Striving

Centennial Park was on the far side of my childhood town, and a half-hour bike ride across a 4-lane highway. There was a pond there frequented by me and the dog walking contingent, and the occasional pot-smoking high-schooler. It was a homely little thing, no bigger than a baseball infield, with sloping banks and a brushy tangle that obscured the deeper far edge. A brook trickled in and then trickled back out, until mid-July anyway. At that point, both inflow and outflow became parched trenches, and islands of green scum bloomed on the pond’s surface, sending gossamer tendrils into the depths. The Park always smelled like honeysuckle and dog shit and dead shiners, an olfactory melange that describes my childhood still.

On lazy July evenings I’d pedal over there with a rod and a film can of popping bugs. In the still-long days there always seemed to be a thunderstorm grumbling on the horizon, rarely amounting to much. I’d ditch my bike against a wooden bench and rig up, swatting mosquitoes against my legs and wishing I’d remembered to sluice myself down with Cutter. I’d tie a few feet of Stren to the end of a pigtailed leader, attach a small bullseye popper to that, and take a long slug of Ginger Ale (a childhood weakness) from my water bottle. Then I’d head down to the water’s edge, where the shallows were already swirling and popping, alive with stunted bluegills.

This is a portrait of my youth, my beginnings as a fly fisher. July evenings and bug bites and pond scum and bluegills proved endlessly hopeful for me then, and nurtured a love that remains one of the few that I’ve ever been true to. And yet these memories are entirely unimpressive; there are no grip-and-grin shots to commemorate them, no artful presentations which brought great fish to bear, no Rajeffian casts that presented a bug so fine and far off that the hapless quarry, mesmerized by my sleight of hand, fell victim to my wiles. For much of my life, I was a bug-bit kid noodling bluegills out of a suburban pond, and stepping in dog shit when I wasn’t careful. And it was more than enough. I bring this up on account of the fact that I am getting old, and possibly curmudgeonly. I am, as a I write this, looking down the home stretch of my first forty years, and being forced to acquiesce to middle age. With this, I struggle to make meaning of a shifting reality, and my responses to it. The gray in my hair saddens me; the squishiness around my middle maddens me; a refining taste for decent bourbon outstrips my ability to afford it. I realize now, as we all must, that youth is indeed wasted on the young, as George Bernard Shaw could attest. But my struggle is less simple than a lingering resentment for graying hair, and a longing for the youth that is eluding me. My struggle straddles empathy and acrimony, for I, as my forefathers, see a great failure in the youth of today. And I owe this debt of rancor to Mark Zuckerberg, the Godfather of social media.

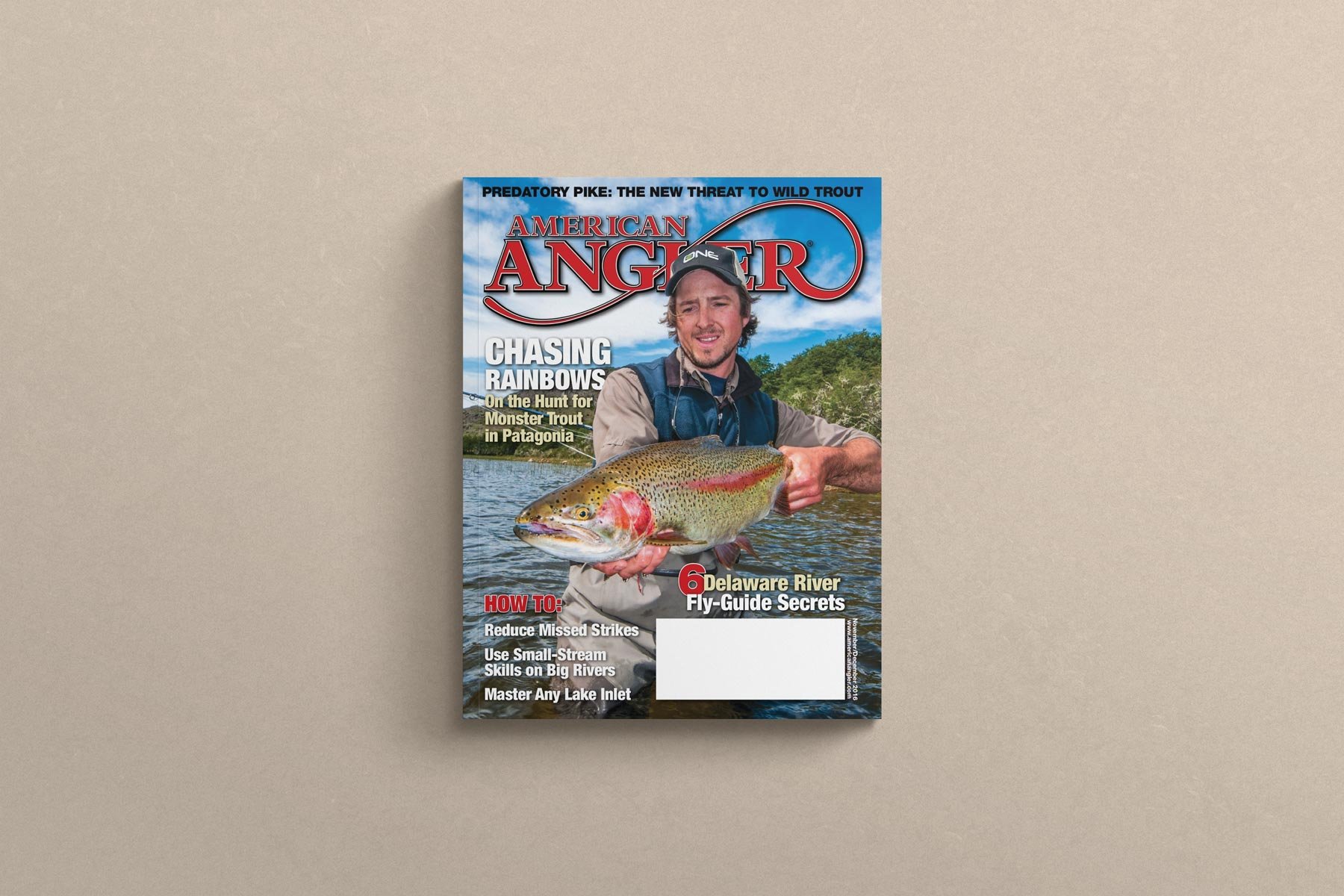

There is a sentiment out there these days that Facebook killed fly fishing. To my aging and increasingly less strident way of thinking, this is a bit of an overstatement, intended to sell t-shirts and bumper stickers to the tragically hip. It is true, however, that young anglers have run amok in recent years, posting a parade of images for the world to see, portraying heroic catches held at arm’s length, as if to certify said angler’s expertise. The nay-sayers claim that this steady documentation of big fish allows other anglers some precious intel… “you can see from that big forked cottonwood that he’s fishing the trestle pool on Deer Creek; now everybody knows that spot!” Indeed, the players are gonna play, and the haters are gonna hate. But what I find more tragic, and more disheartening, is that the preponderance of Facebook grip-n-grins, this steady parade of increasingly gargantuan brown trout and muskies and permit on behalf of our friends and friends of friends, might well make us strive for something that isn’t based in reality.

Indeed, Facebook may be setting us up to feel cheated by fly fishing, a graceful art that deserves far better. Art Webb, an advertising guru and former Michigan fly guide, recently presented a bunch of fly fishers in a room in Missoula MT with this very observation. Said Art: “Why are there so many pictures of big brown trout out there on the internet, and where the hell were all of those fish when I was guiding?” I wonder the same thing.

Now I am the first to tell you that Facebook has not killed fly fishing. Fly fishing, like love and SPAM and poetry and the Herpes simplex virus, defies adversaries far stronger than the will of man. The challenge is, and the tragedy is, that Facebook nurtures a culture of striving. It makes us look at the big brown trout and wish they were ours, makes us wish we were there, makes us feel somehow that what we actually did was somehow inadequate. The stocked brookie as long as a ruler that made our heart soar risks discreditation by the squaretailed behemoth in a friend’s profile picture. And the insidious part is that these fish are not being caught by the rarefied few anglers who grace the magazine covers and write the books. By Facebook’s very design, they are being caught by our peers, our fellow commoners, they guys who fish where we do. And that makes us wish all the more for what we do not have.

Fly-fishing writer and former American Angler Magazine editor Phil Monahan recently gave me a copy of Walker Percy’s brilliant essay ‘The Loss of the Creature’. In it, Percy discusses man’s inherent disability to be ok with our own, unique (sovereign) experience. Instead, says Percy, man tends to be overwhelmed by “the disparity between what it is and what it is supposed to be”. When I look on Facebook and see a parade of dripping leviathans, and backdrops of pancake flats or powder-peaked mountains, I cannot help but be overwhelmed by the same.

Rewind nearly thirty years, to a time before the interweb. Breathe in deeply and smell the honeysuckle, and hear the pop of bluegill lips on lily pads. Feel the immediacy of the sting-itch when the mosquito buries his proboscis to the hilt, and you wheel back and swat him away, and your dirty tennis shoe sinks into something soft and stinking. Shuffle down to the water’s edge and cinch the knot on the popper tight and snip off the tag with an old pair of nail nippers, and stuff them in the pocket of your cutoff jeans. Work out some line with a noodly 9-footer, throwing open loops, snagging a clump of grass on a bad back cast, creating a mess. Take precious minutes to untangle, your heart pumping as the bluegills swirl and the American toads chirr and the bats and nighthawks start to swoop. Regrouped, untangled, flop out a cast and barely give it a chug before it gets tapped, punched, poked, wrestled under the surface. There’s a swarm of them there hovering just underneath the bug, taking turns, taking lazy swings and barely connecting. Wait patiently for real contact, swatting at your bare legs with one hand. At last, the bully of the group engulfs the little popped, the yellow stripes disappearing into his suction cup mouth, the whisps of bright hackle growing abstract beneath the surface. Set the hook. The rod tip dips and wiggles and dances all around. Strip him in, never yet in your life having had cause to use the reel. He planes back and forth, as a sailboat tacks steadily into a headwind. Bend and grab the fish, a spiny slab of life that is roughly as big as your palm. He’s radiant blues and reds and blacks and golds and silvers, punctuated by a stark blue-black at the gill plate. Settle his fins and look at him face-on, and poke the popper deeper into his mouth with one finger, disgorging the hook. Drop him back without ceremony, and stand up, and flop out another length of line. A barred owl calls in the hardwoods on the hill.

This is, as Marge Piercy said, ‘as common as mud’. This is fly fishing to so many. It cannot, maybe should not, be aspired to. It doesn’t look good in a picture, and it won’t garner many likes or follows. But it is real, and lovely, and where so many of us began and return to. Or maybe I’m just old and jealous, wishing for all the world I could catch one of those big ole hook-jawed brown trout.

First published American Angler Magazine