Forest For the Trees

It rained hard in the night, the drops swelling to a roar on the shingled roof. By dawn the rain had passed, but the morning remained heavy and wet, and the sky seemed to hang low among the treetops. The potholes in the camp road were full to overflowing. I walked along the roadside berm and stopped beside the first of the puddles, and used the toe of my boot to move a slick of floating leaves to the edge. I was careful not to roil the mud. A few dozen earthworms lay against the bottom in the cold, standing water. They were dead of course, having turned rubbery and fleshy pale, their shallow tracks still visible where they’d tried to outpace the rising rainwater. Somewhere in the night they had been overtaken, perhaps as much by the rain as by the advancing season. They had, I supposed, become little casualties of the last cold rainfall before the snow. This struck me as a fitting bit of punctuation. Like the leaves and the bent meadow grasses, the worms had long since been overwhelmed by the richness of sun and summer soil. Now, with Autumn fading fast, they’d become distended, lost their blush and animation, and turned over to decay. Whatever remained to face the winter here would need to be made of sturdier stuff, of denser bone and stronger gristle.

A raven crawked somewhere in the hedgerow.

He’d no doubt make it through.

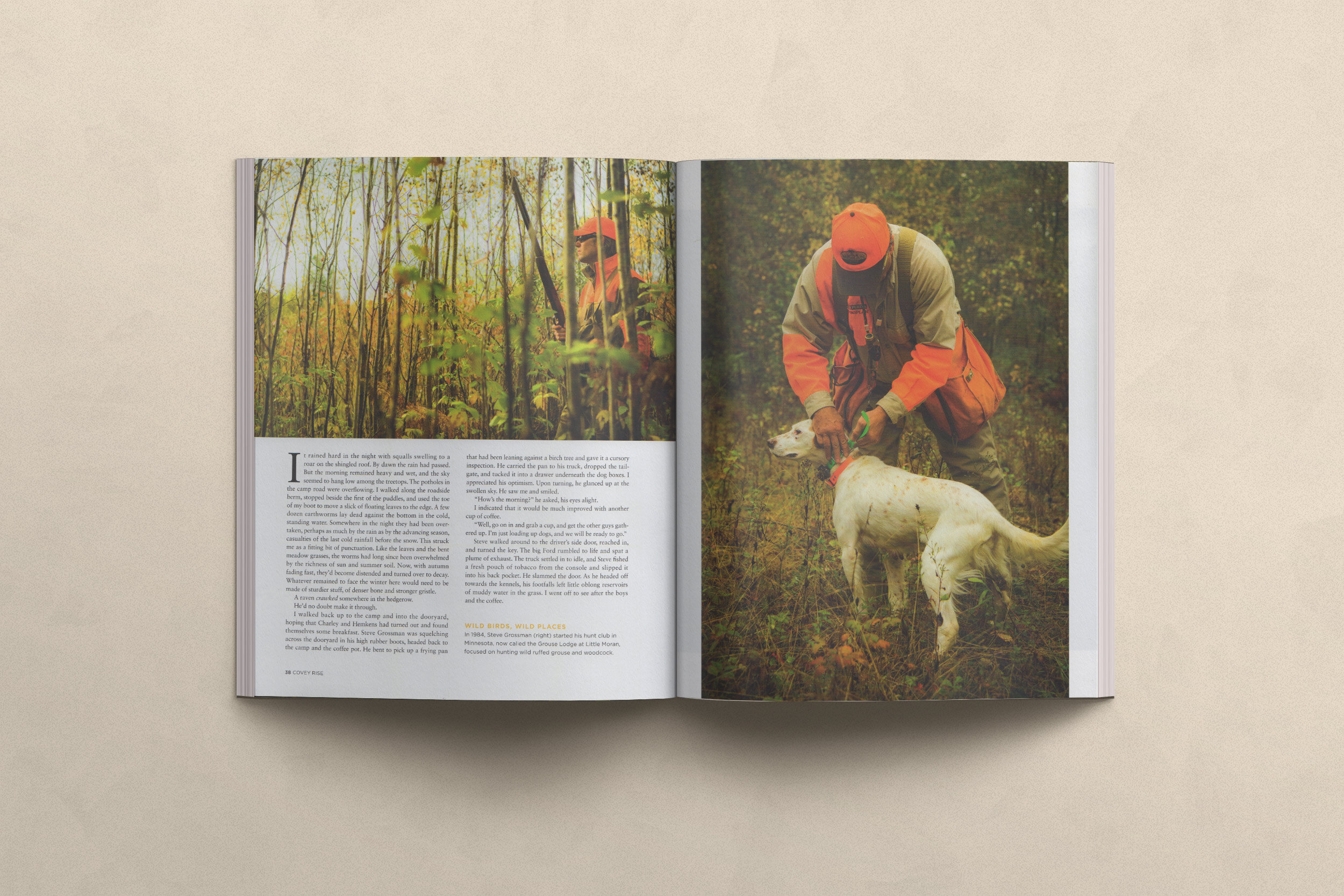

I walked back up to the camp and into the dooryard, hoping that Charley and Hemkens had turned out and found themselves some breakfast. Steve Grossman was squelching across the dooryard in his high rubber boots, headed back to the camp and the coffee pot. He bent to pick up a fry pan that had been leaning against a birch tree, and gave it a cursory inspection. He carried the pan to his truck, dropped the tailgate, and tucked it into a drawer underneath the dog boxes. I appreciated his optimism. Upon turning, he glanced up at the swollen sky. He saw me and smiled.

“How’s the morning…” he said, his eyes alight.

I indicated that it would be much improved with another cup of coffee.

“Well, go on in and grab a cup, and get the other guys gathered up… I’m just loading up dogs and we will be ready to go.”

Steve walked around to the driver’s side door, reached in and turned the key. The big Ford rumbled to life, and spat a plume of exhaust. A shot of warm air from the heater fogged the windshield. The truck settled in to idle, and Steve fished a fresh pouch of tobacco from the console and slipped it into his back pocket. He slammed the door. As he headed off towards the kennels, his footfalls left little oblong reservoirs of muddy water in the grass. I went off to see after the boys and the coffee.

*

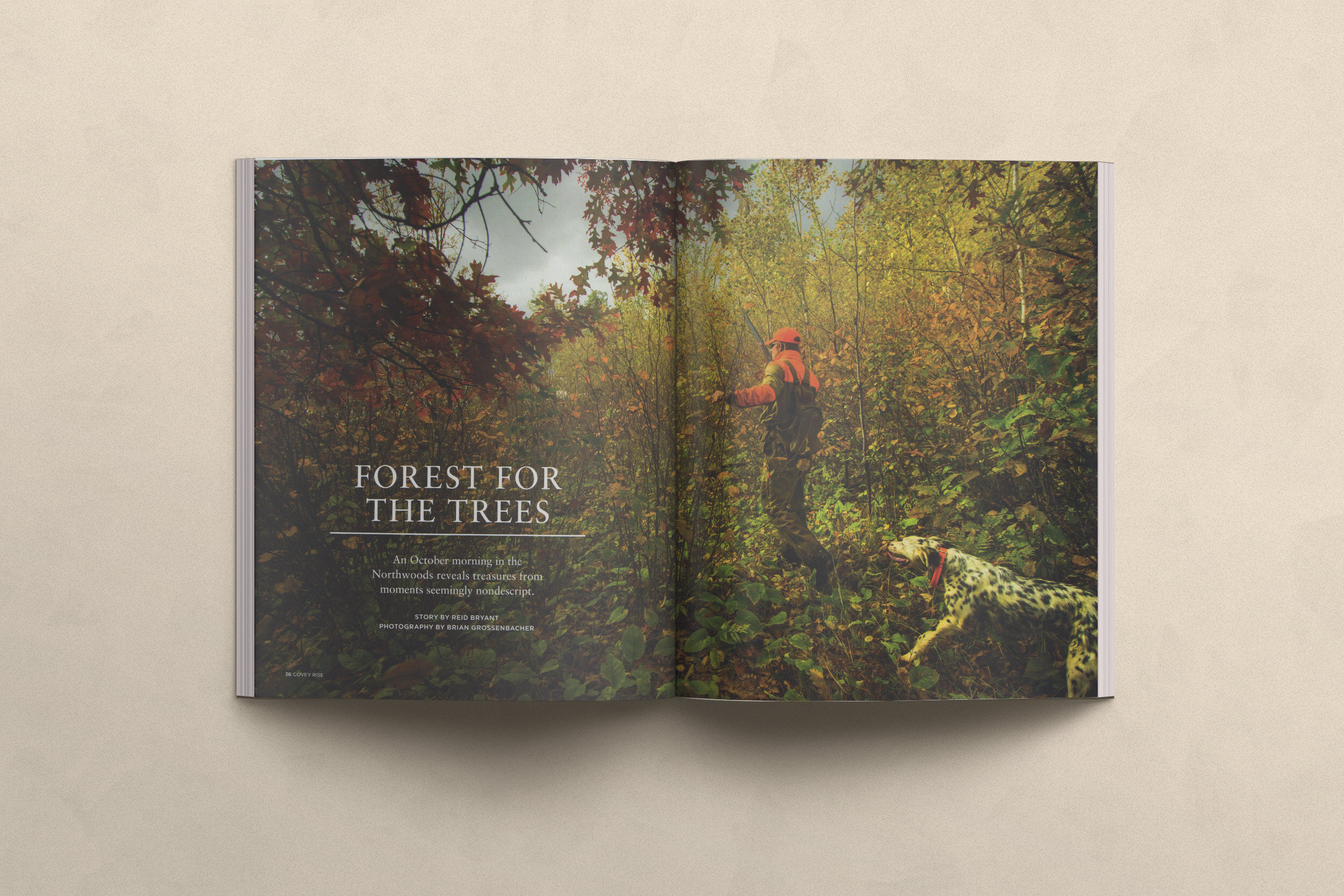

With mugs in hand and dogs loaded and a fresh pouch of tobacco to share, we took the hard right turn out of Little Moran and onto the tar road. The morning was saturated grays, the sky flattening the shimmer of the popple whips and the streaked gunmetal of the water-stained asphalt. Steve fiddled with the radio dials. In the town of Staples proper we clattered over the train tracks and banked north into the outlying country of farms and broken timber. The big hayfields had long since seen their last mowing, and the odd remaining bales were discarded bits of summer fading fast, likely too full of thistle and sticks to warrant wrapping. We turned a hard right and thumped along at a clip, twisting deeper into that patchwork place. A few miles on we left the tar road behind. The wet substance of the morning and the low-slung trees and October itself seemed to swallow us up and shut its maw, and we found ourselves engulfed by grouse cover defined. Along the roadsides the tangle began, meadows grown over into high-bush cranberry and brambles and hummocks of grass, and a barricade of pole-sized hardwood beyond. Popple leaves, faded yellow and crinkly, covered the dirt two-track. Somewhere in the thick of it, Steve slowed and turned and tucked the Ford into the head of a logging trace. He shut off the engine. The cover around us soaked up the sound as the truck sighed and settled in the way trucks do, and everything got still. The dogs in their boxes started to whine. Steve filled his cheek, and offered us the pouch.

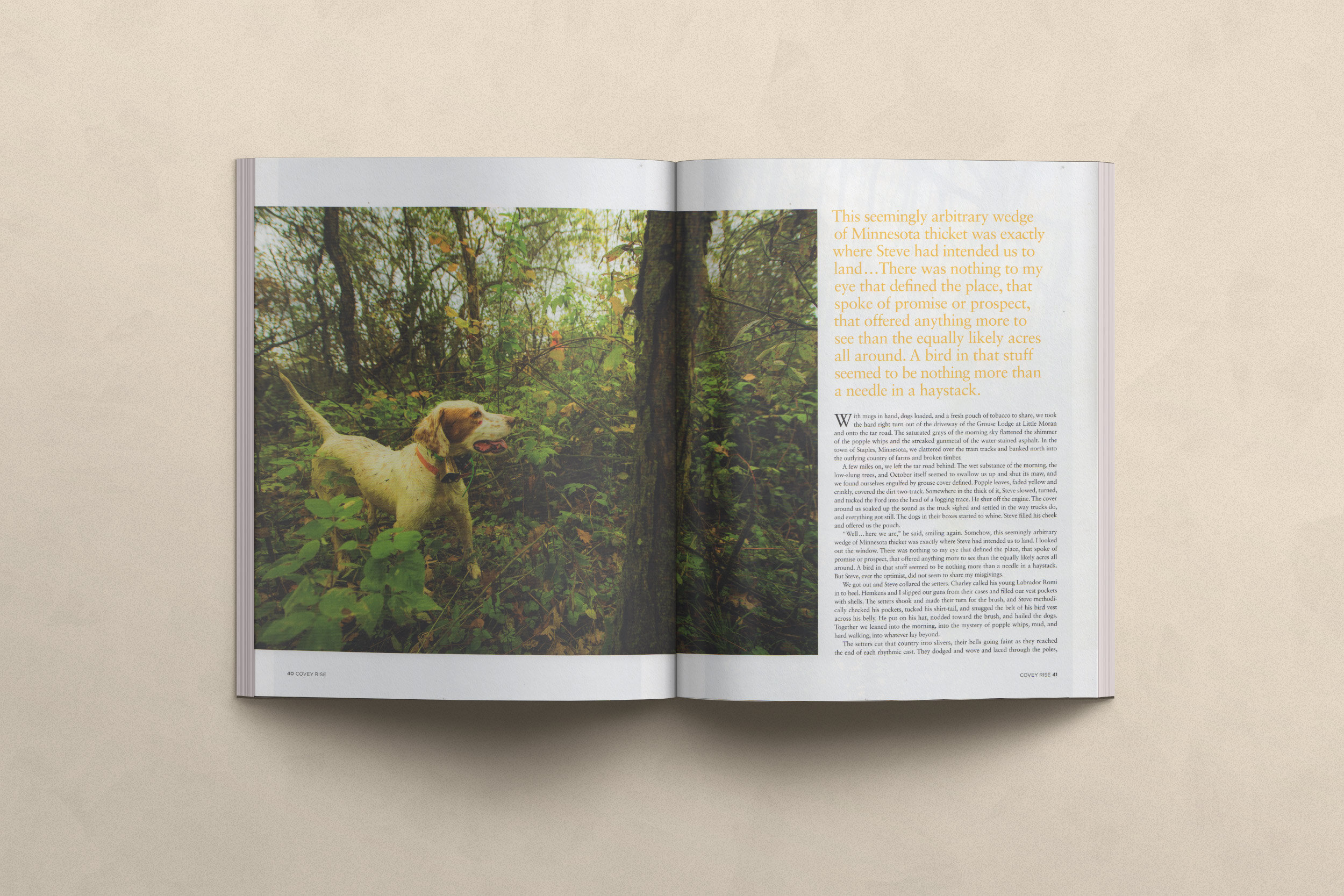

“Well… here we are,” he said, smiling again. Somehow, this seemingly arbitrary wedge of Minnesota thicket was exactly where Steve had intended us to land. I looked out the window. There was nothing to my eye that defined the place, that spoke of promise or prospect, that offered anything more to see than the equally likely acres all around. A bird in that stuff seemed to me nothing more than a haystack needle. But Steve, ever the optimist, did not seem to share my misgivings.

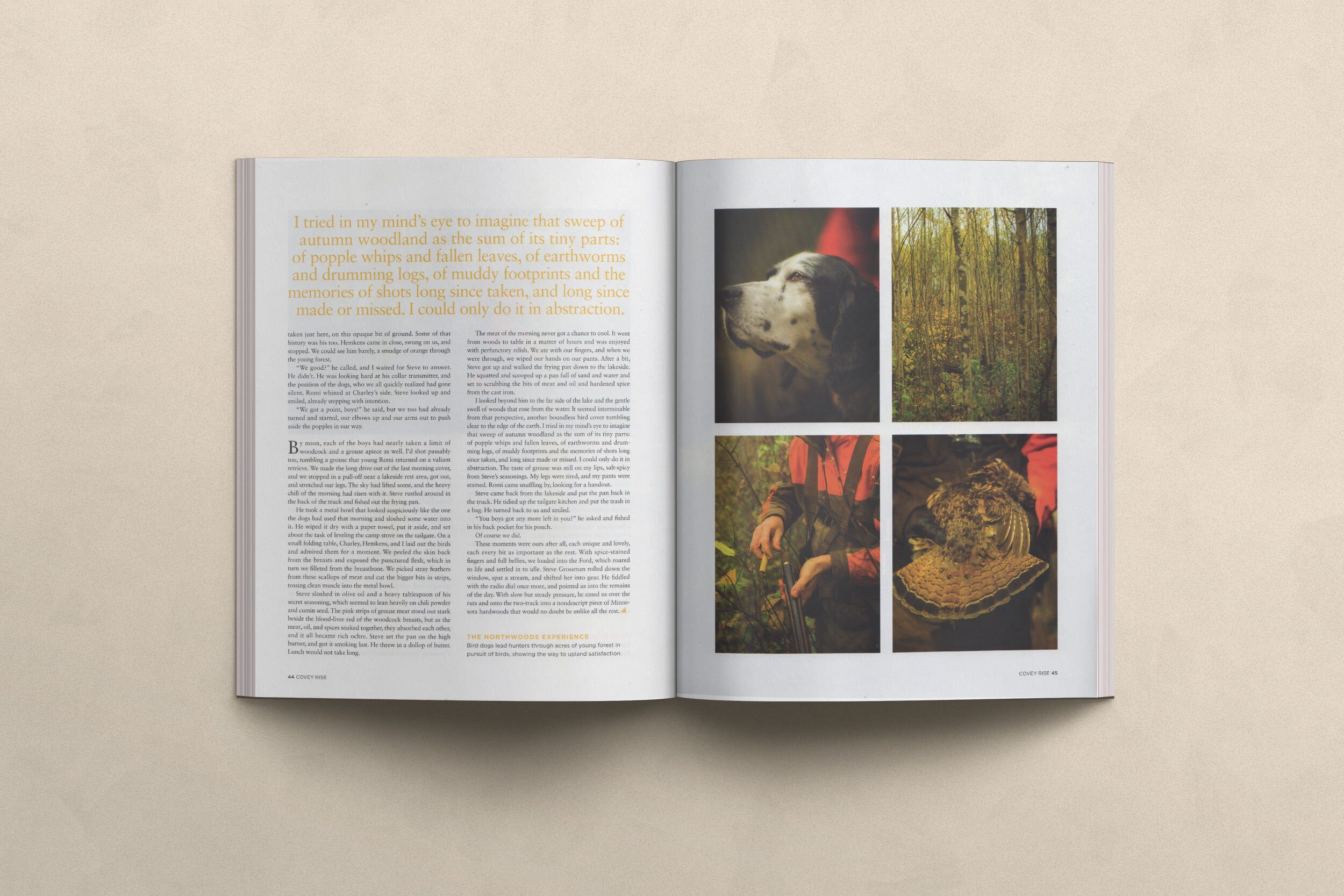

We got out and Steve collared the setters, and Charley called his young Labrador Romi in to heel. Hemkens and I slipped our guns from their cases and filled our vest pockets with shells. The setters shook and made their turn of the brush, and Steve methodically checked his pockets, tucked his shirt-tail and snugged the belt of his bird vest across his belly. He put on his hat, nodded toward the brush, and hailed the dogs. Together we leaned into the morning, into the mystery of popple whips and mud and hard walking, into whatever lay beyond.

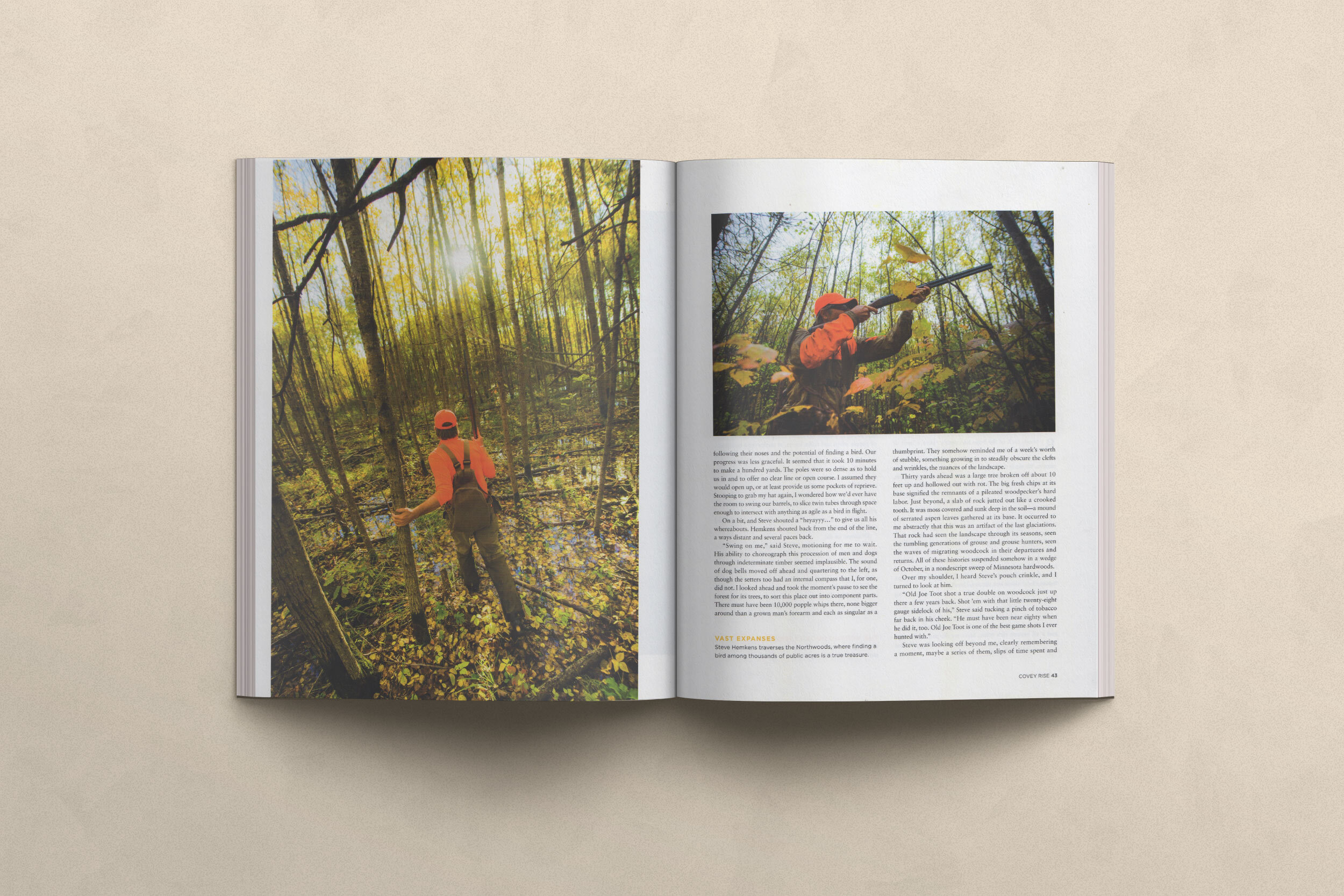

The setters cut that country into slivers, their bells going faint as they reached the end of each rhythmic cast. They dodged and wove and laced through the poles, following their noses and the potential of a bird. Our progress was less graceful. It seemed it took ten minutes to make a hundred yards. The poles were so dense as to hold us in, and to offer no clear line or open course. I assumed they would open up, or at least provide us some pockets of reprieve. Stooping to grab my hat again, I wondered how we’d ever have the room to swing our barrels, to slice twin tubes through space enough to intersect with anything as agile as a bird in flight.

On a bit, and Steve shouted a “heyayyy…” to gave us all his whereabouts. Hemkens shouted back from the end of the line, a ways distant and several paces back.

“Swing on me,” said Steve to Hemkens, motioning for me to wait. His ability to choreograph this procession of men and dogs through indeterminate timber seemed implausible. The sound of dog bells moved off ahead and quartering to the left, as though the setters too had an internal compass that I for one did not. I looked ahead, and took the moment’s pause to see the forest for its trees, to sort this place out into component parts. There must have been ten thousand popple whips there, none bigger around than a grown man’s forearm, each as singular as a thumbprint. They reminded me somehow of a week’s worth of stubble, something growing in to steadily obscure the clefts and wrinkles, the nuances of the landscape. In doing so, however, they perhaps provided nuances of their own, softened edges, depth and shadow that had not been there, that would deepen with age and maturity. Thirty yards up was a large tree broken off ten feet up and hollowed out with rot, the big fresh chips at its base the remnants of a Pileated woodpecker’s hard labor. Just beyond, a slab of rock jutted out like a crooked tooth. It was moss covered and sunk deep in the soil, a mound of serrated aspen leaves gathered at its base. It occurred to me abstractly that this was an artifact of the last glaciations, a witness to this land through time to the old tree’s birth and degradation, to the youth and zealous abundance of young popple. That rock had seen the landscape through its seasons, seen the tumbling generations of grouse and grouse hunters, seen the waves of migrating woodcock in their departures and returns. All of these histories suspended somehow in a wedge of October, in a nondescript sweep of Minnesota hardwoods.

Over my shoulder, I hear Steve’s pouch crinkle, and I turned to look at him.

“Old Joe Toot shot a true double on woodcock just up there a few years back. Shot ‘em with that little twenty-eight gauge sidelock of his.” Steve tucked a pinch of tobacco far back in his cheek. “He must have been near eighty when he did it, too. Old Joe Toot is one of the best game shots I ever hunted with.”

Steve was looking off beyond me, clearly remembering a moment, maybe a series of them, slips of time spent and taken just here, on this opaque bit of ground. Some of that history was his too. Hemkens came in close, and swung on us, and stopped. We could see him barely, a smudge of orange through the pecker poles.

“We good?” he called, and I waited for Steve to answer. He didn’t. He was looking hard at his collar transmitter, and the position of the dogs, who we all quickly realized had gone silent. Romi whined at Charley’s side. Steve looked up and smiled, already stepping with intention.

“We got a point, boys!” he said, but we too had already turned and started, our elbows up and our arms out to push aside the popples in our way.

*

By noon, Hemkens had shot his little Beretta to great effect, and had taken a limit of woodcock. Charley had only one to go. I’d shot passably too, tumbling a grouse that presented a hard left crosser, shooting it well enough but not killing it soundly. We’d had to call in young Romi, who made good on a valiant retrieve.

Each of the boys had taken a grouse apiece as well.

We made the long drive out of the last morning cover and along the lee shore of Clam Lake, and we stopped in the pull-off there, got out and stretched our legs. The day was still overcast but the sky had lifted some, and the heavy chill of the morning had risen with it. In the gravel track just off the lakeside, what had remained of the standing water had soaked back into the earth, leaving soft, tracked mud in the hollows. No doubt the robins, soon to head south, had been grateful for the simple gifts of the earthworms and the easy pickings they presented.

Steve rustled around in the back of the truck and fished out the fry pan. He took a metal bowl that looked suspiciously like the one the dogs had used that morning and sloshed some water into it. He wiped it dry with a paper towel and set it aside, and set about the task of leveling the camp stove on the tailgate. On a small folding table, Charley, Hemkens and I laid out the birds and admired them for a moment. The recent ones were still limp and loose, the flesh and feather living-warm to the touch. We peeled the skin back from the breasts and exposed the punctured flesh, which in turn we filleted from the breastbone. We picked stray feathers from these scallops of meat and cut the bigger bits in strips, tossing clean muscle into the metal bowl. Steve sloshed in olive oil, and a heavy tablespoon of his secret seasoning, which seemed to lean heavily on chili powder and cumin seed. The pink strips of grouse meat stood out stark beside the blood-liver red of the woodcock breasts, but as the meat and the oil and the spices soaked together, they absorbed each other, and it all became rich ochre. Steve set the pan on the high burner, and got it smoking hot. He threw in a dollop of butter. Lunch would not take long.

The meat of the morning never got a chance to cool. It went from woods to table in a matter of hours and was enjoyed with perfunctory relish. We ate with our fingers, and when we were through we wiped our hands on our pants. After a bit, Steve got up and walked the frying pan down to the lakeside. He squatted and scooped up a pan full of sand and water, and set to scrubbing the bits of meat and oil and hardened spice from the cast iron. I looked beyond him to the far side of the lake, and the gentle swell of woods that rose from the water. It seemed interminable from that perspective, another boundless bird cover tumbling clear to the edge of the earth. I tried in my mind’s eye to imagine that sweep of Autumn woodland as the sum of its tiny parts: of popple whips and fallen leaves, of earthworms and drumming logs, of muddy footprints and the memories of shots long since taken, and long since made or missed. I could only do it in abstraction. The taste of grouse was still on my lips, salt-spicy from Steve’s spice mix. My legs were tired, and my pants were stained. Romi came snuffling by, looking for a handout.

Steve came back from the lakeside and put the pan back in the truck. He tidied up the tailgate kitchen, and put the trash in a bag. He turned back to us, and smiled.

“You boys got any more left in you?” he asked, and fished in his back pocket for his pouch.

Of course we did.

And so we stood and stretched, loaded Romi into her box and replaced our spent shells with full ones. These moments were ours after all, each unique and lovely, each every bit as important as the rest. With spice-stained fingers and full bellies we loaded into the Ford, which roared to life and settled in to idle. Steve Grossman rolled down the window, spat a stream, and shifted her into gear. He fiddled with the radio dial once more, and pointed us into the remains of the day. With slow but steady pressure, he eased us over the ruts and onto the two-track into a nondescript piece of Minnesota hardwoods that would no doubt be unlike all the rest.

First published in Covey Rise