Real Sound River Sound

When I was young and impressionable, I got served by a brown trout on the Gunnison River. It happened downstream from the Black Canyon, in that place outside Hotchkiss, CO where things open up and stretch out and the river looks like a boulevard of clover honey. The trout in question thumped a black wooly bugger so hard that, had the tippet held, the hook-set would have crossed his eyes. I felt him for a second, felt the scale of his downstream lunge, then the ping and snap of the mono. My line hung limp in the current and a tiny piece of me died just then, so I waded to the bank to sit and sulk. It’s a response I favor to this day, though my leader knots are better, and my failures minutely less frequent.

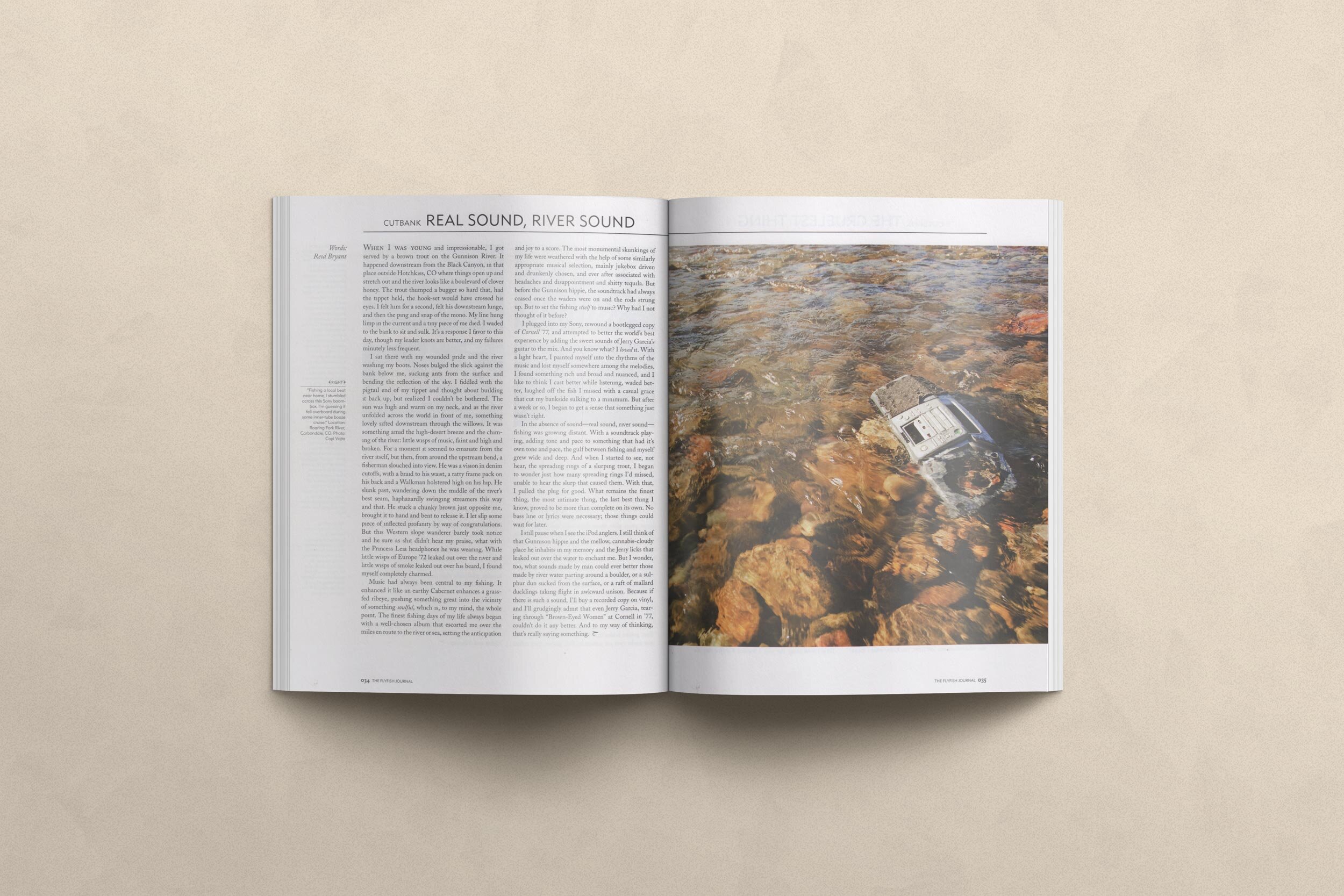

I sat there with my wounded pride and let the river wash my boots. Noses bulged the slick against the bank below me, sucking ants from the surface and bending the reflection of the sky. I fiddled with the pigtail end of my tippet and thought about building it back up, but realized I couldn’t be bothered. The sun was high and warm on my neck, and as the river unfolded across the world in front of me, something lovely sifted downstream through the willows. It was something in amidst the high-desert breeze and the chiming of the river: little wisps of music, faint and high and broken. For a moment it seemed to emanate from the river itself, but then, from around the upstream bend, a fisherman slouched into view. He was a vision in denim cutoffs, with a braid to his waist, a ratty frame pack on his back and a Walkman holstered high on his hip. He slunk past, wandering dead down the middle of the river’s best seam, haphazardly swinging streamers this way and that. He stuck a chunky brown just opposite me, brought it to hand and bent to release it, and I let slip some piece of inflected profanity by way of congratulations. But this Western slope wanderer barely took notice, and he sure as shit didn’t hear my praise, what with the Princess Leah headphones he was wearing. While little wisps of Europe ‘72 leaked out over the river and little wisps of smoke leaked out over his beard, I found myself completely charmed.

Music had always been central to my fishing. It enhanced it like an earthy Cabernet enhances a grass-fed ribeye, pushing something great into the vicinity of something soulful, which is, to my mind, the whole point. The finest fishing days of my life always began with a well-chosen album that escorted me over the miles en route to the river or sea, setting the anticipation and joy to a score. The most monumental skunkings of my life were weathered with the help of some similarly appropriate musical selection, mainly jukebox driven and drunkenly picked, and ever after associated with headaches and disappointment and shitty tequila. But before the Gunnison hippy, the soundtrack had always ceased once the waders were on and the rods strung up. But to set the fishing itself to music? Why had I not thought of it before?

So I took a page from his book, and, as Tim Leary put it, I turned on, tuned in, and dropped out. I tried to augment the truest, cleanest, most connected experience that I know with a layer of extra texture. I plugged in to my Sony, re-wound a bootlegged copy of ‘Cornell ‘77’, and attempted to better the world’s best experience by adding the sweet sounds of Jerry Garcia’s guitar to the mix. And you know what? I LOVED it. With a light heart, I painted myself into the rhythms of the music, and lost myself somewhere among the melodies. In there I found something rich and broad and nuanced, and I like to think I cast better while listening, waded better, laughed off the fish I missed with a casual grace that cut my bank-side sulking to a minimum. But after a week or so of the same, I began to get a sense that something just wasn’t right.

In the absence of sound -- real sound, river sound -- my fishing was growing distant. With a soundtrack playing, adding tone and pace to something that had it’s own tone and pace, the gulf between my fishing and me grew wide and deep. And when I started to see, not hear, the spreading rings of a slurping trout, I began to wonder just how many spreading rings I’d missed, unable to hear the slurp that caused them. With that I pulled the plug for good, and got the hell off the bus. What remains the finest thing, the most intimate thing, the last best thing I know proved more than complete on it’s own. No bass line or lyrics were necessary; those things could wait for later.

I’m older now, but I still pause when I see the Ipod anglers, as I remember my days as one of them. I still think of that Gunnison hippie, and the mellow, cannabis-cloudy place he inhabits in my memory, and the Jerry licks that leaked out over the water to so enchant me. But I wonder too what sounds made by man could ever better those made by river water parting around a boulder, or a sulphur dun sucked from the surface, or a raft of mallard ducklings taking flight in awkward unison. Because if there is such a sound, I’ll buy a recorded copy on vinyl, and I’ll grudgingly admit that even Jerry Garcia, tearing through ‘Brown Eyed Women’ at Cornell in ’77, couldn’t do it any better. And to my way of thinking, that’s really saying something.

First published in Flyfish Journal