The Coincident Ecology of Birds and Men

The scrub steppe of western Patagonia is not exactly welcoming. It’s beautiful for sure, breathtaking even in that lean, hard way that exposes a geologic musculature, one unsoftened by an ounce of fat. The expanses yawn, the ridgelines tear the sky into ragged profiles, and the suggestions of human habitation are, at best, few and far between. In considering that country, it becomes something felt more than seen, enhanced by the realization that it could swallow you whole, puncture you with thorns, turn you into rawhide with sun and wind. Not with malice, but dispassionately, as if to say, “you were the one that wandered out here in the first place”.

Subjective is the view of the beholder, though, and welcoming or not, that is where this story takes place, in the hills of western Patagonia. It is, at heart, a tale of convergence, one in which the songlines of birds and men coincide on the Andean steppe, on arid ground between calafate bushes and clumps of coiron grass. In those unapologetic places, Rance Rathie and Travis Smith found a land to call their own, a unique ecological niche, one shared by an equally unlikely species of North American quail. Both men and birds trickled into that space from well above the equator, filling a vacancy that neither knew was in want of filling. Serendipity, perhaps. But it makes for a great story, one appropriately poetic, befitting the backdrop, the setting, the cast of characters, and a region as lonesome as anything described by Frederick Remington or Zane Grey.

The first whispers of this story drifted out of the Andean foothills in the year 1943, when a Chilean aristocrat was invited to visit the Lariviere family at their Estancia La Primavera in Neuquén Province, Argentina. Legend has it that the guest was at once awed by the place, the arterial Traful River and the spare, brushy hills which rose from its waters to the high serrations of the Andes. Following his hosts through the property, he likely found in the arresting beauty that his homeland over the mountains was somehow less impressive than he’d previously thought. The flames of his nationalism flickering, he wondered aloud why the place was void of the California Valley quail that proliferated in his native Chile, having been introduced nearly a hundred years before. The land looked suitable, and surely the presence of the top-knotted birds would enhance the place a little, provide cowboy poetry of a sort. Lariviere had no good answer as to why there were no quail. So, in 1944, the Lariviere’s onetime guest made a gesture demonstrative of Chile’s aristocratic set: by air he shipped eight braces, male and female pairs, of Callipepla californica first to Buenos Aires, then to Bariloche, then by taxi to Mr. Lariviere at his home on the Traful. Poetry in flight, albeit by airliner. The birds, no doubt beleaguered from their journey, were held together in an aviary for several months and cared for by the Estancia’s manager. To the disappointment of family and staff alike, the birds failed to reproduce, and only haltingly infused the Traful valley with their high and reedy calls.

On the night of December 24, 1944, the Lariviere family assembled a party of family and friends, revelers gathered to celebrate the Christmas Holiday in the heart of Argentine summer. Upon the advice of his estancia manager, and no doubt informed by wine and the mythos of the holiday, Lariviere made a ceremonial gesture: at the stroke of midnight, in the very arrival of the nativity, he released the sixteen birds upon the landscape, relegating them to their fate, perhaps challenging them to survive and the Andean foothills to help them do so. If you love something, set it free, as they say. As the little birds scurried off into the night, none could know what the ensuing half-century would bring.

In monumental understatement, the birds made it through. In the decades that followed that Christmas morning, the hillsides and river valleys of Argentine Patagonia took the little birds in their sinewy embrace, saw to their protection, nudged them into sheltered corners where they became plentiful. That reedy call, unrestrained by wire cages, rang out with increasing conviction over the decades, the dusty soil becoming littered with dainty, 3-toed prints.

A half century later, among those same overlooked corners, two men from Montana would find their place as well, would leave their own footprints, hear their own emphatic voices echoing off the hills. They too would thrive on that ground, scratching out a livelihood, etching a story into the grit and solitude of western Patagonia.

*

Late in the 1990’s, Rance Rathie and Travis Smith left their hometown of Sheridan, Montana in pursuit of bigger trout and bigger mountains, yet unaware that the threads of their story would tie them inextricably to Argentina. In the 1980’s and early 90’s, Sheridan was one of the last good places. Yet largely untouched by the Hollywood idyll conjured by Brad Pitt and an elusive 4-count rhythm, the Ruby River valley was rough-cut but unpolished. The bounty of the place was geologic: The Big Hole, The Beaverhead, The Jeff, The Ruby proper… cold and clear through the valleys, underlining the jagged height of the Tobacco Roots, the blunted peaks of the Gravelly’s and the Snowcrests. It was a place hard and proud and defiant, rich in fish and game, confident that its ranch-hands, card players, and outfitters could throw a punch and take one too.

When you grow up in a place like Sheridan, you are instilled with a native pride that compels you to show the world outside that you too are hard and proud and defiant. It’s a coming-of-age that requires a small-town kid to size himself up against the world beyond his zip code, to scrap with the kids from Dillon and Butte, to go fish circles around the guides from over in Idaho. Rance and Travis grew up in the shadows of mountains, within earshot of rivers, and they took up the tools of the regional trades, ones equally valuated in real and cultural currency. They shot elk and grouse, teased trout out of eddies and logjams, played baseball and spit Copenhagen. They learned to fight a little and drink a little and to tell good stories, some of them true. Maybe they even started to swagger a bit, the certainty in themselves reinforced by their confidence in each other. They began to wonder how they’d fare on a bigger playing field in which the rules were the same, but the stakes were bigger, or at least less clearly defined.

The immediate vehicle for Rance and Travis was fly fishing, and the hallowed destination Argentine Patagonia. The fly shop magazines of the era and the better-heeled clients in the bow seats of their drift boats described Argentina as a place of thorns and edges, riverine capillaries that were haltingly cold and full of fish, ridgelines that composed the sky’s dentition. Patagonia afforded tough country without ostentation, the honesty of it sufficient to knock the wind out of a guy, which made for a kind of tempting romance to a couple of Montana kids, with a hint of a dare as a chaser. After summer days spent rowing their rivers, Rance and Travis would return to Sheridan to drink beer and to contemplate a big adventure, one filled with south American trout, the earthy flavors of wine and meat, and beautiful, smokey-eyed women.

And so, being young and tough and untethered, they went looking. They parlayed that currency earned in the Ruby River valley into jobs as fishing guides, in a land both foreign and familiar. They took their punches in the early years, realizing the isolation of a language barrier and the nuances of a cultural amalgam both wild-west cowboy and patronizing-ly European. They got swindled by employers, lost some money and some innocence, and came out of the first few seasons quite confident that they could do it all better, make better use of the region and the opportunity that resided there. The trout were a foregone conclusion, the meat and wine a reward all their own. The women were prettier than they’d been told.

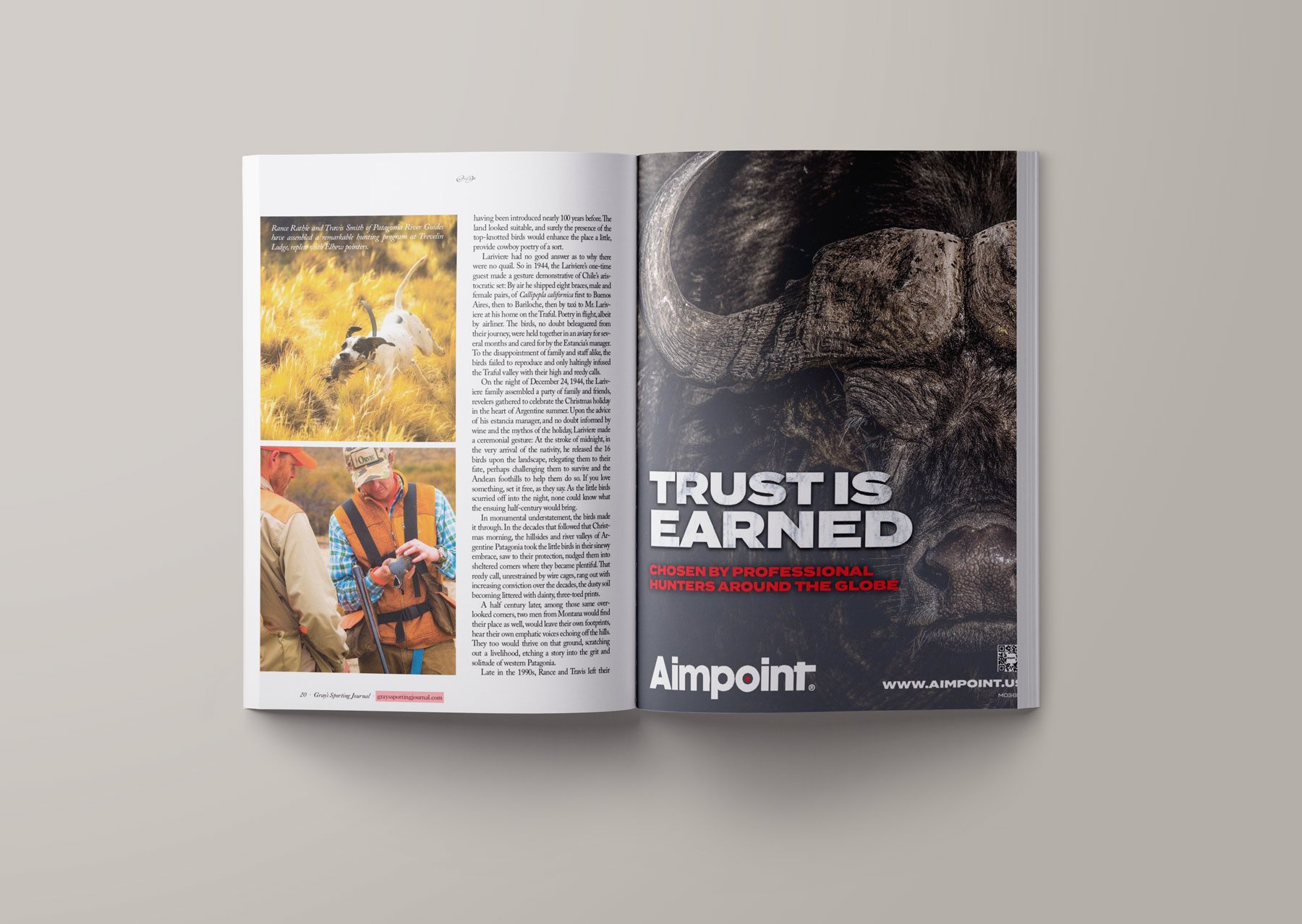

As the early 2000’s came around, Rance and Travis spent larger and larger portions of the year in Patagonia, building a business called Patagonia River Guides. They learned Spanish, bought property, established a vast network of relations with local landowners, gained access to water as pristine as any, and full of fish. They imported boats and tackle far better than what had been regionally available prior. They purchased and renovated a lodge in Trevelin, broke ground on a vineyard, pioneering the cultivation of grapes in the southernmost wine-making region in the western hemisphere. Rance married Ellie, a local woman, and started a family, enrolling his children in the local schools. And all the while, throughout the slow but steady immersion into western Patagonia, Rance and Travis noticed another character in their story recurring with increasing frequency, making its presence known: the California quail.

Though the men had noticed birds here and there since their early days in Patagonia, the numbers of quail just seemed to blossom each year. By 2010 or so the birds were in sufficient number and range that when fishing the Corintos, the Rio Percy, or any river that nudged up against the Andes, PRG guides and anglers would scatter coveys of skittery birds off the roadside, hear their calls bouncing through the valleys. Guests started to inquire about the hunting possibilities. Seeing an opportunity, and recognizing an experience that they’d come to know well during a Montana boyhood, Rance and Travis began shaping a hunting package of similar elegance and quality to the fishing program they’d become known for. They gained hunting access from Estancia owners who looked at them quizzically when asked for access and quail to hunt. They imported Elhew pointers from the States and brought in sufficient shotguns and ammunition to outfit a spring season of hunters and anglers who enjoyed a good day’s walk as a complement. And then they flipped the switch.

