Perspective

“It is a narrow mind which cannot look at a subject from various points of view.”

On a gloomy morning years ago, my father took me for a walk in the mountains. I was little at the time and made a point of pulling fistfuls of wet ferns from the meadow edge, slopping through puddles at the trailhead as I followed my dad into the spruces. We plunked along at what must have been a snail’s pace, stopping here and there to look about. My father was never one to say a whole lot, and we shared a familiar silence; lazy switchbacks traced a path over boulders and tree roots, and I recall an awareness of slow upward progress, and the abstract understanding that my little self was situated somewhere on a wooded piece of the New England skyline, the contours of which I had before only seen from a distance. We plunked along, silent and slow, navigating light filtered through branches. Our morning’s passage has become one of those childhood memories made up of fragments, sentiments that are sepia-tinted and nostalgic, like so many things I treasure.

We walked for maybe an hour. At some point the trail rolled over and leveled off, steering us onto a ledge of rock beneath the pinnacle. My father and I headed out on this shoulder to get a view. Around us the world opened up: fog hung gauzy between the ridges, and the village from which we’d come was obscured completely, nowhere to be seen. I remember wondering at this and remarking to my father that the fog banks far below us looked just like clouds.

“But they are clouds…” he said in his gentle but matter-of-fact sort of way. “The difference is you… you are used to looking up at clouds from underneath, and now you’re seeing what they look like from a different point of view.”

I thought for a minute about my father’s tidy explanation, and it gave me an uncomfortable feeling. It seemed to me that I’d somehow snuck a glimpse of something that I wasn’t really supposed to see. I looked at my father; despite his calculus, I couldn’t help but see clouds from above as something altogether different from the ones I’d known from underneath, and that realization, more even than the height or the long walk into the forest, made matters a little bit uncertain. As I recall, we never finished the hike to the tippity-top, opting instead to head back into the trees, where dimensions sorted themselves out in broken light and birdsong, and the smell of spruce needles and popple sap was a comfort.

*

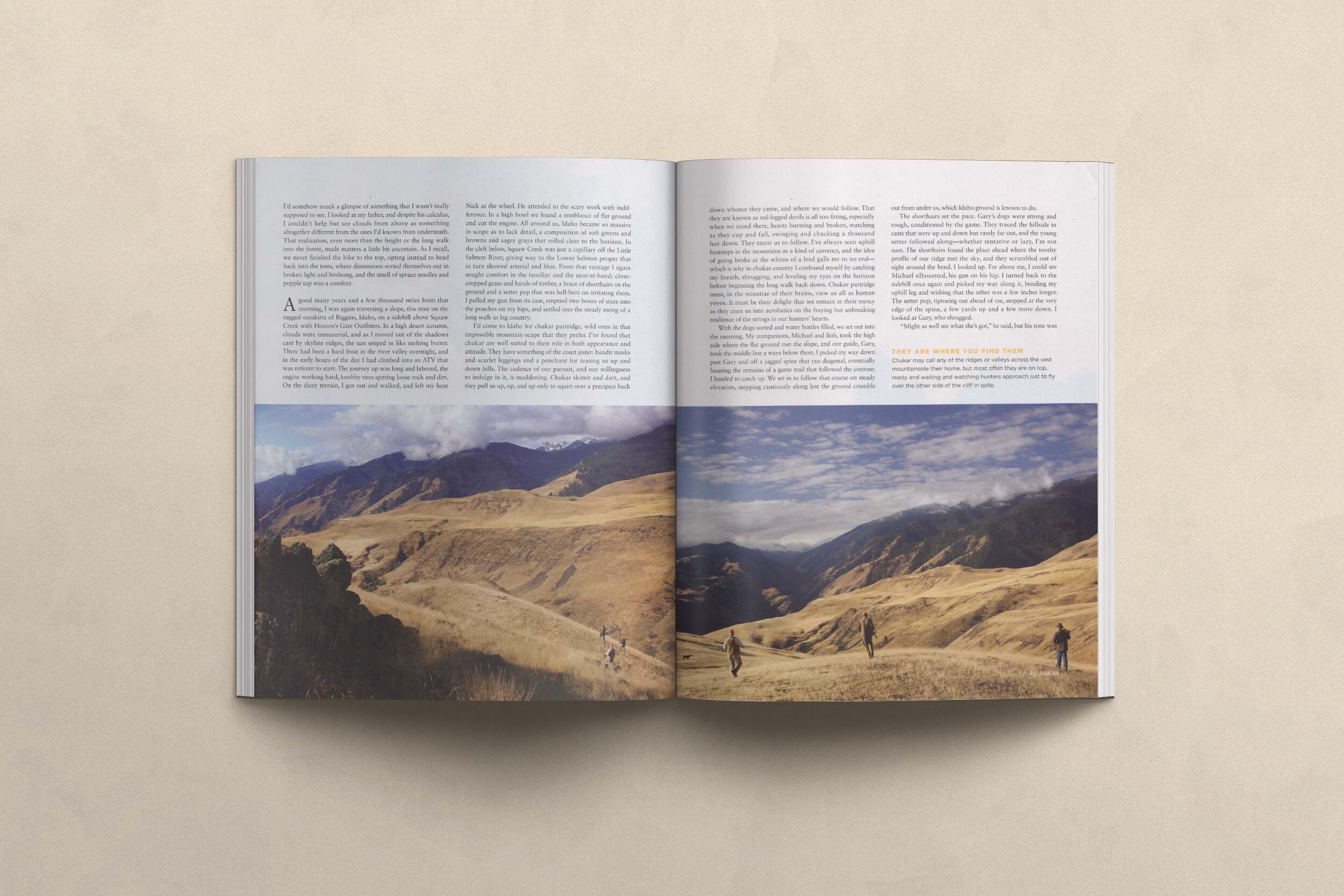

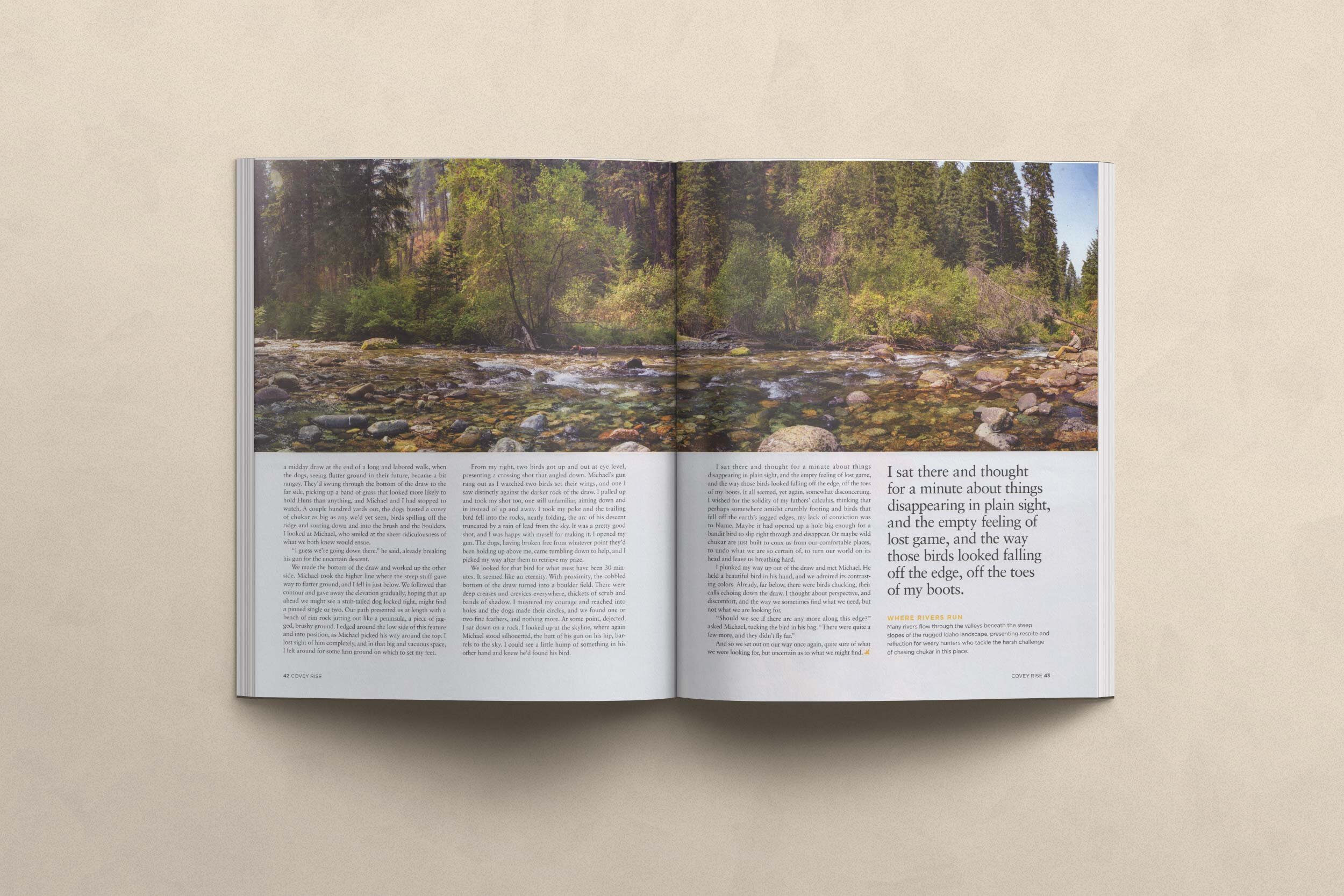

A good many years and a few thousand miles from that morning, I was again traversing a slope, this time on the rugged outskirts of Riggins, Idaho, on a side-hill above Squaw Creek. In a high desert autumn, clouds were immaterial, and as I moved out of the shadows cast by skyline ridges, the sun seeped in like melting butter. There had been a hard frost in the river valley overnight, and in the early hours of the day I had climbed into an ATV that was reticent to start. The journey up was long and labored, the engine working hard, knobby tires spitting loose rock and dirt. On the really dicey terrain I got out and walked, and left my host Nick at the wheel. He attended to the scary work with indifference. In a high bowl we found a semblance of flat ground and cut the engine. All around us, Idaho became so massive in scope as to lack detail, a composition of soft greens and browns and sagey grays that rolled clear to the horizon. In the cleft below, Squaw Creek was just a capillary off the Little Salmon River, giving way to the Lower Salmon proper that in turn showed arterial and blue. From that vantage I again sought comfort in the familiar and the near-at-hand: close-cropped grass and bands of timber, a brace of shorthairs on the ground and a setter pup that was hell-bent on irritating them. I pulled my gun from its case, emptied two boxes of sixes into the pouches on my hips, and settled into the steady swing of a long walk in big country.

I’d come to Idaho for chukar partridge, wild ones in that impossible mountain-scape that they prefer. I’ve found that chukars are well suited to their role in both appearance and attitude. They have something of the court jester: bandit masks and scarlet leggings and a penchant for teasing us up and down hills. The cadence of our pursuit, and our willingness to indulge in it, is maddening. Chukars skitter and they dart, and they pull us up, up, and up only to watch them squirt over a precipice back down whence they came, and whence we followed. That they are known as red-legged devils is all too fitting, especially when we stand there, hearts bursting and broken, watching as they cup and fall, swinging and chucking a thousand feet down. They taunt us to follow. I’ve always seen uphill footsteps in the mountains as a kind of currency, and the idea of going broke at the whims of a bird galls me to no end. Which is why in chukar country I confound myself by catching my breath, shrugging and leveling my eyes on the horizon before beginning the long walk back down. Chukar partridge must, in the minutiae of their brains, view us all as human yoyo’s. It must be their delight that we remain at their mercy as they coax us into acrobatics on the fraying but unbreaking resilience of the strings in our hunters’ hearts.

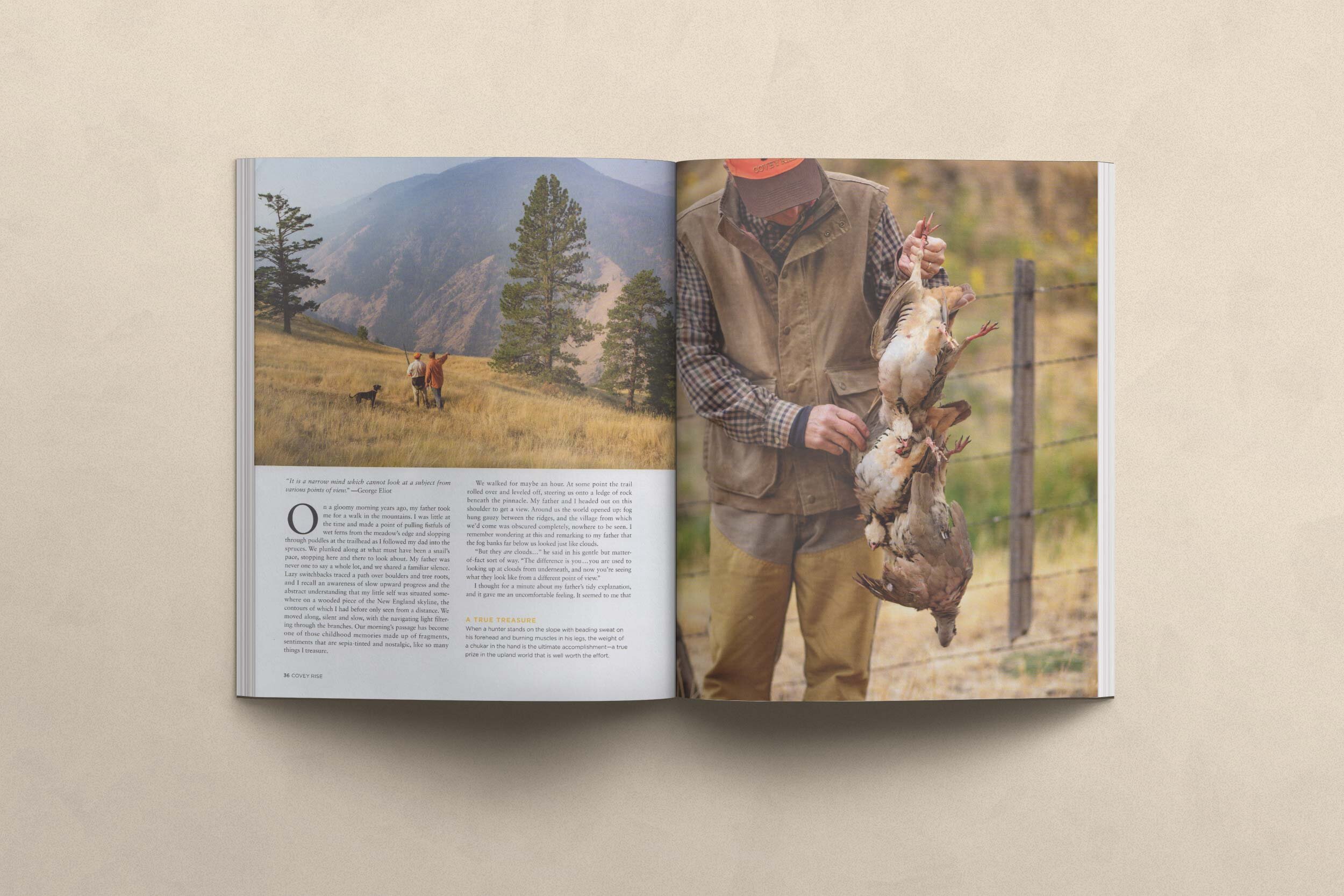

With the dogs sorted and water bottles filled, we set out into the morning. My companions Michael and Bob took the high side where the flat ground met the slope, and our guide Gary took the middle line a way below them. I picked my way down past Gary and off a jagged spine that ran diagonal, eventually locating the remains of a game trail that followed the contour. I hustled to catch up. We set in to follow that course on steady elevation, stepping cautiously along lest the ground crumble out from under us, which Idaho ground is known to do.

The shorthairs set the pace. Gary’s dogs were strong and tough, conditioned by the game; they traced the hillside in casts that were up and down but rarely far out, and the young setter followed along, whether tentative or lazy I’m not sure. The shorthairs found the place ahead where the toothy profile of our ridge met the sky, and they scrambled out of sight around the bend. I looked up. Far above me, I could see Michael silhouetted, his gun on his hip. I turned back to the sidehill once again, and picked my way along it, bending my uphill leg and wishing that the other was a few inches longer. The setter pup, tiptoeing out ahead of me, stopped at the very edge of the spine, a few yards up and a few more down. I looked at Gary, who shrugged.

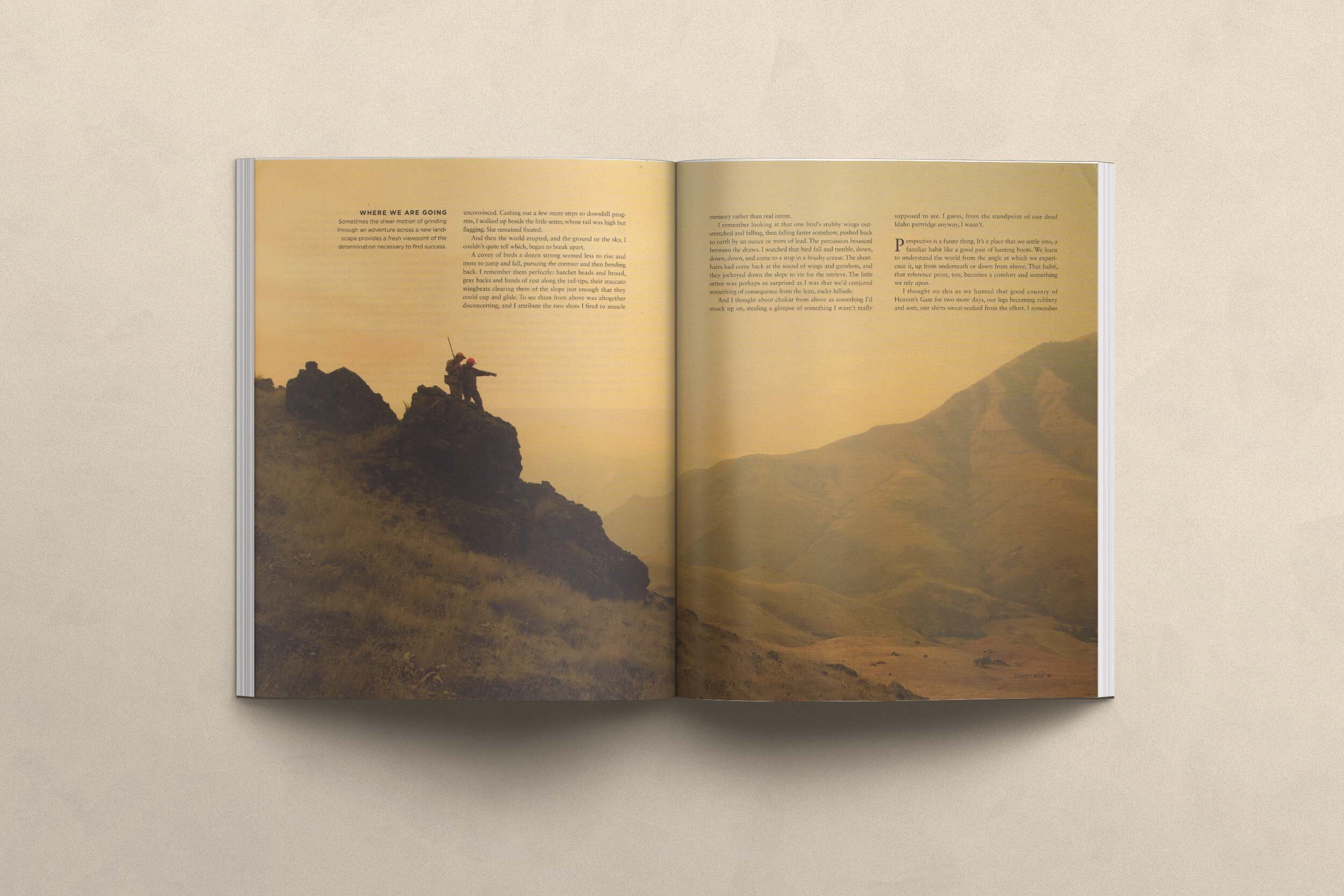

“Might as well see what she’s got…” he said, but his tone was unconvinced. Cashing out a few more steps to downhill progress, I walked up beside the little setter, whose tail was high but flagging. She remained fixated.

And then the world erupted, and the ground or the sky, I couldn’t quite tell which, began to break apart.

A covey of birds a dozen strong seemed less to rise and more to jump and fall, pursuing the contour and then bending back. I remember them perfectly: hatchet heads and broad gray backs and bands of rust along the tail-tips, their staccato wingbeats clearing them of the slope just enough that they could cup and glide. To see them from above was altogether disconcerting, and I attribute the two shots I fired to muscle memory rather than real intent. I remember looking at that one bird’s stubby wings outstretched and falling, then falling faster somehow, pushed back to earth by an ounce or more of lead. The percussion bounced between the draws. I watched that bird fall and tumble, down, down, down, and come to a stop in a brushy crease. The shorthairs had come back at the sound of wings and gunshots, and they jockeyed down the slope to vie for the retrieve. The little setter was perhaps as surprised as I was that we’d conjured something of consequence from the lean, rocky hillside.

And I thought about chukars from above as something I’d snuck up on, stealing a glimpse of something I wasn’t really supposed to see. I guess, from the standpoint of one dead Idaho partridge anyway, I wasn’t.

*

Perspective is a funny thing. It’s a place that we settle into, a familiar habit like a good pair of hunting boots. We learn to understand the world from the angle at which we experience it, up from underneath or down from above. That habit, that reference point, it too becomes a comfort, and something we rely on.

I thought on this as we hunted that good country for two more days, our legs becoming rubbery and sore, our shirts sweat-soaked from the effort. I remember a midday draw at the end of a long and labored walk, when the dogs, seeing flatter ground in their future, became a bit rangey. They’d swung through the bottom of the draw to the far side, picking up a band of grass that looked more likely to hold huns than anything, and Michael and I had stopped to watch. A couple hundred yards out, the dogs busted a covey of chukars as big as any we’d yet seen, birds spilling off the ridge and soaring down and into the brush and the boulders. I looked at Michael, who smiled at the sheer ridiculousness of what we both knew would ensue.

“I guess we’re going down there…” he said, already breaking his gun for the uncertain descent.

We made the bottom of the draw and worked up the other side. Michael took the higher line where the steep stuff gave way to flatter ground, and I fell in just below. We followed that contour and gave away the elevation gradually, hoping that up ahead we might see a stub-tailed dog locked tight, might find a pinned single or two. Our path presented us at length with a bench of rim rock jutting out like a peninsula, a piece of jagged, brushy ground. I edged around the low side of this feature and into position, as Michael picked his way around the top. I lost sight of him completely, and in that big and vacuous space I felt around for some firm ground on which to set my feet.

From my right, two birds got up and out at eye-level, presenting a crossing shot that angled down. Michael’s gun rang out as I watched two birds set their wings, and one I saw distinctly against the darker rock of the draw. I pulled up and took my shot too, one still unfamiliar, aiming down and in instead of up and away. I took my poke and the trailing bird fell into the rocks, neatly folding, the arc of his descent truncated by a rain of lead from the sky. It was a pretty good shot and I was happy with myself for making it. I opened my gun. The dogs, having broken free from whatever point they’d been holding up above me, came tumbling down to help, and I picked my way after them to retrieve my prize.

We looked for that bird for what must have been thirty minutes. It seemed like an eternity. With proximity, the cobbled bottom of the draw turned into a boulder field. There were deep creases and crevices everywhere, thickets of scrub and bands of shadow. I mustered my courage and reached into holes and the dogs made their circles, and we found one or two fine feathers, and nothing more. At some point, dejected, I sat down on a rock. I looked up at the skyline, where again Michael stood silhouetted, the butt of his gun on his hip, barrels to the sky. I could see a little hump of something in his other hand, and knew he’d found his bird.

I sat there and thought for a minute about things disappearing in plain sight, and the empty feeling of lost game, and the way those birds looked falling off the edge, off the toes of my boots. It all seemed, yet again, somewhat disconcerting. I wished for the solidity of my fathers’ calculus, thinking that perhaps somewhere amidst crumbly footing and birds that fell off the earth’s jagged edges, my lack of conviction was to blame. Maybe it had opened up a hole big enough for a bandit bird to slip right through and disappear. Or maybe wild chukars are just built to coax us from our comfortable places, to undo what we are so certain of, to turn our world on its head and leave us breathing hard.

I plunked my way up out of the draw and met Michael. He held a beautiful bird in his hand, and we admired its contrasting colors. Already, far below, there were birds chucking, their calls echoing down the draw. I thought about perspective, and discomfort, and the way we sometimes find what we need, but not what we are looking for.

“Should we see if there are any more along this edge?” asked Michael, tucking the bird in his bag. “There were quite a few more, and they didn’t fly far…”

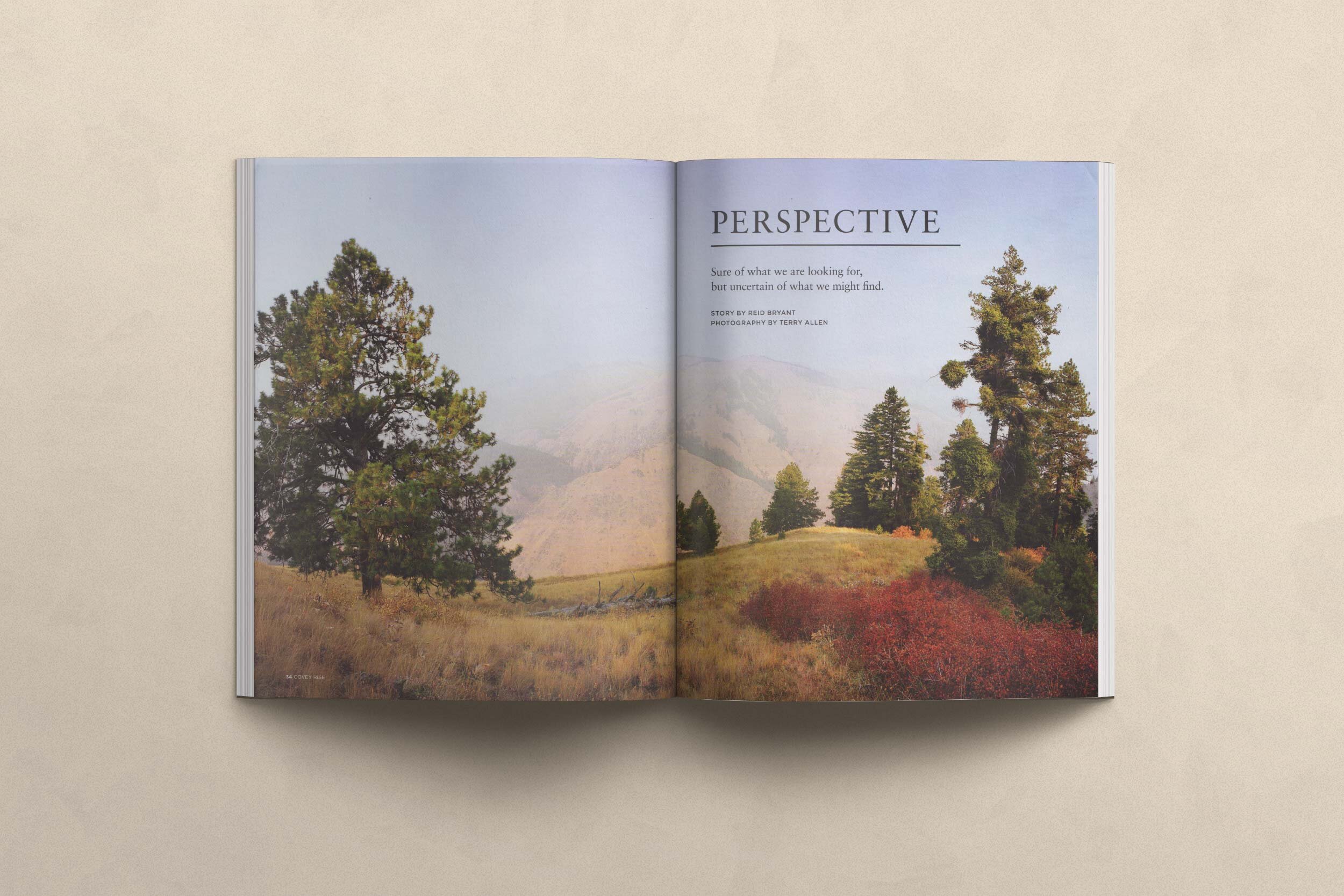

And so we set out on our way once again, quite sure of what we were looking for, but uncertain as to what we might find.