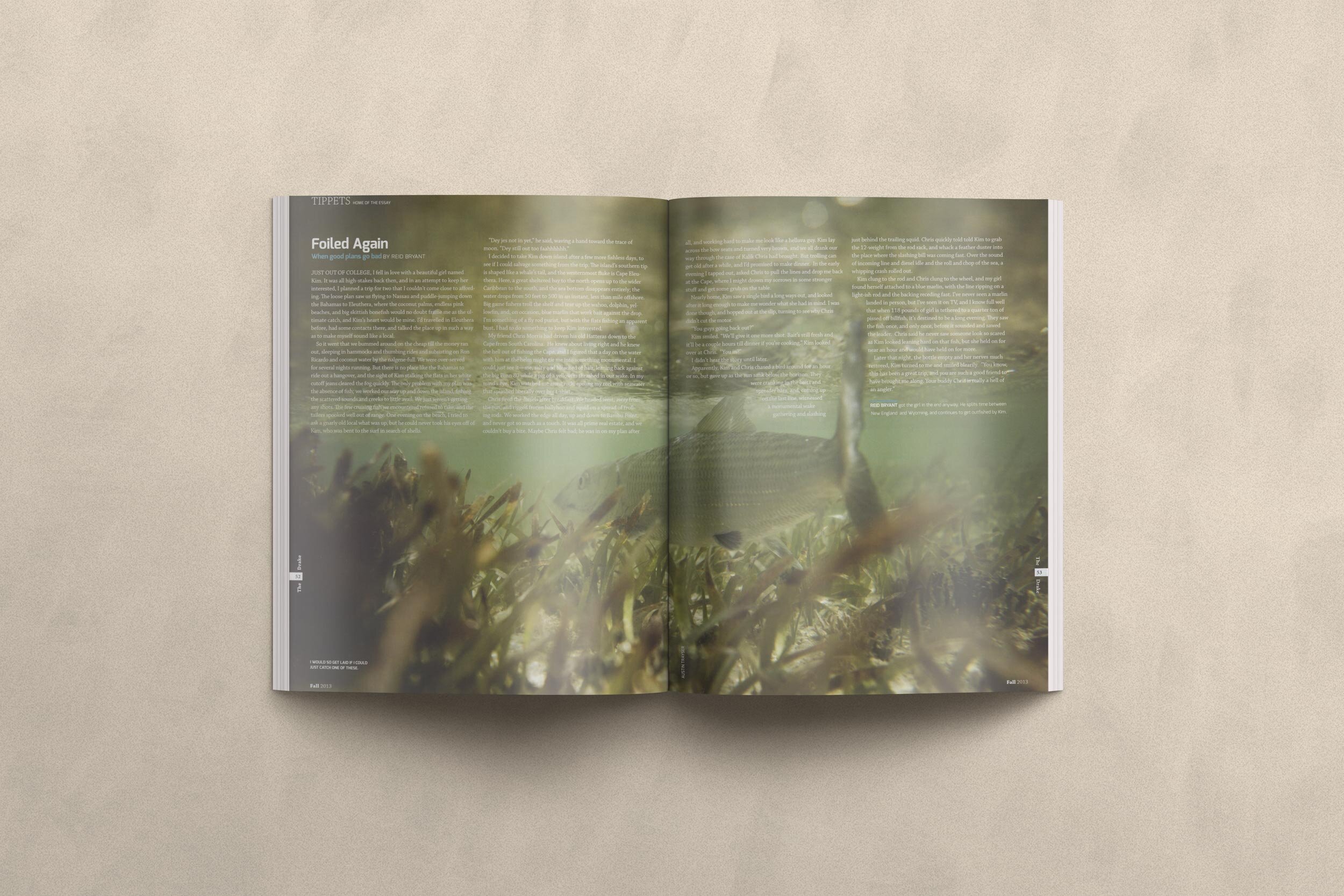

Foiled Again

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

The above quote by Aldo Leopold alludes knowingly to what remains essential about being a hunter. Central to the process of becoming a hunter, and central to the identity found upon arrival, is the community that Leopold speaks of. This is not just a community of peers, but a community of all things in nature. When I became a hunter, I ceased to walk over the land; as a hunter, I became an element of that land, a cog in a remarkable living machine that is as old as the earth itself, and as timeless. Leopold spent a career reflecting on this community, and the role of humans within it. He sat and he watched “like a mountain,” and he learned by reflective observation. He also took up a gun each autumn and went hunting, and learned a bit more about himself, and his human ecology, than he’d known before.

Aldo Leopold went on to assert that “in short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.” This construct is somewhat hard to grasp for most folks, simply because humans have the capacity, the resources, the vision, and the ingenuity to assert dominance over a natural system at will. We do so each and every day, as we increasingly live outside of nature. It is why we have survived and flourished, and it is also why, you might say, we have become disenchanted with, and certainly disconnected from, our natural world. We have lost our place in the community that allowed us a sense of place since time immemorial, and we’ve in turn become confused with our role.

It is ironic, therefore, that taking up a gun in Fall and shooting a bird or a deer might serve to re-establish a fundamental philosophical and ecological order. It is ironic that deploying a man-made machine and ostensibly asserting dominance over a wild creature, or even more paradoxically a non-endemic, one-time-stocked creature, could help me regain a sense of myself. It is most ironic, I might add, that in light of the availability of pre-packaged, pre-cooked, profoundly inexpensive food I would ever choose to spend time and money shooting at a piece of meat that, more often than not, disappears unscathed into the backdrop. But I do this, and I love it, and I seek to do it again. In turn, it makes me care a little more about the creatures I seek, and the places in which I seek them.

I am neither a student of psychology nor a student of philosophy, so I can’t authoritatively say why I am drawn to hunting, or what it means that I am compelled in this way. I assume that humans were hunters for so long that it became a part of our wiring, and only fairly recently did we disconnect from a personal relationship with food acquisition. I can say, and with some confidence, that in becoming a hunter, I was afforded an awareness of a new community, or perhaps better stated, a forgotten community, and one that my ancestors knew well. My friend Kurt Rinehart, who is one of the finest naturalists I know, often says that in being a hunter, he is offered a seat at the table. I love this analogy, in that it is resonant on a level that both speaks to basic human need, and to essential human consciousness. As a hunter, in North America anyway, your table is laid with a host of wild foods so delicate and rare that they are, in themselves, great treasures. These foods are offered in quantity for the cost of a hunting license, and some wonderful days spent afield. Beside you at the table are people who, like you, see some value in being outdoors, in taking responsibility for a linear connection to the food they eat, and the realities of it. There is a shared identity at the table, and a shared pride of place. There is, at root, community. But a seat at the table offers far more lasting value than simply a fine piece of meat, served in good company.

When I became a hunter, I attained a vested interest. My very identity became reliant upon the nourishment of a species, the preservation of access, the maintenance of legislation that allows me to pick up a gun and go looking for a bird to shoot. In becoming a hunter I learned to be a part of a bigger construct, one in which animals rise from habitat, and I, also a piece of the habitat, aim to harvest them. In this construct, I match my skills against a bit of nature, and I witness unpredictability. I begin to notice things I rarely noticed before; the crackle of turning leaves on an October afternoon, the smell of prairie wheat, the glint of a cottonwood grove. These became things synonymous with my identity, and I began to care for and about them more. When that new office building threatened my pet woodcock covert, I took notice. When an unknown blight did in my precious quail, I threw some money towards land stewardship and avian research. I became a part of a community that hinged on my involvement and investment. Without my care that community would suffer an incremental blow.

In short, hunting connects me, in a visceral way, to something of value. That something is a layer-cake of resources, natural and otherwise, that I suddenly see as a part of my personal geography. As a hunter, I begin to rely on those resources to provide me with a sense of place, a sense of self, and a sense of belonging. Within said community I am a member alongside the game, and the cover, and the greater ecosystem. I truly become a citizen of what Aldo Leopold called a land-community. As a citizen I am a stakeholder, one with both rights and obligations.

I firmly believe that in hunting, I cannot help but learn to become a better steward of the land and the critters that exist upon it. As a hunter, I am reminded that we humans are but one species of those critters, albeit with a bit more firepower and impact than most others. As a hunter I am out with my feet on the ground, gaining intimacy with the land-community in a way I otherwise could not. I become, as poet Marge Piercy once described, “a native of that element.” I revisit this land community with a hunter’s eyes, and an acute awareness that the experience I seek hinges on the health of that community. I pull my seat up to the table and I care deeply about who is in attendance, and what is being served. In the absence of this intimacy, conservation becomes something remote and academic. In the presence of this intimacy, with blood beneath my fingernails and mud on my pant cuffs, it becomes something well worth fighting for.

First Published in The Drake.