Instagrouse

There is nothing quite as lovely as a north woods autumn, when the world goes crystalline beneath the year’s first frost, and October moons push timberdoodles into the lowlands south. It is then that the aspens turn from green to gold to naked silver, and the thornapples shine red against the bone of coming winter. The year’s young partridge sift into tangled corners from which they thunder out, thrilling us with sparest glimpses: hatchet heads and barred tails bending, fleeting apparitions punctuated by #8 shot. These days of concerted beauty tempt the north woods hunter into the brambles once more, entangling his hat and shirt-sleeves for too few days, while gripping his soul for a lifetime. Ruffed grouse and woodcock, orchard walls and popple whips, wobbly Parker guns and sickle-tailed setters… these are the things that afford substance and identity, well beyond the scope of a bulging and blood-stained bag.

Looking back over a half lifetime in the north woods, what captivates me most is the aesthetic. At the core of my delight are the birds themselves, which are lovely without ostentation, a melody of color both drab and dizzyingly intricate. Their peculiarities are fascinating too: birds that fly by moon-shadow, that skitter through the thorned and thankless understory, that elude advancing footfalls in their flushes, only to confound me one time in a hundred with the blessing of a straightaway shot. I am captivated by what frames these creatures: a landscape flaming out in a burst of color, fading all too fast to ashen gray. And I love that all of this has been cherished, chewed on, and summarized by a legacy of men that navigated the seasons and tromped through an evolving landscape behind a bloodline of dogs purpose-built. These men emerged from towns where cows were milked and lumber was sawn and socks were darned by pragmatic hands, and import was given to grace. It goes without saying that grace was said for birds and dogs and seasons, and it was reflected in their art and poetry.

No other genus of hunting has been celebrated such. No other genus of hunting can claim the likes of a William Harnden Foster, a Burton Spiller, a George Bird Evans, a Tap Tapply, an Aldo Leopold… men given to harnessing moments in ink and watercolor and well-ordered words, toasting it all with a belt of bourbon. That grouse and woodcock inspired their moments and aroused their expression, makes absolute sense to me; I know the coals that glow in the north woods hunter’s heart. I know the full-heart feeling of a ‘little russet feller’ heavy in the hand, when the world smells like rotting apples and sweat has soaked a wool collar clean through.But in our lexicon, these men and their expressions have become retrospectives of a bygone era. In some ways, we north woods hunters relish the Wharton-esque grimness of our heritage, commenting aloud that the golden days have come and gone. Indeed, the abandoned farms of Spiller’s Maine are, in large part, now grown over, and the Pinetop grouse of Tap and Gorham are both rare and reluctant to sit tight for a dog. As in grouse and woodcock hunting, those people and those places that defined the passing autumns scab over and mature and eventually go dormant, as they have since time began. They do not offer what they once did, and for that we postulate that the good ‘ole days are gone.

In recent years, having listened hard to my elders as I was taught to do, I’ve considered somewhat quietly that we north woods hunters might be served better to broaden our collective faith. After all, the grouse and woodcock that eluded Foster’s gun didn’t up and disappear, though they likely nudged their progeny out of pre-war Andover and into places more hospitable. And so it goes that if the grace is imbued with a dollop of hope, we might see instead a renaissance in place, a golden age of artistry and poetry, settling gently all about us, like popple leaves on fertile soils. There must be a metaphor here somewhere.*Envision a man pushing 40, with just enough gray in his beard to give him an air of competence. He runs three setters rich with Ryman blood, and smokes sweet black Cavendish from a full-bent briar. In the crook of his arm is a twenty-bore Parker with the case colors worn, and his brush pants are frayed at the cuffs. Through the autumn afternoons he walks the hardwood edges south of Lake Huron, stopping at day’s end to drink bourbon on the tailgate and listen to the ‘doodles spill in. He’s known as an artist of some repute, and a hand at spinning yarns. He has rows of leather-bound volumes on his library shelves, and in his woodshed a brace of still-limp biddies hangs by a cord.

This man, Jason Dowd, could have stumbled clear out of Foster’s New England, or into Evans’ Pennsylvania. But unlike those men, his landscape is a contemporary one, and he walks through woods that have come and gone, come and gone, and grown up once again since the supposed golden days of grouse and woodcock. His aesthetic bridges a generation gap with reverence. He’s a student of the past in a vital and consummate present, walking a northern forest awash in birch whips, birds, and burgeoning autumn. Jay lives in Flint Michigan and he hunts the forests around Meredith. He writes and draws and muses, composing stories of his days afield in still-life, in photo, in pen and ink. He has tattoos on his knuckles and on the backs of is hands, and he spends a bit of each week with his aging grandpa, who taught him to love a landscape. Perhaps he’s a relic of a bygone era; perhaps he’s a reluctant seer of what’s to come.

You may know Jay Dowd not by his given name, but by his handle, Upland Lowlife. Under this moniker, Jay embarked several years ago on a social media campaign, using Facebook and Instagram to share his memories, just as Gorham Cross and Ogden Pleissner used paper and paint. With digital means Jay harnessed his moments and shared them, as much for his own enjoyment as for the gratification of fellow upland gunners. He is unapologetic about the modern day, choosing instead to inhabit it; a timeless crescent of autumn reverberates out over digital channels, available at once to a world of rapidly-digesting viewers.

At first, this outlet was primarily a way for Jay to record his days afield. But Jay, making use of the media he had at hand, stumbled into two sociological phenomena: first, he saw that people wanted to share his autumns, living vicariously in his present, one salted heavily with the past. Second, there grew a collective awareness of other folks equally as passionate, and as reverent, hunting and writing and painting and drawing and similarly channeling it across social media. Digital outlets shed fluorescent light into the shadowy corners, illuminating a fraternity that had been there all along. What Cross and Tapply and Spiller formed through shared geography, word of mouth, and print, Jay Dowd and his brethren formed through tweets and messages and hash-tags. Different vehicles, different times… but in the end a communion of sentiment.*I met Jay Dowd at his grouse camp, in the woods below Lake Huron. The invitation was an obscure one: a mutual hunting buddy had been following Jason’s moments on Instagram, and had likewise been following his pals: Northwoods’R (aka Garret Mikrut and Nick Larsen), Northbound Gundogs (aka Matt Mates), The Royal Flush (aka Sam Glasbergem), Project Upland (A.J. DeRosa). By virtue of what they were sharing, it looked like these guys were students of the past, ardent stewards of the future, and fellows with a respectful but whimsical take on contemporary upland hunting. My buddy and I ventured west to find them in their element, and see their aesthetic in motion.

Camp was a small square house with all lights lit and a yard-fire smoldering under a drizzly Michigan night. The boys were gathered around the table eating goose sausage and telling stories. They welcomed us with Stroh’s and whiskey, and not the slightest question of our belonging there. It seemed that we were welcomed into their order: cans, bottles, and broken-down guns were swept aside to make room at the table. I couldn’t help but see, when the fridge was cracked for another round, that the crisper shelves were stacked with birds, fully feathered and mellowing beside the groceries. We were rolled into the jokes at once, and the re-telling of the day’s events.

We moved outside as the night grew long, and stood around the fire. Garret and Jay lit pipes, Nick and Matt lit clandestine cigarettes, and Sam dodged barbed allusions to a certain grouse dispatched hours earlier from a tree limb (for shame). Jay laid out the plan for the days to come. In short, we’d hunt from dawn till dark, running the collection of dogs which were crated in every corner of the camp. We’d roam the country around Merediths and converge when we got hungry for a tailgate lunch of sausages and cheese and apples. At dark we’d return to camp and toast the day and feed the dogs, and undoubtedly tell each other our lies. The days to follow would do so in kind.

We slept cheek-by-jowl on the floor of the camp, with setters filling the gaps between our sleeping bags. At sunup Jay stirred and made coffee, and Garrett, his hair spiky and his beard unkempt, stumbled out to test its mettle. The two went outside to smoke pipes and breast out the previous day’s woodcock. I felt it my duty to start the bacon. The rest of the boys rolled out in dribs and drabs; more coffee was made, and some blood-red scallops of meat were fried in bacon grease, and we ate bacon, egg, and woodcock sandwiches for breakfast. Duly fortified for a day afield, we assembled guns and dogs and hitched up our suspenders, and warmed the trucks while the coffee pot was emptied into thermoses.

Out in the field we spread out in pairs and threes, finding favorite coverts and hunting partners organically, largely based on who wanted to see whose dog run. Double guns were lovingly assembled and handed around for inspection. There were Foxes and Parkers and Winchesters and Webleys, none of them hugely fancy, all of them brush-battered and honestly used. Many of them were of a vintage twice that of the oldest member of our crew, who incidentally had managed a whopping 40 years. Phones came out and photos were taken unobtrusively of dogs and pipe smoke, aspen leaves and bird tracks in the mud… the commonest sights so rarely given notice. We spilled out into the coverts and followed dogs into Hemingway country, looking and feeling much as he must have, so many years before.*As I get older, I am increasingly aware of my own tendency to rely on my nostalgia. As my kids grow bigger and my hair gets thin, life’s passage becomes all too fleeting, compounding the more immediate passages of seasons and of days. I suppose this is a natural part of growing older, cresting the hill and gathering momentum downwards, while the times that have passed become more distant and a bit less clear. Maybe this is why we cling to those golden years, those glowing moments, as if compensating for their outlines growing indistinct. Oh that we could instead see that the best is all around us, perhaps the best that’s ever been.

I like to think that I don’t malign my love for grouse and woodcock hunting with that all-too-common assertion that ‘it ain’t like it used to be’. I like to think I don’t have those curmudgeonly thoughts about the youth of today and their impatience, their detachment, their fascination with a digital reality, or lack of reality at all. I like to think that the north woods hunter of today will cultivate the reverence and the language, the warm tones of Spiller and Leopold and Foster, but I may be deluding myself. In the popple whips of Michigan, however, I saw men cut from better cloth.

The last bird I saw Jay shoot was a female woodcock that we’d somehow missed, not thirty yards from the truck. We’d parked along an access road beside a played out oil well that heaved creakily along, whunking away at nothing. His top dog Ruthie had made a good run, and the middle girl Georgie had kept right up, and we all saw the truck and the promise of some water and a rest on the tailgate. Georgie gamely made one last cast into a spear point of aspens and the bell stopped short. In the green and the shadows all I could see was a bloodstained tail tip high and straight, and sliver of white flecked black. Jay called the point, quietly positioned me outside, and lurched into the pecker-poles to flush. I can still see him there: a bearded man in glasses and suspenders, mud-splattered boots and a threadbare plaid shirt, a faded orange cap slightly cockeyed on his head. He soothed the dog and walked ahead of her, his little Parker pointing skyward. He stomped in a circle and scanned the ground, as I stood ready to do my part. Nothing rose. He released the dog. She didn’t budge. He looked out at me as if to call it off and a little wedge of autumn broke free and tinkled out through the whips to my right, into space I could hear but not see. I watched Jay pivot then, shoulder a generations-old gun in a generations-old posture of sound intention. The gun spoke and the dog broke and the cut aspen leaves, now golden, sifted gently to the ground. No piece of the tableau would have been out of place in a George Bird Evans painting, and no gunner of that era would have been more proud of a white setter dog politely depositing a ‘doodle into the master’s hand.

At day’s end we sat and drank beer, and Jay petted his dogs, who flopped beside the truck, tongues lolling. Jay spoke about his young daughter and his grandpa and his pen-and-ink commissions of game birds in flight. He talked about making a go of his art full-time, his early successes in publishing tales of his hunting in several of the upland gunning journals. He spoke of the season still to come, and the friends he’d made through his online presence, friends who were just then emerging from adjacent coverts just down the gravel track. He spoke about how with social media, he’s been able to record moments just like the one at hand, for himself and his daughter and anyone else who cared see, which it turned out numbered quite a few. It all seemed to mystify him a bit, in the way good artists always seem a bit mystified by their success.

I wonder if perhaps, nearly a century ago, Tap Tapply, Gorham Cross, and Burton Spiller ever shared a parallel moment. Dogs exhausted, guns broken, a little bit of strong stuff in a tin cup on the running board. Maybe they told stories liberally salted down with idiom of their own – The Old Master and Grandpa Grouse, marveling over a p’atridge or two if the day was good. I wonder too if they, like their contemporary Upland Lowlife, were simply blessed to know, beyond a doubt, that the best days are here right now. Maybe what makes the north woods hunter whole is the conviction that this is the golden age of grouse and woodcock, and that should indeed be celebrated, by whatever expression lies near at hand.

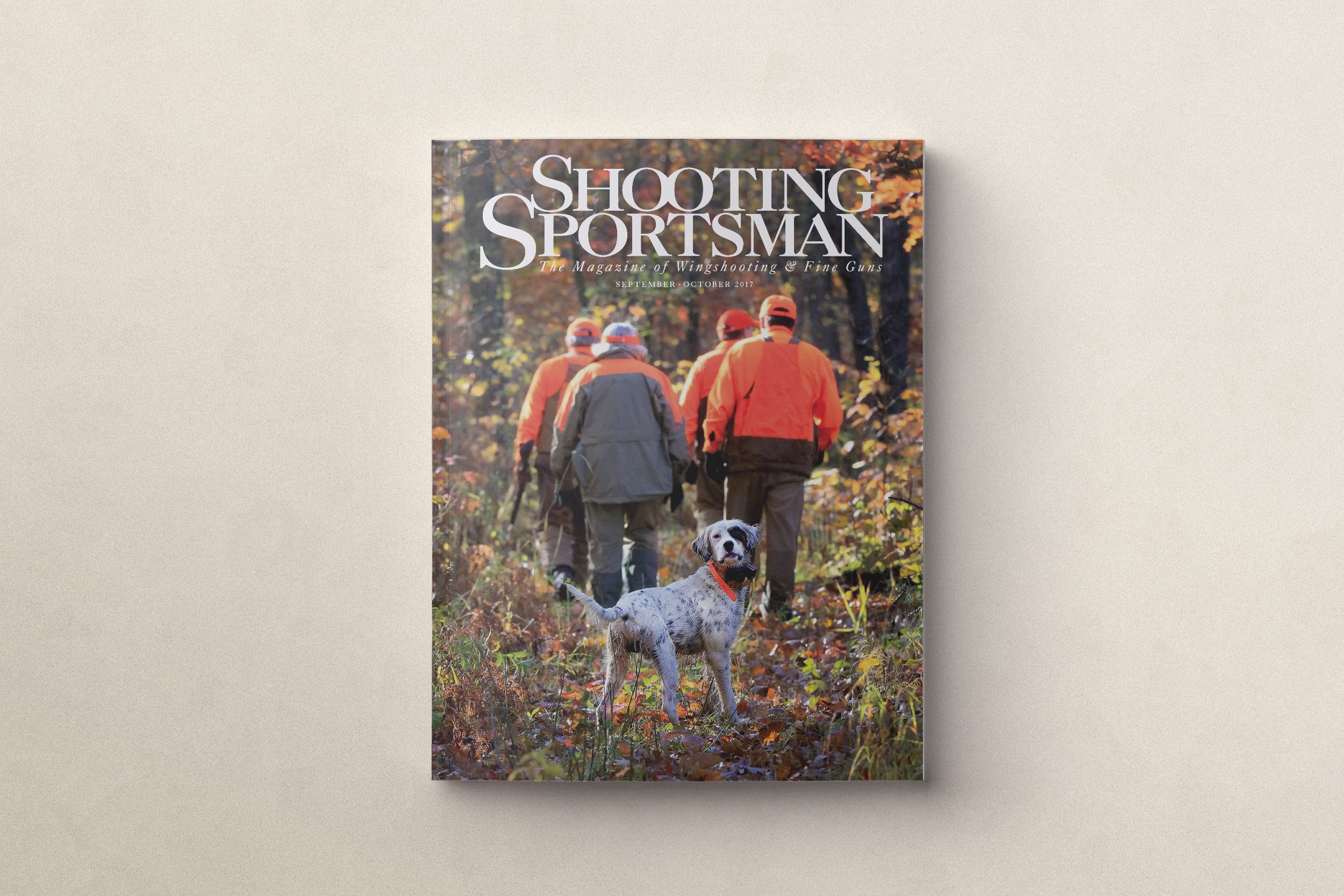

First published Shooting Sportsman Magazine September/October 2017