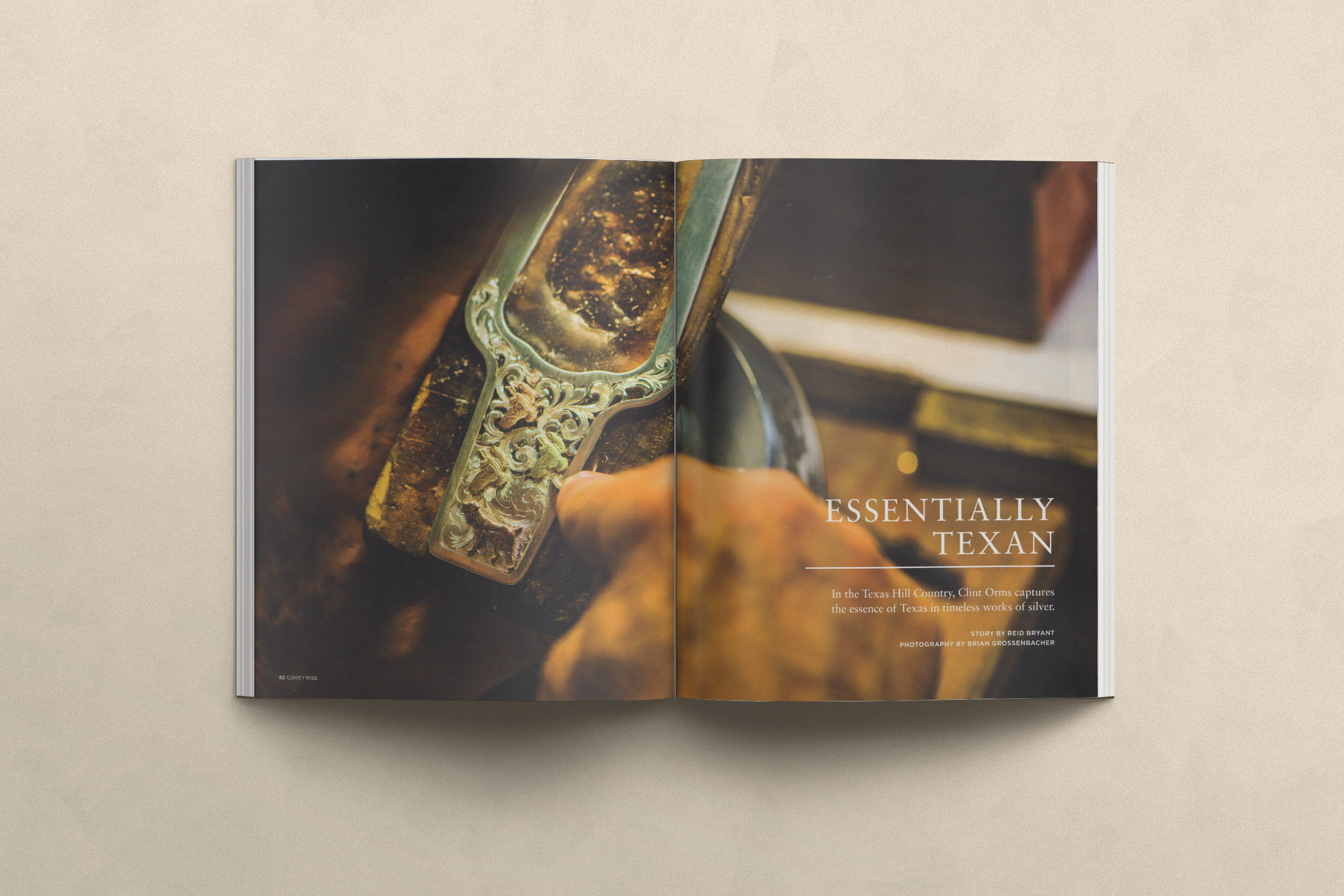

Essentially Texan

When you travel through Texas you occasionally gain a bit of elevation that distinguishes the region and your place within it. Cresting a rise, you look out across a sweep of brush and country and see that space as the sum of its parts: cattle fences and cedar breaks, a bleached and broke-down goat shed, hard sun and big silences. It is a challenge, in the scope of such a spectacle, not to feel a little bit small, even a little bit lonesome. It is also hard not to think that other folks have passed that way before and framed themselves against the same piece of land and sky, but in a context that made the view somehow even bigger, and a bit more lonesome, than the one you’d see today.

Only a few short generations ago, Texas was a land of cattle drivers, horse rustlers, Commanche warriors, and mesquite. It was also a land of opportunity and freedom that exacted a toll from those who made a life upon it. What livelihood was possible, before the oil boom at least, came through livestock and agriculture, and the back-breaking work of making both produce something of value in that sharp, rough country. Such work required men and women who were rawhide-tough, given to lifetimes spent stringing fence and moving cattle, and sleeping night after night in the rattlesnake desert beneath the Texas stars.

It’s no wonder that the icon of the Texas cowboy has such a lasting potency. After all, the cowboy is a person whittled down to the barest essence, an emblem of frontier grit that is softened only by a twinge of philosophical leaning. A cowboy’s work required long miles in the saddle in all manner of weather; he was a man who cozied up with danger and boredom, hunger and cold, and immeasurable hours of loneliness. Yet something in that life, and the stuff that compelled it, remains quite beautiful, even aspirational. Perhaps it is just that a cowboy appreciated a job hard-earned and well-done, valued the leanness of a life without superfluity, maintained an uncluttered pride in calloused hands and a bone-tired feeling at day’s end. But so too, in the context of that lean hard life, did the beautiful things, things like pride of place and work and self-identity, became all the more valuable. Cowboys were, and likely remain, unabashedly proud and not a little romantic. When given the opportunity they lavish that pride on tokens of beauty and worth, things like fine hats and pearl-handled Colts and silver buckles. This too is logical. After all, in the misery of a Texas winter’s rainstorm, a cowboy could find some sovereignty in just holding a little something pretty in his hand.

*

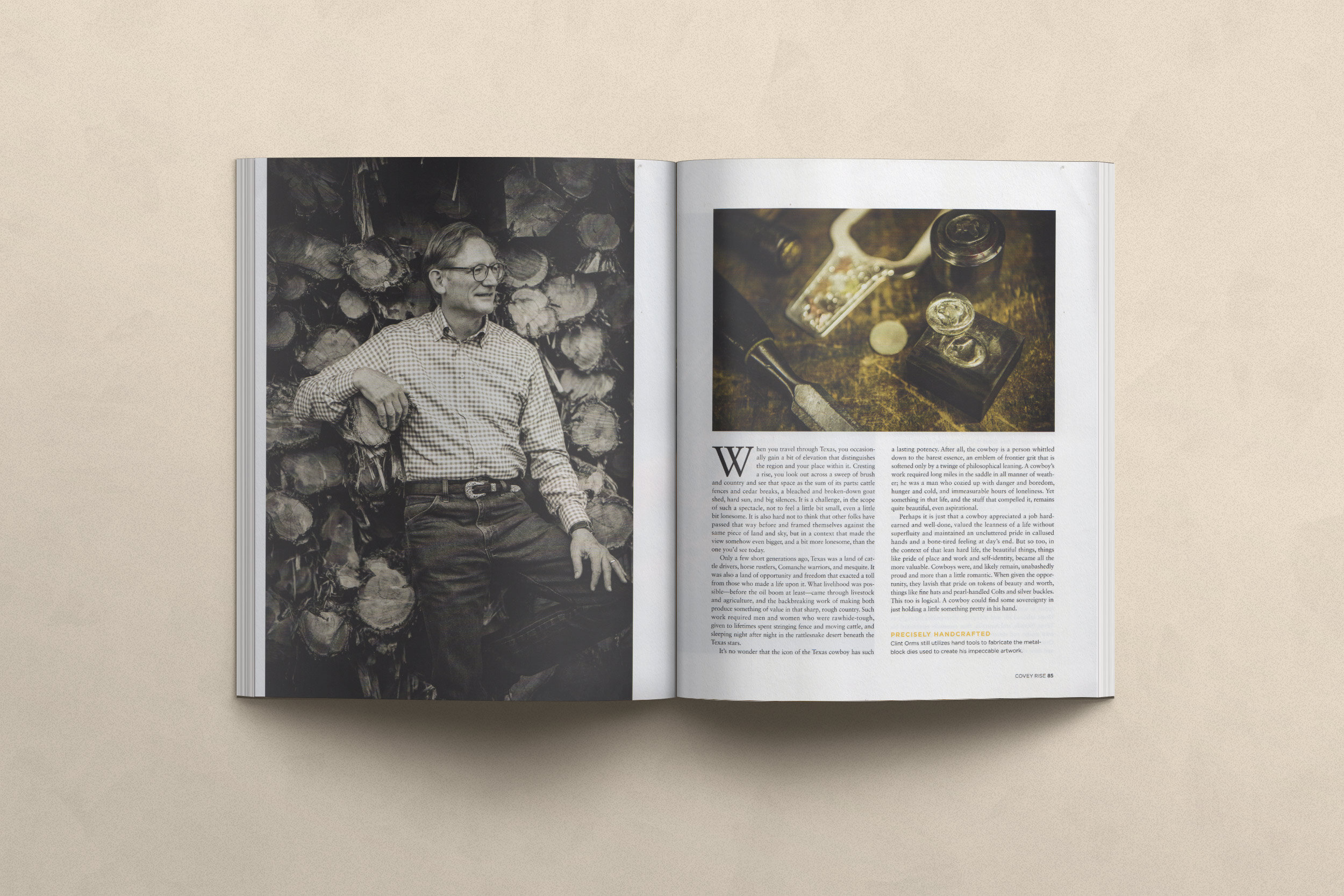

Clint Orms, who owns and operates Clint Orms Engravers and Silversmiths in Ingram, Texas, knows a thing or two about the grit and romance emblematic of cowboy culture. “When I was a kid, I wanted to be a champion cowboy,” he said as we sat in a café overlooking the Guadalupe River. “I grew up in Wichita Falls in north Texas, in cowboy country. My dad got us into rodeo as kids. Rodeo-ing taught me a lot about passion and determination. If you are going to stay on the back of a bull for 8 seconds, you have to fight for it all the way.”

Orms quietly inhabits the notion that things of worth don’t come easy, and don’t come fast. Though he determined early on that a career as a rodeo champion was not in his stars, he no less knew that the cowboy ethos had impressed upon him some lasting lessons. “I like that about the cowboy image, the idea of putting in a sixteen-hour day on horseback, dawn till dark. Those guys aren’t afraid to work. They appreciate grit, and they appreciate effort, both the effort required in the work they do, and the effort that goes into any job done well.” Orms also came from a family that valued craft. “My dad was a western clothing salesman, and my grandmother was a western seamstress. They put value on quality work. When I was thirteen I started my first company, making and selling tooled leather belts. I grew up in a setting where someone was always making something with their hands.”

Grit, passion, and determination seem to be recurring themes in Clint’s life, themes that were to steer him away from leatherwork into the world of decorative silversmithing. As a teenager Orms noted that leather belts, though beautiful, lacked the longevity of decorative metal. Moreover, he recognized that within that iconic cowboy culture, treasures and trophies were singular. Belt buckles in particular were prized and were historically made to be passed down. The idea that a cowboy might have that one item of lasting value to commemorate an event or affirm an identity made sense to Orms, and he was increasingly disheartened to see that cheap, outsized buckles were becoming common rodeo trophies and fashion pieces through the 70’s and 80’s. He aimed to bring back something of multi-generational meaning to quantify the cowboy ideal and preserve a piece of western heritage. At sixteen, Orms followed a family friend to Albuquerque to get a crash course in silver-working. From there, he leaned into the craft with the dedication and passion that had kept him on the back of bulls and broncs, and he embarked on a professional career as a silversmith.

Over the past four decades, Clint Orms has worked tirelessly and thoughtfully to differentiate himself as an artisan. After high school, he packed up his car and moved to California to work for a silversmith there. For the next twenty years, Orms labored for and alongside silversmiths throughout Texas, Nevada, and Australia, then eventually established his own studio and storefront. With signature diligence, Clint Orms never deviated from his commitment to a job done well and done right; in turn he has become widely heralded as the finest western silversmith of the modern era. His work is so iconic, and in such high demand, that a certain cultish status has been afforded the ownership of an original Orms piece. His engraved buckles and money clips have been purchased by and for royals, dignitaries, and heads-of-state; there are those among the social elite of Texas who maintain that an Orms buckle is absolutely de rigeur when dressing formally, or informally, for any noteworthy function. A beloved Wyoming silversmith recently said of Orms “Clint has done us all a favor. He’s proven that our work is of value, and what we produce is valuable… and it should be treated as such.” Owning a piece of silver work by Clint Orms has become, somehow, the same as owning a sliver of something essentially of Texas. And like most things essentially of Texas, each Orms piece is destined to become both an object of fierce pride and the recipient of unabashed, and unwavering, veneration. And yet, when stripped of all the circumstance, there are those modern-day cowboys who, in the rain-soaked misery of a winter’s storm, still find some warmth and strength and beauty in the piece of Clint Orms silver on their belts.

*

After lunch, I followed Orms back to his studio, turning south off Highway 39 onto The Old Ingram Loop. Ingram, Texas, is a Hill Country town above the Guadalupe River that would be altogether recognizable to the hardscrabble cowboys of yore. The Loop follows the old road into the heart of Ingram, a road lined with stuccoed store fronts and low-slung shade porches. There is a gnarled and ancient hanging tree across the road from Orms’ shop, a linking Ingram back in living tissue to its frontier roots. I followed Orms into the building that was once the town hospital but now houses his retail space and studio. I found myself taken by the vitality, the creative hum, of the place. The front showroom, which features antique glass cases full of Orms’ silver work, felt like something from a bygone era. Museum-quality metalwork sit on velvet pads behind rippled glass, and row upon row of belts crafted from exotic leathers hang on pegs behind the cases. There is a colossal and seemingly ancient steel safe in one corner, some hides and decorative leather draped over chairs, and framed accolades and western art on the walls. But just beyond the storefront, the working lifeblood of the Orms studio is both visible and audible. Through an open door, Orms’ team of silversmiths and engravers bend over their benches, making modern-day treasures in a time-honored tradition.

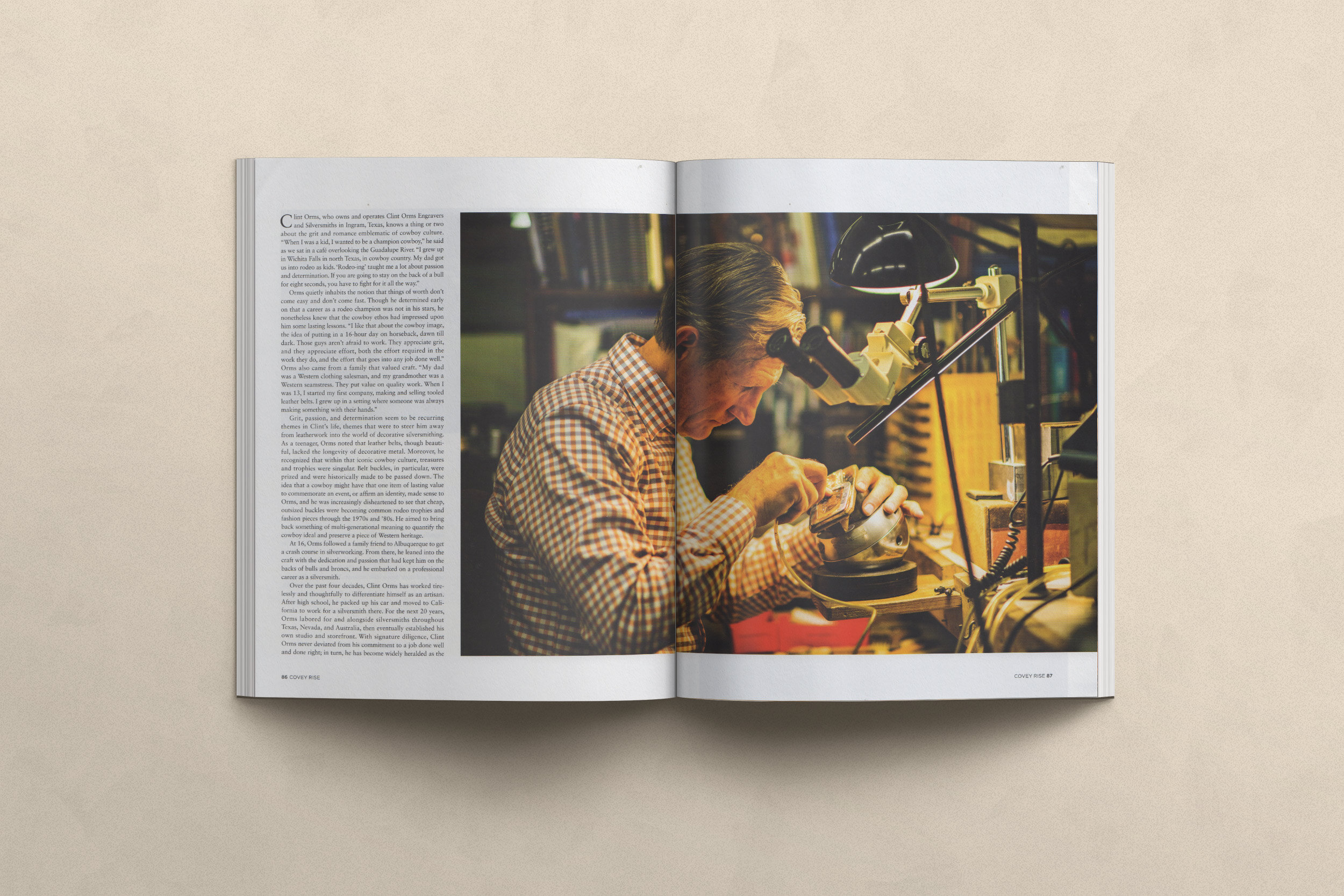

I followed Orms through the shop for that afternoon, learning the process by which his craft takes shape, and the nuances that make a Clint Orms piece so exquisite, and so unique. “We don’t try to make things cheaper and faster,” said Orms, taking the blank sprung silver of a money clip back to the braising room. “We want to make things that are world-class. I want every piece to wind up in Christie’s Auction House in fifty years.” The folks working in the Clint Orms shop seem to share this philosophy, and each member of the team has a certain skill-set that is leveraged to maximum effect. There are specialist engravers and folks designing buckles, a skilled hand or two working up concepts in modeling clay. There is a convivial vibe across the benches; soft country music plays, and bottles of cold Big Red are popped and shared. “Luckily I have a team here that wants to work together,” said Orms, swapping work stations with a fellow engraver. “The harder the job we are tasked with, the more fun it is to accomplish.”

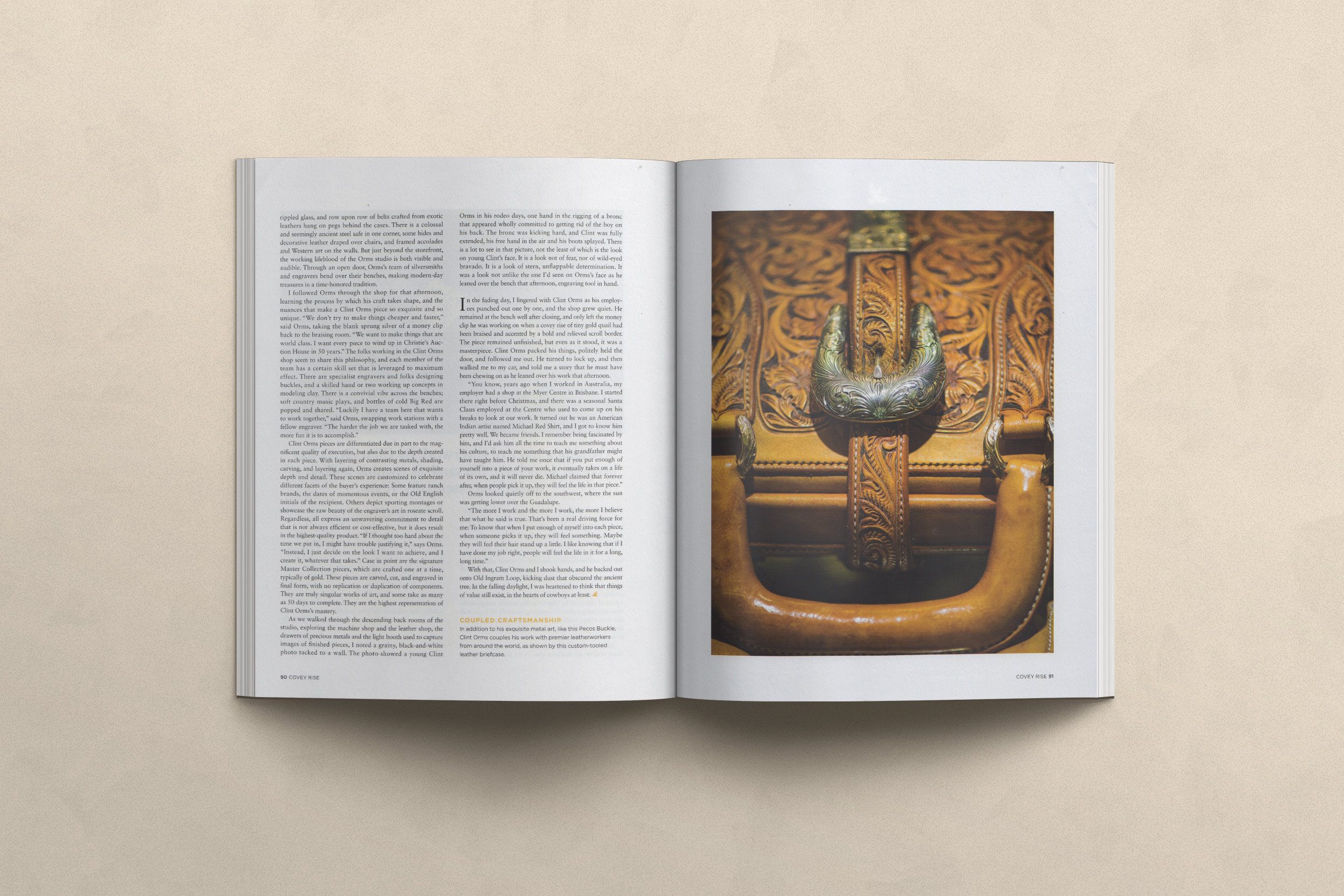

Clint Orms pieces are differentiated due in part to the magnificent quality of execution, but also due to the depth created in each piece. With layering of contrasting metals, shading, carving, and layering again, Orms creates scenes of exquisite depth and detail. These scenes are customized to celebrate different facets of the buyer’s experience: some feature ranch brands, the dates of momentous events, or the old-English initials of the recipient. Others depict sporting montages or showcase the raw beauty of the engraver’s art in roseate scroll. Regardless, all express an unwavering commitment to detail that is not always efficient or cost-effective, but it does result in the highest quality product. “If I thought too hard about the time we put in, I might have trouble justifying it,” says Orms. “Instead, I just decide on the look I want to achieve, and I create it, whatever that takes.” Case in point are the signature Master Collection pieces, which are crafted one at a time, typically of gold. These pieces are carved, cut, and engraved in final form, with no replication or duplication of components. They are truly singular works of art, and some take as many as fifty days to complete. They are the highest representation of Clint Orms’ mastery.

As we walked through the descending back rooms of the studio, exploring the machine shop and the leather shop, the drawers of precious metals and the light booth used to capture images of finished pieces, I noted a grainy, black-and-white photo tacked to a wall. The photo showed a young Clint Orms in his rodeo days, one hand in the rigging of a bronc that appeared wholly committed to getting rid of the boy on his back. The bronc was kicking hard, and Clint was fully extended, his free hand in the air and his boots splayed. There is a lot to see in that picture, not the least of which is the look on young Clint’s face. It is a look not of fear, nor of wild-eyed bravado. It is a look of stern, unflappable determination. It was a look not unlike the one I’d seen on Orms’ face as he leaned over the bench that afternoon, engraving tool in hand.

*

In the fading day, I lingered with Clint Orms as his employees punched out one by one, and the shop grew quiet. He remained at the bench well after closing, and only left the money clip he was working on when a covey rise of tiny gold quail had been braised and accented by a bold and relieved scroll border. The piece remained unfinished, but even as it stood, it was a masterpiece. Clint Orms packed his things, politely held the door, and followed me out. He turned to lock up, and then walked me to my car, and told me a story that he must have been chewing on as he leaned over his work that afternoon.

“You know, years ago when I worked in Australia, my employer had a shop at the Myer Centre in Brisbane. I started there right before Christmas, and there was a seasonal Santa Clause employed at the Centre who used to come up on his breaks to look at our work. It turned out he was an American Indian artist named Michael Red Shirt, and I got to know him pretty well. We became friends. I remember being fascinated by him, and I’d ask him all the time to teach me something about his culture, to teach me something that his grandfather might have taught him. He told me once that if you put enough of yourself into a piece of your work, it eventually take on a life of its own, and it will never die. Michael claimed that forever after, when people pick it up, they will feel the life in that piece.”

Orms looked quietly off to the southwest, where the sun was getting lower over the Guadalupe.

“The more I work and the more I work, the more I believe that what he said is true. That’s been a real driving force for me: to know that when I put enough of myself into each piece, when someone picks it up, they will feel something. Maybe they will feel their hair stand up a little. I like knowing that if I have done my job right, people will feel the life in it for a long, long time.”

With that, Clint Orms and I shook hands, and he backed out onto Old Ingram Loop, kicking dust that obscured the hanging tree. In the falling day, I was heartened to think that things of value still exist, in the hearts of cowboys at least.

First published in Covey Rise June/July 2019