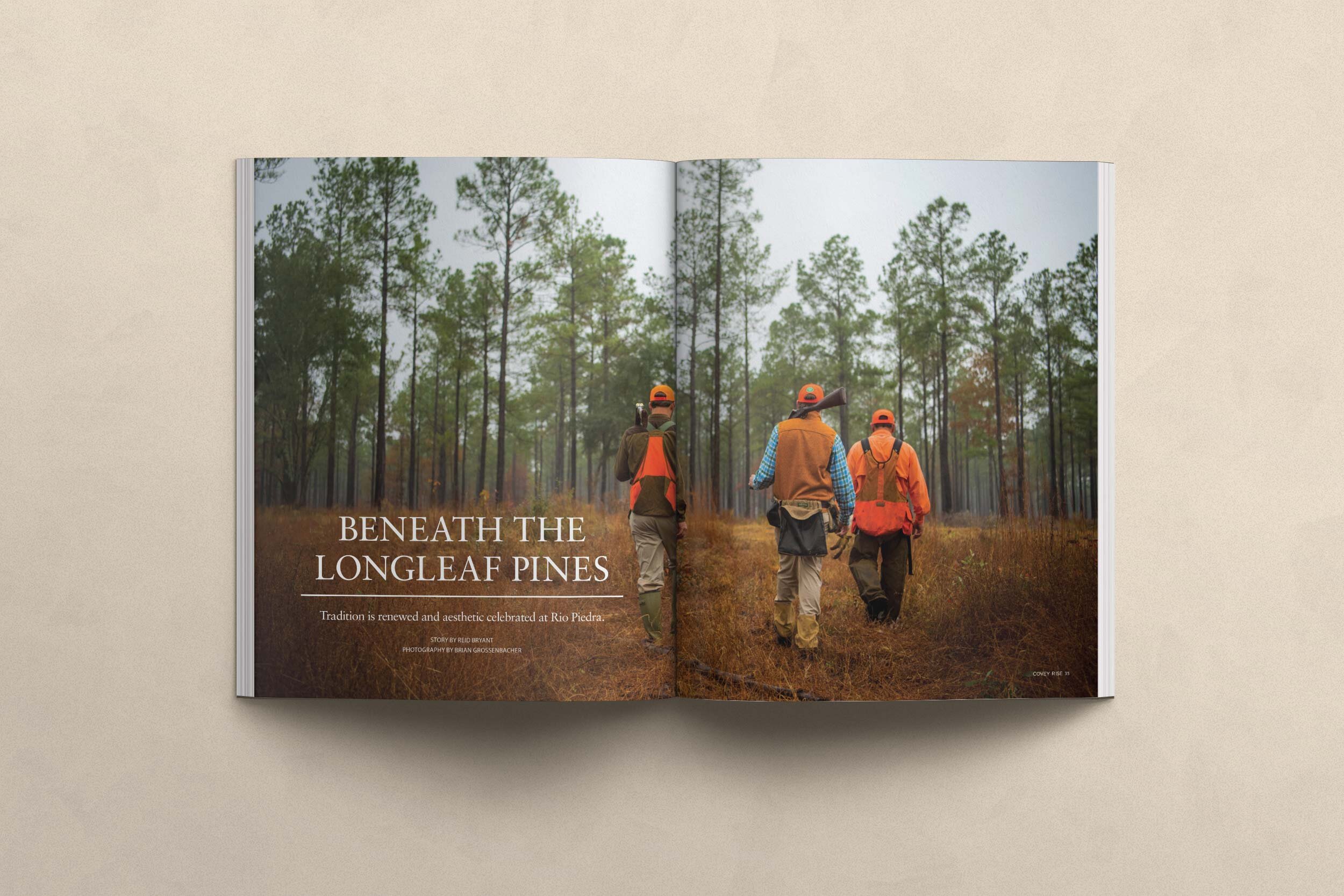

Beneath the Longleaf Pines

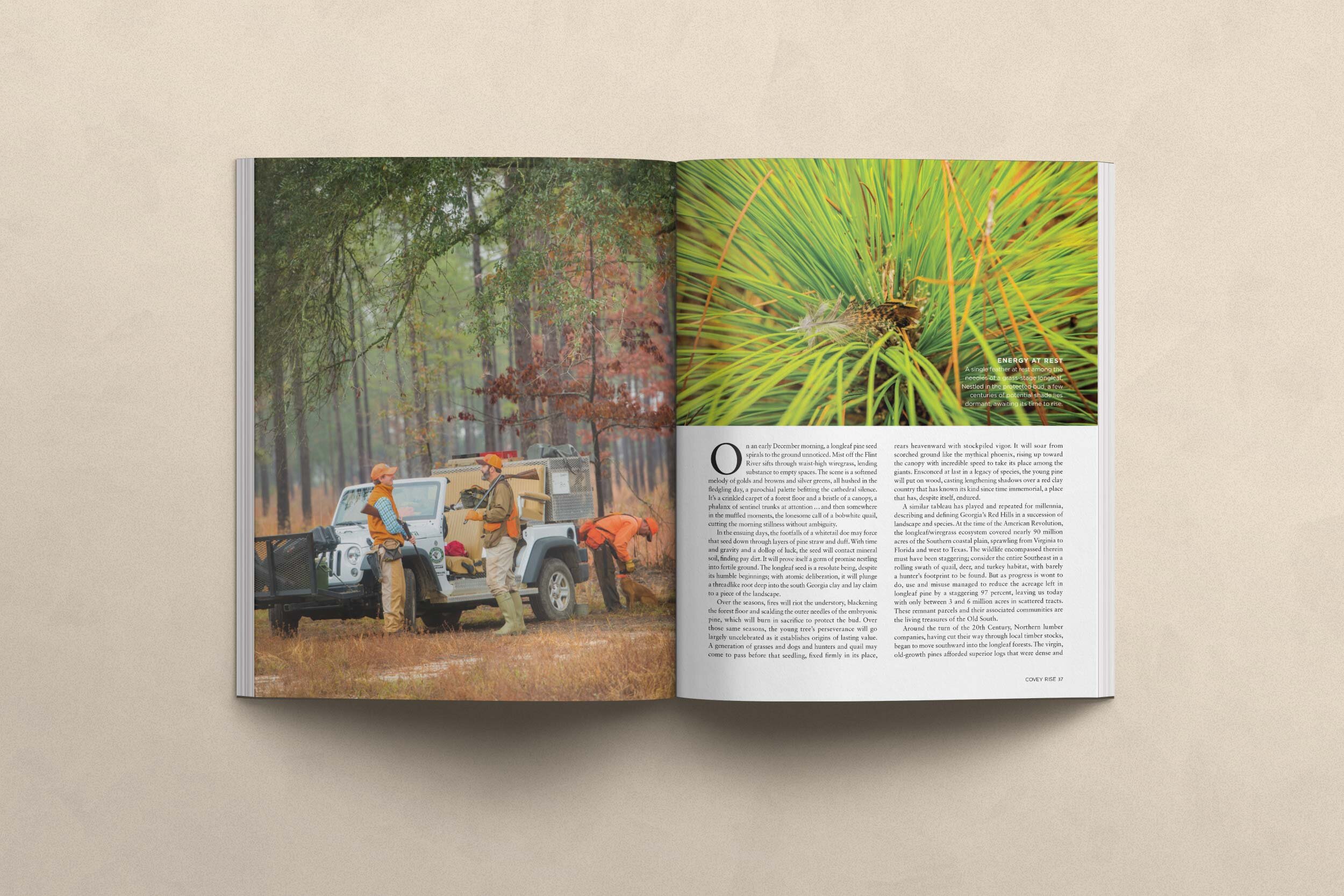

On a December morning, a longleaf pine seed spirals to the ground unnoticed. Mist off the Flint River sifts through waist-high wiregrass, lending substance to empty spaces. The scene is a softened melody of golds and browns and silver greens, all hushed in the fledgling day, a parochial palette befitting the cathedral silence. It’s a crinkled carpet of a forest floor and a bristle of a canopy, a phalanx of sentinel trunks… and then somewhere in the muffled moments, a lonesome covey call, cutting the morning stillness without ambiguity.

In the ensuing days, the footfalls of a whitetail doe may force that seed down through layers of pine-straw and duff. With time and gravity and a dollop of luck, the seed will contact mineral soil, finding paydirt. It will prove itself a germ of promise nestling into fertile ground. The longleaf seed is a resolute being, despite its humble beginnings; with atomic deliberation, it will plunge a threadlike root deep into the south Georgia soil, and lay claim to a piece of the landscape.

Over the seasons, fires will riot the understory, blackening the forest floor and scalding the outer needles of the embryonic pine, which will burn in sacrifice to protect the bud. Over those same seasons, the young tree’s perseverance will go largely uncelebrated, as it establishes origins of lasting value. A generation of grasses and dogs and bobwhite quail may come to pass before that seedling, fixed firmly in its place, rears heavenward with stockpiled vigor. It will soar from scorched ground like the mythical phoenix, rising up towards the canopy with incredible speed to take its place among the giants. Instated at last in a legacy of species, the young pine will put on wood, casting lengthening shadows over a red-clay country that has known its kind since time immemorial, a place that has, despite itself, endured.

A similar tableau has played and repeated for millennia, describing and defining Georgia’s coastal plain in a succession of landscape and species. At the time of the American Revolution, the longleaf/wiregrass ecosystem covered nearly 90 million acres of the southern coastal plain, sprawling from Virginia to Florida and west to Texas. The wildlife encompassed therein must have been staggering; consider the entire southeast in a rolling swath of quail, deer, and turkey habitat, with barely a hunter’s footprint to be found. But as progress is wont to do, use and misuse managed to reduce the acreage left in longleaf pine by a staggering 97%, leaving us today with only between 3 and 6 million acres in scattered tracts. These remnant parcels and their associated communities are the living treasures of the old South.

*

Around the turn of the twentieth century, northern lumber companies, having cut their way through local timber stocks, began to move southward into the longleaf forests. The virgin, old-growth pines afforded superior logs that were dense and straight. As the cutting inched deeper inland, the railroads followed, exchanging a wealth of lumber for a stream of labor, back and forth to the northern tier. The availability of newly timbered land made way for rough agriculture as well, as farmers from the coast occupied inland Georgia with patchwork subsistence farms.

By the 1920’s, timbering within the longleaf/wiregrass ecosystem had resulted in a devastation of species on a scale similar to that seen in the contemporary Amazon. Nonetheless, in south Georgia there arose an incidental positive: fragmented tracts of forest interlaced with hodge-podge farms had in fact concentrated and nourished local quail populations. On these broken pieces beneath the residual longleafs wild coveys bloomed and divided, much to the delight of the Yankee sportsmen who’d coincidentally encountered a similar potential in the rolling hills around Thomasville.

Riding the rail line to its southern terminus from Cleveland and New York, early industrialists found fresh air and winter reprieve in the Red Hills, as well as an under-tapped resource in the native quail. With disposable income and a desire to establish significant hunting opportunities in perpetuity, the first of the hunting plantations were established, collected loosely in what is now known as the ‘plantation belt’. Pebble Hill, Chinquapin, Longpine, Sinkola… the hallowed names persist in lands that have been handed down through generations. The plantation culture, the bobwhite quail, and the timeless elegance of pointing dogs and double guns might well be the symbiotic salvation of the longleaf pine ecosystem, wherein all four thrive; it’s no doubt the love for the aforementioned elements that has kept what remains of their southern range intact.

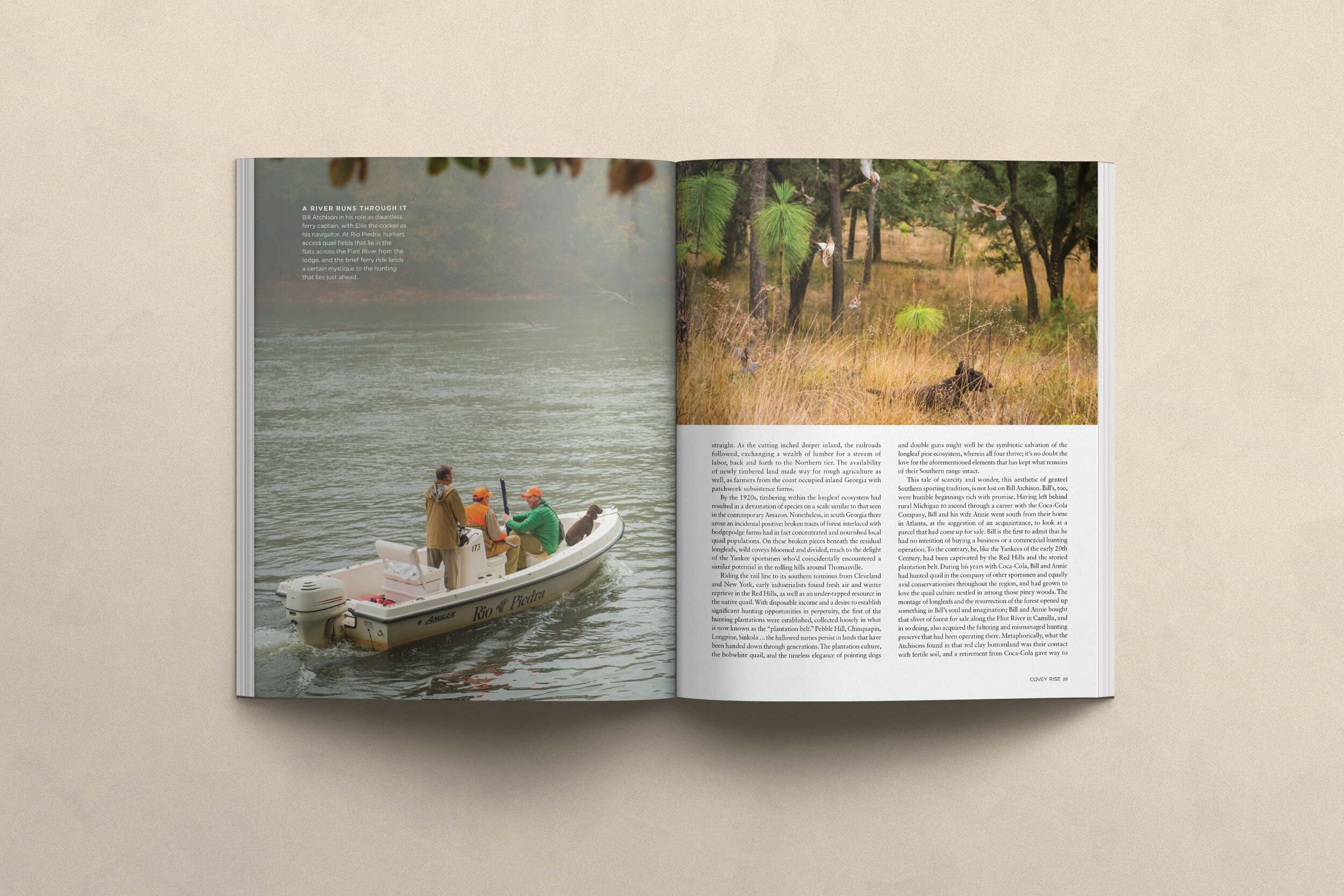

This tale of scarcity and wonder, this aesthetic of genteel southern sporting tradition, is not lost on Bill Atchison. Bill’s too were humble beginnings rich with promise. Having left behind rural Michigan to ascend through a career with the Coca-Cola Company, Bill and his wife Annie went south from their home in Atlanta at the suggestion of an acquaintance, to look at a parcel that had come up for sale. Bill is the first to admit that he had no intention of buying a business or a commercial hunting property. To the contrary, he, like the Yankees of the early twentieth century, had been captivated by the Red Hills and the storied plantation belt. During his years with Coca-Cola, Bill and Annie had hunted quail in the company of other sportsmen and equally avid conservationists throughout the region, and had grown to love the quail culture nestled in amongst those piney woods. The montage of longleafs and the resurrection of the forest opened up something in Bill’s soul and imagination; Bill and Annie bought that sliver of forest for sale along the Flint River in Camilla, and so doing also acquired the modest hunting preserve that had been operating there. Metaphorically, what the Atchisons found in that sandy bottomland was their contact with fertile soil, and a retirement from Coca-Cola gave way to a re-birth of purpose. After a few years laying down roots, Bill and Annie leaned into the project of resurrecting an entrenched and refined regional sporting culture on a pine-strewn wedge of hunting ground along the Flint River. Under the watchful gaze of the longleafs, their vision took flight. Today, they perpetuate the halcyon days of southern quail with the full aesthetic intact, giving hunters the world over a place and an experience known as Rio Piedra Plantation.

*

On a misty December morning, Bill Atchison shuttles me and a small group of hunters across the Flint River, and leads us deeper into his sliver of that residual longleaf forest. The mists and the silences abound, and somewhere in the mix, the longleaf seeds are no doubt falling, though the morning’s focus is on matters slightly more evident. With a box full of whining bird dogs and a brace of double guns assembled, we the hunters are here for quail. As the hunting jeep stops and the world re-collects itself, a bobwhite covey calls, and injects focus into a December morning.

With two pointers down and an English cocker at heel, we set out into the day. Rio Piedra has grown in the years since Bill and Annie first purchased a piece of the Red Hills, and now encompasses nearly 6000 acres of prime quail habitat. But radiating out in every direction from the forest where Bill and I walk is that fabled plantation belt, and the largest remaining contiguous, or near-contiguous tract of longleaf/wiregrass forest to be found on private land. Covering a wide swath of south Georgia and north Florida, the plantation belt now describes a network of nearly 100 private plantations owned and managed foremost for wild bobwhite quail hunting. These properties are enjoyed by owners and guests on a highly restricted basis, as they have been for generations. Scarcity of birds and habitat, and the incredible resource demands involved in perpetuating both, cultivate an inherent exclusivity; very few folk can hunt the elegant Georgia longleafs for hard-flushing wild bobs, in the genteel image of presidents and nobles, movie stars and magnates.

Certainly, put-and-take preserves make quail hunting available to the general public, but the old-world charm and elegance of the iconic plantation hunt is often missing, as is the opportunity to see honest-to-goodness wild birds in their native range. Rio Piedra’s geography, however, makes for a unique opportunity. Bill and Annie instituted a land management plan following the guidelines set forth by Tall Timbers Research Station, and introduced a protocol of seasonal burning, timber harvesting, supplemental feeding, and planting parallel to that encountered on the adjacent private properties. The demands of commercial hunting necessitated supplemental stocks of introduced quail, but the unbroken cover and prevalence of wild birds on contiguous properties fosters the potential for wild birds to sift into Rio Piedra hunting courses unimpeded. Quail, ignorant of man-made boundaries, see ground as ground and cover as cover, and Rio hunters are therefore in a position to encounter birds that are the true natives of the old south. That Rio Piedra makes the elegance and tradition of southern quail accessible to all is a testament to Bill and Annie’s inherent generosity, their love for this place and its history.

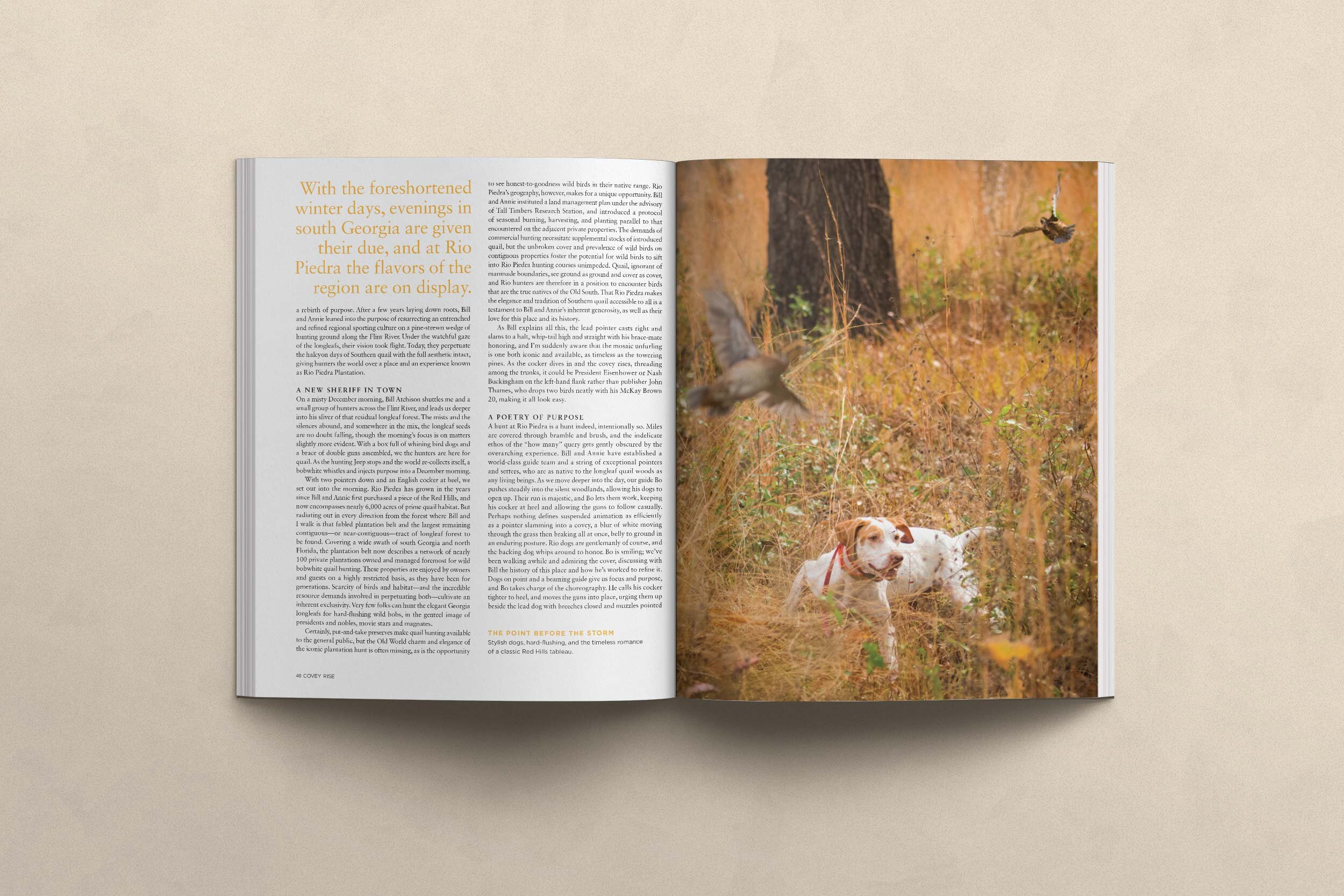

As Bill explains all of this, the lead pointer casts right and slams to a halt, whip-tail high and straight with his brace-mate honoring, and I’m suddenly aware that the mosaic unfurling is one both iconic and available, as timeless as the towering pines. As the cocker dives in and the covey rises, threading among the trunks, it could be President Eisenhauer or Nash Buckingham on the left-hand flank rather than publisher John Thames, who drops two birds neatly with his McKay Brown 28, making it all look easy.

*

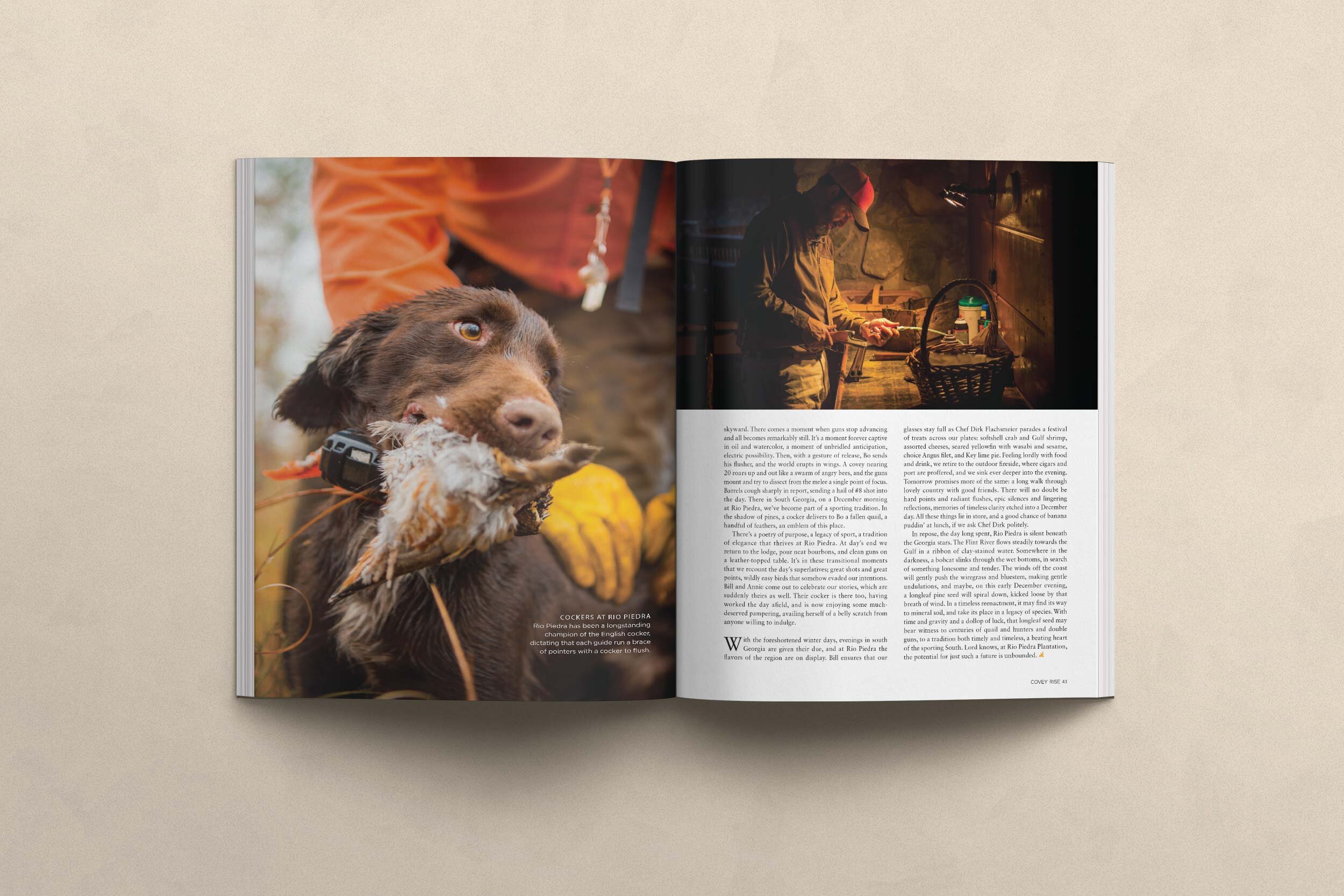

A hunt at Rio Piedra is a hunt indeed, intentionally so. Miles are covered through bramble and brush, and the indelicate ethos of the ‘how many’ query gets gently obscured by the overarching experience. Bill and Annie have established a world-class guide team and a string of exceptional pointers and setters, who are as native to the longleaf quail woods as any living beings. As we moved deeper into the day, our guide Bo pushes steadily into the silent woodlands, allowing his dogs to open up. Their run is majestic, and Bo lets them work, keeping his cocker at heel and allowing the guns to follow casually. Perhaps nothing defines suspended animation as efficiently as a pointer slamming into a covey, a blur of white moving through the grass then braking all at once, belly-to-ground in an enduring posture. Rio dogs are gentlemanly of course, and the backing dog whips around to honor. Bo is smiling; we’ve been walking awhile and admiring the cover, discussing with Bill the history of this place and how he’s worked to refine it. Dogs on point and a beaming guide give us focus and purpose, and Bo takes charge of the choreography. He calls his cocker tighter to heel, and moves the guns into place, urging them up beside the lead dog with breeches closed and muzzles pointed skyward. John is on the left and Mary Katherine on the right, and there comes a moment when guns stop advancing and all becomes remarkably still. It’s a moment forever captive in oil and watercolor, a moment of unbridled anticipation, electric possibility. Then, with a gesture of release, Bo sends his flusher, and the world erupts in wings. A covey nearing twenty roars up and out like a swarm of angry bees, and the guns mount and try to dissect from the melee a single point of focus. Barrels cough sharply in report, sending a hail of number 8 shot into the day, and Mary Katherine, swinging her Merkel through a crosser, dumps the bird neatly into the grass. There in South Georgia, on a December morning at Rio Piedra, we’ve become part of a sporting tradition. In the shadow of pines, a cocker delivers Bo a limp little body, a handful of feathers, an emblem of this place.

*

There’s a poetry of purpose, a legacy of sport, a tradition of elegance that thrives at Rio Piedra. At day’s end we return to the Lodge and pour neat bourbons, and clean guns on a leather-topped table. It’s in these transitional moments that we recount the day’s superlatives; great shots and great points, and those wildly easy birds that somehow evaded our intentions. Bill and Annie come out to celebrate our stories, which are suddenly theirs as well. Their cocker Ellie is there too, having worked the day afield, and is now enjoying some much deserved pampering, availing herself to a belly scratch from anyone willing to indulge.

With the foreshortened winter days, evenings in south Georgia are given their due, and at Rio Piedra the flavors of the region are on display. Bill ensures that our glasses stay full as Chef Dirk Flachsmeier parades a festival of treats across our plates: softshell crab and gulf shrimp, assorted cheeses, seared yellowfin with wasabi and sesame, choice Angus filet, key lime pie. Feeling lordly with food and drink, we retire to the outdoor fireside, where cigars and port are proffered, and we sink ever deeper into the evening. Tomorrow promises more of the same: a long walk through lovely country with good friends. There will no doubt be hard points and radiant flushes, epic silences and lingering reflections, memories of timeless clarity etched into a December day. All of these things lie in store, and a good chance of banana puddin’ at lunch, if we ask chef Dirk politely…

*

In repose, the day long spent, Rio Piedra is silent beneath the Georgia stars. The Flint River flows steadily towards the gulf in a ribbon of acid-stained water. Somewhere in the darkness, a bobcat links through the wet bottoms, in search of something lonesome and tender. The winds off the coast will gently push the wiregrass and bluestem, making gentle undulations, and maybe, on this early December evening, a longleaf pine seed will spiral down, kicked loose by that breath of wind. In a timeless re-enactment, it may find its way to mineral soil, and take its place in a legacy of species. With time and gravity and a dollop of luck, that longleaf seed may bear witness to centuries of quail and hunters and double guns, to a tradition both timely and timeless, a beating heart of the sporting south. Lord knows, at Rio Piedra Plantation, the potential for just such a future is unbounded.

First Published in Covey Rise