River of No Return

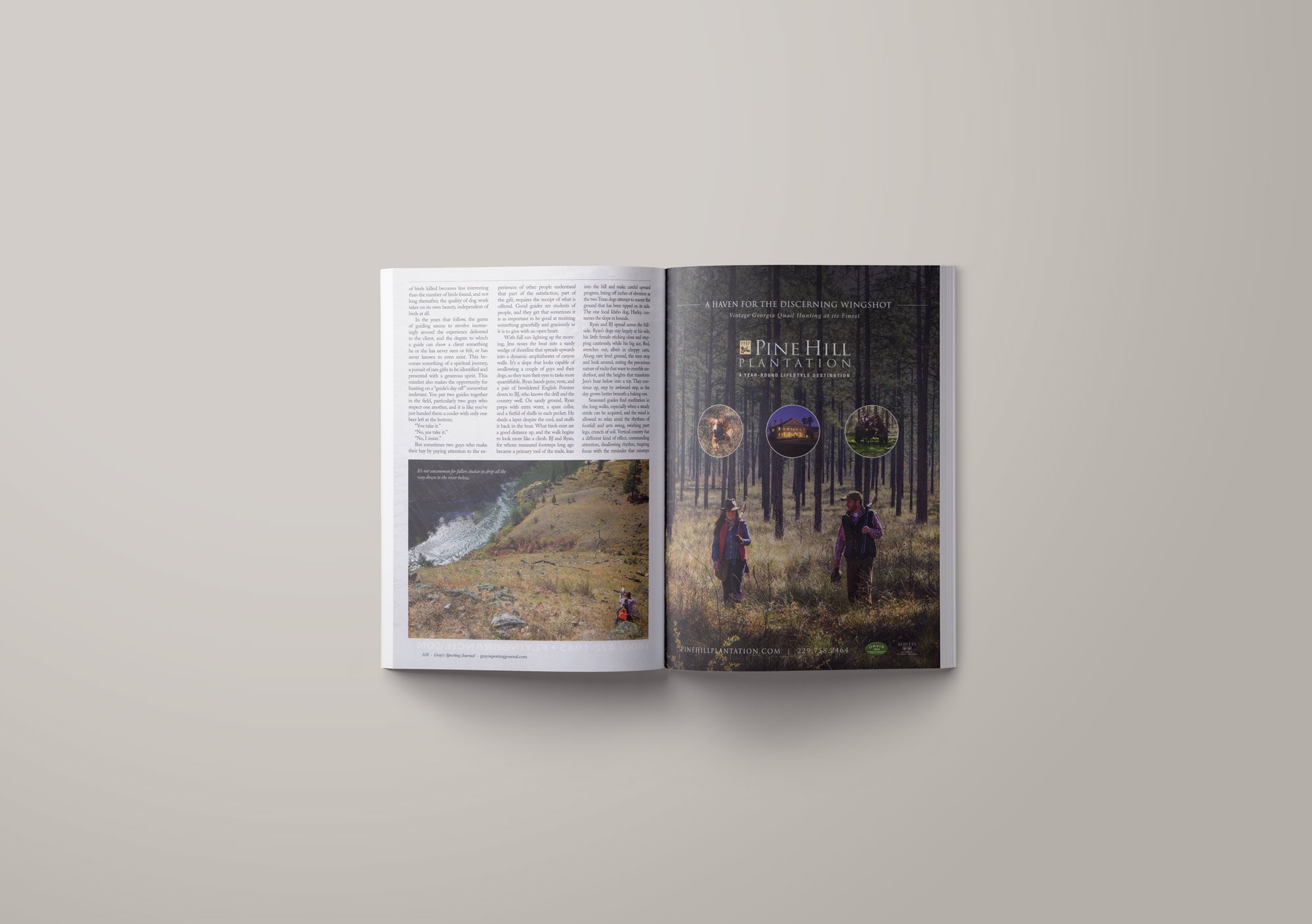

On an October morning, a small group of hunters unloads gear at the Vinegar Creek boat ramp. The ramp is quiet, what with most of the summer traffic gone, and the steelhead returns in downward trend from their historic heights. The ramp’s disappearance into the Main Salmon River marks the literal end of the road, a term which may over-sell the bumpy to-and-from that connects the Idaho town of Riggins with several million untracked acres of timber, rock, and sparest grassland known as the Frank Church – River of No Return Wilderness. The remaining journey into the heart of the place will be by boat, the only real means of conveyance through the canyons and sidehills that rise emphatically from the riverbed. Beside the rush of water, the hunters place gun cases and dog crates and lug-soled boots in piles, taking a rough inventory, getting things sorted. After some consideration, they begin separating excess and redundancy from bare necessity, putting the former back in the truck. Jet boats are small, and dog crates take up lots of space; nothing like a few days in hard-to-get-to country to help trim the fat, real and metaphoric.

With gear assembled, the group stands at the river’s edge and looks upstream. With no real job to do other than watch a river slide past, the enormity of the country opens up into a tableau that seems somehow to defy scale. From the ropy flat of water, walls of rock soar upward like skyscrapers, making access and egress feel unlikely, making the “River of no Return” denomination somewhat more apt. Here, where it passes by the Vinegar Creek ramp, the Main Salmon is in its full glory. It has fallen several thousands of feet from its headwaters near Galena summit and acquired the South Fork of the Salmon along its way. Bolstered by its many tributaries, made limber by a hundred sinewy miles of twists and rapids, the river gathers a head of steam above Vinegar Creek and takes a no-nonsense look west. It is a mighty piece of water at this point, done playing games. In the battle of wills between mountains and water, the river leverages its strength and bores down with such force as to shove Idaho’s bedrock out of the way, pushing it off into the scrub desert in a straight shot all the way to Riggins. Looking upstream into the maw of something like that, a small group of hunters might wonder whether they are welcome here at all, whether upon entry the place will simply grind them back into dust and spray and echoes.

The hunters stand and consider the weight of a river. Among them, BJ Walle and Ryan O’Shaughnessy look over the dog crates and discuss the events to come. Both men are professional bird guides who spend their days steering clients through lean, rough country, BJ in the nearby Clearwater drainage, and Ryan in Far West Texas. Both have come to believe that wild birds are designed to congregate in beautiful places, and that beautiful places, and the wild birds they play host to, are designed to humble a person. That is why they are here. For BJ and Ryan, chukars are just an excuse, a reason to look and listen closely, to get bruised and bloodied a little, and to be made to feel small. There is some intrinsic satisfaction found here, tangled up in the cacti and scree.

That the river pushed past with indomitable weight, that the banks rise like fortress walls… well, to guys Ryan and BJ, that just proves the place holds something the universe deemed worthy of protecting.

*

BJ sits in the back of the jetboat as captain Jess Baugh picks his way upstream. BJ and Jess go way back. They met in June of ’97, and worked a decade of summers guiding whitewater trips through the 78 miles of the Salmon that meander through the Frank Church Wilderness. BJ put in sixty or so trips before moving over to Kamiah to focus on his bird guiding career, and Jess stayed behind in Riggins, eventually becoming the outfitter for his own company, Salmon River Tours. He spends his year guiding anglers and bird hunters up and down The River of No Return, and, alongside wife Brenda running the Ram House Lodge on Mackay Bar. He affords BJ a standing invitation, and despite BJ’s best intentions, and all irony aside, return ventures to this place are precious and few.

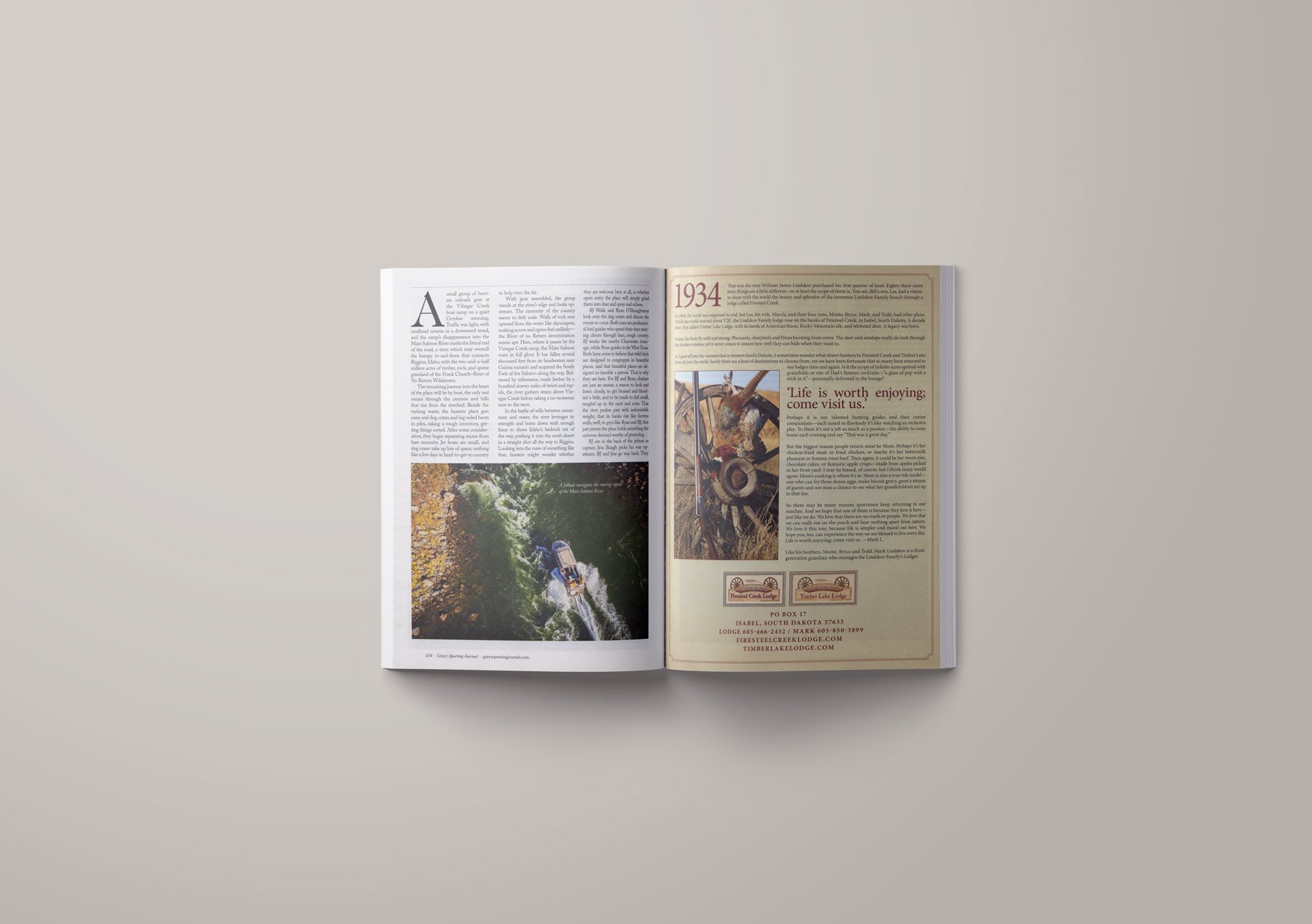

The physics at play on the run upstream are somewhat disconcerting, so BJ opts not to. He keeps his eyes on the shoreline, looking for chukars loafing in the advancing sun, giving themselves up with a flip of wing. Small details get lost easily in those walls of rock and shadow. Jess’s jetboat, despite its load of hunters and dogs and gear, moves definitively across a plane of water that continues to slide downstream past a cobbled riverbed. Making steady headway upstream and to the east, Jess pilots the boat against the grain of the river and over the self-same riverbed, albeit in an opposite direction. With subtle corrections for left and right, he moves through a labyrinth of fixed obstacles made dynamic by propelled boats and falling water. He dodges boulders and slips through sluiceways, ferrying the group upstream. Twenty-two river miles up from Vinegar Creek, Jess hauls the boat into some slack below his outpost lodge and kills the engine. He helps the group unload: bird dogs and guns and boots, the necessities and few of the niceties save some preferred booze and beer, all plunked down in the middle of remotest Idaho.

It has rained through the preceding days, and over drinks around the fire, BJ and Jess discuss the implications of more water scattered through the system, and persistent chilly weather. Water will have pushed the birds higher, a thousand feet higher as a rule, and locating them with precision will be a challenge. The birds will not need to congregate at the water’s edge as they generally do, skittering through the low-lying rocks and calling as the sun hits them and warms them up. In a normal day’s chukar hunting along the Salmon, hunters slip downstream by raft or jetboat, idly fishing for steelhead and trout but keeping an eye peeled for movement, an ear peeled for the “chuck-chuck-churrruck-chuck” that belies the presence of birds. Once birds are located, the boat deposits hunters (and dogs ideally) on shore, whereupon the covey is pointed or busted, and shots echo through the canyons, and birds occasionally fall all the way into the river itself. Hunters can follow the scattered singles and pairs as high as lungs and legs allow, though in a good year, knots of fifteen or twenty birds appear every half mile or so, and the high-flyers are largely left for seed. But unseasonable rain in advance of a trip muddies all sorts of waters, and it seems the hunters will have some bird finding to do in the morning.

*

Career bird guides are a curious lot. The sample size of folks who have spent a decade or more putting folks onto wild birds is quite small, so generalizations are hard to come by, and quite possibly statistically inconclusive. That said, BJ and Ryan, and folks whose guide careers can be counted in thousands of days, seem to share a common evolutionary arc. It seems that inside of the first few seasons the number of birds killed become less interesting than the number of birds found, and not long thereafter, the quality of dog work takes on its own beauty, independent of birds at all. In the years or decades that follow, the game of guiding seems to revolve increasingly around the experience delivered to the client, and the degree to which a guide can show a client something he or she has never seen or felt, or has never known to even exist. This becomes something of a spiritual journey, a pursuit of rare gifts to be identified, curated, and presented with a generous spirit, and this mindset ironically makes the opportunity for hunting on a “guide’s day off” somewhat irrelevant. You put two guides together in the field, particularly two guys who respect the other and the experience unfolding, and it is like you’ve just handed them a cooler with only one beer left at the bottom:

“You take it…”

“No YOU take it…”

“No, I insist…” they seem to say, each looking for the chance to better the other’s experience around each bend. It’s a sight to see.

But sometimes two guys who make their hay by paying attention to other peoples’ experiences understand that part of the satisfaction, part of the gift, requires the receipt of what is offered. Giving becomes a part of the craft and receiving does too. Good guides are students of people, and they get that sometimes it is important to be as good as receiving something gracefully and graciously as giving with an open heart.

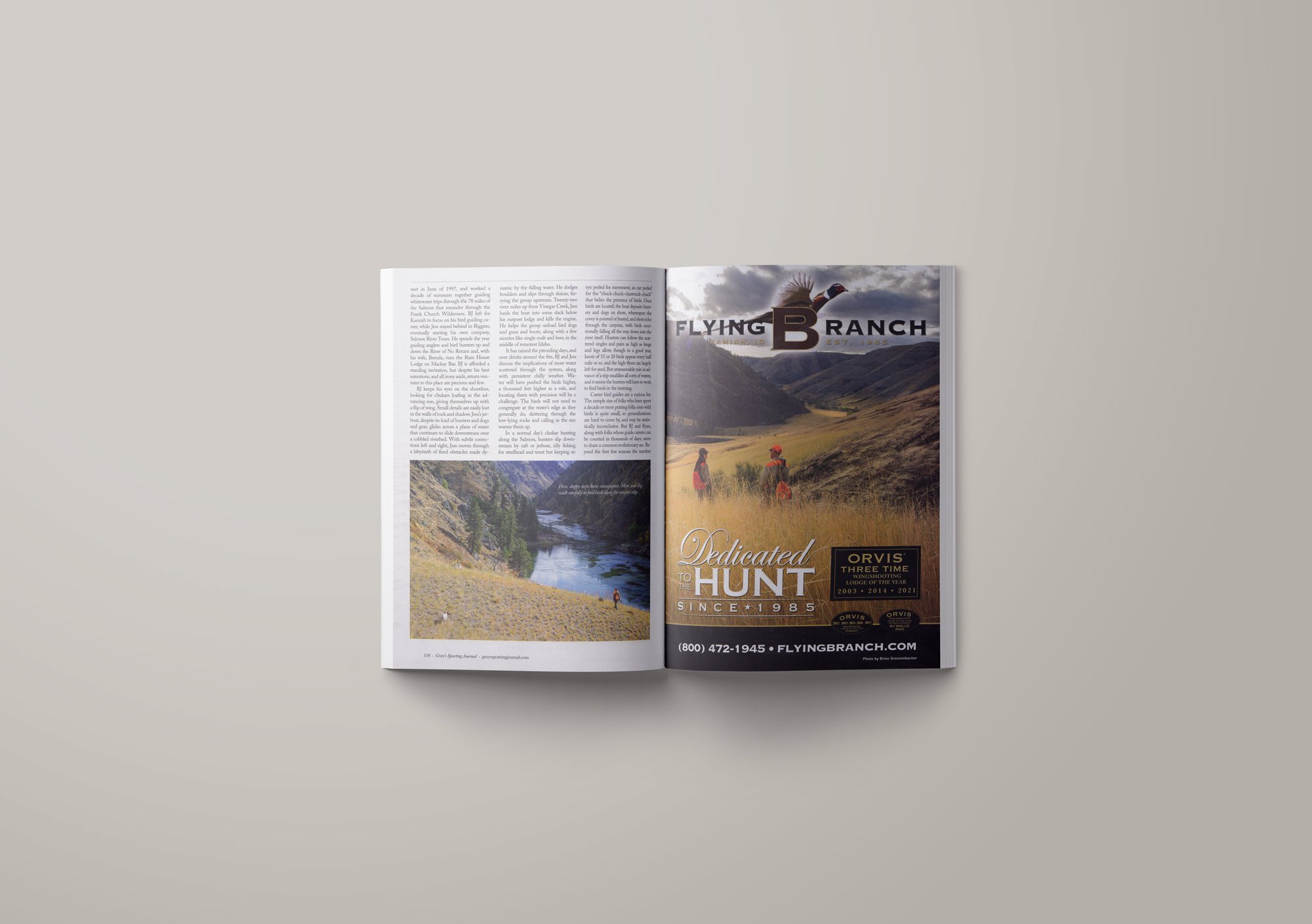

With full sun lighting up the canyon walls, Jess noses the boat up into a sandy wedge of shoreline that spreads upwards into an amphitheater of sorts. It’s a slope that looks capable of swallowing a couple guys and their dogs, so they turn their eyes to tasks more quantifiable. Ryan hands guns, vests, and a pair of bewildered English Pointers down to BJ, who knows this drill and this country well. On sandy ground, Ryan takes his cues: extra water, a spare collar, a fistful of shells in the pockets. He sheds a layer despite the cool, and stuffs it back in the boat. What birds exist are a good distance up, and the walk begins to look more like a climb as the immediacy of the canyon walls looms. BJ and Ryan, for whom measured footsteps long ago became a primary tool of the trade, lean into the hill and make careful upward progress, biting off inches of elevation as the two Texas dogs attempt to learn about flat ground that has been tipped on its side. The one local Idaho dog, Harley, consumes the slope in bounds.

Ryan and BJ spread out across the hillside. Ryan’s dogs stay largely on his side, his little female sticking close and stepping cautiously, his big ace dog Red stretching out, albeit in choppy casts. At the rare few incidences of level ground, the men stop and look around, noting the precarious nature of rocks that want to crumble out from underfoot, and the heights that change Jess’s boat into a toy. The river slips on, and the slope persists, so they continue up, step by awkward step, the day growing hotter as the sun gains the top of its arc.

Seasoned guides find a meditation in the long walks, especially when a stride can be acquired, and the mind is allowed to relax. The rhythms of footfall and arm swing, swishing pant legs, crunch of soil. Vertical country has a different kind of effect, commanding attention, disallowing any rhythm, tinging focus with the tachycardic reminder that missteps have real consequences. Ryan watches Red with some pride as he stretches out with increasing confidence, seemingly making sense of this steep new world. He watches Red become engrossed by something, a lizard most likely. The dog quickens his pace and takes a reckless turn around an arete… and falls. He’d later say it was like something in an old Loony Toons reel, wherein Red committed, realized he had gone off the edge, looked down, looked back, looked down again, and started paddling his feet through an expanse of open air.

Ryan steps up to see Red rolling down a scree slope some forty feel below, and assumes him broken. He starts giving back reckless vertical steps as quickly as he can, dropping down to Red’s level, but losing sight of him. He makes his way around the knife-edge and finds Red much flustered by his fall, but standing on four feet, slowly making sense of his downward journey. As you do, Ryan checks him over, and BJ comes around and into sight, having heard the commotion. The three sit there for a moment to let heartrates normalize and assess the injured, who seems to have come through it unscathed. And wouldn’t you know, just then a small covey of birds breaks away from the slope below, takes a hard swing against the hill, and lights in a clump of brush on the skyline. They may well have been conjured from that slope just to brighten the mood, and they did wonders for Red’s outlook. 100 yards up and across the slope waited the closest thing to a slam dunk the guys had seen yet.

BJ turned to Ryan. “You good?”

He shook his head.

“Look, you’ve come a long way. Where is the best place for you to ensure you have the shot you want?”

Ryan was getting to his feet. “You sure about that?” he asked.

“Absolutely.”

“Well, in that case I’ll come in on top with the dogs.”

“Yep,” said BJ. “That sounds about right…”

The fellows and the dogs spread out across the slope, and Ryan picks his way back up to level with the birds and above. The dogs move slowly into a favorable wind, and thoughts of lizards are subsumed by the pungency of wild birds near at hand. Ryan creeps up. Red takes another cautious step, and three hard-earned Idaho chukars execute three wingbeats each, pause, and dip, entering their swooping descent just as Ryan takes a poke and tumbles one bird, which goes limp in the air and dies before it hits the scree. An outside bird bends back in against the contour and BJ dings him too, and in a cartwheel of feathers he comes to rest a good hundred yards below.

The whoops that ring out bounce across the canyon and back again, amplified by the walls of the big bowl of rock, defying the vacuity of the space. Shared enthusiasm calls out clean and clear and redoubles itself, and one guy from Far West Texas wholeheartedly appreciates one guy from the Clearwater Valley, and the feeling is mutual, as is the common appreciation for this place. And they both look down and realize yet again how big and hard and emphatic a landscape they are standing in, and how impossibly possible it might be to summon a pair of masked birds out of all that space and time.

Thinking these things, legs a little wobbly, they take cautious steps down, down, down, and pick up their dinner on the way.

If You Go

The Frank Church – River of No Return Wilderness is comprised of nearly 2.5 million rugged, ragged acres in central Idaho. Access to the wilderness is best accomplished by boat, with the Main and Middle Forks of the Salmon River serving as primary throughfares. With access limited and recreational use contingent on permits, most visitors rely on an experienced outfitter to help maximize a visit to the Frank Church. Jess and Brenda Baugh operate Salmon River Tours and provide lodging at a wilderness inholding on Mackay Bar on the Main Salmon. Small, private groups can be lodged and fed at the Ram House Lodge, and from that foothold can hunt the region’s wild chukar, Hungarian partridge, and California Valley quail through the remote canyons. Dogs can be provided, or guests can bring their own, and hunting can be fully guided. Supplemental activities include fly fishing, either with conventional or fly tackle, for the storied Salmon River steelhead. Fly into Boise or Lewiston, Idaho and access the river via the Vinegar Creek Ramp, approximately an hour and a half drive east of Riggins. For more information contact Salmon River Tours/Jess or Brenda Baugh at 1-888-893-2820 or via email at salmonrivertours@gmail.com . More information available at www.salmonrivertour.com

First Published in Gray’s Sporting Journal