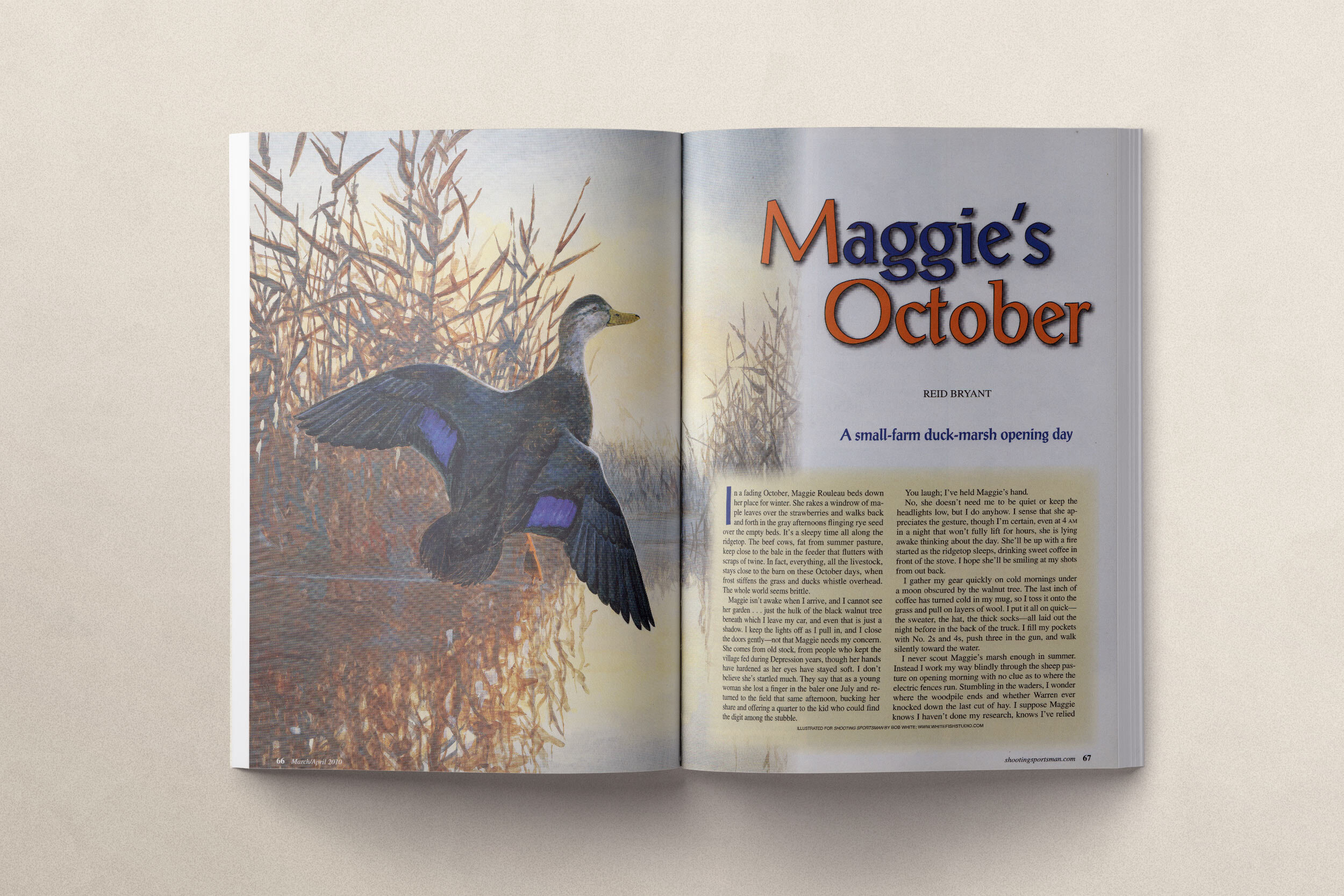

Maggie’s October

In a fading October, Maggie Rouleau beds her place down for winter. She rakes a windrow of maple leaves over the strawberries, and walks back and forth in the gray afternoons, flinging rye seed over the empty beds. It’s a sleepy time all along the ridge top. The beef cows, fat from summer pasture, keep close to the bale in the feeder, which flutters with scraps of twine. In fact, everything, all the livestock, stays close to the barn on these October days, when frost stiffens the grass and ducks whistle overhead. The whole world seems brittle.

Maggie isn’t awake when I arrive, and I cannot see her garden… just the hulk of the black walnut tree beneath which I leave my car, and even that is just a shadow. I keep the lights off as I pull in, and I close the doors gently; not that Maggie needs my concern. She comes from the old stock, the people who kept the village fed during Depression years, though her hands have hardened as her eyes have stayed soft. I don’t believe she’s startled much. They say that as a young woman she lost a finger in the baler one July, and returned to the field that same afternoon, bucking her share and offering a quarter to the kid who could find the digit among the stubble.

You laugh… I’ve held Maggie’s hands.

No she doesn’t need me to be quiet, or keep the headlights low, but I do anyhow. I sense that she appreciates the gesture, though I’m certain, even at four, in a night that won’t fully lift for hours, she is lying awake thinking about the day. She’ll be up with a fire started as the ridgetop sleeps, drinking sweet coffee in front of the stove. I hope she’ll be smiling at my shots from out back.

I gather my gear quickly on cold mornings, under a moon obscured by the walnut tree. The last inch of coffee has turned cold in my mug, so I toss it onto the grass, and pull on layers of wool. I put it all on quick, the sweater, hat, and thick socks, all laid out the night before in the back of the truck. I fill my pockets with #2’s and #4’s, poke three in the gun, and walk silently towards the water.

I never scout Maggie’s marsh enough in summer. Instead, I work my way blindly through the sheep pasture on opening morning with no clue as to where the electric fences run. Stumbling in the waders, I wonder where the woodpile ends, and whether Warren ever knocked down the last cut of hay. I suppose Maggie knows I haven’t done my research, knows I’ve relied solely on her reports of ducks flying and gabbling in the potholes. I imagine she knows how I’m cursing myself now, in the dark of opening morning, and I’d guess this lack of foresight chafes her Yankee pragmatism. But Maggie is generous with her tacit clemency, and as I make my way into the bank-side brush I see she’s done my scouting for me. There, against the black of the channel, Maggie has built a crude blind of cut cattails and brush. I take my seat on the sap bucket and thank Providence for her decency, and another opening morning.

Maggie’s marsh is tiny and perfectly hidden, just beyond the rise of the sheep pasture. If you knew to look, you could almost see it from the road. It’s just the thing for one hunter, or maybe for two who trust each other’s restraint. I almost always hunt it alone. It’s the flooded remains of a natural swale, which rose to standing water when Maggie and Bob had already lived in the house through half-grown children, he saving his checks from United Twist Drill to establish a trout pond out back. The pond surfaced seemingly out of the switch-grass, rising behind the dam that Bob and Maggie laid in. The swell pushed the pheasants from among the hummocks, and the ducks settled in almost at once, happy to hole up in the floodwater maze, and feed on seedheads. The water remained too shallow and warm for trout to take hold. Undaunted, Bob enjoyed the horn-pout that proliferated wildly, and Maggie’s skillet popped and crackled under many a morning’s catch.

In the dark of my opening morning, all this history swirls somewhere in the back of my mind, as I look out across the darkness. It is Bob, gone these few years, who visits me now. On the first mornings of my hunting here, it was he who answered the phone to assuage the concerns of the neighborhood crime watch, who’d woken to the clatter of my misguided shots.

“It’s just the new kid from the farm up the way” he’d said. “He’s a duck hunter and it’s my land… and besides, maybe this’ll get you all out of bed on time! This new kid can shoot all the ducks he wants out of my pond.”

When I’d stumble back out of the muck, late for work myself, he and Maggie would squeeze together there at the window, a cup of Maxwell House waiting for me, and they’d always be properly impressed with my Black Duck or Mallard, and properly empathetic when my head hung under the weight of the horse collar. They admired the beautiful Wood Duck drake whose feathers I smoothed for a flying mount, much in the way they admired my first-born daughter: looking long enough to really see what was held before them.

So in Maggie’s blind I sit and wait, realizing finally that I’ve arrived, once again, hours earlier than necessary. A beaver slides from the brush and tracks methodically back and forth along the weeds, and the dark and the cold hang heavy on my shoulders. I try not to shiver, wiggle my toes. Staring up at the stars, I try to pray a little, nothing formal, just offerings and thanks. I close my eyes and I open them at intervals, losing myself in something like sleep that carries me closer, minutely closer, to shooting light. A big duck quacks out there in the potholes, somewhere west and slightly south. A woodie whistles, or maybe I made that one up, again too eager. The beaver slaps his tail and breaks the unreflecting mirror of water and I’m fully awake. Shooting light is just minutes now. I wait, and shiver a little bit more.

Sometimes ducks come in so fast you’d think a falling star was landing in your lap. A big Black drake screams out of the sky from the east so hard and fast I don’t know how he’d ever even seen the decoys. The sound of his wings is like a freight train whistle screaming, and he hits the water hard and paddles off the north end of the channel and into the lily pads. I try to slow my heart. I blow a soft quack on my call, wait, and give another little grunt. I dare not try a feed call, certain that it will only embarrass the big fellow and drive him off. He turns, and heads back into the dekes, just a black dark profile, edging closer then turning away just as I tense to rise and shoot. It’s a sickening thing to have him turning back and forth out there, just out of certainty. I start to think about that duck, what’s spinning there in his tiny mind, what he’d seen as he swept in over my head this morning. Has he seen today’s sun yet, felt it on his back as he rides its first light just over the horizon and into lily-strewn water? I remind myself that these thoughts make me a mediocre hunter, just as the duck decides to come in close. He paddles right in front and I rise just as he does, alert seemingly to my indecision. He lifts and hovers in his departure, and I hit him hard, once on his rise, and again on his tumbling fall. Somewhere, deeper in, a couple of woodies burst out, and I hear them squall. But I’ve learned to keep my eye on the downed Black, and to not be greedy. Third shots seem always to get me in trouble.

The drake is flapping and turning a broad circle in water that can’t be a foot deep. His head’s flopping awkwardly side to side, but he keeps turning, and I put another charge into him to stop his moving. As the silence descends, I want the big duck in my hands. I walk south along the brush to where Bob’s old johnboat is up on sawhorses. I roll it off and drag it into the water, pushing off with the paddle that was tucked inside. I take two strokes out over the channel, over the deeps and the sucking marl, and into the pads of the weedbed where he went down. All around me there is emptiness: a big sky caught between night and day, and only a hint of a glow in the east… a thin clear cold that shimmers beneath the wind, and weeds and water below that.

I make the circles, and I find the wad and bloody feathers, but I don’t find a duck. I thrash among the hummocks, slapping the grass and cattails with my paddle, and I trudge through chest deep ooze in widening rings. I sink my hands to the elbows in muck thick as oatmeal and can’t imagine a duck being able to dive in the stuff. Finally I sit in the johnboat under a full-risen sun, and am sick about the whole damn thing.

Maggie is at her window with a cup of coffee in her cracked hands, and I see soil dark under her fingernails. She hands me the mug, and I know she sees my disappointment.

“Any luck?” she asks cautiously.

I tell her.

“Well, they’re tricky” she reminds me, and tells me the story we’ve all heard. You know the one… the crippled duck that feels itself dying, and dives beneath the surface of some October waterway, to cling in death to a clump of submerged debris.

I don’t feel any better, though I thank her for the coffee, and I don’t change out of my wet waders for the drive to work. I’m not yet ready to let go of a lost duck on opening morning.

At noon I return, and again in the afternoon, paddling the johnboat in another maddening series of concentric rings. No black duck, and I don’t shoot at the green-heads that jump. Maggie’s in the kitchen canning pickles, and she waves but we don’t speak.

In the early evening I drive home, down the dirt driveway to the little house where my family waits. My wife meets me at the door, and points to the woodshed.

“Maggie brought you something” she says with a gentle smile, sensitive, I imagine, to my disgust at losing the year’s first duck.

At the very top of the woodpile, on the ash splits that we’ll burn tonight, lies the big black drake, its feathers smooth and cold and wet. It’s not even bloody, and its eye is open, black and papery opaque and unseeing. There is a bowl of fresh cranberries and a note:

“Found this old boy in the outlet. Best roast him till crispy with lots of salt and butter, and make sure your wife makes some sauce from these berries. That’s how Bob used to like them anyways. Hope to see you tomorrow morning. - Maggie”

First Published in Shooting Sportsman.