Salmon Snob

Atlantic salmon anglers are, by nature, gluttons for punishment.

My friend Matt Breuer is not a glutton for punishment. He is, however, a glutton for all sorts of other vices, not the least of which is gluttony itself. If there’s a 24 pack of Pabst in your fridge that needs finishing, then Breuer is your man. On a recent visit to my home, he volunteered that he’d recently taken an inventory, and had found himself the proud owner of forty-one top-shelf fly rods. Forty-one. When pressed, Breuer asserted with a shrug that “only an asshole” would own any fewer than twenty-five. An ascetic Breuer is not, but a salmon fisher he is… and a very good one at that.

Atlantic salmon anglers fall into a peculiar subculture of fly fishers who, with rare exception, expend extraordinary amounts of energy to not catch fish. Dismal catch rates are almost a badge of honor, and, oddly, the least successful salmon angler is frequently considered the most steadfast. In the fire-lit study of a Scottish sporting estate, one ruddy faced gent might allow “I went two years on the Tweed without raising a proper fish…” whereupon a fellow sport, quaffing his brandy and adjusting his ascot, might reply with a smug “Ahhh… only two? I went three full seasons on the Tay without so much as a touch...” But then, if ever a heartbreaking symbiosis were to exist between predator and prey, then the Atlantic salmon fills its role to a snap-t. Salmo salar, like nearly all salmons, boasts the peculiarity of refusing to feed upon entering the spawning cycle, when, within cold flowing water, fly-fishers try to catch him. Unlike the Pacific salmons, which dutifully perish after the herculean effort of the run, Salmo salar returns to torture the masochistic angler year after year, shunning beautiful flies that resemble nothing in nature but cost, often literally, a king’s ransom. To bastardize the oft-employed maxim, most Atlantic salmon ‘fishing’ is ‘fishing’ to its core, as ‘catching’ only seldom enters the equation.

So how is it possible that my friend Matt Breuer, the barrel-chested, bull-necked, glutton for gluttony who squirms like a second-grader when forced to sit still, came to be an Atlantic salmon angler? Well, in a sense, it was a three-stage process: first, he assumed that most Atlantic salmon purists were dogged slaves to tradition who’d sooner be caught with their ‘plus-fours’ ‘round their ankles than go after their quarry with any cowboy conviction. Second, he theorized that if a benevolent God put silver-scaled fish in rivers, then that same God set Matt Breuer upon His good earth to catch them. Third, he brought his convictions to bear: Breuer located the one river on the planet where Atlantics could be caught hand-over-fist, and made himself a fixture on her ragged banks. Several years back, after a storied career guiding anglers on the world’s great rivers, Matt Breuer became manager of Ryabaga Camp on Russia’s Ponoi River. “After all,” Breuer told me over dinner, not long after inking his first contract with Ponoi River Company, “Only an asshole would try to catch an Atlantic salmon where there aren’t any.” His calculus was, and remains, irrefutable.

So in 2009, Breuer returned from a winter’s guiding in Tierra Del Fuego, made a whirlwind tour of friends’ couches and favorite barrooms, and borrowed my big blue duffel in preparation for a move to Russia. “I’ll get this back to you” he said, writing his name and address in eight-inch letters down the side of the bag; “and I’ll send some pictures too. By this time next week, I’ll have broken a rod on a twenty-pounder... just you wait and see.” The fact that I’d seen him break rods on six-inch brook trout was clearly a moot point. I dropped him off at JFK airport, where he disappeared into the queue at the check-in, and thereafter into the hinterlands of the eastern Kola Peninsula.

*

The Ponoi River, like its fish, is something of an enigma. It is a broad, shallow river of coppery water that rises in the sodden central Kola, well above the Arctic Circle. It cuts a ragged swath nearly due east through a vast uninhabited tundra, and at length empties into the White Sea. Each summer and fall, a tremendous run of Atlantic salmon enters the Ponoi and her major tributaries in order to spawn, and to lay waste to a longstanding angling falsehood. It is a fact that the average Ponoi angler lands, in an average week, more true salmon than many devotees catch in a lifetime, but such results do not come without a cost. It takes an effort nearly as prodigious as the fish’s own to monitor, nurture, and protect stocks in the Ponoi. It’s a rare jewel of a river in a supremely remote place, and a dedicated group of advocates has stopped at nothing to make it the most bountiful Atlantic salmon fishery in the world. That said, a very few anglers are lucky enough to fish it, and they do so at great expense. I have yet to hear of a dissatisfied customer.

In Breuer’s first season at Ryabaga, beneath the 24-hour daylight of the Arctic sun, he managed to break several rods on tail-walking salmon. None were behemoths, at least not in comparison to the fabled thirty-plus pounders of Norway’s Alta or Gaula, but among the numbers were some broad-shouldered brawlers pushing twenty. And he caught them in quantity. An email Breuer sent that first season was so riddled with vodka-induced syntax that it was nearly unreadable, at least all but the capitalized postscript. “CAUGHT TWELVE BEFORE LUNCH. 15 LB SMALLEST. WE GOTTA GIT YER ASS OVER HERE.”

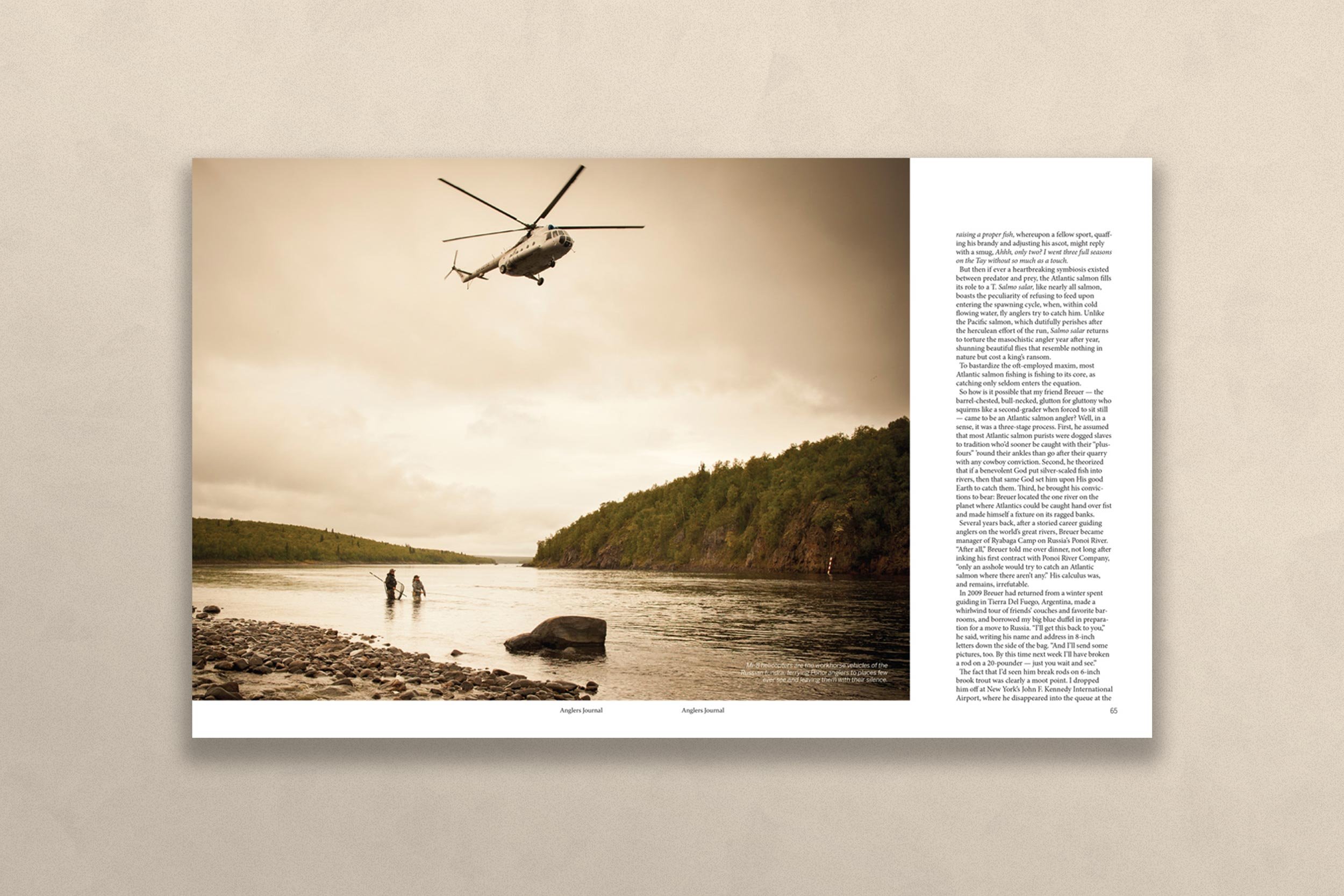

It took several years, but I finally made it, traversed the Atlantic in a FinnAir jet and the northern tier of Lapland in a rickety Mi8 helicopter with a fuel leak. Before the rotors quit turning, Matt Breuer shoved a tumbler of Russian Standard into one of my trembling hands, a 10 wt. Spey rod into the other, and bounced me down the camp steps towards the river. “I’m not much of a Spey caster yet…” I managed as Breuer slapped me on the back and the Vodka sloshed down my shirt front. “You think I’ve got it in me to land one of those silver beauties?” Breuer responded with characteristic eloquence. “Land one! Does a hobby horse have a hickory dick?” It appeared that the odds were in my favor.

Ryabaga is, first and foremost, a remote, wilderness fishing camp. Despite the world-class kitchen, opulent shower houses, and wireless internet service, anglers come to Ryabaga for the rare promise that they will, almost without question, tie into an abundance of Atlantic salmon. It was clear to me that very first afternoon, when Breuer hustled me through the Big Tent, filled a plate with reindeer salami, Stilton cheese, and cold-smoked salmon, and excitedly dragged me down to the moorage, encouraging the other guests not to dally. There were bright fish in the river, after all, and opportunities for food and cocktails when at length the sun dipped lower. I felt somehow that my physical body had outpaced my higher functions somewhere on the heli ride in, but Breuer was having none of it. He deposited me in the bow of a jet boat, tossed off the lines, and gunned upriver. What was left of my Russian Standard jounced out of my glass and disappeared in a fine, prismatic mist over the transom. “THAT WILL BE REFLECTED IN YOUR BILL!!!” Breuer shouted over the whine of the jet, and I couldn’t tell if he was serious.

He dropped anchor at the head of the long Home Pool, undid a bright tube fly on the rod he’d earlier handed me, and rigged up another for himself. “Now you get to catch a salmon,” he said by way of instruction, and in the descending silence, I had no option but to do just that.

*

The lower 42 miles of the Ponoi are owned by the Ponoi River Company, which in turn is owned by world-class angler Ilya Sherbovich. Ilya is a self-made man of epic proportion, whose gentle manner and humble presence belie a singleness of purpose. Upon acquiring the company and the best of the river, he set out to make Ryabaga a destination second to none. He fitted the camp with the finest amenities, and established a network of river guards to protect his waters from the rampant poaching that had long ago decimated the salmon rivers of the Kola. He spared no expense in establishing a program of scientific monitoring to maintain records of all bright fish entering, or re-entering, the Ponoi system. He then assembled the finest international guides and Spey casters in the world to serve on his team, under the management of my friend Breuer and company CEO Steve Estela. Unwilling to leave the slightest detail to question, Ilya committed himself to regular site checks, staff evaluations, and most importantly, hands-on assessment of fishery quality. The latter frequently requires that Ilya’s hands be on a Spey rod, often deeply bent against the pull of a spunky salmon. Such quality control measures seem to suit Ilya just fine. To date, I don’t know that anyone more appreciates the richness of the Ponoi, or works harder in the spirit of its conservation, than Ilya Sherbovich himself.

On that first night, swinging tubes across the head of the Home Pool, I was struck by just how far I felt from my own home. The Kola is a raw and rugged place that appears newly hatched and scrubbed bare. Buzzards and ravens spin overhead in a thin-air sky, and the river glides with epic patience, broken only at points by jutting boulders. Across the width of it, which nears 500 feet, the subtle presence of structure is not at first apparent. “Hit the windows and the seams” Breuer kept telling me, pointing to glassy spots that materialized, became obvious, and then quickly braided themselves back into the weave of the current. I did my best to swing my fly through the likeliest spots, but in the end it didn’t really matter. Untangling a rat’s nest in my running line, my first Ponoi fish nearly jerked the rod from under my arm, and I became fast to something big and strong and going away. “Trout” said Breuer shaking his head. “Jerk the line hard and he’ll come off.”

“Are you kidding me?” I worked the fish in, and Breuer hand landed the biggest trout of my life, a sea-run brown of 5 or so pounds.

“Strip a little next time or you’ll be dinking around with those things all day.”

Out across the current a big, sparkling fish breached, cart-wheeling into a slow-setting sun.

Breuer pointed. “That’s what we’re after. But if you’re gonna stand there with your mouth hanging open, I’ll cover that piece of water for you from here.”

Before the night was through, I’d landed two ‘proper’ salmon of over ten pounds. They did all the things I’d been told they would do. There were blistering runs and tail-standing acrobatics and sullen, head-shaking sulks. With the second fish to net, Breuer slapped me on the back and said it was time for the hallowed ‘first night dinner’ at which he was a fixture. “You got your first salmon out of the way,” he said happily, and I just sat down and tried to make sense of this big barren place in which a coppery river was bursting with fish.

The rest of my Ponoi week followed suit. There was a slow but steady climb towards proficiency as a Spey caster, and fish that took hard and wouldn’t stick. There was the slab of a fifteen-pounder that attacked a trailed fly just behind the outboard while I relieved myself to leeward, and the nine-pounder that smoked my reel and took backing off the spool that had never seen the light of day. There was the morning when, casting to river right from the bow of the boat, I became helplessly tangled trying to cover a big fish that showed twice, just off the bank. Pulling loops of Scandi-head from around my ankles, my dear friend Breuer, who’d been fishing river left, turned an abrupt about-face and shot a snap-t just upstream of my fish.

“Only an asshole would let a fish such as that miss the opportunity of being introduced to me,” declaimed Breuer, stripping his fly through the holding water. He stuck the fish of course, and brought to net a glorious, bright buck that pushed eighteen pounds. “Only a what?” said guide Pat Brennan under his breath, and I think even Breuer felt a little bit bad for poaching the biggest fish of the week.

In the end, the Ponoi River was something of a revelation. There was vodka of course, and the finest cuisine, and friendship and laughter and stories. There was the chance to hob-knob with angling elite: the fraternity of international anglers, after all, occupies some pretty rarified air. There was even the presence of a heightened awareness that the experience alone was, for me anyway, an opportunity of such far-flung rarity that I couldn’t help but embrace it wholeheartedly. But at root it was all about the fish. These fish, these rare and beautiful fish that I’d always considered scarcer than hen’s teeth were, at the start of each day, a foregone conclusion. On Ponoi, it’s not about whether salmon will be caught, it’s about ‘when’ and ‘how many’ and whether the guide will be able to weigh and release one fish fast enough to get his net under another. It’s actually that good.

On the final day, with a low ceiling dropping in and the heli pilots champing for a departure, Matt Breuer escorted me to the pad. He slapped me on the back and tousled my hair and appeared, in his indomitable way, a little bit sad to see me go. We shook hands, and as he chucked my duffel (with his name and address still inked on the side) up into the cabin, he offered these parting thoughts:

“Only and asshole” said my friend Matt Breuer, “would land a situation this good and forget to share it with his best friend,” to which I had no response. But if I ever hit the lottery, or win a Pulitzer, or find a twelve pack of Pabst in my fridge that needs finishing, Breuer will be my first call.

Had I the means, I’d sponsor him a week on the world’s finest Atlantic salmon river; but then of course, I’d be the asshole. He’d already be there.

Postscript

After several years living, guiding, and fishing on Ponoi, Matt Breuer returned to the waters of Montana, where he rows a boat through the heat of summer on the Madison, Yellowstone, and Firehole rivers. Spoiled by his years in Russia, a 5 lb. Montana brown now commands little more than a shrug from Breuer, who offsets his small fish months with winters spent in British Guyana. There he guides for Arapaima, the world’s largest freshwater species of scaled fish, in the tepid jungle waters of the Rewa and Rupununi watersheds. A bit of his heart, however, remains fixed in the eastern Kola, where his legacy, and his conviction in the Ponoi, live on.

First published Anglers Journal