Hunting With Guides

I did not grow up in a hunting family or a hunting culture. To the contrary, in my late teens I was given the gift of hunting by a handful of men who understood how to wander New England’s forests with both a shotgun and some hope for success. These men were my first guides, though not in the typical sense. Their guidance was the elemental kind: They allowed me to wander beside them, so that I might interpret their triumphs and failures and they might make comment on my own. After a few such sessions, they determined that I was a threat to neither myself, nor the local bird population. I was then set free to do the rest of the learning on my own, and it has been by my own devices that the bulk of my hunting days have followed.

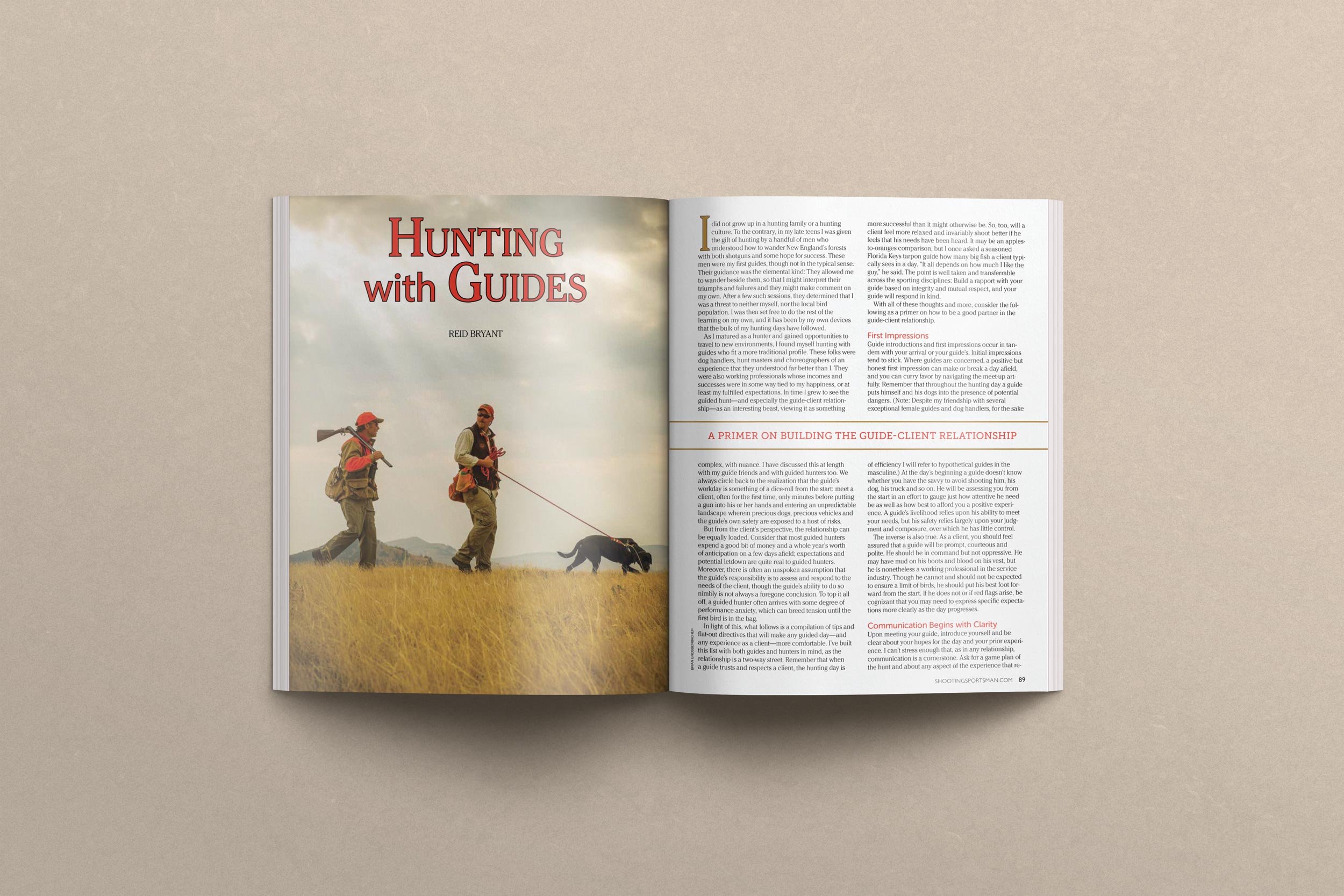

As I matured as a hunter and gained opportunities to travel to new environments, I found myself hunting with guides who fit a more traditional profile. These folks were dog handlers, hunt masters and choreographers of an experience that they understood far better than I. They were also working professionals whose incomes and successes were in some way tied to my happiness, or at least my fulfilled expectations. In time I grew to see the guided hunt—and especially the guide-client relationship—as an interesting beast, viewing it as something complex, with nuance. I have discussed this at length with my guide friends and with guided hunters too. We always circle back to the realization that the guide’s workday is something of a dice-roll from the start: meet a client, often for the first time, only minutes before putting a gun into his or her hands and entering an unpredictable landscape wherein precious dogs, precious vehicles and the guide’s own safety are exposed to a host of risks.

But from the client’s perspective, the relationship can be equally loaded. Consider that most guided hunters expend a good bit of money and a whole year’s worth of anticipation on a few days afield; expectations and potential letdown are quite real to guided hunters. Moreover, there is often an unspoken assumption that the guide’s responsibility is to assess and respond to the needs of the client, though the guide’s ability to do so nimbly is not always a foregone conclusion. To top it all off, a guided hunter often arrives with some degree of performance anxiety, which can breed tension until the first bird is in the bag.

In light of this, what follows is a compilation of tips and flat-out directives that will make any guided day—and any experience as a client—more comfortable. I’ve built this list with both guides and hunters in mind, as the relationship is a two-way street. Remember that when a guide trusts and respects a client, the hunting day is more successful than it might otherwise be. So, too, will a client feel more relaxed and invariably shoot better if he feels that his needs have been heard. It may be an apples-to-oranges comparison, but I once asked a seasoned Florida Keys tarpon guide how many big fish a client typically sees in a day. “It all depends on how much I like the guy,” he said. The point is well taken and transferrable across the sporting disciplines: Build a relationship with your guide based on integrity and mutual respect, and your guide will respond in kind.

With all of these thoughts and more, consider the following as a primer on how to be a good partner in the guide-client relationship.

First Impressions

Guide introductions and first impressions occur in tandem with your arrival or your guide’s. Initial impressions tend to stick. Where guides are concerned, a positive but honest first impression can make or break a day afield, and you can curry favor by navigating the meet-up artfully. Remember that throughout the hunting day a guide puts himself and his dogs into the presence of potential dangers. (Note: Despite my friendship with several exceptional female guides and dog handlers, for the sake of efficiency I will refer to hypothetical guides in the masculine.) At the day’s beginning a guide doesn’t know whether you have the savvy to avoid shooting him, his dog, his truck and so on. He will be assessing you from the start in an effort to gauge just how attentive he need be as well as how best to afford you a positive experience. A guide’s livelihood relies upon his ability to meet your needs, but his safety relies largely upon your judgment and composure, over which he has little control.

The inverse is also true. As a client, you should feel assured that a guide will be prompt, courteous and polite. He should be in command but not oppressive. He may have mud on his boots and blood on his vest, but he is nonetheless a working professional in the service industry. Though he cannot and should not be expected to ensure a limit of birds, he should put his best foot forward from the start. If he does not or if red flags arise, be cognizant that you may need to express specific expectations more clearly as the day progresses.

Communication Begins with Clarity

Upon meeting your guide, introduce yourself and be clear about your hopes for the day and your prior experience. I can’t stress enough that, as in any relationship, communication is a cornerstone. Ask for a game plan of the hunt and about any aspect of the experience that remains unclear to you, but also realize that there are elements that a guide cannot control. Don’t create unreachable expectations by demanding a limit of birds before the day has even begun.

If hunting out of your local area, make certain with your guide that you have the appropriate licensure for the area and species to be hunted. Be sure to clarify which species are in season and what legal bag limits are. You would hate to put yourself or your guide in the situation that occurs when an out-of-season or protected bird is inadvertently shot. Unfortunately, your guide will be on the hook as much as you will, and his licensure may be at stake.

It is a general rule of etiquette that the guide will be focused on orchestrating the hunt and therefore not hunting himself. If he sets off on the hunt carrying a gun, it is worth addressing—assuming it matters to you. You are well within your rights to request that he not do so, though if you would like for him to carry, that, too, can be communicated. If the guide plans to shoot, clarify how the bird limit will be counted, as you would hate to find yourself paying for a guided day wherein the guide shot all allowable birds or you are stuck paying for his overage. Moreover, if the guide encourages you to shoot his limit in addition to yours, clarify the legality of this and, if pertinent, don’t hesitate to communicate that you’d rather not.

Communication about physical needs and comfort is paramount. Remember that, as a guest, you have the right to move the hunt at a pace that works for you. If the guide is moving too quickly through the cover, ask him politely to slow down, or ask for a break at the end of the next windrow. If the guide is smoking cigarettes in a duck blind and it is affecting your enjoyment, feel free to ask him to stop. In short, you are the client, and the guide is at your service; your needs and wants—communicated clearly and politely—should be welcomed and, indeed, may provide greater structure for the guide’s orchestration of the day.

Safety

Any guide worth his salt will start the hunting day with a safety talk or, where it is logistically appropriate, the screening of a safety video. If this does not take place or if no safety talk is offered, ask for one. What you want to know is how the guide wishes you to move through the field (gun open or closed, how to approach dogs, and so on), which shots are appropriate and what potential hazards may await. The safety talk or willingness of the guide to present some parameters brings up an interesting point: As I said, the guide will no doubt be assessing you when you first meet, but even if you are new to the game, you should be assessing the guide as well. If safety elements aren’t addressed immediately or if the guide at any point does not seem in command of the hunt, then there is a problem. Most guides are great at sizing up their clients and will “direct” the hunt to the degree they see necessary. Some guides are less skilled in these subtleties. You are the customer; ask for clarity and for clear direction. If at any point you feel that the guide has lost command of the hunt or if safety is a concern, either you or the guide is well within your rights to call the hunt, kennel the dogs and be done.

As a final note, both parties should be aware that a competitive overtone can infiltrate the hunting day. When hunters start competing over birds shot or betting about who will be “top gun,” safety precautions can devolve quickly. Guides may assert from the start that competition stay out of the hunt day, or you as a client may be put in the position of asking hunting partners to desist from initiating any friendly rivalry. I can’t express this as a directive, but I would allow that few things strike more fear into a guide than the mention of a twenty-dollar bet.

Where Guns Are Concerned

Be certain to take the time to over-communicate about gun safety. When taking a gun from its sleeve, break it open and show the guide that it is empty. The same goes when re-casing it: Be certain to show that it is empty. If you follow this measure, you will not only garner the appreciation of your guide, but you also will inadvertently (or purposefully) get hunting partners to show you that their guns are empty too.

When walking with a closed gun, always keep the muzzles up, the safety on and your trigger finger outside of the trigger guard. When you stop to change direction, rest or reassess, open the gun immediately. This tip may sound elementary—and from an academic standpoint it is—but guides regularly tell me how frequently lifelong hunters swing muzzles past their faces or carry closed guns that point right at dogs on point. I personally have seen very expensive guns in the hands of deeply experienced hunters pointing in a direction I truly wished they weren’t.

If a bird flies over you, or between you and your partner, or flushes wild behind you and you feel that it is safe to try for it, always turn to the outside, with muzzles to the sky. If there are guns to either side of you, generally leave the bird to the flanking guns. Turning toward the centerline creates a scenario wherein muzzles might swing across the guide or other hunters. Some handlers and partners would rather never shoot at birds that flush back toward the shooters. Clarify the comfort level about this before the hunt.

Dogs

At some point either during the initial meeting or when you first get to the field, dogs likely will be let out. It is fine to ask their names and pat them on the head if they cruise by, but never feed them or give commands of any kind. Bird dogs are on the job as soon as their feet hit the ground, and they will be under the sole command of the handler. You may praise them and ask the guide about them, but do not try to assert command over them in any way. Do not call them in your direction or try to direct them into what you perceive as likely cover. Your guide will appreciate this degree of respect.

If a guide’s dogs are busting birds, hard-mouthing birds on the retrieve or otherwise misbehaving, it is reasonable to ask that the dogs be swapped out. Guides likely will know that a dog is not performing well and will be motivated to put the best dogs down in hopes of a positive result. That said, sometimes guides are tempted to run “green” dogs in order to get them some “game time.” You should be patient with this to a point, but so, too, should you feel comfortable asking for a dog swap. This can be presented as non-confrontationally as, “Could we possibly put down an older dog? I’m having trouble keeping up with this pup . . . .”

If you would like to run your own dog on a guided hunt, communicate that desire prior to your arrival. Make sure the guide understands his role in working with your dog. Would you like the guide to shoot while you handle the dog? Would you like the guide to steer you toward likely cover? Would you like the guide to run one of his dogs in tandem with yours? Again: Over-communicate, and in the case of dogs, do so well in advance of the hunt. Remember, too, that although your dog is running, the guide is still on the clock and should be compensated accordingly.

Dead Bird!

Just because you are hunting with a guide, don’t assume that he will be able to mark all of the birds. It will remain implicit that you and your guide share this responsibility. If pheasant hunting in a roosters-only area, I generally advise that hunters let the guide call the sex of birds that flush. When pushing a cornfield, over-eager hunting buddies can mistake hens for roosters and confuse other shooters. Let the guides call “Rooster!” They’ve likely seen more pheasants than most clients combined.

When a bird is shot, let the dog retrieve it, and let the guide or handler take the bird from the dog. Dog training is a continuum, and any interruption of the routine can set back a dog. The working dog is working; it needs to perform its job until the guide determines that the job is done. If the guide wants to quit on a lost bird and you’d rather keep searching, feel free to communicate your desire. Again, the guide is working on your clock, and if you would like to spend an hour in search of a cripple, you have every right to do so with the guide’s support.

Incidentally, never shoot a crippled bird on the ground or on the water without getting the OK from the guide first.

Tips & Closing Expectations

You’d be hard-pressed to find a wealthy bird guide. As in all service-oriented jobs, guides rely heavily on tips to round out what proves to be a fairly high-overhead job. Dog food, trucks, land leases and other tools of the trade are costly, and guides round out these costs with their tips. But how much is appropriate?

At the time of this writing, a good rule of thumb is to tip a minimum of $50 for a half-day hunt and $100 for a full day. Certainly an epic day might be celebrated with a bigger tip, or a dinner invitation or a piece of gear. Cash tips are preferred, though at many lodges a tip can be rolled into final payment for the whole experience. Regardless of how you intend to tip, don’t hesitate to ask your guide how he’d prefer to receive tips. This conversation also clarifies that you understand that a tip is to be left and that you will attend to it.

Summary

The guided day can and should be a tremendous experience and one to be savored. That said, it is a reciprocal experience based on a relationship that is somewhat complicated. When the arrangement is managed well, a guide will go above and beyond to ensure a great day afield, regardless of how many birds are brought to bag. Think of a guide as a trusted partner instead of a hired helper. Keep communication open and expectations clear, and the guided hunt will prove itself to be a pleasure for all involved.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine