On the Black River

Even as the day was starting, I knew I’d be sick by the end of it. Not bad sick, nothing to warrant real concern, but the kind of sick that would bloom in the coming hours, making me feel as though I’d been shaken too hard, and left out in the cold to founder. Early that morning, on the drive over Eden, I’d felt the first sandy tickle of it in the back of my throat, and I tried to scald it away with a cup of feed-store coffee. That coffee was hot enough to sear my tongue, hot enough, I hoped, to burn off the initial perceptions of illness. It was the first brewed pot of the day, intended for the dairymen of the Black River valley, who held little regard for its quality (or, I imagined, for the frailties of duck hunters). The selling point was, for the farmers at least, comparative cost to serving size. At 25 cents for a 16 oz. cup, not a better deal was to be had in all of northern Vermont.

I might add here that I’m not just some wilting flower. I get sick once a year, almost as a rule, usually with some sort of knock-down, drag-out cold that tenses me up and wrings me out and leaves me a bit peaked for weeks. It usually finds me in January, once the accumulated early mornings and cold-water drenchings and frozen-stump numbings of the past hunting season add up to push me off my pegs. I generally feel I’ve earned it, and don’t fight it too hard. After all, a few days in bed, some Epsom soaks, and a liberal prescription of hot toddies, well, it’s restorative, a necessary replenishing of the soul, and indeed a fair price to pay for all that hard work in the woods.

My wife may, possibly, disagree.

On the day in question, however, I’d swallowed down that raspy tickle and arrived at Dave’s by 5 AM, finding him, as I often did, asleep on the couch. He was wearing his hunting coat and hip boots, for all I knew never having changed out of them after returning from the decoys at Big Hosmer the previous night. I pushed my way through the mud-room without knocking. The kitchen stove was glowing and I wanted nothing more than to huddle over it, embrace it, ward off that creeping chill; but a foul stink stopped me at the door. Dave stirred on the couch, and I grasped at once the source of the odor.The previous night, picking up the fallen among the decoys at Big Hosmer, Dave had found himself a treasure, that is, a treasure in the lexicon of the north country naturalist. Seeking a wayward mallard that had drifted into the weeds, he’d noticed the abandoned and un-hatched egg of a Canada goose, perfectly preserved and flecked with dainty specks of dried mud. He was delighted at the find, as overjoyed as I’d ever seen him (at least since he’d discovered a flying squirrel, quite alive, sealed in an unopened sack of scratch grain). He put the egg in his pocket for safe-keeping, and removed it periodically through the evening for careful, loving inspection. But, at length, he must have let his mind drift to other matters, for, loading the boat onto the roof of the car in the darkness, he’d cracked it with his elbow. The smell was at once overwhelming, and poor Dave was devastated as he pulled his hand from his pocket, his fingers dripping with shell fragments and goose albumen long past overdue.

In any case, Dave had clearly forgotten to change his coat, or, at least, wash out the pocket, likely hoping that he’d be able to scavenge the bits of broken shell for re-assembly. I’m not kidding. This guy built his home out of the remains of a demolished college dormitory…. I asked him once if it was tough to find enough worthwhile material in the cast-off pile of broken clapboards and split ‘two-by’s’.

“Not so much…” he’d responded, shaking his head. “But I’ll tell you, it took a hell of a long time to straighten all those nails!”

Dave stirred some more and I hardened myself against the smell, shut the door and moved closer to the stove.

“You ready?” he asked, coming up from his rest. “They’ll be setting down pretty tight and flying low on a nasty day like today. We could have quite a morning.” The idea of the wet and cold seemed to delight him.

I knew he was right; conditions were, indeed, near perfect. A big system had swung down out of the Canadian Maritimes and the wind was blowing hard from the north, keeping sensible ducks on the water and pushing the reckless off the border lakes and into our laps. But I had no real desire to leave that stove, and I could feel the chill working outwards from my core, pushing back against the dancing warmth of the fire.

“Alright” I said at length. “Let’s get going.”

We had the decoy spread set under the sunken darkness, and the canoe pushed well back in the cattails, but nothing was dropping. We saw some long strings of big ducks, way too high and whistling south, unwilling or unable to swing back to our highballs and circle into the decoys. Dave knocked down a teal, just a single, out of a flock that had been bouncing around the pond all morning. He always referred to them as “silly little teal”, but he and I both favored them. He claimed that they were the finest eating of all fowl, and in general I had to agree, as those I’d been lucky enough to hit had always been fat and full and quick to take on a crispy skin in the oven. Dave claimed that as a kid he and his brothers were sent out to play in the fall afternoons each with a cold roast teal as a treat, and they’d eaten them from their fingers like little brown loaves of bread.

After a while we pulled the decoys and Dave slipped the teal in his pocket, the same pocket, I noted, that had held the goose egg. We paddled back to the car as the sun gained the Lowell ridge, though the light barely changed. In fact, lashing the canoe there in the morning in the Houston cornfield, the wind began to blow harder, and the first drops of rain splattered against my cheeks. I shivered a bit, hoping Dave didn’t notice, and swallowed hard against the sand in my throat.

We drove north and west into the rain on a slick dirt track that bordered the cornfield. Gaining the main road, we passed the Strong Farm mowings, and made our way in turn to the Post Road, where the Black slid gently into sight. We sat there for a moment beside the Post Road Bridge, the car idling as we finished coffee that had gone stale in our mugs. The rain let up a bit, and I halfway hoped Dave would call the whole thing off, but of course, he didn’t. He rolled down the window and began to whistle a little tune, eyeing the sky with deep satisfaction. He sighed.

“What a great day to be a duck hunter.”

And then he was out of the car, jerking the canoe off the roof.

I’d lingered too long in the car, I knew, and the sandy tickle was again on my mind. I shouldered the guns and grabbed the paddles, and slid down the bank into Black River ooze and rain-soaked Canary grass. The sky sunk lower and refused to open up, and I knew I was in for it. Cold rain pooled on my collar, inside my collar, and as the first breach escaped down my back, I knew it’d be a good hard autumn flu, with the fever and chills… the whole shooting match. But in a moment Dave was in the canoe and pushing off, having relinquished the bow seat and the best of the shooting to me… so what was I supposed to do? No duck hunter of any repute would have bailed out at that point.

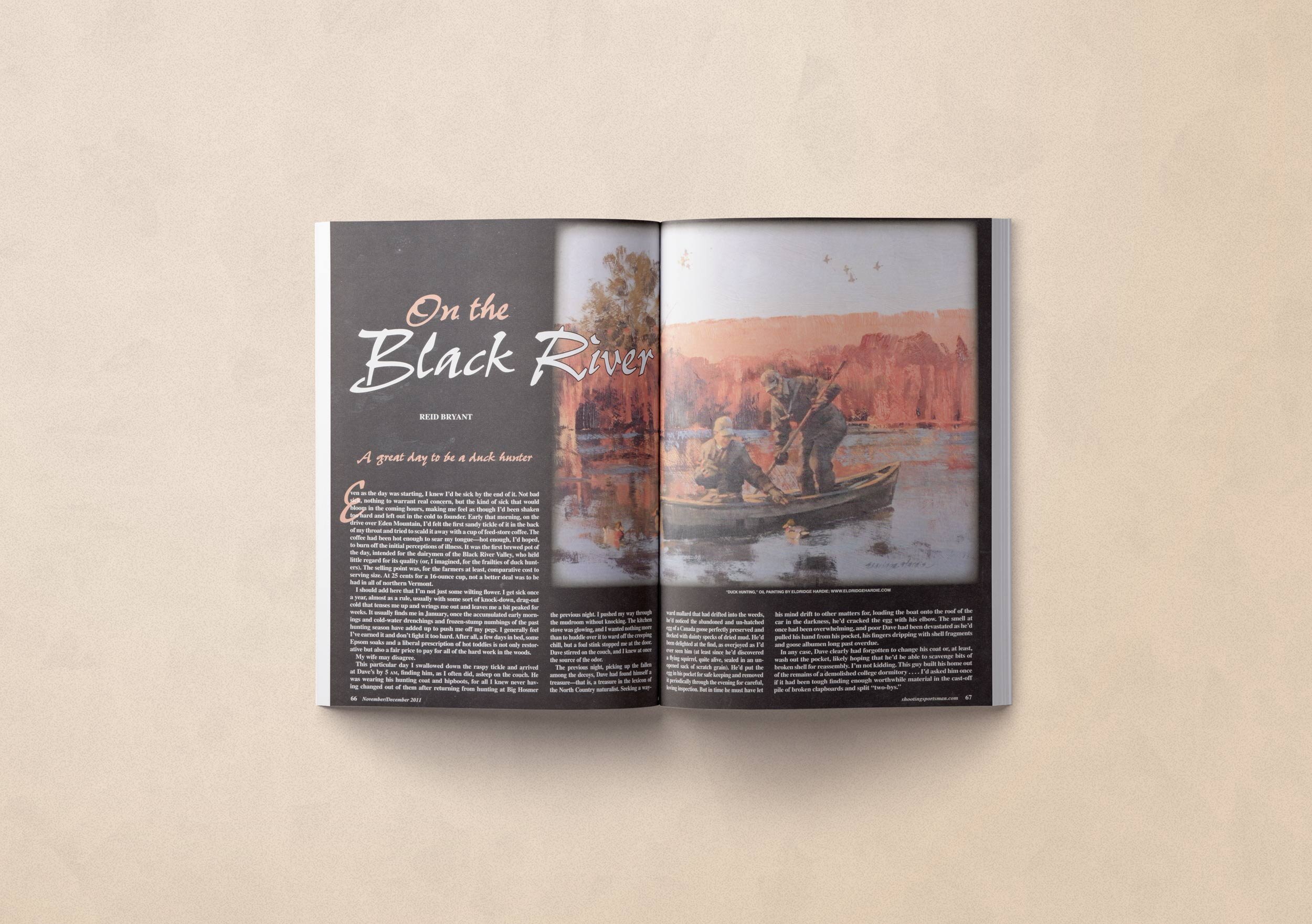

The Black twists north into Canada, framed against a scene at once so beautiful and so hauntingly stark that it confounds even itself. It’s emblematic, I’d maintain, of the north country, a river of slate colored water that underlines a hillside that blossoms come autumn into a cascade of color. The maples of the Black River Valley, the Silver, Red, and Hard Sugar maples simply can’t contain themselves come fall, and I’d like to believe it embarrasses the locals, who are not known for any outward displays. The locals, on the whole, avert their eyes in the bloom of autumn, and are soothed instead by the meandering course of that slate gray water, slipping tirelessly, and without remark, towards the border. The occasional grazed-over riparian is a comfort, and the deep bends of the Black, in the absence of structure, threaten to wash that resplendent hillside clear to Canada. Perhaps the Quebecois, in their unabashed way, might rejoice in the gaudiness of it all.

The Black River has the further distinction of appearing bottomless, as even in the height of summer, its depth is indeterminate. A probe with the canoe paddle tells little; the firmament lies meters deep beneath the ooze of the riverbed. It’s said that old Erving Strong, in the days before skidders, lost a team of woods horses and a load of timber through the ice of the Black one winter, the struggling animals wallowing and disappearing entirely in the muck. Perhaps their ghosts still haunt the marly bottomlands, for the Black remains a spooky and somewhat neglected waterway, even in the bright light of summer. The local kids never swim there.

Under a cold October sky, however, the color of the hillsides was muted and obscure, and the ghosts of the winding river were drenched away in the gathering rain. We hugged the bends and oxbows to the inside, sneaking the nose of the canoe around each corner. My shoulders were tense against the ache of the cold and the wet, and my mind started down that treacherous path of not-caring. I am, at best, a mediocre duck-shooter, and that’s when I desperately want them to fall. Jumping birds in the riverside cattails did not make way for any distraction, and I could feel the pull of self-pity; I was sore, and cold, and wet to the skin, and ready to be done with the float that we’d just embarked on.

And then, just then, the ducks appeared; a magical elixir of sorts, three mallards just downstream, river left. The rain came harder just as I saw them, seeming to pin them down as they jumped. I could almost see, in that moment, their struggle to gain altitude as they departed downriver, and of a sudden, I was no longer cold. The three mallards were framed in flight against that slate colored river and the hulk of mud-bank, and my old Elsie jumped twice, without my hearing it. I saw the belch of fire that followed the shot, and the lone mallard hen winging downstream against her migration, and two lifeless birds on the water.

We overtook the birds on their downstream drift and I became aware of Dave’s narrative. He was re-counting the flush and the shots, and his chin showed a dribble of tobacco juice. He couldn’t believe I’d connected. My own disbelief was not far behind.

“Reid… you have managed somehow to outdo yourself…” he said, and I smiled weakly. The birds, feathers smoothed, in the bottom of the boat, I remembered I was sick. Dave tossed me the pouch of tobacco by way of congratulations, and I shuddered and pocketed it. That was the very last thing I needed.

As we slipped downriver, the rain came in squalls, and all other sound was lost. Dave pulled cross-river at the outside of a memorable bend, and slid up parallel to a shallow slough.

“This is often a good one” he hissed, bending forward and reaching his old pump gun. We let the river carry us down into the mouth of it, where all hell broke loose. A big flock of woodies, nestled up in the blow-downs, jumped together, and Dave and I whanged away. I hit one crossing, and missed a second going with the left barrel. Dave whooped from the stern, and I knew he’d connected, but I also saw that my bird was not yet done in. I bent to reload, and shouted over the rain “We’ve got a cripple!”

“Keep your eye on him” Dave shouted as we slid past, and the bird, a lovely drake, moved awkwardly into the slough. The canoe bucked and the bow dipped, and I turned to see that Dave, in pursuit, had abandoned ship. Now Dave was never one to waste a shell, and hated shooting cripples for fear of damaging meat with an extra shot charge. Nonetheless, he remained ruthless in his disapproval of losing ANY bird, and his commitment to this ethic was fast becoming apparent. Waist deep in the Black River, Dave was moving fast upstream, his hip boots submerged and laden with cold river water. He lurched into the reeds after my swimmer, and disappeared from full view. Through the sheeting rain, I watched the parting reeds, and in that way marked his progress. I saw a canoe paddle rise twice skyward and come down fast in an ax blow, and I heard Dave’s triumphant holler. He emerged, minutes later, with both of our birds, swinging jauntily towards me down the riverbank. With each step, a little geyser of water spurted from his hip boots from within, and I saw that his lips were puckered. I couldn’t hear it for the rain, but Dave was whistling another tune.

“Two woodies” he said, getting back in the boat. “What did I tell you? Not a bad day to be a duck hunter!”

He was right, and sick as I was, I was happy. We continued lazily downstream between the cedars, en route collecting another mallard drake and a big bull black duck that looked to weigh ten pounds. That big drake was a prize worth remembering, and we sat in the rain for a while savoring it. Dave held a wing open and I reached out to touch that glistening swatch of outlined purple, and was surprised by the blunt whiteness of my cold, wrinkled fingers against the feathers. I turned back downriver and Dave shoved off, and around two more bends, the Wylie Hill Bridge heaved into sight.

The Bridge spans a flat and wide section of floodplain pasture, with rolling humps and cattail margins somewhat unfamiliar for the Black River. The place always looks good for a duck or two, and enough of it is safely away from the road that shooting is legal; but for no good reason we never saw ducks there. I cracked my gun and bent my head to finish the float in silent agony. I was hurting and needed to go to bed, and I didn’t relish the long drive home over Eden in wet clothes. I didn’t relish the lack of sympathy on behalf of my mother-in-law, who’d be certain to remind me that it was my own damn-fool fault I was sick. Truth be told, I didn’t relish the idea of plucking and cleaning them, which I’d do in the rain, before collapsing into bed. But I was, I must admit, quite pleased at my shooting, for I’d gotten to within one bird of my limit, a feat somewhat unfamiliar to the average Vermont duck-shooter, and theretofore unknown to me.

I pulled myself back from these murmurings and looked up from the river to note that the rain had tapered to a heavy, hovering mist, and out of the mist, a wing-whistle was sounding. A lone green-wing, whipping out of the cattails, streaked across and towards our bow, departing fast upriver. I snicked the Elsie closed and swung and shot only once, certain, even as I pulled the trigger, that I’d miss. The mount was sloppy, the swing not smooth, and the trigger pull abominable. And by some divine grace, on my behalf anyway, that lone teal fell into the pasture, stone dead.

“Pick up your bird, I’ll meet you at the car” said Dave, pulling the bow towards shore. I trundled over the close-cropped grass to the teal, which lay belly down, wings spread. It too was a drake, and perfect, and it meant my limit. I lifted it gently from the northern Vermont grass. I turned and held that duck warm in one hand, and watched the water, and heard the silence of the finished rain. I turned once more, and trudged down along the riverbank towards Dave, who I could not yet see, but who I could hear, just barely, whistling a happy little tune; I swallowed hard, and couldn’t help but smile.

First published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine Nov/Dec 2011