What transpired was an upland experience unlike anything then offered in Argentina, and exceptional compared to any quail hunt anywhere in the world. Massive tracts of land, classy dogs, coveys numbering in the hundreds, and rarely a property hunted more than once in a season. With warming climatic trends and forgiving winters, the populations of quail just kept growing, and with PRG’s self-imposed bag limits, the birds came to represent arguably the best kept secret in bird hunting.

The convergence of men and quail in a particular ecological niche… and each growing stronger, or at least more appreciated, for the convergence.

*

Guide Adolfo Alonso steered the truck off the two-track, braked, and killed the engine. A hush seeped into the valley and through our open windows, tinks and hisses of a motor retiring becoming the only non-native sounds. Adolfo opened the door and stepped out into the day. Rance Rathie, Travis Smith and I followed suit. Adolfo took a few steps away from the truck to inhabit the area more thoroughly. He looked out over the sprawl of ground, a bowl filled with variegated greens and browns, a river bisecting the whole, an upswell to the west all crumbled rock and thornbush. He stood statue still, emphatic in brush pants and boots, and assessed the situation. A breeze came off the sidehill, slipping down the rise of the Andes, a geologic exhalation neither exasperated nor resigned. It washed the residual noise from the place and left it clean and still.

Rance lit a cigarette and squinted through smoke. Travis came around from the far side and leaned against the truck hood, coffee mug in hand. We all watched Adolfo. He shoved a hand in his pocket, then lifted something to his mouth, hunched his shoulders, took a breath, and blew. A high and reedy sound cut the day like a switch.

“hee-HEE-he…” he said. “hee-HEE-he…” again, and the second call cut off in a pregnant declamation, a question mark implied. We listened. Somewhere far off and below, in among the scrub and scarred earth a response echoed back, lighter over the distance but no less clear. Adolfo turned his head in that direction and listened for another minute. Then, satisfied, he tucked the call back in his pocket, turned around, and nodded his head in affirmation.

While Adolfo rattled about in the truck bed collecting dog collars, shell boxes, and bottled water sufficient for a long walk, Rance and Travis just waited in that anticipatory stillness, sufficiently confident in what lay ahead that to rush into it would be antithetical. We stood there together while Adolfo collared the dogs, and the day before us became a trove of possibility. Rance and Travis were chatting idly about days gone by, some childhood misadventure back in Sheridan that had a distinctly Huck-and-Tom Sawyer sort of flavor. Rance tied up the loose ends of the story with some clever turn of phrase, and Travis and I giggled.

“Well…” said Rance, pinching the ember off his cigarette and pocketing it. It was neither a question nor a statement, and it didn’t really stir any of us into action. The birds were there and would remain, and the slow approach, the savoring of the moments, those were the places that Rance and Travis chose to inhabit, doing so happily and well.

Adolfo? Not so much. His agenda was more time-sensitive, and he had dogs down and making game already. Rance shrugged into his vest and Travis screwed the top back on the coffee mug. With a look, Adolfo nudged us into motion, and we walked out into western Patagonia and her untold wealth of quail.

Those who have hunted Valley quail before might recognize the habitat of the Andean steppe in aggregate as something similar to eastern Oregon or high-desert Idaho, or even bits of the Sierra Nevadas, but the unique pieces will be different. Key to locating quail in this region is the identification of a mallin, or a spring seep that saturates a portion the ground, ever-present moisture keeping the immediate surroundings vegetated and fostering the growth of specific bunch grasses and fescues that the quail rely on for food. Extending out and uphill, the quail seek cover and protection, but also navigable pathways. The scrub zones of the steppe are studded with clumps of brush and brushy draws, stunted trees, and impenetrable clusters of califate, manca caballo, uña del gato, chacay, into which the quail are wont to disappear. Predators from land and sky are few, and like us leery of the thorns.

Adolfo, long ago recognizing the hazards of kicking into these prickly places, and the correlative unwillingness of the pointers to try, developed a flushing tool of sorts. To the end of a long piece of river cane he affixes a plastic water bottle, one that crackles and crunches when thrust onto the brush. Something in this physical and auditory invasion of privacy proves wholly not ok to the quail, which spill out of the bushes like angry bees, dodging through the brush and the roll of the ground. The shooting is, of course, fast and furious.

We cover the sidehill above the bowl first, hitting the shallow draws, while Adolfo hustles up and downhill, plunging his lance into the bushes. The pointers make their big casts and swing back into birds they’ve passed, often locking up on the calafate bushes, articulating the pinpoint of convergence, to which we are all drawn. Rance and Travis swing along after the dogs and shoot at the flushes, happily knocking down birds in that unhurried, unpressured way of guys who have done this before, and know they will do it again.

We stop on a height to catch our breath, and Adolfo calls in the dogs for water. Travis breaks his gun and plunks down in the soil, and we all look out over the bottom of the bowl, which, from this aspect, is a vast swath of brown studded with brush. Rising from below us is that thready, wheedling call again, and Travis points, indicating the general area from which the call has come. Following his finger, I look down and see what he is seeing, the ground alive with scurrying motion, birds as small as ants from up here, but remarkable in number. Travis just shakes his head, amazed perhaps at the way in which the quail have thrived so readily in this place.

Rance has lit another contemplative cigarette, and he has his gun broken over one shoulder. He is rolling something around between his thumb and finger, and he sees me looking, and holds it up. It’s the small, blue berry of the calafate, a regional treat enjoyed by locals in the Argentine autumn. It is also the subject of an enduring mythology shared widely, and with a sincerity that is disarming to the average, cynical American. “The say that any visitor who eats a calafate berry will return to Patagonia,” says Rance, taking a last look at the berry before popping it in his mouth. He rubs his finger and thumb together, looks at me, and smiles. “I guess it’s a good story, and pretty accurate.” He looks over at Travis, and back at me, and shrugs. “In our case, though, we didn’t have to come back… we never really left.”

With that, Adolfo has the dogs watered and back on the hunt, and a long walk downhill will put us into the thick of things, the heart of the cover, a place teeming with quail. We each have a few to go before our limit. But Rance and Travis don’t hurry to load their guns and start moving, though I do share Adolfo’s inclination, and I have yet to try a calafate berry. This may be a singular day for me, but I temper myself and sit there a heartbeat longer, watching Rance and Travis, looking down and far off at a place both vibrant and severe. All the players seem to fit perfectly, and there is no reason yet to rush into what we know lies just ahead. For some, I suppose, no reason ever to rush, to look beyond, or to think that anyplace could be more perfect, or feel more perfectly like home.

If You Go

Patagonia River Guides operates Orvis-Endorsed quail hunts in a limited season in Argentine spring, from April 1st to June 1st, generally based out of the lodge in Trevelin, Patagonia. Travelers from North America typically take an evening flight south, landing in Buenos Aires in the morning, and most enjoy a day and evening in the city before boarding a domestic flight to Esquel or Bariloche. Hunting days are often interspersed with fishing days, which allow for a diverse experience second to none. Expect long walks in tough country, and a self-imposed bag limit of 15 birds per day per gun. Elhew pointers and professional guides round out the hunting day, and small-bore Beretta O/U and autoloading shotguns are available for let.

Guests at PRG’s Trevelin Lodge will experience the pinnacle of service and refinement, with elegant rooms, exquisite cuisine, and a comfortable but classy environment. Rance Rathie and/or Travis Smith are typically on-site to host, and both the hunting and fishing guide teams are proficient in English. PRG’s staff sees to it that logistics are personally attended to throughout the travel experience, and they are happy to assign handlers to facilitate the Buenos Aires experience. For more information see https://www.patagoniariverguides.com/hunting-patagonia/quail-hunting/ or https://www.orvis.com/patagonia-river-guides-argentina/2P1Z.html or email INFO@PATAGONIARIVERGUIDES.COM

First Published in Gray’s Sporting Journal