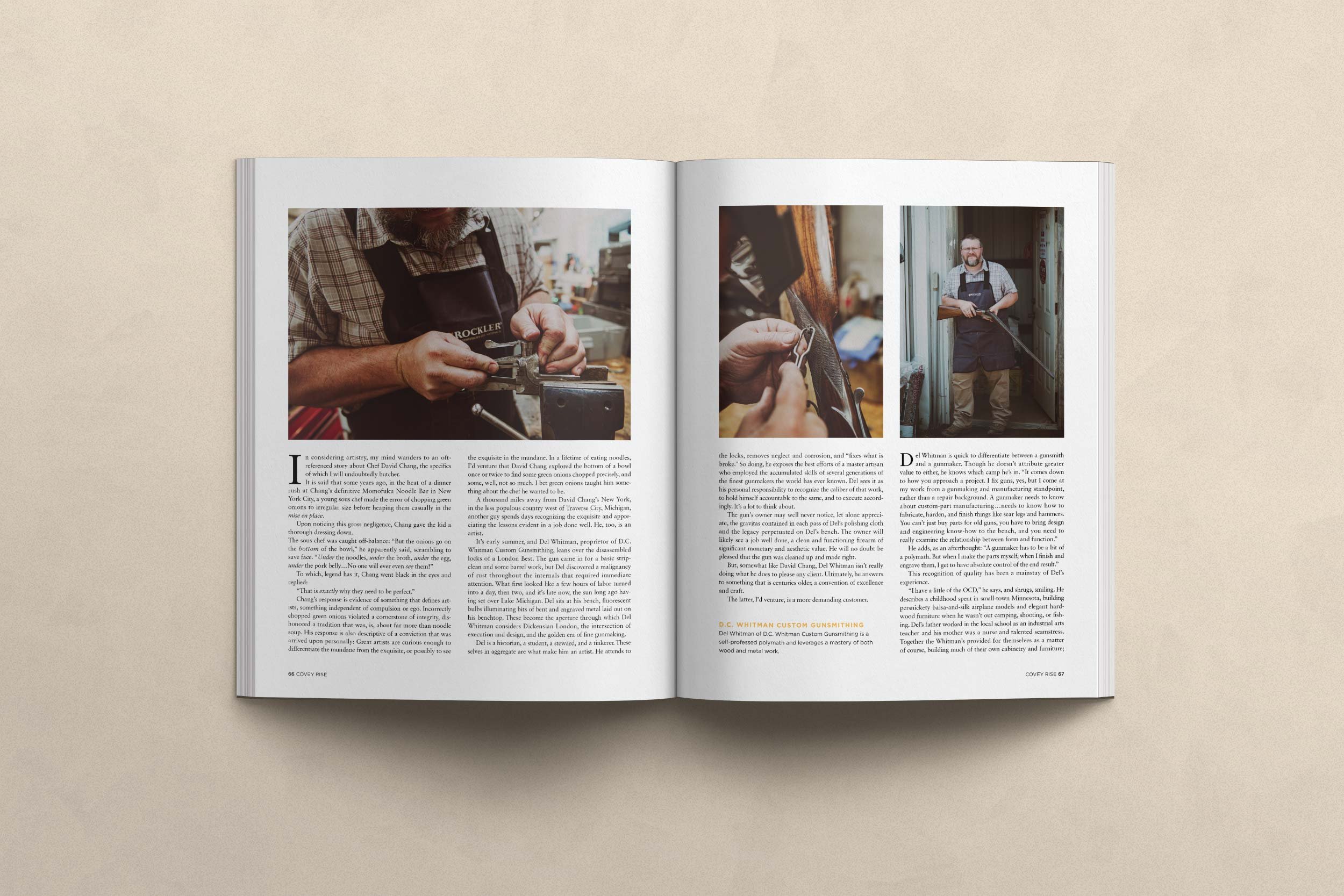

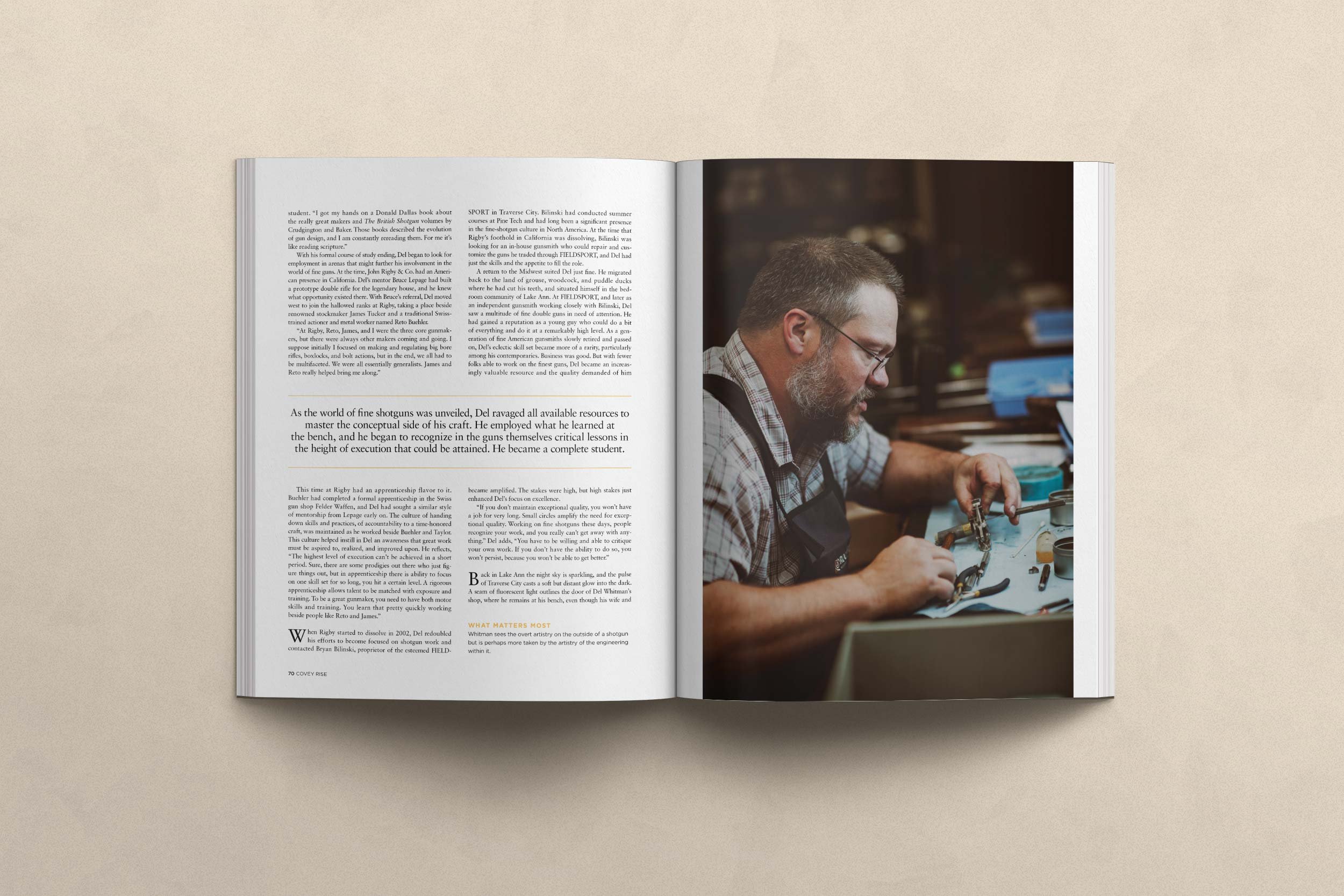

A thousand miles away from David Chang’s New York, in the less populous country west[1] of Traverse City, MI, another guy spends days recognizing the exquisite, and appreciating the lessons evident in a job done well. He too is an artist. It’s early summer, and Del Whitman, proprietor of D.C. Whitman Custom Gunsmithing, leans over the disassembled locks of a London Best. The gun came in for a basic strip-clean and some barrel work, but Del discovered a malignancy of rust throughout the internals that required immediate attention. What first looked like a few hours ’labor turned into a day, then two, and it’s late now, the sun long ago having set over Lake Michigan. Del sits at his bench, fluorescent bulbs illuminating bits of bent and engraved metal laid out on his benchtop. These become the aperture through which Del Whitman considers Dickensian London, the intersection of execution and design, and the golden era of fine gunmaking.

Del is an historian, a student, a steward, and a tinkerer. These selves in aggregate are what make him an artist. He attends to the locks, removes neglect and corrosion, and “fixes what is broke”. So doing he exposes the best efforts of a master artisan who employed the accumulated skills of several generations of the finest gunmakers the world has ever known. Del sees it as his personal responsibility to recognize the caliber of that work, to hold himself accountable to the same, and to execute accordingly. It’s a lot to think about.

The gun’s owner may well never notice, let alone appreciate, the gravitas contained in each pass of Del’s polishing cloth, and the legacy perpetuated on Del’s bench. The owner will likely see a job well done, a clean and functioning firearm of significant monetary and aesthetic value. He will no doubt be pleased that the gun was cleaned up and made right.

But, somewhat like David Chang, Del Whitman isn’t really doing what he does to please any client. Ultimately, he answers to something that is centuries older, a convention of excellence and craft.

The latter, I’d venture, is a more demanding customer.

*

Del Whitman is quick to differentiate between a gunsmith and a gunmaker. Though he doesn’t attribute greater value to either, he knows which camp he’s in. “It comes down to how you approach a project. I fix guns, yes, but I come at my work from a gunmaking and manufacturing standpoint, rather than a repair background. A gunmaker needs to know about custom part manufacturing… needs to know how to fabricate, harden, and finish things like sear legs and hammers. You can’t just buy parts for old guns; you have to bring design and engineering know-how to the bench, and you need to really examine the relationship between form and function.”

He adds, as an afterthought, “A gunmaker has to be a bit of a polymath. But when I make the parts myself, when I finish and engrave them, I get to have absolute control of the end result.”

This recognition of quality has been a mainstay of Del’s experience.

“I have a little of the OCD,” he says, and shrugs, smiling. He describes a childhood spent in small-town Minnesota, building persnickety balsa-and-silk airplane models and elegant hardwood furniture when he wasn’t out camping, shooting, or fishing. Del’s father worked in the local school as an industrial arts teacher and his mother was a nurse[2] and talented seamstress; together the Whitman’s provided for themselves as a matter of course, building much of their own cabinetry and furniture, hunting fishing and foraging, fixing what broke. Implicit in this work was reverence for a job done right for its own sake, and attention was paid both to craft and to the symbiosis between form and function. The standard of execution was high; Del learned that a house filled with hand-made things afforded ample opportunity to contemplate how things could be made even better. He had plenty of time to dwell on un-sanded mill marks and gaps in the joinery, and plenty of time to be satisfied about those pieces that held up over time.

Del regularly accompanied his dad to school, arriving early and staying late. In those hours he was set free to explore the industrial arts shops. The school funded these programs well, and had outfitted a full wood and machine shop, installed lathes, machine tools, and a small aluminum foundry. “I was oxyacetylene welding by 6th grade,” says Del matter-of-factly, as if all 11-year-olds are capable of the highly dangerous and finicky work. When high-school graduation loomed, he began to think about options that would enable him to remain in contact with wood and metal, that would allow him to integrate design, engineering, and handwork in the production of something elegant. He had enjoyed guns throughout his youth and had shot extensively at his local gun club[3] . Pine Technical & Community College in nearby Pine City, MN, offered a noteworthy gunsmithing program, and seemed an obvious path to pursue.

Del arrived at Pine Tech with a formidable skill set that encompassed wood and metal work, but his aptitude for the intangibles of aesthetic quality quickly caught the eye of instructor Bruce Lepage. Lepage, himself a master gunmaker and metallurgist, saw in Del an appetite for more than basic repair and maintenance of rifles and pistols. He steered his student towards work on fine muzzleloaders and shotguns, and he opened a virtual Pandora’s box.

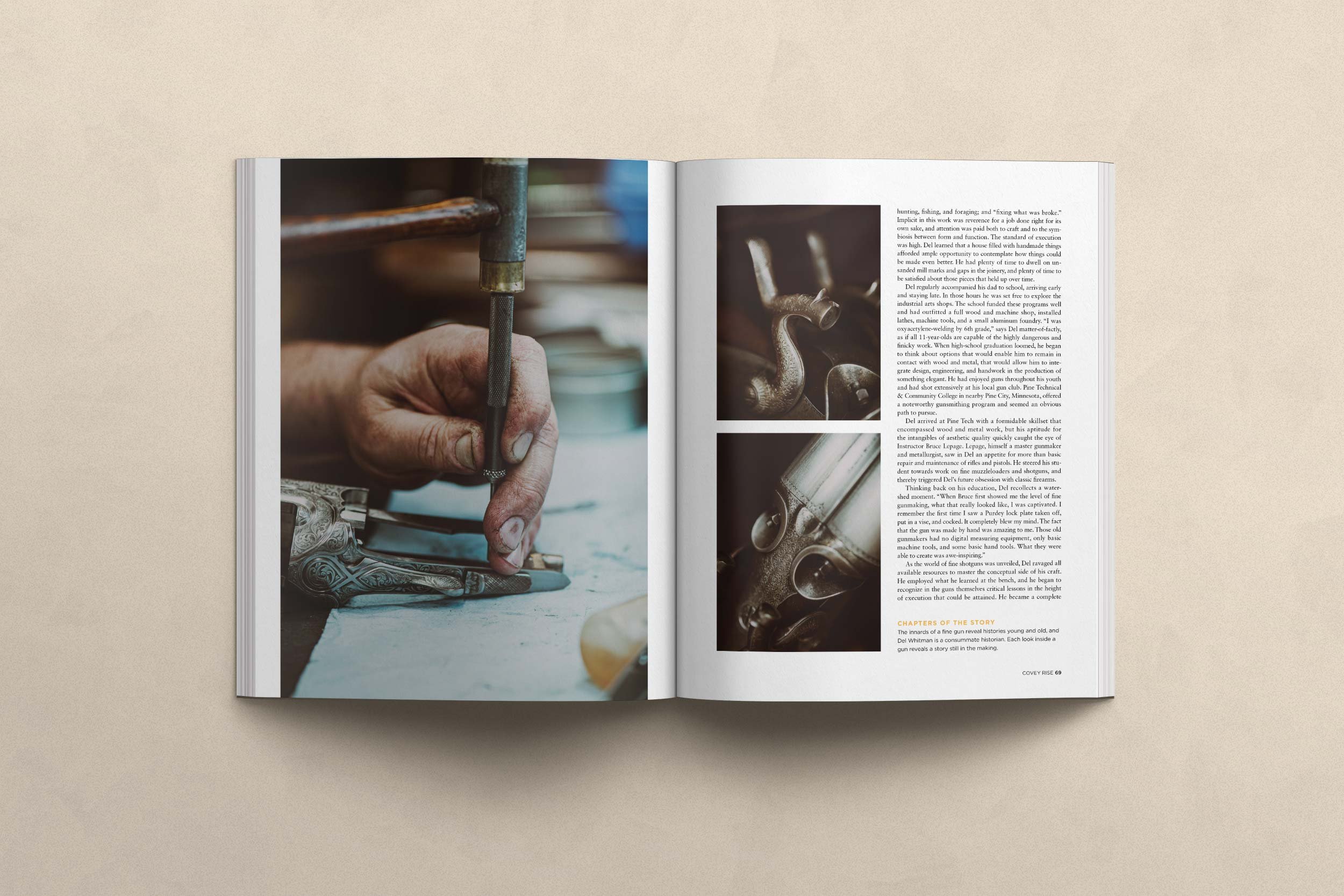

Thinking back on his education, Del recollects a watershed moment. “When Bruce first showed me the level of fine gunmaking, what that really looked like, I was captivated. I remember the first time I saw a Purdey lock plate taken off, put in a vise, and cocked. It completely blew my mind. The fact that the gun was made by hand was amazing to me; those old gunmakers had no digital measuring equipment, only basic machine tools, and some basic hand tools. What they were able to create was awe-inspiring.”

As the world of fine shotguns was unveiled, Del ravaged all available resources to master the conceptual side of his craft. He employed what he learned at the bench, and he began to recognize in the guns themselves critical lessons in the height of execution that could be attained. He became a complete student. “I got my hands on Donald Dallas’ books about the really great makers, and The British Shotgun volumes by Cruddington & Baker. Those books described the evolution of gun design, and I am constantly re-reading them. For me it’s like reading scripture.”

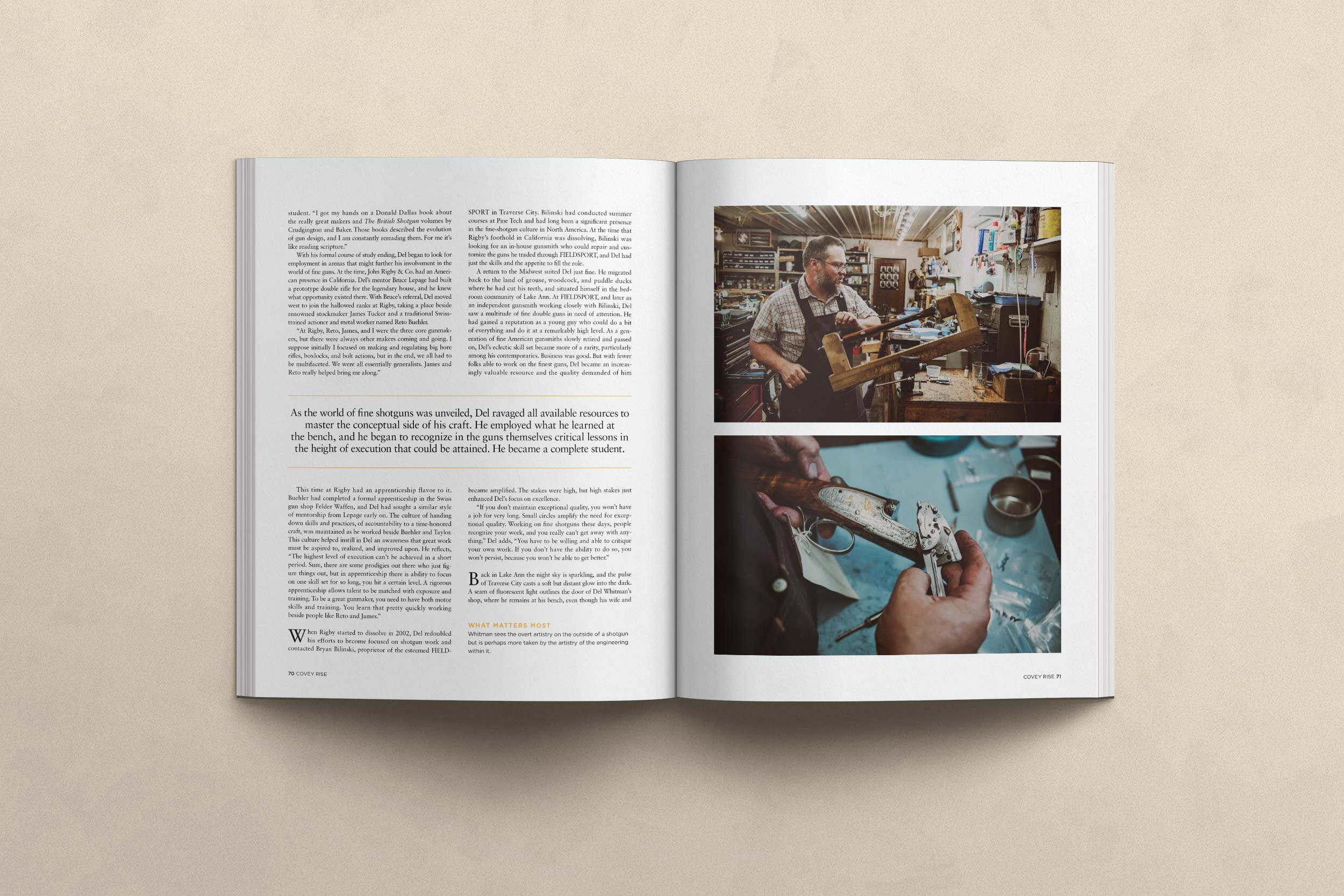

With his formal course of study ending, Del began to look for employment in arenas that might further his involvement in the world of fine guns. At the time, John Rigby & Co. had an American presence in California. Del’s mentor Bruce Lepage had built a prototype double rifle for the legendary house, and he knew what opportunity existed there. With Bruce’s referral, Del moved west to join the hallowed ranks at Rigby, taking a place beside renowned stockmaker James Tucker and a traditional Swiss-trained actioner/metal worker named Reto Buehler.

“At Rigby, Reto, James and I were the core three gunmakers, but there were always other makers coming and going. I suppose initially I focused on making and regulating big bore rifles, boxlocks and bolt-action, but in the end, we all had to be multi-faceted. We were all essentially generalists. James and Reto really helped bring me along.”

This time at Rigby had an apprenticeship flavor to it. Buehler had completed a formal apprenticeship in the Swiss gun shop "Felder Waffen", and Del had sought a similar style of mentorship from Lepage early on. The culture of handing down skills and practices, of accountability to a time-honored craft, was maintained as he worked beside Buehler and Taylor. This culture helped instill in Del an awareness that great work must be aspired to, realized, and improved upon. He reflects, “the highest level of execution can’t be achieved in a short period. Sure, there are some prodigies out there who just figure things out, but in apprenticeship there is ability to focus on one skillset for so long, you hit a certain level. A rigorous apprenticeship allows talent to be matched with exposure and training. To be a great gunmaker you need to have both motor skills and training. You learn that pretty quickly working beside people like Reto and James.”

*

When Rigby started to dissolve in 2004 , Del redoubled his efforts to become focused on shotgun work and contacted Brian Bilinski, proprietor of the esteemed Fieldsport in Traverse City. Bilinski had conducted summer courses at Pine Tech and had long been a significant presence in the fine shotgun culture extant in North America. At the time that Rigby’s foothold in California was dissolving, Bilinski was looking for an in-house gunsmith that could repair and customize the guns he traded through Fieldsport, and Del had just the skills and the appetite to fill the role.

A return to the Midwest suited Del just fine. He migrated back to the land of grouse, woodcock, and puddle ducks where he had cut his teeth, and situated himself in the bedroom community of Lake Ann. At Fieldsport, and later as an independent gunsmith working closely with Bilinski, Del saw a multitude of fine double guns in need of attention. He had gained a reputation as a young guy who could do a bit of everything and do it at a remarkably high level. As a generation of fine American gunsmiths slowly retired and passed on, Del’s eclectic skill set became more of a rarity, particularly among his contemporaries. Business was good. But with fewer folks able to work on the finest guns Del became an increasingly valuable resource and the quality demanded of him became amplified; the stakes were high, but high stakes just enhanced Del’s focus on excellence.

“If you don’t maintain exceptional quality, you won’t have a job for very long. Small circles amplify the need for exceptional quality. Working on fine shotguns these days, people recognize your work, and you really can’t get away with anything.” To which he adds, “you have to be willing and able to critique your own work. If you don’t have the ability to do so, you won’t persist, because you won’t be able to get better.”

*

Back in Lake Ann the night sky is sparkling, and the pulse of Traverse City casts a soft but distant glow into the dark. A seam of fluorescent light outlines the door of Del Whitman’s shop, where he remains at his bench, even though his wife and kid[5] have gone to bed. He hopes to get outside for a little in the morning, to tend to his young tomato plants, and to look after his beehives. But on the bench the disassembled locks still have a grip on him. The corrosion is slowly and painstakingly being reduced to dust, and gleaming metal is emerging once again, in tribute to its original grandeur. These are the things that keep Del up past his bedtime; he respects the work that came before enough to demand of himself something at least as good or better. Maybe, in the dark of a Michigan night, he is just keeping league with the ghosts of gunmakers past.

Del frames what he does in an interesting way, sort of like David Chang, or any artist for that matter. When you talk to him, and he absently describes what he finds so endlessly beautiful and complex in the guns he works on, you realize how multi-dimensional his world is, and how completely he interprets it. When asked what he sees in the complication of metal on his bench, he picks up a lock plate, focuses not on the exquisite scroll on the outside, but on the threaded holes and burnished wear marks evidenced on the inside face. He is captivated by the pieces that very few people look at. “You really have to understand the historical context to appreciate all that is here. You get a look at the big picture… what was the machine technology that was available when this was made? How was it possible that the makers could create such intricate[6] lock parts, could reach this height of design? If you don’t look beneath the surface, you lose the plot entirely...”

He pauses and thinks about this for a second, then puts the lock plate back down, and continues polishing. All around him are the collective tools of a trade, the historical references, the lotions and positions of an alchemist. There are guns waiting their turn in his hands, and broken parts in need of careful replication, hardening, engraving. There are raw stocks in want of final finishing, and walnut grain that will soon come ablaze with a first coat of oil. There is a lot lingering beneath the surface of both the artist and the work in which he is immersed. “I just like things that function flawlessly,” he says and gets up, flips of the overhead lights, walks the shop door. In the morning he’ll make time to water his tomatoes, to add frames to his hives. Likely he’ll finish and re-assemble the London gun, pack it carefully for shipment back to its owner. His are small and essential tasks… done to an exquisite degree.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine