The Remains of the Moment

Far to the west, a storm slips down the seaward slope of the Maya mountains, obscuring the jungle and splattering the coastal sand. It piles up where the land meets the sea, uncertain whether to press on over the water or play itself out in a fit right there. The storm rumbles and flashes, and on the periphery of it the waters south of Tobacco Caye, fifteen miles out, go to glass. The air crackles and gains density, and Lincoln Westby pulls back the throttle and kills the engine. He tilts it up with a hydraulic whine, and in the leveling silence, water barely laps the chines. The frigate birds have gone away, and the storm tries hard to convince us of its enormity, or perhaps convince itself.

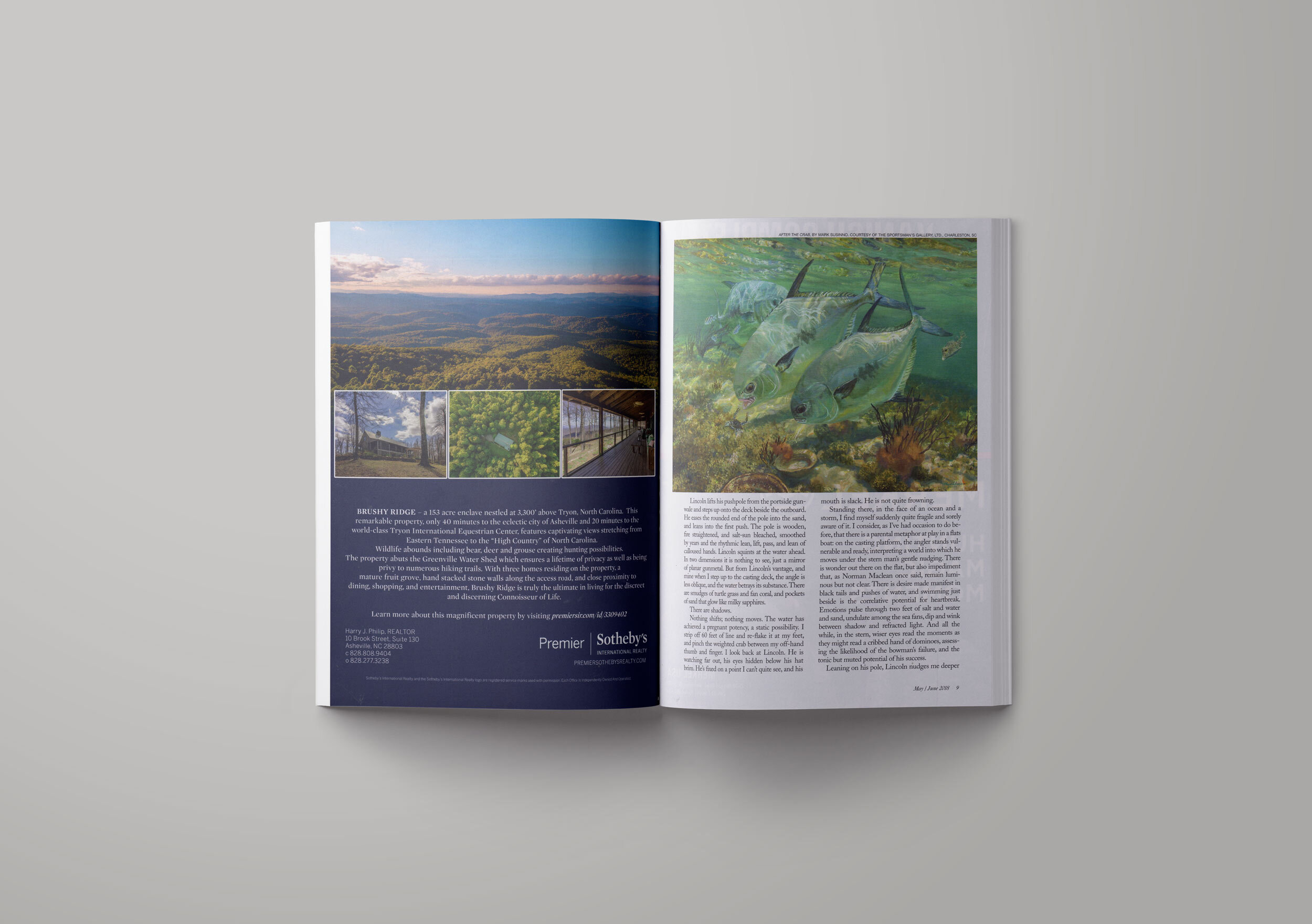

Lincoln lifts his push pole from the port-side gunwale and steps up onto the deck beside the outboard. He eases the rounded end of the pole into the sand, and leans into the first push. The pole is wooden, fire-straightened and salt-sun bleached, smoothed by years and the rhythmic lean, lift, pass, and lean of calloused hands. Lincoln squints at the water ahead. In two dimensions it is nothing to see, just a mirror of planar gunmetal. But from Lincoln’s vantage, and mine when I step up to the casting deck, the angle is less oblique, and the water betrays its substance. There are smudges of turtle grass and fan coral, and pockets of sand that glow like milky sapphires.

There are shadows.

Nothing shifts; nothing moves. The water has achieved a pregnant potency, a static possibility. I strip off sixty feet of line and re-flake it at my feet, and pinch the weighted crab between my off-hand thumb and finger. I look back at Lincoln. He is watching far out, his eyes hidden below his hat brim. He’s fixed on a point I can’t quite see, and his mouth is slack. He is not quite frowning.

Standing there, in the face of an ocean and a storm, I find myself suddenly quite fragile, and sorely aware of it. I consider, as I’ve had occasion to do before, that there is a parental metaphor at play in a flats boat: on the casting platform, the angler stands vulnerable and ready, interpreting a world into which he moves under the stern man’s gentle nudging. There is wonder out there on the flat, but also impediment that, as Norman Maclean once said, remain luminous but not clear. There is desire made manifest in black tails and pushes of water, and swimming just beside is the correlative potential for heartbreak. Emotions pulse through two feet of salt and water and sand, undulate among the sea fans, dip and wink between shadow and refracted light. And all the while, in the stern, wiser eyes read the moments like they might read a cribbed hand of dominoes, assessing the likelihood of the bow-man’s failure, and the tonic but muted potential of his success.

Leaning on his pole, Lincoln nudges me deeper into a space where magic dances, lacerating the water’s surface, in the same place tragedy looms near. He leans on his pole and urges us on, as he’s done with all those who’ve come before me, only to watch as a parent does a love-struck son who blunders into the arms of the vixen girl. He may, in my palpable intention, see the scales of power tipping, see in the width of my stance and the lean of my back the butterfly-wing fragility that desire has spawned. He reminds me to keep the cast low and soft as he watches the flat slowly open before us, and perhaps he remembers the paper-cut sting of his own youth here, though the memories may be dulled by years. I’ve come to believe that he always hopes, but never expects, and in that lies his strength, or at least his shelter.

Lincoln Westby leans on his pole and moves us silently along. We glide further onto the flat. Behind shaded eyes he sees the sickle tails well before I do, but doesn’t say a thing. He seems to know I’ll see them in due course, and a racing heart will do me no good in the coming span of seconds and slipping water. Inflated desire might only upset the viscosity of the next few moments, of a hundred feet of mirrored glass, of an un-rippled silence. The storm rumbles inland, and flashes purple.

Lincoln would say later that in all of his seventy-six years, he’s known nothing that so makes a grown man fall to pieces as a Permit. “It da tail…” he’d say in a voice marinated in Creole song. “It nuh mattah ifa yuh caught a hundred a dem. Da man see da tail and he fall apaht...” Indeed, the flailing sickle of a Permit tail somehow condenses longing and intention into something that sears the heart and confounds the synapses and cuts to the bone. And then at seventy-five feet I see them: the upper halves of two black tails, a dorsal, an arc of back… two fish floundering lazily, unconcerned. Permit look down to feed, and Lincoln wagers his stealth against their animal hunger, and glides not in but alongside them. I cannot look to see his face, but in a voice I suddenly remember from grade school I whisper-squeak. “Tell me when to go…?”

He doesn’t respond, and we slip closer.

I flop the fly and twelve feet of line onto the water, keeping my rod tip low and out and back. I look around at Lincoln.

Silhouetted against a thunderstorm, he’s somehow outside of time, outside of space. All he sees, all he hears, all he appears to know in this moment is Permit tails, and the abstract notion that when he says go, I will fire a curl of fly line that is heavy with intent, and almost surely send them on their way. There’s an intimacy between man and place and fish right now into which I somehow don’t fit, and this registers, but does nothing to lessen my desire to be a piece of the scene unfolding. I’m a pink foreigner out here in a land of deepest blues and glinting silvers and soft bronze browns… and despite my irrelevance I want one of those sickle-tailed beauties. I turn back to them.

“Now?” I whisper.

Forty feet.

“OK,” he says.

Lincoln’s pole crunches into sand, and wedges us there. His go-ahead is less a directive, more an acknowledgement that his choreography has ended, and the moment is now mine, to make of what I will. His control ends and my rod tip starts to move, accelerating line forward and back, hauling one last time to deliver a weighted crab facsimile into the circle of light and water and motion that now, and for years, has substantiated him. He has delivered me with delicacy into a place of swollen possibility, and now he lets me loose. I cast, haul, slip more line between my fingers, haul again, and let it go. In slow motion the loop of line unfurls, and the crab descends.

Spooked Permit can explode and run in a heart-stopping display of flight that punctuates an angler’s ineptitude, convincing him of it. At times, like those vixen girls whose affection was so coveted, they simply turn and go, mildly disgusted by a mere man’s self-assessment as one worthy of a dance. And sometimes, they simply disintegrate.

Lincoln looks around and down the flat, scanning, his jaw set, his eyes still shaded. The temperature drops suddenly, and a light wind penetrates the stillness of our sphere, wrinkling our water. He looks on, further out.

I turn back to him for guidance, for an indication of where the fish have gone, for some explanation of how I sent them away. He doesn’t offer anything. He shifts his pole from port to starboard, and leans again to push. He has begun to smile.

The boat pivots on the pole, and I strip in, collect the fly, pinch it again. Lincoln’s pushes are stronger now, and in our movement I feel that he has scooped up the remains of the moment from where I left them, and taken possession of them again. In that there is no judgment, but a descending finality. The cold air comes hard now to push us, and the surface of the flat fractures and lifts, darkened by little squalls, peppered by pushed rain. I feel anticipation and a thready pulse spiraling slowly out, a coreolis around my bare feet that will seep into the bilge. I reel up, step off the platform, and sit.

Lincoln leans on his pole and it crunches. “Heh, heh…” He laughs gently, and in his laugh I again see that this is a moment only, just a small sliver of a larger story, and at the same time all there is. “Dey no bettah teachah den de Permit...”

The storm, loosed of its hesitancy, comes in without shame.

First published in Gray’s Sporting Journal