Peaches in the Summertime Apples in the Fall

NYC food blogger Julia Estrada is perhaps less lyrical than I’d like in explaining sourdough starter.

“It’s an active colony of wild yeast and good bacteria cultivated by combining flour and water and allowing it to ferment,” she says. “By feeding it and keeping it in happy conditions you will have a reliable ‘natural yeast’ culture that can be used to leaven breads and pastries of all kinds. As you refresh the starter with new ‘food’ (i.e. flour and water) each microbe gets stronger and more vivacious.”

There’s sound middle-school science in that definition, and a slightly less obvious allegory: introduce some honest players, expose them to the magic that abounds in a place, and have faith. With food and drink, warmth and love, the resulting community will grow stronger and more vivacious with every passing day.

What Estrada leaves out of her definition is the ambient magic available in vehicles as common as bread. The ‘natural yeasts’ she refers to inhabit the spaces we can’t see. These yeasts represent myriad disparate strains, but when a welcoming home is offered, they will take up residence nearby, revealing themselves in fermented, living, or risen foods. Each yeast imparts its own essence; in a sourdough starter, the marriage of yeast and flour and water takes on the subtle flavor of a place. A jar of flour and water left on a San Francisco rooftop is colonized by certain yeasts that are distant relatives of those that colonize a jar left to rest on an Anchorage porch rail. Each can inform a lifetime of unique loaves and slices, pulled hot from the oven to fill bellies with love made manifest.

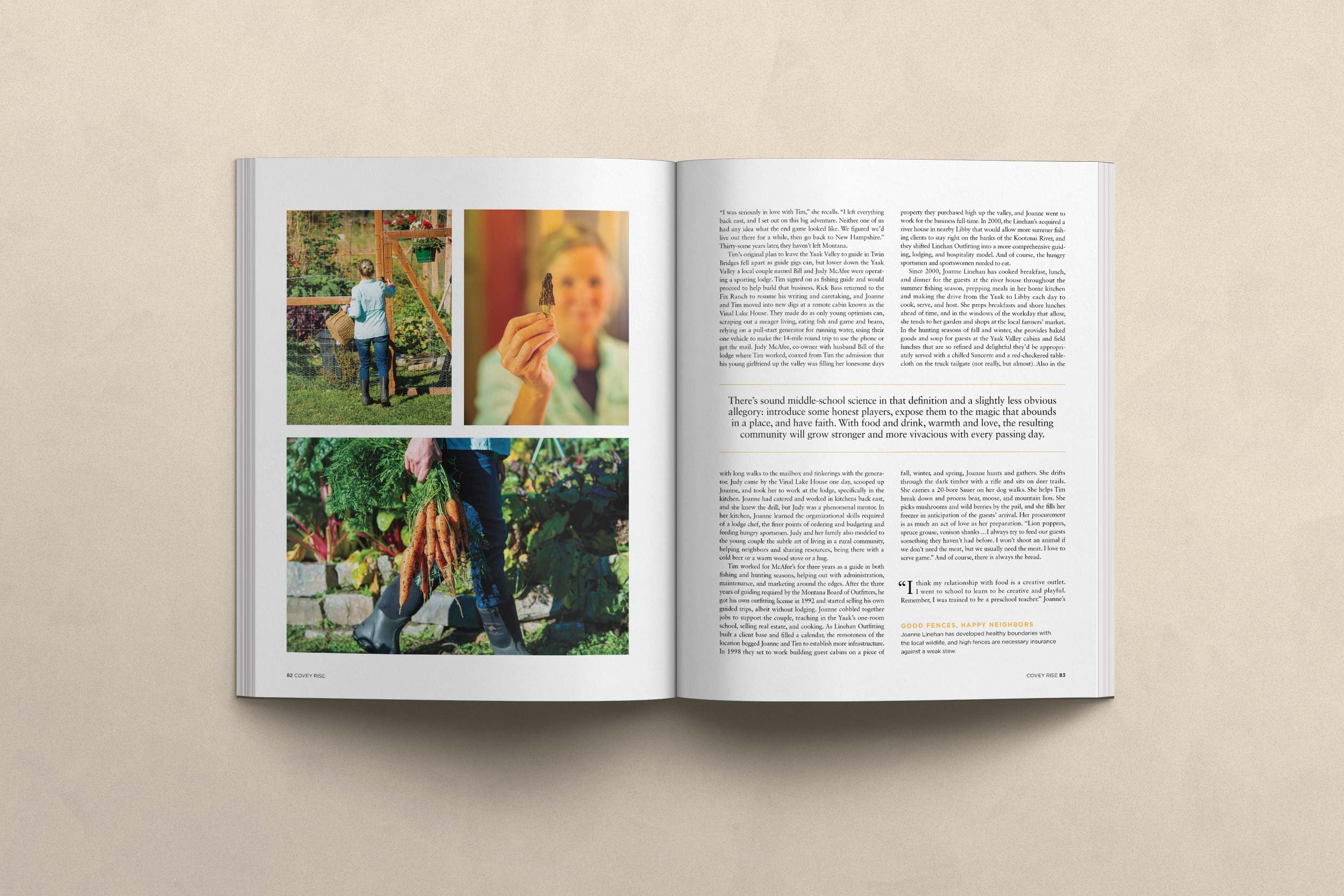

Years back, Joanne Linehan used King Arthur Flour and Montana well water to make her sourdough starter. She mixed those ingredients in a Ball jar, walked into her dooryard, and held the jar of goop in both hands, persuading the wild yeasts of Montana’s Yaak Valley to join her. I have no idea what a wild yeast looks like, but I imagine they resemble fireflies, luminous and flitting, predisposed to do good work. If wild yeasts are sentient, I’d think they descended from on high into Joanne Linehan’s Ball jar wholly willing, recognizing that in her care they’d be fed and loved and tended to, made a part of lovely gestures. In my imagination, Joanne stood in the sunshine with her eyes bright and her heart open, welcoming the gifts of the Yaak, knowing that she might both nourish them and be nourished too.

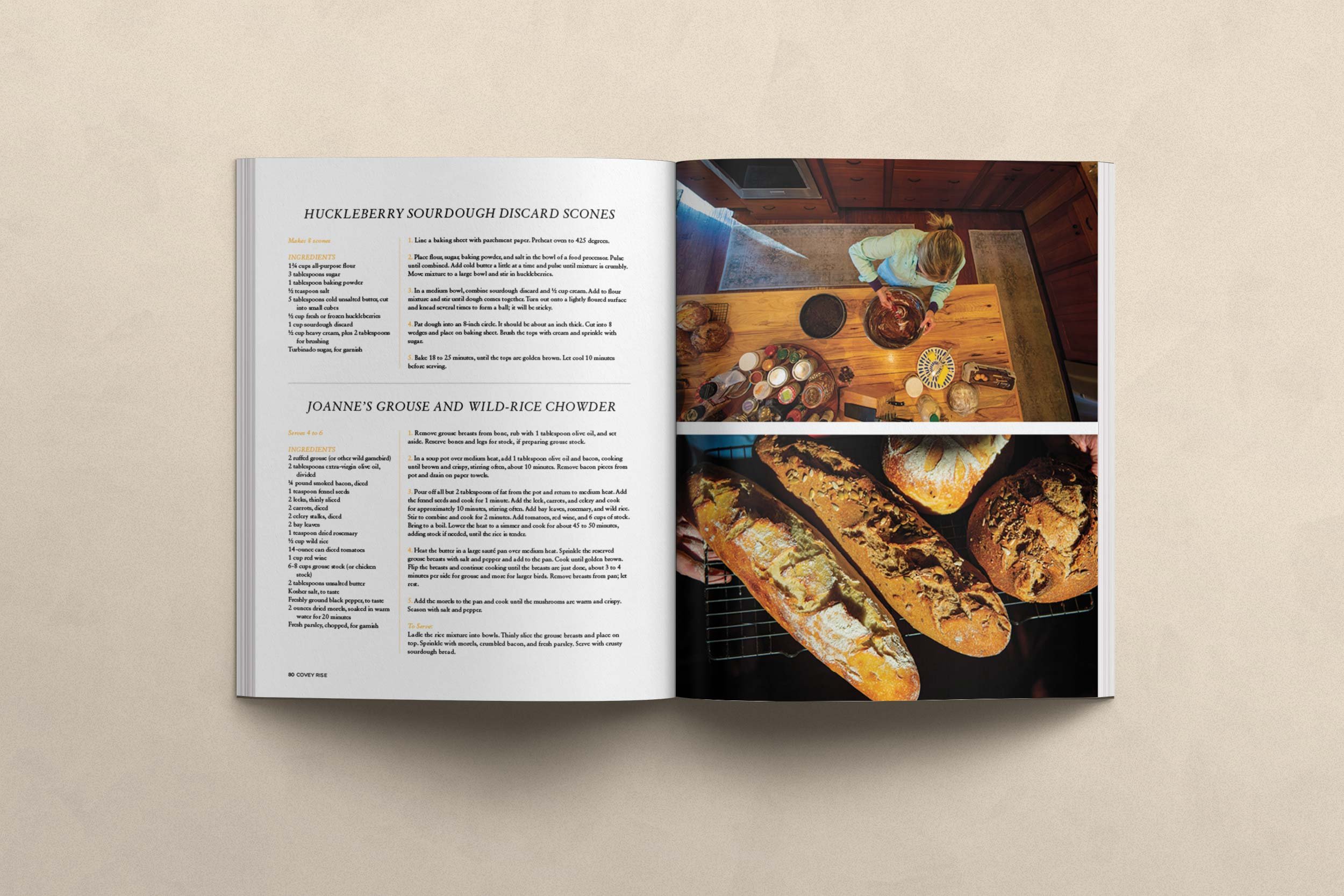

Metaphors, magic, and fireflies aside, Joanne takes her sourdough seriously. She feeds her starter as she feeds the guests of Linehan Outfitting, the business she owns with her husband, Tim. In mid-morning, after her bird dogs are tended to and Tim has departed for the woods or the water, Joanne removes ½ of the active starter from its jar and plops it into a bowl. She replenishes what she has taken with another measure of water and flour, nourishing her starter for another day, ensuring its vivacity. She adds water and flour to the starter in the bowl, mixes, and separates the dough into four small rounds. Those are left to rise. She will punch them and knead them at points through the workday, letting the final rise occur as she and Tim and the dogs sleep. Come sunrise she will pre-heat the kitchen oven, and as the dog bowls are filled and the coffee is made, the loaves will bake, swelling over the pan tops, the surface going crusty and gold. As other morning rites unfurl throughout the Yaak Valley, the loaves will be pulled and sliced, made into sandwiches and slabs of toast slathered with butter and honey. Tim will leave for the woods or the water, his cooler heavy with wonderful things, and Joanne will turn to the jar on her countertop, the one burbling with happy yeasts and flour and Montana well water. She will smile. Come mid-morning, the process will begin anew, sure as the sun rises and sets.

“It’s a continuum. It’s my meditation,” she says, her green eyes smiling.

I’d say it’s a gesture of something far bigger, something that defines both Joanne Linehan and the food she prepares each day.

*

Let me be clear that Joanne Linehan’s culinary repertoire includes more than just sourdough bread. Hunters and anglers from across the globe relish a return to her table for meals of bear roast and root veg braised in wine, elk loin grilled rare and pink beneath a blackened crust of herbs, grouse soup that could warm the dead. Her chocolate-chip cookies with a hint of coarse salt are dream-worthy, and her shrimp and grits, served under an umbrella of summer stars, would make a southern man cry. Don’t get me started on her service in the name of wild mushrooms...

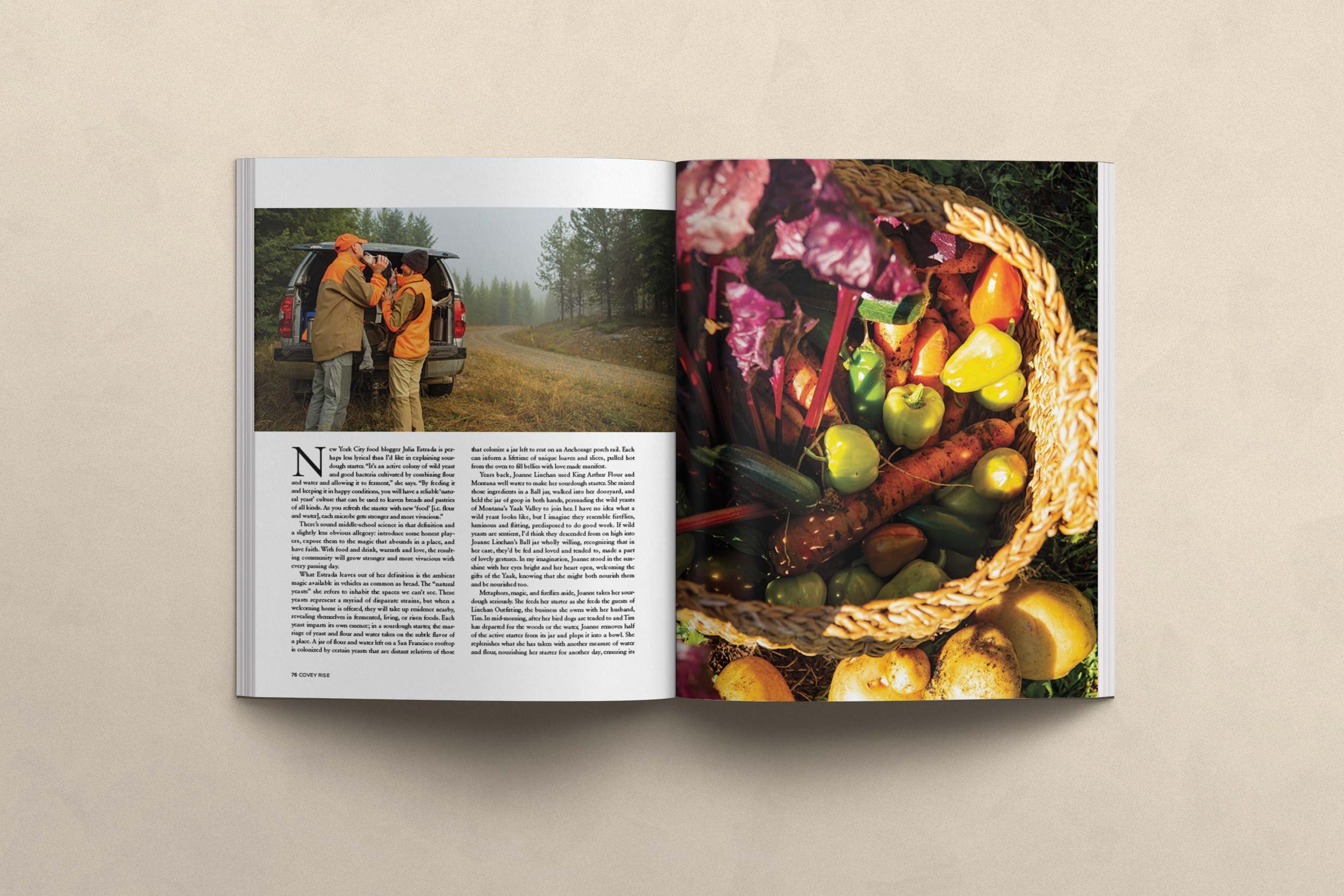

She uses ingredients more prosaic too, things like pork medallions and grass-fed steaks, but the through-line in Joanne’s cooking is a commitment to food sourced fresh and locally, wild where possible, and delivered with unabashed love. This philosophy is her bedrock. “Food is not a means to an end; it’s a fueling and nurturing of our bodies. It should be fresh, made from scratch, healthy, pretty… a combination of textures and colors. And it should express the flavor of its place. Living like we do, I became much more grounded eating locally and seasonally. That is where I have arrived. Everything that I can harvest and touch, that is what I want to eat, and what I want to feed the people at my table.”

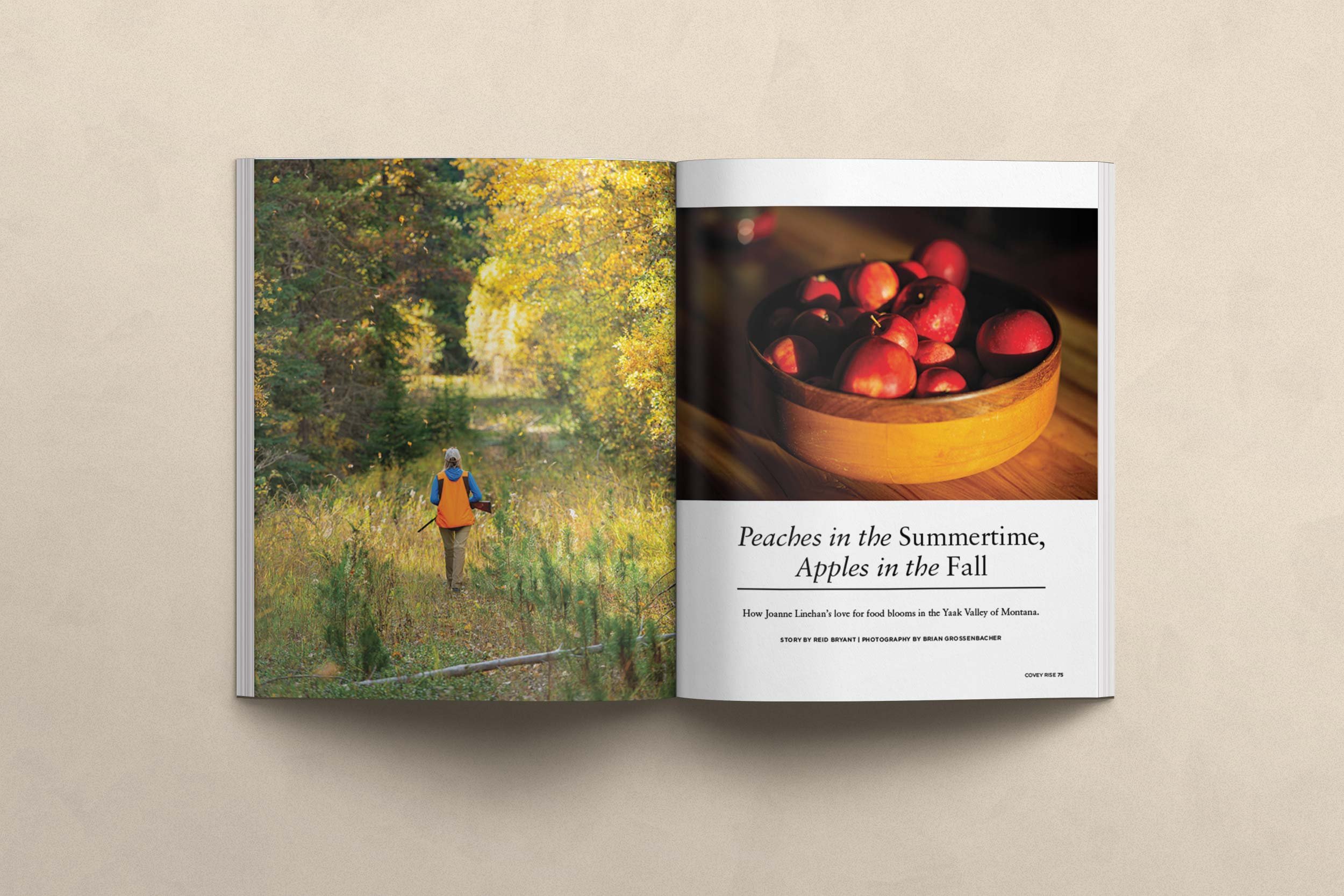

Montana’s Yaak valley is an untamed place. Grizzlies and wolves wander just inside the tree lines, and people maintain a frontier independence. It can be a hard place to eke out a living. Nonetheless, those inclined towards abundance will find it in the Yaak. Among the days that encompass a year in northwest Montana, sustenance comes in increments, each mouthful linked to season and to landscape, to snowmelt and bird migrations, to the waxing and waning of the days. Each piece of food has a point of intersection: there are grouse in the gone-to-gold aspens, elk interrupted in their autumnal passage from the valley floor to the ridgetops, huckleberries stolen from bears in summer brush, morel mushrooms hunted like easter eggs in May’s glorious emergence. There are whitetails shot in the high, dark timber, or just off the roadside when opportunity knocks. The dedicated few spade a garden out of the tree shadows and realize that bounty too: tomatoes and hearty brassicas in the swollen summer, sweet peas and baby greens too eager to last past June. These things punctuate the year and give it flavor, wild and domestic. At any given moment, Joanne Linehan may well be incapable of telling you the exact date, but she will accurately tell you what is heavy with winter fat, or just gone by, or just budding out and extending first leaves. She will acknowledge such matters in her kitchen and share them at her table. This intimacy with food and place was not achieved overnight. Joanne’s immersion, like all good things, took some time to mellow and mature.

Joanne met Tim Linehan in New Hampshire after college, and the two dated for a few years. She was building a tidy life teaching pre-school and kindergarten, working in a ski and bike shop, catering, and settling into her own house. Tim was in sales, and not terribly happy about it. He was an outdoor guy, a ski racer and soccer player, and a lifelong sportsman. In the years that he and Joanne dated in New Hampshire, he would drive up towards the Canadian border on weekends to guide fly anglers on the region’s storied trout streams. That was what he loved, and soon enough he saw that he needed to give the guide’s life a serious look. Early in ’89 he loaded his truck and set out for a season in Montana.

The relationship between Joanne and Tim was a bit precarious that winter, as Joanne remained at home in New England, and Tim took on a pre-fishing season caretaking gig in the Yaak (notably filling in for the writer Rick Bass who was off to Texas for a semester teaching English). Tim was tasked with the care of the Fix Ranch, a sprawling, off-the-grid property a few miles from the Yaak’s public phone and mercantile, and over the dark, cold, weeks of winter he and Joanne exchanged letters. It was unclear what the future would hold, but the bond between Tim and Joanne only strengthened with miles, and the Yaak had a magnetism that was hard to quantify. Joanne visited for a week that February and moved out west for good the following September. “I was seriously in love with Tim,” she recalls. “I left everything back east, and I set out on this big adventure; neither one of us had any idea what the end game looked like. We figured we’d live out there for a while, then go back to New Hampshire.” Thirty-some years later, they haven’t left Montana.

Tim’s original plan to leave the Yaak Valley to guide in Twin Bridges fell apart as guide gigs can, but lower down the Yaak Valley a local couple named Bill and Judy McAfee were operating a sporting Lodge. Tim signed on as fishing guide and would proceed to help build that business. Rick Bass returned to the Fix Ranch to resume his writing and caretaking, and Joanne and Tim moved into new digs at a remote cabin known as the Vinal Lake House. They made do as only young optimists can, scraping out a meager living, eating fish and game and beans, relying on a pull-start generator for running water, using their one vehicle to make the fourteen-mile round trip to use the phone or get the mail. Judy McAfee, co-owner with husband Bill of the Lodge where Tim worked, coaxed from Tim the admission that his young girlfriend up the valley was filling her lonesome days with long walks to the mailbox and tinkerings with the generator. Judy came by the Vinal Lake House one day, scooped up Joanne, and took her to work at the Lodge, specifically in the kitchen. Joanne had catered and worked in kitchens back east, and she knew the drill, but Judy was a phenomenal mentor. In her kitchen, Joanne learned the organizational skills required of a Lodge chef, the finer points of ordering and budgeting and feeding hungry sportsmen. Judy and her family also modeled to the young couple the subtle art of living in rural community, helping neighbors and sharing resources, being there with a cold beer or a warm wood stove or a hug.

Tim worked for McAfee’s for three years as a guide in both fishing and hunting seasons, helping out with admin, maintenance, and marketing around the edges. After the three years of guiding required by the Montana Board of Outfitters, he got his own outfitting license in 1992, and started selling his own guided trips, albeit without lodging. Joanne cobbled together jobs to support, teaching in the Yaak’s one-room school, selling real-estate, and cooking. As Linehan Outfitting built a client base and filled a calendar, the remoteness of the location begged Joanne and Tim to establish more infrastructure. In 1998 they set to work building guest cabins on a piece of property they purchased high up the valley, and Joanne went to work for the business full-time. In 2000 the Linehan’s acquired a river house in nearby Libby that would allow more summer fishing clients to stay right on the banks of the Kootenai River, and they shifted Linehan Outfitting into a more comprehensive guiding/lodging/hospitality model. And of course, the hungry sportsmen and women needed to eat.

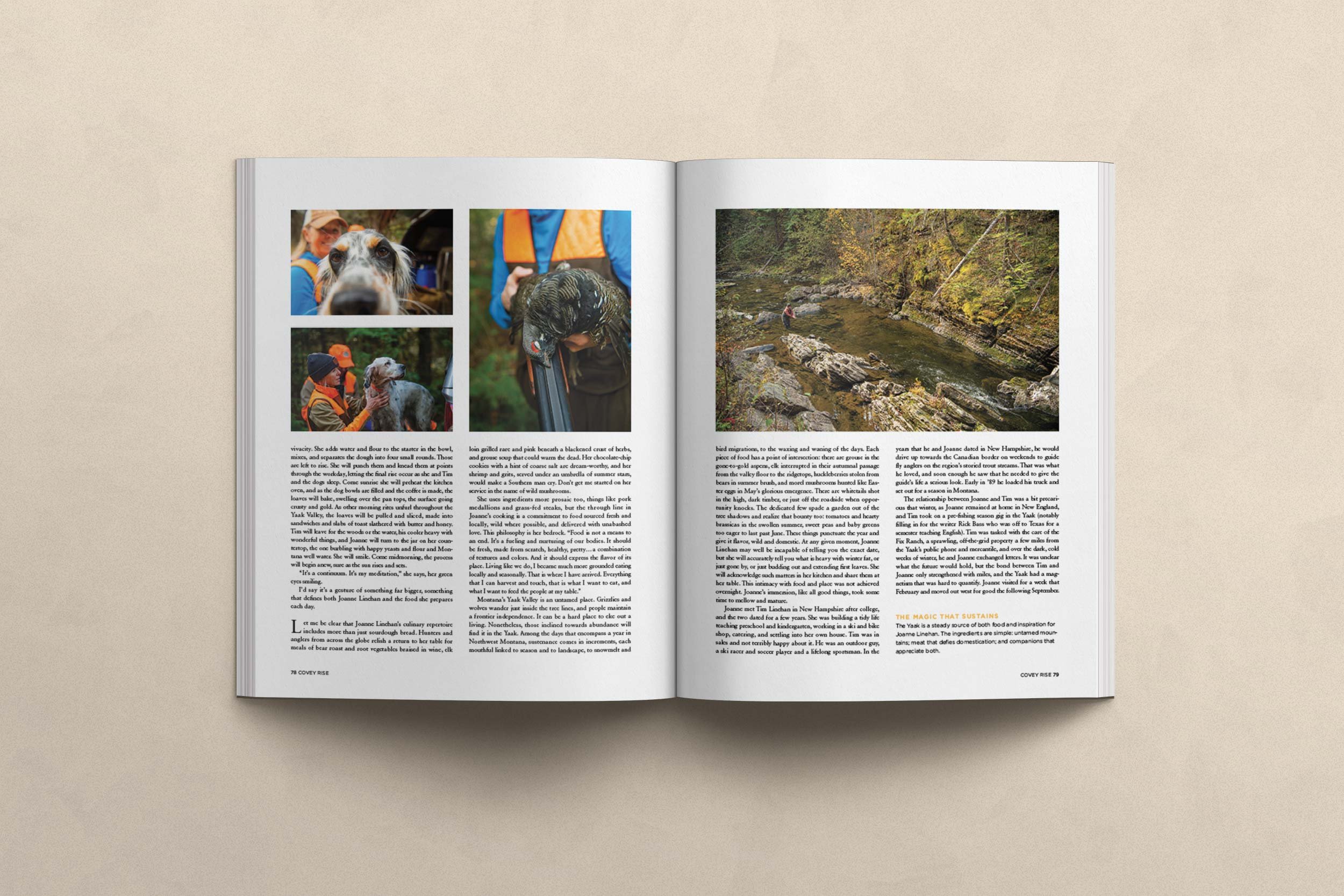

Since 2000, Joanne Linehan has cooked breakfast, lunch, and dinner for the guests at the river house throughout the summer fishing season, prepping meals in her home kitchen and making the drive from the Yaak to Libby each day to finish, serve, and host. She preps breakfasts and shore lunches ahead of time, and in the windows of the workday that allow, she tends her garden and shops at the local farmer’s market. In the hunting seasons of fall and winter she provides baked goods and soup for guests at the Yaak Valley cabins, and field lunches that are so refined and delightful they’d be appropriately served with a chilled Sancerre and a red-checked tablecloth on the truck tailgate (not really, but almost). Also in the fall, winter, and spring, Joanne hunts and gathers. She drifts through the dark timber with a rifle and sits on deer trails. She carries a 20-bore Sauer on her dog walks. She helps Tim break down and process bear, moose, and mountain lion. She picks mushrooms and wild berries by the pail-full, and she fills her freezer in anticipation of the guest’s arrival. Her procurement is as much an act of love as her preparation. “Lion poppers, spruce grouse, venison shanks… I always try to feed our guests something they haven’t had before. I won’t shoot an animal if we don’t need the meat, but we usually need the meat. I love to serve game.” And of course, there is always the bread.

*

“I think my relationship with food is a creative outlet. I went to school to learn to be creative and playful. Remember, I was trained to be a preschool teacher.” Joanne’s eyes are laughing again, and her delicate hands are at work. Tim is watching the Red Sox on the television, and the Grateful Dead are again providing the score for the Linehan’s descent into an autumn evening. Dinner is in the making. A quartet of bird dogs are sprawled on the couch and armchairs. Outside, southbound geese are plaintive. “The kitchen is my sanity, my place to create.” Joanne retrieves a jar of dried morels from the cupboard.

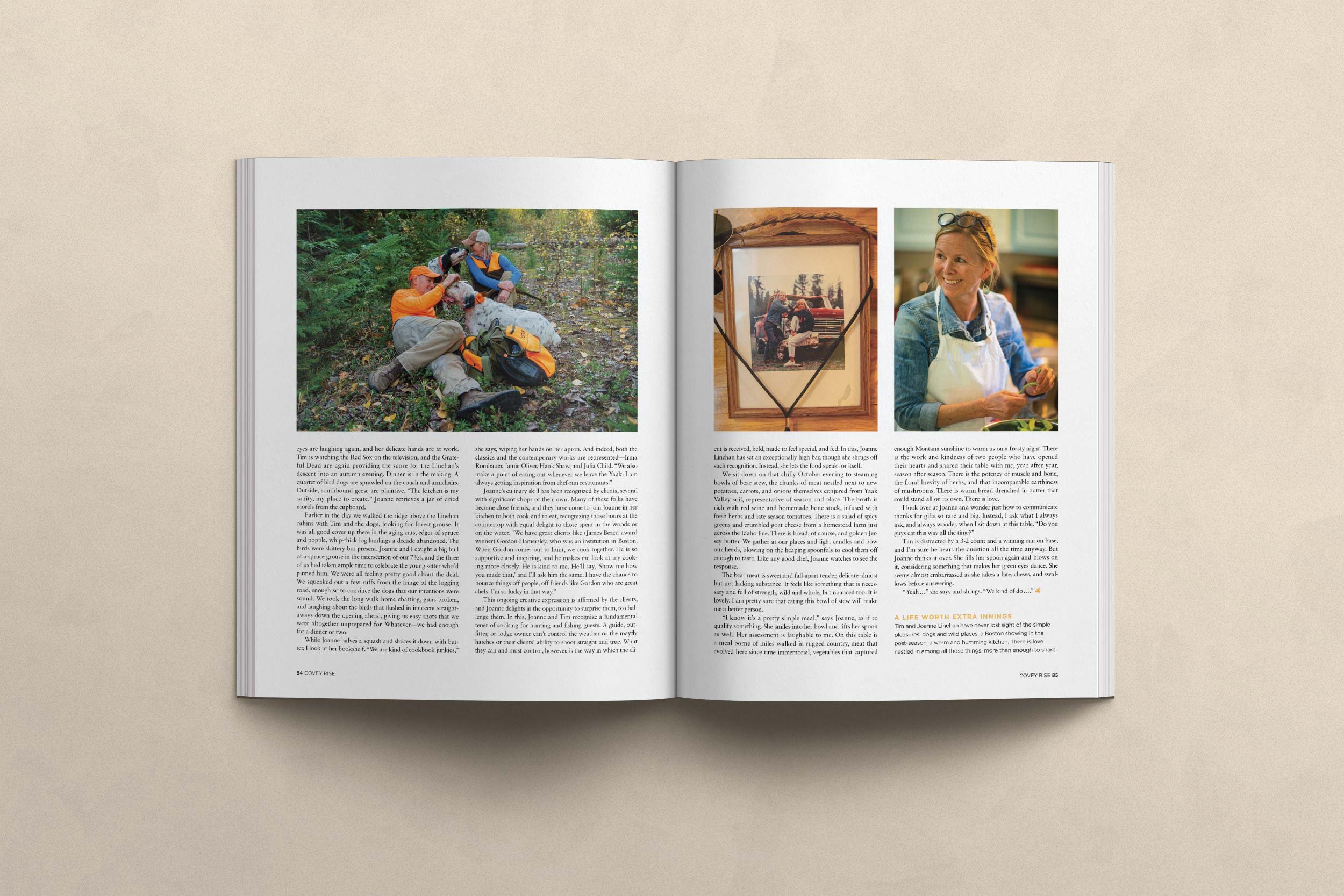

Earlier in the day we walked the ridge above the Linehan cabins with Tim and the dogs, looking for forest grouse. It was all good cover up there in the aging cuts, edges of spruce and popple, whip-thick log landings a decade abandoned. The birds were skittery but present. Joanne and I caught a big bull of a spruce grouse in the intersection of our 7 ½’s, and the three of us had taken ample time to celebrate the young setter who’d pinned him. We were all feeling pretty good about the deal. We squeaked out a few ruffs from the fringe of the logging road, enough so to convince the dogs that our intentions were sound. We took the long walk home chatting, guns broken, and we laughed about the birds that flushed in innocent straightaways down the opening ahead, giving us easy shots that we were altogether unprepared for. Whatever… we had enough for a dinner or two.

While Joanne halves a squash and sluices it down with butter, I look at her bookshelf. “We are kind of cookbook junkies,” she says, wiping her hands on her apron. And indeed, both the classics and the contemporary works are represented – Irma Rombauer, Jamie Oliver, Hank Shaw, Julia Child. “We also make a point of eating out whenever we leave the Yaak. I am always getting inspiration from chef-run restaurants.”

Joanne’s culinary skill has been recognized by clients, several with significant chops of their own. Many of these folks have become close friends, and they have come to join Joanne in her kitchen to both cook and to eat, recognizing those hours at the countertop with equal delight to those spent in the woods or on the water. Says Joanne “we have great clients like (James Beard award-winner) Gordon Hammersley, who was an institution in Boston. When Gordon comes out to bird hunt we cook together. He is so supportive and inspiring, and he makes me look at my cooking more closely. He is kind to me. He’ll say ‘show me how you made that’, and I’ll ask him the same. I have the chance to bounce things off people, off friends like Gordon who are great chefs. I’m so lucky in that way.”

This ongoing creative expression is affirmed by the clients, and Joanne delights in the opportunity to surprise them, to challenge them. In this, Joanne and Tim recognize a fundamental tenet of cooking for hunting and fishing guests. A guide, outfitter, or Lodge owner can’t control the weather, or the mayfly hatches, or their clients’ ability to shoot straight and true. What they can and must control, however, is the way in which the client is received, held, made to feel special, and fed. In this, Joanne Linehan has set an exceptionally high bar, though she shrugs off such recognition. Instead, she lets the food speak for itself.

We sit down on that chilly October evening to steaming bowls of bear stew, the chunks of meat nestled next to new potatoes, carrots, and onions themselves conjured from Yaak Valley soil, representative of season and place. The broth is rich with red wine and homemade bone stock, infused with fresh herbs and late-season tomatoes. There is a salad of spicy greens and crumbled goat cheese from a homestead farm just across the Idaho line. There is bread of course, and golden Jersey butter. We gather at our places and light candles and bow our heads, blowing on the heaping spoonfuls to cool them off enough to taste. Like any good chef, Joanne watches to see the response.

The bear meat is sweet and fall-apart tender, delicate almost but not lacking confidence. It feels like something that is necessary and full of strength, wild and whole but nuanced too. It is lovely. I am pretty sure that eating this bowl of stew will make me a better person.

“I know it’s a pretty simple meal…” says Joanne as if to qualify something. She smiles into her bowl and lifts her spoon as well. Her assessment is laughable to me. On this table is a meal borne of miles walked in rugged country, meat that evolved here since time immemorial, vegetables that captured enough Montana sunshine to warm us on a frosty night. There is the work and kindness of two people who have opened their hearts and shared their table with me, year after year, season after season. There is the potency of muscle and bone, the floral brevity of herbs, that incomparable earthiness of mushrooms. There is warm bread drenched in butter that could stand all on its own. There is love.

I look over at Joanne and wonder just how to communicate thanks for gifts so rare and big. Instead, I ask what I always ask, and always wonder, when I sit down at this table. “Do you guys eat this way all the time?”

Tim is distracted by a 3-2 count and a winning run on-base, and I’m sure he hears the question all the time anyway. But Joanne thinks it over. She fills her spoon again and blows on it, considering something that makes her green eyes dance. She seems almost embarrassed as she takes a bite, chews, and swallows before answering.

“Yeah…” she says and shrugs. “We kind of do…”

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine