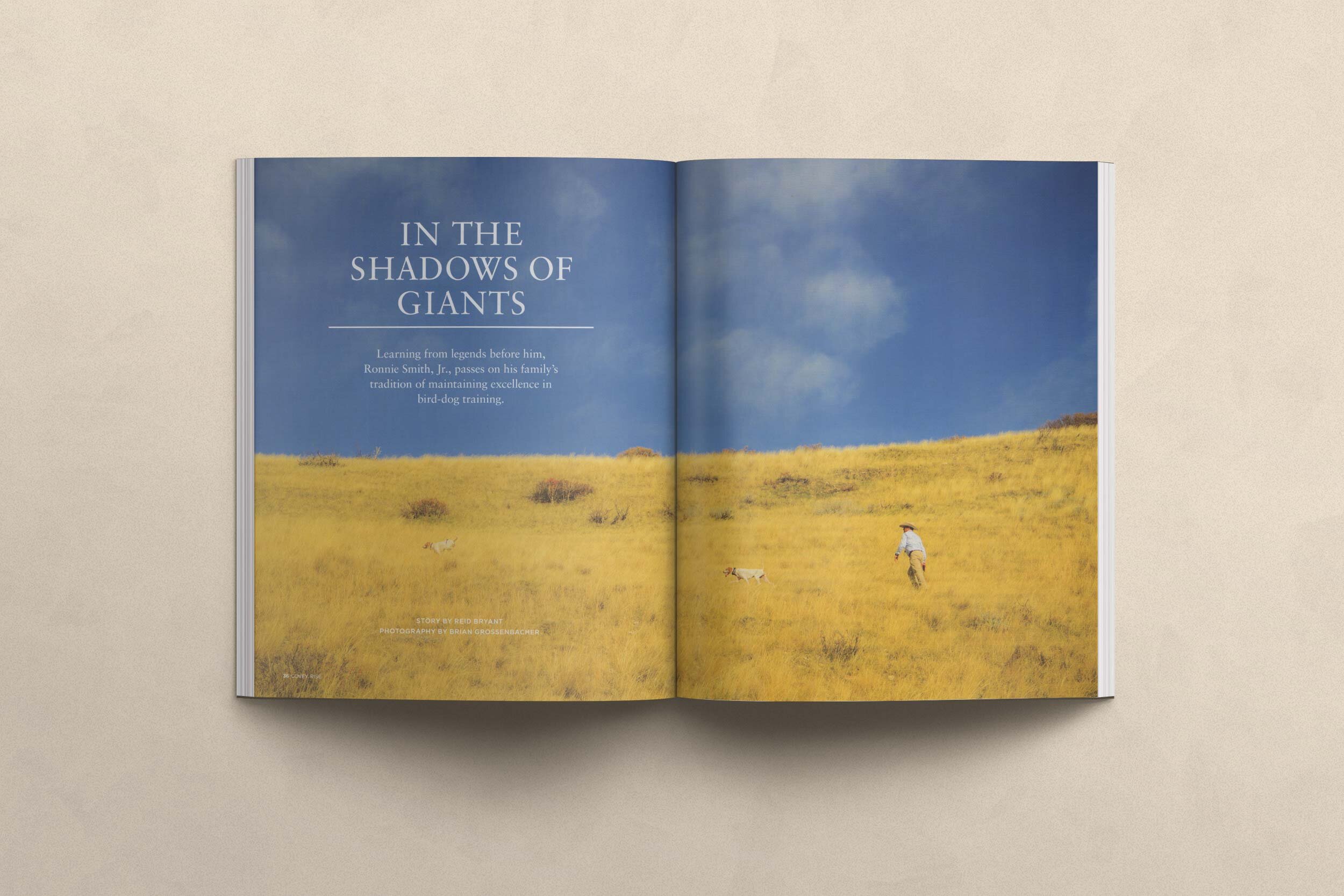

In the Shadows of Giants

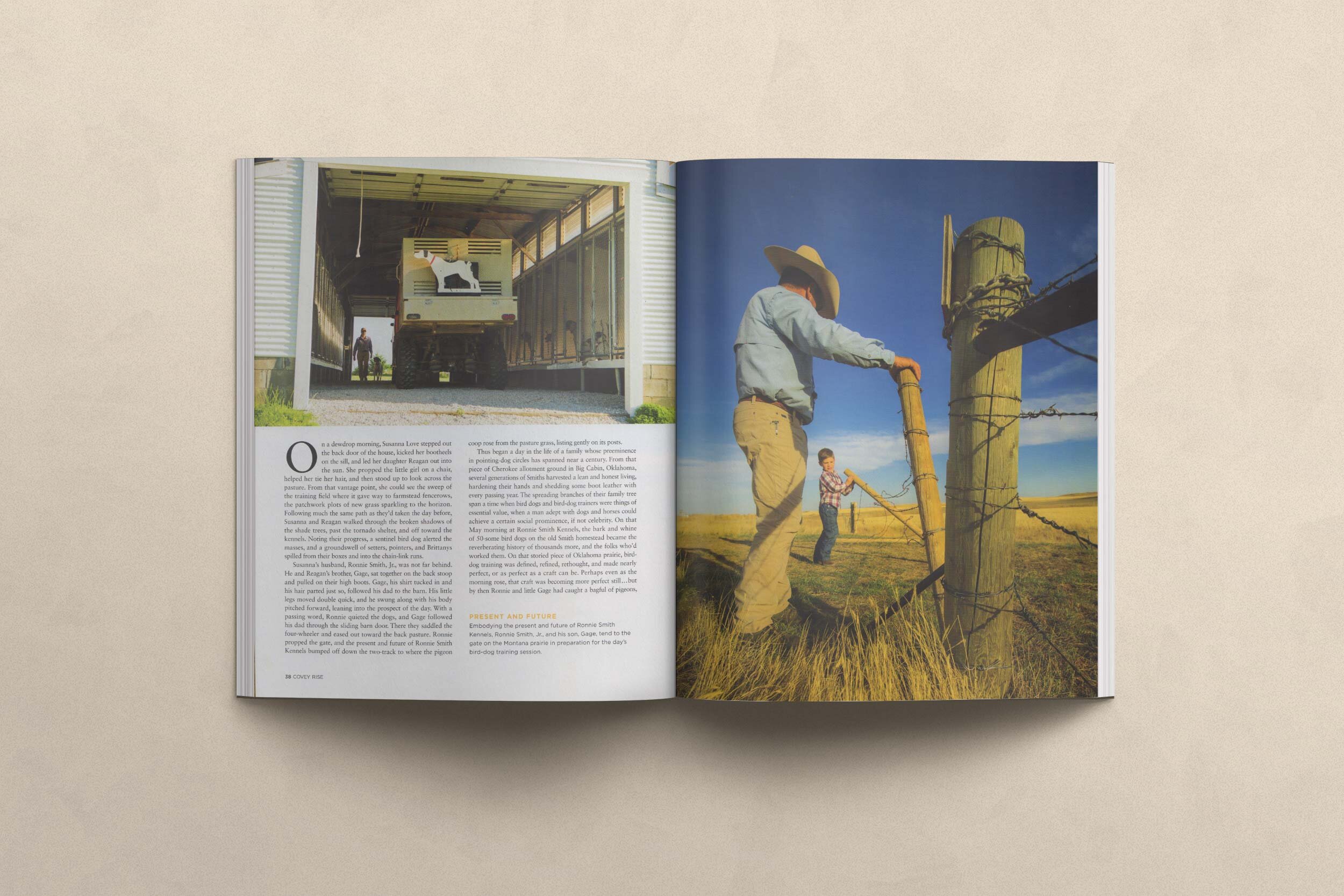

On a dewdrop morning Ronnie Smith Jr. and his little boy Gage pulled on their high boots and lit out across the dooryard past the kennels. Noting their progress, a sentinel bird dog alerted the masses, and a groundswell of setters and pointers and Brittanys spilled from their boxes and into the chain link runs. Gage, his shirt tucked in and his belt buckle centered and his hair parted just so, kept pace with his dad. His little legs moved double quick and he swung along with his body pitched slightly forward, as if leaning into the work of the day. With a passing word Ronnie quieted the dogs, and Gage followed his dad through the shadows of the sliding barn door. There they saddled the four-wheeler and eased on out towards the back pasture. Ronnie propped the gate, and the present and future of Ronnie Smith Kennels bumped off down the two-track to where the pigeon coop rose from the pasture grass, listing gently on its posts.

As the noise of the four-wheeler subsided, Ronnie’s wife Susanna Love opened the back door of the house, kicked her own bootheels on the sill, and led Gage’s twin sister Reagan onto the back patio. She propped Reagan on a deck chair and helped the little girl smooth her hair, and then stood up to look across the pasture, her hand shielding her eyes. From that vantage she could see Ronnie and Gage already at work, Ronnie waving a net through the commotion of pigeon wings in the coop and pushing birds into the bag that Gage held open. Following much the same path as the boys had taken, Susanna and Reagan walked through the broken shadows of the shade trees, past the tornado shelter, and off towards the kennels. There were nursing dams to feed in the whelping pens after all, and dogs to lead to the stake-out chain, and a tireless parade of kennels and water buckets to spray clean.

Thus began a day in the life of a family whose pre-eminence in pointing dog circles has spanned near a century.

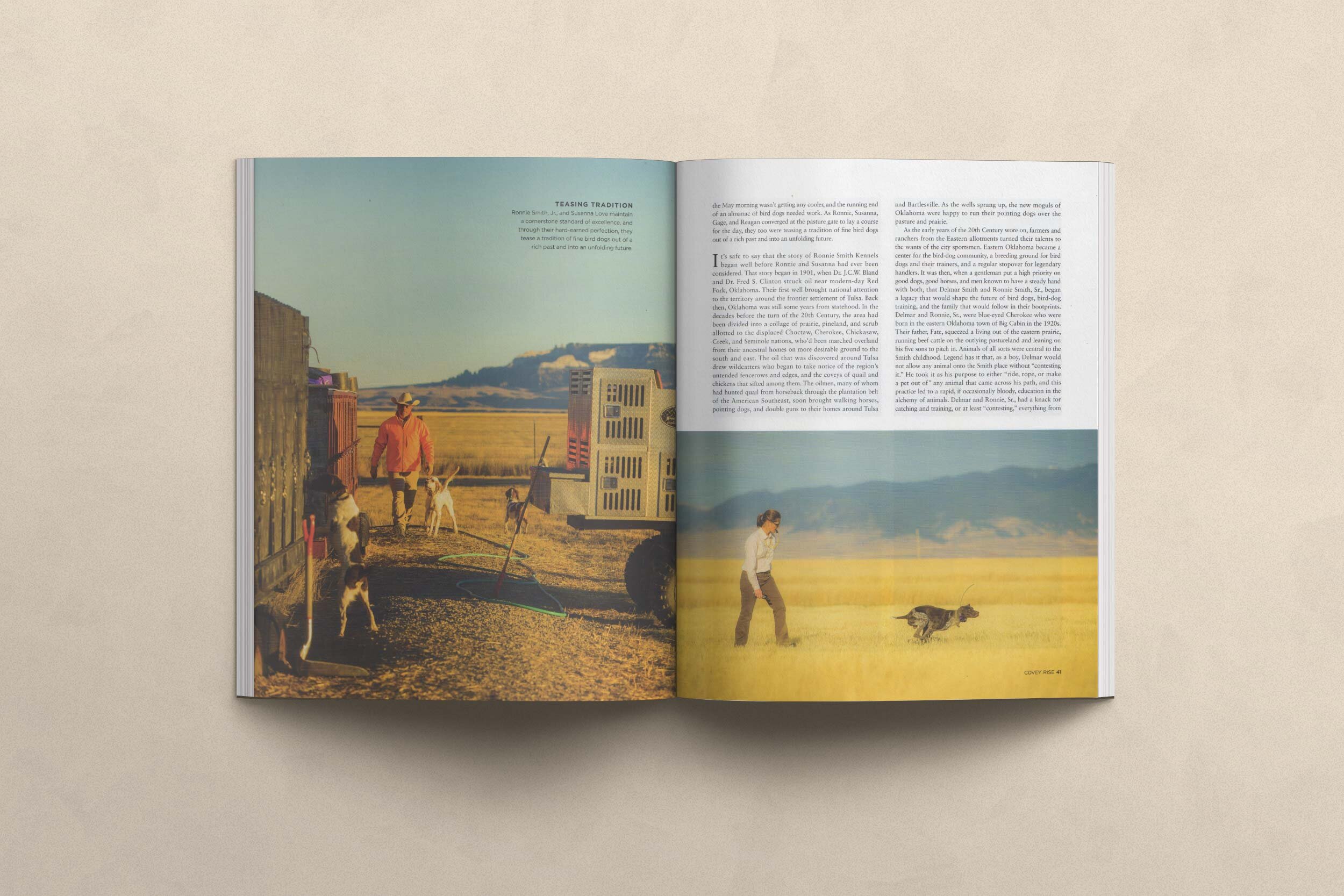

From that piece of Cherokee allotment ground in Big Cabin, Oklahoma several generations of Smiths have harvested a lean and honest living, hardening their hands and shedding a little boot leather with every passing year. Among the roots of the Smith family tree there are ranchers and horses and livestock, lariats and lead ropes and check cords, and a central reliance on workdays shared with working animals. The spreading branches of that family tree span a time when bird dogs and bird dog trainers were things of essential value, when a man adept with dogs and horses could achieve a social prominence, if not celebrity. Sitting there at Ronnie Smith Kennels on the old Smith homestead I listened to the bark and whine of fifty-some bird dogs, and the reverberating memory of thousands more; on that very piece of Oklahoma prairie, bird-dog training was defined, refined, re-thought, and made near perfect, or as perfect as a craft can be. Perhaps even as I watched it was getting more perfect still… but by then Ronnie and little Gage had caught a bagful of birds, and the May morning wasn’t getting any cooler, and the running end of an almanac of bird dogs needed work. As Ronnie and Susanna and Gage and Reagan converged at the pasture gate to lay a course for the day, they too were teasing a tradition of fine bird dogs out of a rich past and into an unfolding future.

*

It’s safe to say that the story of Ronnie Smith Kennels began well before Ronnie Smith Jr. and Susanna Love had ever been considered. That story began in 1901, when Drs. J.C.W. Bland and Fred S. Clinton struck oil on a property of Creek Indian allotment near modern-day Red Fork, Oklahoma. Their first well brought national attention to the territory around the frontier settlement of Tulsa. Back then, Oklahoma was still some years from statehood; in the decades before the turn of the century the area had been divided into a patchwork piece of prairie and pineland and dust seen as lacking in prospects by the US government. The land had been allotted to the displaced members of the Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations, who’d been marched overland from their homes on the more desirable ground to the south and east. But the oil that was discovered around Tulsa changed perceptions immediately, and perhaps irrevocably. Oil drew the interest of wildcatters, and in short order a stream of both money and eastern business cut a channel into what would become Oklahoma. As that wealth settled into the area and re-doubled itself, those newly-minted oil moguls began to take notice of the region’s subtler abundance, namely the plump little birds that coveyed and called in the broken and blackberry-tangled corners.

Through the early 1900’s, prairie grassland and untended fencerows provided feed and cover, and in boom years Oklahoma’s native bobwhites and chickens were thick. Birds that had provided the locals little more than an apt alternative to beefsteak drew a good deal of interest from the eastern oilmen, who had hunted quail from horseback through the plantation belt of the American southeast. In short order walking horses and pointing dogs joined the oilmen in their homes around Tulsa and Bartlesville, and as the wells sprung up the new residents of Oklahoma were happy to run their pointing dogs out over the pasture and prairie.

As the early years of the 20th century wore on, farmers and ranchers from the eastern allotments turned their talents to the wants of the city sportsmen. Many Okie ranchers applied the knowledge they’d gained working cutting horses, roping horses, and ranch dogs to the increasingly profitable, and socially enviable, work of bird-dog and walking-horse training. Those gifted with a steady hand came to be in demand as a new and honorable career surfaced and gained a degree of cultural prominence. All of this came about during a time when America afforded the crafts of horse training, dog training, and bird dog trialing a great deal of respect. Agrarian know-how and a rural astuteness had gained a newfound artistry as wealthy folk around Tulsa became more eager to have the best of the best horses and dogs when hunting or trialing season came to pass. Eastern Oklahoma became a center for the bird dog community, a breeding ground for bird dogs and their trainers, and a regular stopover for a who’s-who of legendary handlers. It was then, in that era when a gentleman still put a high priority on good dogs, good horses, and men known to have a steady hand with both, that Delmar Smith and Ronnie Smith Sr. began a legacy that would shape the future of bird dogs, bird dog training, and the family that would follow in their boot prints.

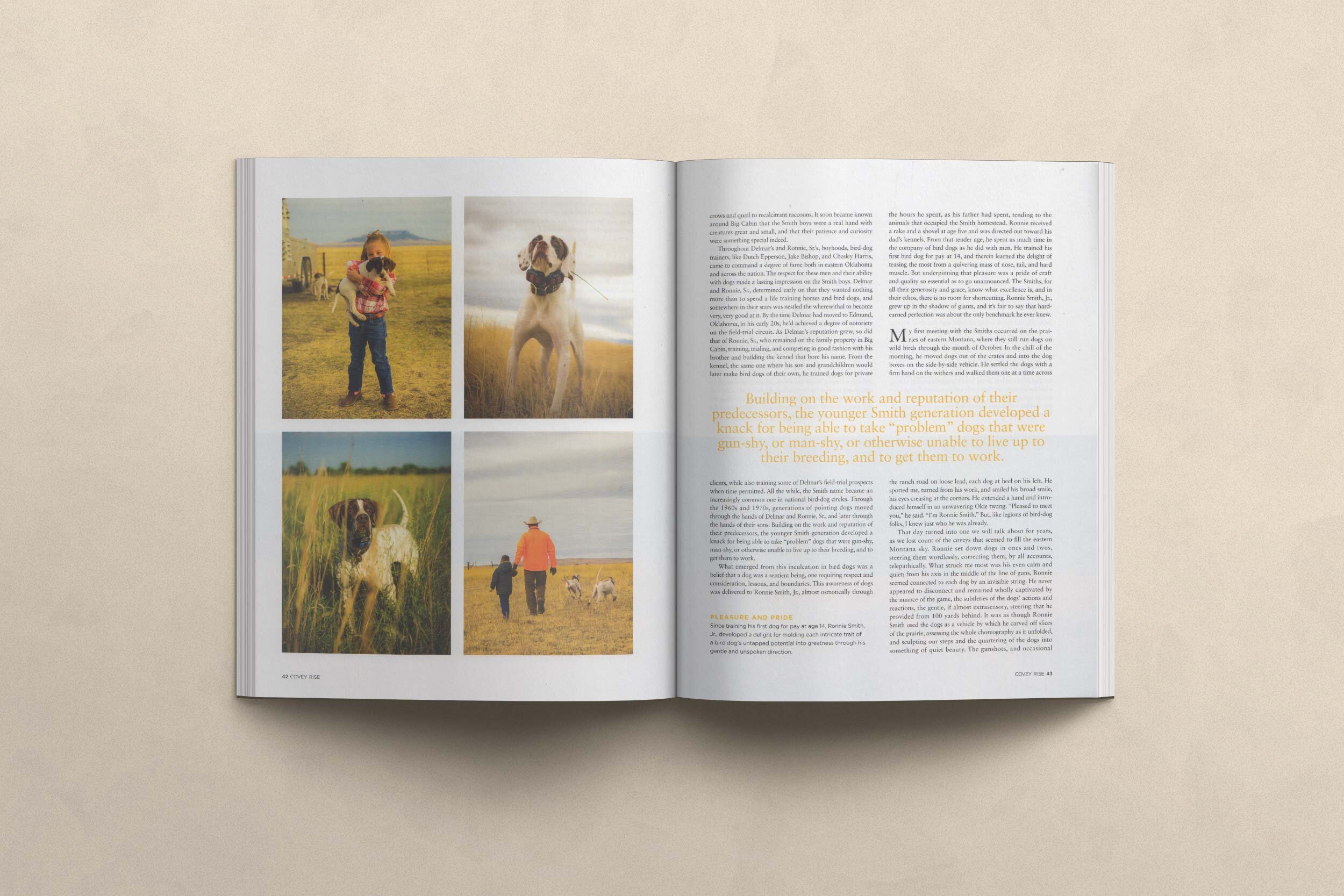

Delmar and Ronnie Sr. were blue-eyed Cherokee who were born in the eastern Oklahoma town of Big Cabin in the 1920’s. Their father, Fate, squeezed a living out of the eastern prairie, running beef cattle on the outlying pastureland and leaning on his five sons to rise before dawn each morning, to saddle their horses, and to feed and check the cattle. Animals of all sorts were central to the Smith childhood; legend has it that as a boy Delmar in particular would not allow any animal onto the Smith place without “contesting it”. He took it as his purpose to either “ride, rope, or make a pet out of” any animal that came across his path, and this practice led to a rapid, if occasionally bloody, education in the alchemy of animal behavior. Delmar and Ronnie (Sr.), had a knack for catching and training, or at least “contesting”, everything from crows and quail to recalcitrant raccoons; more than once the boys chased down a coyote on horseback and roped it like they did the family’s steers. As children, and even more so as adults, Delmar and Ronnie Sr. spent long hours just watching animals, studying their responses to environment and contact and stress. It soon became known around Big Cabin that the Smith boys were a real hand with creatures great and small, and that their patience and curiosity was something special indeed.

Throughout Delmar and Ronnie Sr.’s boyhood men like Dutch Epperson, Jake Bishop, and Chesley Harris came to command a degree of fame if not fortune both in eastern Oklahoma and nationally. The respect for these men and their ability with dogs made a lasting impression on the Smith boys. Ronnie Sr. and Delmar determined early on that they wanted nothing more than to spend a life training horses and bird dogs, and somewhere in their stars was nestled the wherewithal to become very, very good at it.

By the time Delmar was in his early twenties he’d moved to Edmund, Oklahoma, to run a kennel for his mentor and father-in-law Dutch Epperson. He’d already achieved some notoriety on the field trial circuit, where his ability as a trainer was recognized with a series of placements. As Delmar’s recognition grew, so did that of Ronnie Sr., who had remained on the family property in Big Cabin, training and trialing and competing in good fashion with his brother and building the kennel that bore his name on the western portion of the Smith homestead. From the kennel, the same where his son and grandchildren would later make bird dogs of their own, he trained and trialed dogs for private clients, while also training some of Delmar’s field trial prospects when time permitted. All the while, the Smith name became an increasingly common one in national bird dog circles. Through the 1960’s and 1970’s, generations of pointing dogs moved through the hands of Delmar and Ronnie Sr., and later through the hands of their sons. Building on the work and reputation of their predecessors, the younger Smith generation developed a knack for being able to take ‘problem’ dogs that were gun-shy, or man-shy, or otherwise unable to live up to their breeding, and to get them to work.

What emerged from this inculcation in bird dogs and training was a belief that a dog was a sentient being, one requiring respect and consideration, and the lessons and boundaries that any student needs. This awareness of dogs was delivered to Ronnie Smith, Jr. almost osmotically through the hours he spent, as his father had spent, tending to the animals that occupied the Smith homestead. Ronnie received a hoe and a rake and a shovel at age 5 and was directed out towards his dad’s kennels. From that tender age he spent as much time in the company of bird dogs as he did that of men. He trained his first bird dog for pay at 14, and therein learned the delight of bringing the most from a quivering mass of nose and tail and hard muscle. But underpinning that pleasure was a pride of craft and quality so essential as to go unannounced; the Smiths, for all of their generosity and grace, know what excellence is, and in their ethos there is no room for shortcutting or oversight. Ronnie Smith Jr. grew up in the shadow of giants, and it’s fair to say that hard-earned perfection was about the only benchmark he ever knew. You can see it even today in the care and time he takes with each dog.

*

I first met Ronnie Smith on the prairies of eastern Montana, where he and Susanna still run dogs on Sharptails and Huns through the month of October. In the chill of the morning he moved dogs out of the crates and into the dog boxes on the side-by-side. He settled the dogs with a firm hand on the withers and walked one at a time across the ranch road on loose lead, each dog at a heel on his left. He spotted me and turned from his work and smiled his broad smile, his eyes creasing at the corners. He extended a hand and introduced himself in a clear and unwavering Okie twang. “Pleased to meet you,” he said. “I’m Ronnie Smith.” But, like legions of bird dog folks, I knew just who he was already.

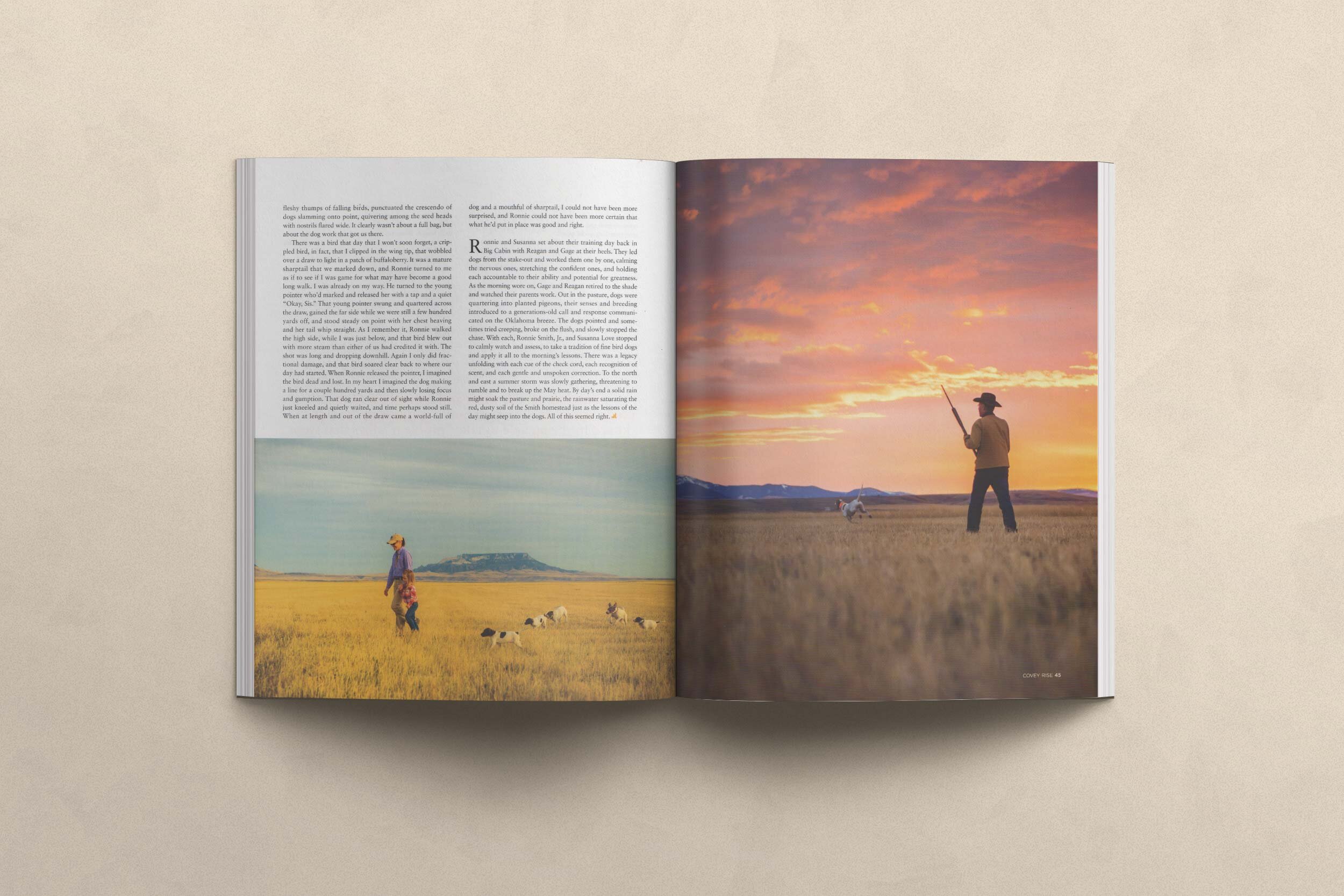

That day turned into one we will talk about for years, as we lost count of the coveys that seemed to fill the eastern Montana sky. Ronnie set down dogs in ones and two’s, steering them wordlessly, correcting them seemingly telepathically. What struck me most was the even calm and quiet of his; from his axis in the middle of the line of guns Ronnie seemed connected to each dog by an invisible string. He never appeared to disconnect and remained wholly captivated by the nuance of the game, the subtleties of the dogs action and reaction, the gentle if almost extrasensory steering that he provided from a hundred yards behind. It was as though Ronnie Smith used the dogs as a vehicle by which he too carved off slices of the prairie, assessing the whole choreography as it unfolded, and sculpting our steps and the quartering of the dogs into something of quiet, dynamic beauty. The gunshots and occasional fleshy thumps of falling birds simply punctuated the crescendo of dogs slamming onto point, quivering among the seed heads with nostrils flared wide. It clearly wasn’t about a full bag, but about the dog work that got us there.

There was a bird that day that I won’t soon forget, a cripple in fact that I clipped in the wing tip, that wobbled over a draw to light in a patch of Buffalo berry. It was a mature Sharptail, and we marked it down and well, and Ronnie turned to me as if to see if indeed I was game for what may well have become a good long walk. I was already on my way. He turned to the young pointer who’d marked and released her with a tap and a quiet “Ok, Sis…”. That young pointer swung and quartered across the draw, gained the far side while we were still a few hundred yards off, and stood steady on point with her chest heaving and her tail whip straight. As I remember it, Ronnie walked the high side and I just below, and that bird blew out with more steam than either of us had credited it with. The shot was long and dropping downhill, and again I only did fractional damage, and that bird soared clear back to where our day had begun. When Ronnie released the pointer I’d imagined the bird dead and lost, and I imagined the dog to make a line for a couple hundred yards and slowly lose focus, and gumption. That dog hove clear out of sight while Ronnie just kneeled and quietly waited, and time perhaps stood still. When at length and out of the draw came a world-full of dog and a mouthful of Sharptail I could not have been more surprised, and Ronnie could not have been more certain that what he’d put in place was good and right.

*

Ronnie and Susanna set about their training day back in Big Cabin with Reagan and Gage at their heels. They led dogs from the stake-out and worked them one by one, calming the nervous ones, stretching the confident ones, holding each accountable to their ability, and to their potential for greatness. As the morning wore on Gage and Reagan retired to the shade and watched their parents work. Out there in the pasture, dogs were quartering into planted pigeons, their senses and breeding introduced to a generations-old call and response communicated on the Oklahoma breeze. The dogs pointed and sometimes tried creeping, broke on the flush and slowly stopped the chase. With each, Ronnie Smith Jr. and Susanna Love stopped to calmly watch and assess, to take a tradition of fine bird dogs and apply it all to the morning’s lessons. There was a legacy unfolding with each cue of the check cord, each recognition of scent, each gentle and unspoken correction. To the north and east a summer storm was slowly gathering, threatening to rumble and to break up the May heat. By day’s end a solid rain might soak the pasture and prairie, the rainwater saturating the red dust soil of the Smith homestead just as the lessons of the day might seep into the dogs. All of this seemed right.

First published in Covey Rise February/March 2019