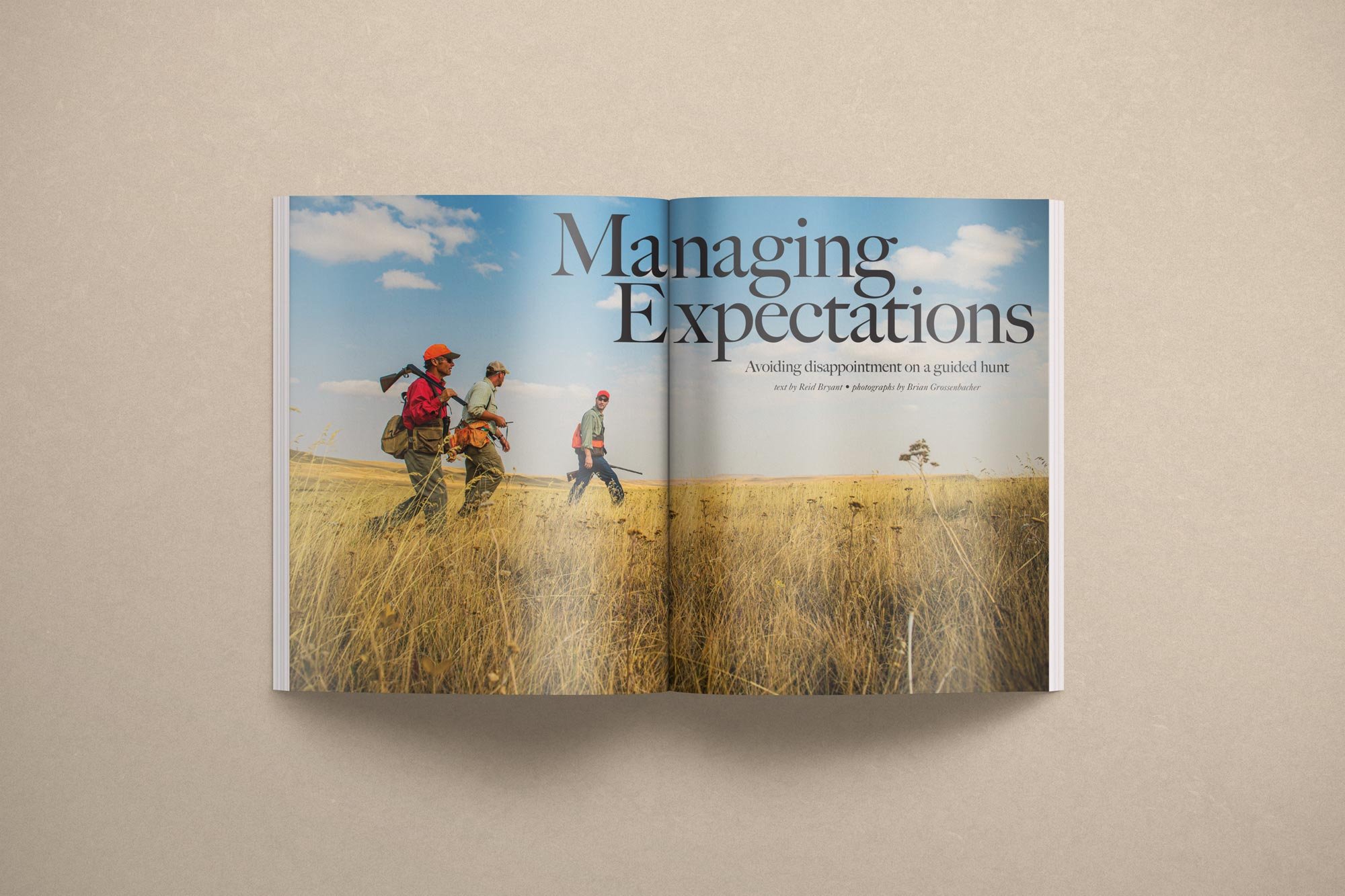

Managing Expectations

A guy I know in Bozeman, Montana, takes a few weeks leave from his government job each fall to outfit hunters north of Fort Peck. He heads to the prairies of eastern Montana in search of big country and long walks, putting half of his clients onto sharptails and Huns through the heat of September, steering the others onto mule deer when November days get short and cold. He is one of those tough-as-nails fellows who takes his time in the outdoors seriously, expecting a similar degree of dedication from his clients. Though he doesn’t gauge his success in gross scores or limits taken, he acquits himself quite well by any measure.

I asked him once which he preferred, guiding birds or big game. His answer was unequivocal: “I would rather guide bird hunters any day of the week.”

I nudged him for an explanation, and he thought it over before responding. “Thing is,” he said, taking the collar off a lanky setter and loading her into the trailer, “I can take a sport out and show him an incredible deer hunt. I can show him a place barren of people for miles around, wildlife and landscape unlike anything he has ever seen. I can put him on a muley half again as big as the biggest deer he has ever considered through a rifle scope, and I can coach him through a shot that drops a magnificent animal clean in his tracks.”

He stopped and considered what he was about to say. “But the thing is, when a big-game hunter walks up on that deer and wraps his hands around its beams, or worse yet asks me what I think it’ll measure . . . well, my heart just sinks. If that deer doesn’t meet or exceed whatever score he has in his head as the benchmark of success, then none of the rest makes an ounce of difference. No matter what I do, no matter what we did together, no matter what we saw or smelled or tasted . . . the hunt will be a disappointment. Way too often it feels like some random yardstick turns what could be a resounding victory into a perceived failure.”

I’ve thought about expectation for some time since my pal shared his story, initially just disparaging a mindset I reserved for big-game trophy hunters. It is true that large mammals lend themselves to an evaluative protocol that can turn their majesty into something academic. But we bird hunters are not immune; we are just as guilty of complicating our days afield with lofty expectations as any breed of sportsman or woman. We, too, can and do place the burden of unmet—and often unspoken—expectations on the guide or outfitter. In a moment of surgical self-assessment, I might even say that bird hunters are just as susceptible to unmet expectations as big-game hunters. We are just a bit more adept at shrouding the realities of our expectations in romantic ideals, quipping “I just love watching the dogs work” or “It’s just a pleasure to be out in God’s country . . . ” right up until the weather goes bad, the birds become scarce or the prospect of a long slog in rough country looms into view.

After several years in the sporting-travel business and after exploring this phenomenon from the perspective of both guide and client, I have some thoughts on the matter of managing expectations. I begin with the underlying premise that it is absolutely OK to have expectations of a hunt, but in order to avoid disappointment those expectations must be owned, admitted to and honestly evaluated. Not only is it on each of us to seek out those experiences that have a legitimate chance of meeting our wants, but it also cannot become the burden of the guide or outfitter to interpret—let alone meet—expectations that we do not give voice to. I’d pose that in having expectations of a hunt, we must take correlative responsibility for the realization of them.

With this philosophy in mind, what follows is an exercise: a series of questions that can help hunters explore the realities of their expectations and communicate those criteria to a would-be guide, outfitter or lodge. It goes without saying that specifying expectations up front in clear, honest terms to ourselves as well as our intended hosts is the first step in ensuring that those expectations are met. Communication of clear expectations also helps would-be clients assess prospective outfitters, guides and destinations. This process of assessment, evaluation and communication requires some discipline, but the effort is very much worthwhile.

Intended Quarry and the Demands of Pursuit

There is something undeniably romantic about hunting wild birds in wild country and something equally admirable about folks who do so. The stakes of the game are high, pitting the hunter against worthy adversaries of quarry, landscape and the whims of Mother Nature. That said, hunters who commit to wild birds must be willing to cope with disappointment. They need to understand that wild birds persist for a very good reason—namely that they are given to places where predators are hesitant to pursue them. They are tough to find, tough to kill and inherently rare. Dedicated wild-bird hunters, even those in the company of seasoned guides, must acknowledge some real and significant obstacles. Therefore, when seeking a guide, outfitter or lodge, it is vital to consider the following:

· Do you want to hunt wild birds exclusively, or do you simply like the idea of hunting wild birds exclusively? Are you willing to come up empty for a day or two and remain vulnerable to poor hatch years, challenging weather/climatic conditions and birds that are simply few and challenging? It is fine to let the aspirational identity associated with wild-bird hunting rub up against the challenges and discomforts of its reality. A little discomfort may be worth the identity gained, but then again, it may just take the fun out of the experience.

· What level of physical exertion is comfortable for you? Are you willing to put in very long days in steep, prickly, hot, uneven terrain that requires a level of fitness? Does a five-day trip really make sense if after Day 2 you are likely to be whipped both physically and emotionally?

· Have you put in—or are you willing to put in—the training time? Are you willing to run, walk and/or work out with weights? Are you a smoker or overweight? Can you shoot? More importantly, can you shoot at unpredictable targets in uneven terrain while breathing hard from a long uphill slog?

It is only natural that there be something of a gulf between how we’d like to see ourselves and who/how we really are. In booking a hunt it is important to be as honest with yourself as possible, especially regarding physical limitations and dependance on measurable successes like shots fired, coveys flushed or birds bagged. Also recognize that there is nothing wrong with wanting shorter, easier walks, a bit more reliable shooting and maybe a cigar to enjoy along the way. All these elements can be made possible but likely not on the same hunt. An honest take will ensure that the trip lives up to honest expectations.

The Value Proposition

Let’s face it: In this day and age, many hunting excursions, especially those that are guided and/or outfitted, come with a not-insignificant price tag. To my mind, that price tag can be justified by looking honestly at the cost of human hours, guide vehicles, dog food, land leases, insurance and lodge buildings or facilities. That said, different providers allocate money toward different interests. Some destinations put a premium on the lodging, food and beverage experience, offering world-class dining and top-shelf alcohol in a facility fit for royalty. Those amenities come at a cost. Other destinations maintain lodging and dining amenities at a spare but adequate level and instead allocate the bulk of the capital to ample land access or bird propagation. It is important, therefore, to be clear about the amenities and resources on which you care to spend your money. Consider the following:

• A destination may have exceptional food and top-shelf liquor built into the price of the trip. Are you a light or non-drinker? Are you just as happy with a burger as you are with a Wagyu tomahawk? Would you be satisfied putting in a long day in epic country and crashing in a rustic cabin, or would you prefer a steam shower and Egyptian-cotton sheets. Again, either is fine, but all cost money. Consideration of where that money is allocated may determine which destination or operator best suits your needs.

• Make sure to ask up front about additional prices that you may have failed to factor in, like bird overages, service fees and gratuities, and so on. Does bird processing cost extra? Is ammunition included in the trip price? Does the shotgun you choose to borrow have a rental fee associated with it? Again, the cost of doing business in the hunt space is significant, and guides, outfitters and lodges can’t be expected to swallow all those costs. If you are hunting on a budget, an extra 10 percent on top of the anticipated tab can be a bitter pill to swallow. Moreover, you should always factor in a bit of cash for a deserving guide or exceptional staff. Ask your host about inclusions and exclusions up front and be extraordinarily explicit with your questions. Nothing cultivates resentment quicker than the creeping feeling that you aren’t getting what you paid for or, conversely, that you are being nickeled-and-dimed or taken advantage of.

Logistics

Logistics are a significant source of angst for clients who have an image in their heads of how the hunting day should go and are presented with something far different. It is vital, therefore, that no assumptions are made. An outfitter cannot be expected to magically assess personal preferences for the flow of pace and schedule. To manage expectations, you might first ask yourself how you like to hunt and why. Don’t judge the answers, but note them. Remember: A hunting trip or guided day should meet your expectations of fun and recreation. They should not require of you participation in an experience that is undesirable, overly uncomfortable or generally lacking in fun. Consider the following:

· Do you want to avoid long travel times to hunting areas? Is “windshield time” with a guide enjoyable to you, or is it an awkward burden? Is it required that you follow guides in your own vehicle to hunting areas, or do they provide the transportation? A two-hour drive through beautiful country is a joy for some and an excruciating waste of time for others. Ask up front, and note your response to the answer.

• Do you want to hunt in a mixed group with people you don’t know? This is often a consideration for single hunters who may be lumped together with an existing group in the interests of an outfitter’s cost-effectiveness. That said, it can be uncomfortable to hunt with a stranger or group of them whose safety, pace, aggressiveness and demeanor may not match your own. Often a single hunter who wishes for a single guide incurs an upcharge, which may or may not be worth the cost. Regardless, ask the question, and be clear on your preference. Being the odd person lumped in with a group can prove a lonesome experience or can avail you to a host of new friends. It all comes down to your willingness to be that odd person and your approach to the experience.

• Recognize, too, that you should ask a lodge or outfitter about the hunter-to-guide ratio. Consider the example of four hunters on a quail wagon when only two are allowed on the ground at a time. If you would rather walk in on every point, that’s fine, but make sure to clarify that this is what you will experience on the hunt.

• Do you want to hunt your own dog and kennel him at the destination? This is an important question and one that requires honest self-assessment. We all have a tendency to believe that our dogs are the best that have ever flushed or pointed, but it goes without saying that dogs on a guide string or in a lodge kennel likely have handled more birds than any personal dog could hope to. Is the goal, therefore, to shoot birds over seasoned dogs or to get contacts for your dog? If you are hunting with a friend, be sure to understand that he or she may not share your enthusiasm for your dog’s performance. Moreover, if you and a friend are splitting the guide fee, the use of a second-string dog may chafe even the most long-suffering companion. A guide who is asked to watch you work your dog must still receive the full guide fee and can’t be held accountable for any blunders that you or your dog commit.

• If you do take your dog on a hunting trip, don’t assume that he or she will be allowed to sleep in your room. Lodges have their own pet guidelines for a variety of reasons, and dog protocols should be addressed before you arrive.

Success By the Numbers

Numbers are a tidy means of measuring success or failure. Numbers can also be the seeds of disappointment. The number of birds shot is not necessarily indicative of the guide’s ability, the health of the resource or even the prevalence of birds in the cover. Birds brought to bag represent the intersection of shooting efficacy, the ability of a hunter to get to a point or flush quickly and efficiently, the quality of dogwork, the tenacity of guides and the willingness to put in the miles and time. The bottom line is that a full bag is the result of a team effort and a dose of luck; a light or empty bag is rarely attributable to any single factor. Therefore, consider assessing the success of a day by asking the following questions:

· Did you get some shooting in, even if few birds were bagged?

· Did the dogs bump birds out of range or otherwise mishandle them? If so, did the guide make changes to ensure better dogwork?

· If birds were few, did the cover seem viable? Was there sign that birds had been in the area or had been using the resource?

· Were you able to cover the required ground to up the likelihood of encountering birds, and were you in position to make good on viable, ethical shots?

· Did you “move” a lot of birds but not have many shooting opportunities because the cover/foliage was thick, as often is the case with early-season grouse and woodcock. Did you miss out on shooting opportunities because the birds were spooky and got up out of range, as is typical with late-season prairie grouse and pheasants?

These are hard questions to ask oneself, especially when bush-whipped and empty-bagged. At the end of a long, birdless, expensive day it is tempting to lay some blame. It is imperative, however, to be honest about shortcomings, be they your own or those of the guides and/or dogs. Remember: No hunter, guide or dog wants to come home skunked. It is vital to assume that you and your team are doing your collective best to find and kill a few birds even on the days when the stars just don’t align.

Conclusion

I agree with my guide pal that bird hunters are a refined, considerate and capable lot. But they—we, I should say—are not without imperfections. Like our big-game-hunting brethren, we carry into the field our own brand of expectation, which, unmet, can sully what should be a beautiful pursuit. The remedy to potential disappointment is an honest assessment of our wants and expectations, ownership of them and a willingness to plan our hunts in a manner that attends to our true preferences. Bird hunting, after all, should be fun. It is up to us as individuals to determine what fun looks and feels like and to recognize that it can at times elude us. That should not—I daresay cannot—mean that the time spent pursuing birds and the joy they bring are not altogether worthwhile.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine