Chasing the Blues

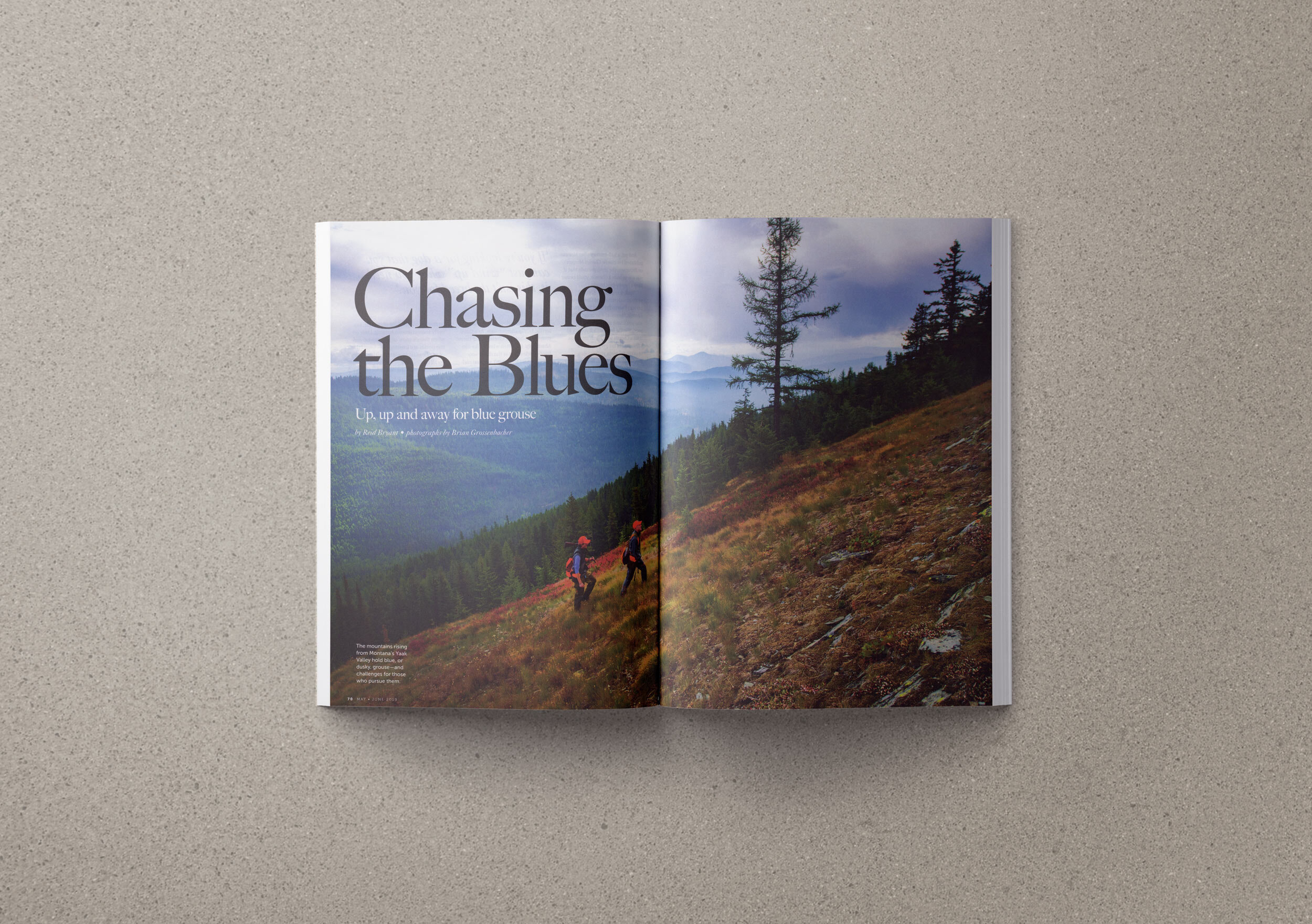

Late in the summer of 2018, the Davis Fire jumped the border, and burned itself out in the conifer forests of southern Canada. The Gold Hill Fire was still inching its way up the valley towards Libby, and as September advanced the smoke was a thin but steady reminder. As we drove up the road out of the Yaak Valley and east, the sharp profiles of the larches and firs were blunted by a halo of finest airborne ash. It was as though the Montana sunshine was doing its darnedest to burn through a haze that it wouldn’t hope to clear, and we could only pray that with elevation we might see some of that yawning blue sky.

We parked high near the pass at Pink Mountain and loaded our vests with water bottles and shells, and shoved cookies in our pockets. Linehan, Christian, and I would cover some ground that day, dragged uphill by two the two rangy setters Maggie and Maisey, and the potential for an encounter with a Blue Grouse or two. This was to be a developing chapter in a Blue Grouse odyssey that has called me back to northwest Montana over several successive years, the promise looming large of big birds in big country. It was just a few miles west and a few seasons past that Linehan and Maisey and I had taken a big bull of a bird off the side of Garver Mountain, the largest grouse of any sort that I’d ever seen framed against the sky. That day, with my legs like jelly and a warm weight against the small of my back, I’d fallen terminally for those birds and that place, the two creating a harmony that will hum in my heart for a good long time.

What I’ve learned to love about Blue Grouse is that they don’t come easy; perhaps more than any upland bird species I have chased, Blues have required of me some substantial boot leather and elevation, and far more hunting than shooting. Perhaps that is why I’ve been so taken by them: Blue Grouse have a way of teaching you something oft-overlooked about being a hunter, namely that you have to appreciate the grinding journey, the long walks and the heavy steps, the tonic potential of some burned cordite but not the guarantee. In hunting, and in Blue Grouse hunting particularly, you are forced to submit to the fact that the best things are earned and not given… and so you set off into a day in the mountains, pitched slightly forward against the grade, sucking hard on air that tastes like smoke and dust and conifer needles.

With our vests full and the dogs already off into the trees we lit out. The forest service trail switch-backed up the mountain and through the larches and pines, casting us through broken shadow. We didn’t bother to load our guns despite that there may have been some Ruffies about in the low-lying timber. We still had a long way to go. The dogs criss-crossed the trail ahead, inconsiderate of our slow steps. At length we broke out into the mountain meadows above the smoke and looked up at the ridge with its bands of green timber. This was ledge-y country, elk-y country, the kind of place that you could look up at and absorb academically but have no capacity to slice into definable blocks of bird cover. And so we leaned back in and kept moving up, knowing that the day ahead would be comprised of a long walk through timber, each footfall punctuating the hope that one of us, or one of those coursing dogs, might stumble into a big and grey-blue bird.

*

For fear of sounding like an ignoramus I suppose I should say right off that the term Blue Grouse is something of a generic misnomer. The long-used term Blue Grouse encompasses what are now recognized as two distinct species, namely the Dusky Grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) and the Sooty Grouse (Dendragapus fuliginosus). Though both predominately inhabit conifer forests at elevation, Dusky Grouse occupy the Rocky Mountain high country of North America, whereas Sooty Grouse, though quite similar in appearance and behavior, are found in mountainous regions from Southern Alaska to California. Although Dusky and Sooty Grouse are distinct species, the two birds nonetheless exhibit similar traits, and similar tactics are required of those who hunt them. They are known to frequent reliable areas year after year, but they do not necessarily occupy a single, concrete piece of cover, as might a Ruffed or even Spruce Grouse. To the contrary, a Blue Grouse hunter has to get up into those bands of Douglas Fir and pine and commit to covering ground, taking big bites out of the country ideally with the help of a rugged and rambling dog. Hunting Blues is perhaps the closest thing in the uplands to pursuing big game in the backcountry or looking for a rising trout in a broad Montana tailwater; it requires some commitment, ample preparation, and a great deal of patience. It comes together somewhat occasionally and not without some luck, and when it does come together it happens quickly. The seconds that comprise either a harvest or a miss are dwarfed by the hours spent in pursuit, and typically it’s a one-and-done deal. When you miss a shot at a Blue Grouse, you might see him descending fast on cupped wings, landing somewhere whence you came a few hours and hundreds of feet before.

It is often said that Blues are stupid, even easy, and indeed generations of western mountain hunters have perpetuated the myth by harvesting their share of Blues with bows or rifles. The Blue Grouse’s occasional tameness has been widely interpreted as genetic idiocy, and throughout their native range they are often maligned by being called ‘Fool Hens’. This is, in my experience, a wholly unfair assessment. Though they will at times flush to the tree-tops to crane their necks and measure your intentions, even then they can be hard simply to locate. And when they do flush, either from the trees or from the ground, they do so with that disconcerting thunder and uncanny ruddering flight endemic to all grouse. When taken on the wing, with due respect to the game, they are by no means an easy target. Moreover, and perhaps most critically, just happening upon them in that big country requires a degree of luck. As writer John Gierach noted, quoting a biologist friend, “for every dumb one you see in a tree, you probably walked by a dozen smart ones on the ground”. Philosophically, I appreciate the sentiment put forth by the Blue Grouse’s innocence: by circumstance and evolution they remain hard to find in places that are hard to get to, and they seem baffled by the concept that such criteria isn’t defense enough to keep them safe from we who wish to eat them.

Both Dusky and Sooty Grouse subsist on a diet that includes Douglas fir needles, berries, and insects, and both tend to move from lower elevations and river bottoms in summer to higher elevations as the season progresses. Mature birds of both species are substantial, nearly half again as big as a mature Ruffed Grouse, with males exhibiting that dark, drab, and dusty gray plumage and the females a mottled brown. The most immediate visual difference in the birds is seen in the males of each species: adult male Sooty Grouse exhibit a yellow throat air sac surrounded by white, and a yellow wattle over the eye during display. The throat air sac of the Dusky is purple and the wattle is yellowish red. The flesh of both species is pink, far lighter than that of a Sharp-tail or Ptarmigan and perhaps just a shade darker than that of a Ruff. In the Yaak, when huckleberries are plentiful, the breast meat can be almost purple and sweet, though regardless of diet it is among the finest game-bird meat for the table. As John Gierach also said, this time of ‘Fool Hens’ as table fare, “a Blue Grouse is often saved for serious game feasts followed by fine port or a seduction”. If that doesn’t sum them up tidily, nothing does.

*

We walked the high ridges of Pink Mountain all day, dipping in and out of the firs. The dogs ranged bigger as the shadows lengthened and the day got still, and at length we stopped to cool them down. I was the highest on the hill in the line we’d been taking, and I sat with my back to the slope and looked down across the valley and into the upper Yaak. Linehan and Christian were a good deal below, chatting quietly about something, no doubt ensuring one another that we’d find ‘em somewhere up here. It had been a hot fall, and a late one, and Linehan had several times postulated that the birds might have yet to achieve the high-country cover of their fall and winter habitat. To me it was somewhat immaterial; just to be back here, walking with friends in good clean country looking for something I’d grown to love… it was more than enough for me.

In the afternoon we took the winding trail down and came out to the road at dusk. We’d not seen a grouse, and the dogs had run big, and were tired. “We’ll find ‘em tomorrow,” said Linehan with characteristic optimism, starting the truck and adjusting the radio dial, smiling at Christian in the passenger seat. “We’ll find em…”

The next morning we set out along the base of Garver Mountain, taking the side-hill logging trace that opened up into aspens and firs. The dogs, invigorated by the promise of new ground, looped up and down into the bigger timber, checking in at points to keep apprised of our progress. We bent around the mountain and kept our elevation as the slope below us opened into a broad, cut-over bowl. We stopped there to water the dogs and take stock. We’d not seen a bird, nor a birdy setter. Linehan was getting a bit concerned, though he was barely letting on. “I’m just not sure where they are, Pal…” he said to me, scratching Maggie’s ears. “I think the fires might have messed things up. We can head back out I guess, maybe stir up some Ruffies down in the valley.” He looked up at the knob above us. “Or we can try up higher, in the bigger trees…” He trailed off. Christian and I both looked up at the knob high above us, the steep hill culminating in bands of green timber. We considered the hard walking, knowing full well that these birds would be earned and not given. And so we started up, kicking our boots into the clumps of crumbling soil and grass.

Several hundred steps above, the pitch lessened. At the top of the knob a grove of Doug Firs gave way to meadow, and then to more timber higher up. I turned and looked back over the bowl, and down into the valley far below. It seemed that the smoke had mostly sifted away, and the colors in the valley floor were sharp in contrast, the edges of color and contour crisp and clean. I looked back uphill and considered a few more steps. Far above, some mule deer does stepped out of the timber, their pale rumps showing lighter than the straw-brown of the meadow. The dogs were casting across and above, and Maggie looped down for a check-in with Linehan, but turned suddenly sidehill with more juice than she’d had all day. Christian, on my right, straightened his weight onto his downhill leg and watched the young dog.

And somehow, from that seemingly comprehensible piece of ground just ahead of us, two birds we’d not seen fractured off and thundered up, landing in the trees above us. Christian closed his gun and so did I, and Maisey came in to join the fray. Before we’d gotten a clean look at the roosted birds one dropped from his branch and flapped hard downhill, and Christian tumbled him with a left barrel. He and Linehan and the dogs set out downhill in pursuit, and I just kept looking hard in the treetops for something designed not to be seen. After a time, the fellows and dogs regained the hill, Christian smoothing the fine, grey-blue bird in his hand. Linehan was craning to see the remaining grouse in the branches above, but I was already giving up.

“I think it must have busted while we were watching Christian’s bird,” I said, becoming increasingly certain that our damage for the day had been done.

Linehan wasn’t so sure.

“Watch the young dog!” he said, and indeed little Maggie was zigging and zagging up the slope, clearly working out a problem of consequence. I closed my gun again and moved in behind her just as another bird broke free and gained requisite clearance, then set off at a low downhill slant. I’d not had a chance to get a good look at this bird, to study him on his branch or consider the vagaries of his impending departure, the innocence in his unblinking black eye. I hadn’t even had the chance to think about my tired legs and the long ridgetop walk that might, if I missed, present ample time to chew on the legitimacy of my disappointment. This one I managed because a big Blue Grouse flushed from the ground and found himself outlined against a backdrop of northwest Montana, and I didn’t think about any of it too hard. I swung through and pulled the trigger, and there he was, tumbling down into the young timber and grass just below us.

*

In the end, my Blue Grouse odyssey likely does not rationally justify the time away, or the cost of getting there, or the sore knees and creaky back at day’s end. In a sense, too, I’m an interloper here, as much a non-native of this place as the pheasants on the prairies to the east, or the chukars on the canyon country to the south and west. In some ways these are not my birds, just as these are not my hills; when I go to find them, I am walking into a land that I’m falling in love with but do not yet know. But what I do know, and remain grateful for, is the fact that Blue Grouse are delicate, tiny pieces of a great big landscape, a landscape uninterrupted and largely untracked, and fundamentally wild. In the scope of their cover, the places where we hunt them, they are veritable haystack needles. And yet, bizarrely, when we do find them, they are as large in the context of our small hands as they are dwarfed by the mountains in which they live. Blues are magnificent and heavy, innocent and true, hard to hit and hard to find, treasures to be sure. They tempt us outward and upward, tease us over mountains and miles, reward us at times with their delicate flesh. They make hunters out of us.

I suppose that’s why I’ll keep chasing them… for the certainty of the journey and the potential of the destination. That, and the prospect of a port and a seduction when it all happens to come together.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine