Feathers and Followers

There is a guy out there named Shawn Wayment who, on a recent ptarmigan hunt, dinged the muzzle of a favorite bird gun. I feel bad for Shawn, bad about the damage, and bad about the emotional dilemma that arises when a lovely gun takes an honest and hard-earned blow, but remains a little bit broken. I’ve invested some empathy in this particular case because I like Shawn; he’s a guy that in many ways is much like me, though his guns are a bit more dinged up (sorry buddy). He lives in Colorado and spends his workaday life as a veterinarian, and around the edges he chases wild birds, and blue quail in particular, with an ardor that is real and lovely and inspiring. He prefers lively setters and Damascus barrels and green chilis on his eggs. Oddly enough, despite our sentiment of friendship I can’t really claim to know Shawn; we’ve never shared a wood fire, or bragged on each-others’ dogs, or swirled and swallowed one bourbon too many after a long walk together in good country. We’ve spoken on the phone, exchanged some notes, and that’s about it. What I know of him, and frankly how I’ve derived an opinion of him, has been via his blog (Uplandways.com) and Instagram feed (@birddogdoc). The more I think about that, the more it seems an altogether superficial way in which to ‘know’ a guy with whom I share a deep-seated and resonant identity as a bird hunter. I’m grateful nonetheless.

There are other folks out there in the digital ether who inhabit a similar niche, and with whom I share a similar kinship. There are the boys from Mouthful of Feathers, whose blog I follow and whose writing I aspire to from 3000 miles away. There is Jillian Likiuski, The Noisy Plume herself, whose curated moments afield are as beautiful in on Instagram as anything built up in oils on a textured canvas. There is Ronnie Boehme, whose Hunting Dog Podcast provides a global podium from which a talented storyteller and an avid hunter/dog handler can learn and teach and share. In all of these people and the platforms they choose I find common ground, as I am afforded the chance to see the substance of their experience, and they are afforded the infinite opportunity to share it. On a phone, laptop, or tablet I can see and hear and smell and taste their stories unfolding, see their moments presented in near real-time and technicolor, feel the very grain of what inspires them. This is a wonderful thing. At least I think it is…

As I look back over a life in upland bird hunting, I have a certain warmth for the handful of friends with whom I’ve shared my days afield. By and large these were folks who I met in that intuitive and linear (if sometimes serendipitous) way that the communion of bird hunters takes place. I hunted often with my pal Matt Breuer who I met in school, and so too with my college professors Dave Brown and Dave Linck. There was old Dick Coffin, my ridge-top neighbor for a decade, who I met on account of the setters and springers that wandered out of his barnyard to slow the passing traffic. And in more recent years I’ve been graced with a wonderful group of co-workers whose careers in outdoor writing and travel have, like mine, greatly narrowed and enriched the shared pool of hunting companions. But so too have I spent many, many seasons feeling a bit like an island, a guy out there running a dog through something of a bygone tradition, a sporting heritage that was fast fading into the sepia tones of memory. For much of my experience as a bird hunter, my communion was not held on the tailgate but around the expressions of recognizable moments and stories trapped in time and communicated in written word and watercolor. The art and writing of a bird hunting life gave me hope that indeed there was a brother and sisterhood out there of which I was a part, even if that community was in the past, or representative, or otherwise remote to me. But then, I still felt some degree of isolation, wishing for a few good pals with whom to share my brag-dog stories, and the recollections of great shots, and heroic misses. And then came social media, and everything changed in the relative blink of an eye.

Increasingly over the past decade, or maybe markedly less, bird hunters have discovered social media, and expressive opportunities have become far more democratic. This new platform has made the expression that enhances our bird hunting broader, with input from exponentially more folks who both love the upland lifestyle, and love to share it. We now all have access to the same publishing house, and the same wall space in the world’s largest gallery. But so too has this broadening of our expression impacted the way in which we celebrate bird hunting, how we communicate the images of our days afield, and how we catalog our stories. It began in dribs and drabs: bloggers writing of their days afield, grainy Youtube videos shared around of a flushing bobwhite crumpling in mid-flight, the occasional Facebook page denoting a user’s impassioned love for the upland game. But as with all things digital, the rise in bird hunting exposure has become meteoric, exposing a greater community of upland hunters than I for one ever thought existed. This exposure, and this platform for community and communication, should perhaps not come as a surprise; after all, what social media affords the modern bird hunter is defined in its very name. Social media is social. It offers us a wonderful community of people whose expressions we relate to, and who are relatable as individuals too. All of a sudden, we know about the dinged barrels that befell a man on the opposite side of the country, a man who we know likes green chilis on his eggs. We can relate to the sunset shots and the short-form stories of our hunting brethren and so too can we share ours. What tailgate moments we miss in person we can re-create with the sweep of a thumb, and somehow this makes sense to me, and fills me up with hope.

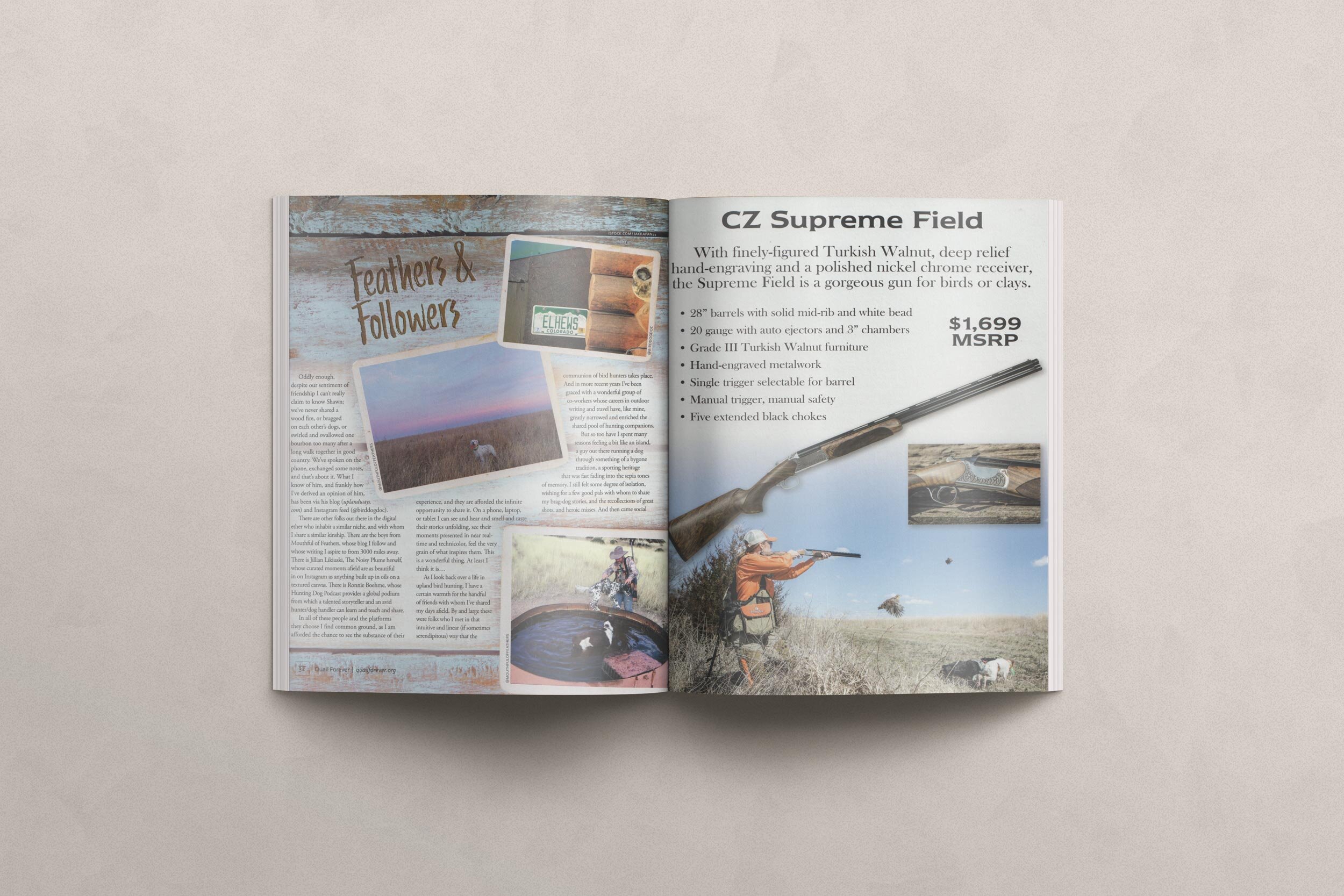

But as with all things, there is a potential down-side too. As I look out upon the changing face of bird hunting, the community it engenders, and the expressive mediums that celebrate it, I see a bright future informed by a heritage-laden past. When I look at my bird hunting I see a collection of precious moments filled with suspense and suspended animation, and the search for something designed to be well hidden. I see dogs I have loved and friends I have walked beside and lost, and guns a century my junior that will last a century more. I also see a tradition of celebrating a bird-hunting identity that leaned on written word and watercolor, on engraved side-plate metal and cast bronze. I see a tradition of capturing with some degree of permanence the artistry of dogs, the beauty of guns that are hand-made and cherished, and the moments during which we turn both to their purpose with visceral intention. I see a reliance on expression that does not exist in other pursuits, at least not with the precision that we see within the context of bird hunting and bird hunters. When I’ve felt somewhat isolated in my reverence for bird hunting, felt myself missing a community of like-minded folks to share that reverence with, I turned to Ruark and Ripley, whose work reminded me that others felt the same, and took it all just as seriously. This too gives me hope.

The conundrum of social media as it pertains to bird hunting stems from the fact that the digital space is built for rapid-fire consumption. It is, by nature, impermanent, allowing us to see a precious moment and then to see it quickly superseded by the next. An Instagram story that describes a pup’s first solid point should be worthy of a journal entry, or a framed photo, or at the very least a phone call to a good friend who would appreciate such a thing. A dewdrop and pine-scented Georgia morning deserves the mastery of Ripley’s watercolor, I think we’d all agree. But with social and digital media we get immediate candy coating and then the next thing, and somehow it feels that our bird hunting should be worthy of more. Call me a nostalgic, but I still feel my moments afield are worth remembering with a frame or a leather binding, something that celebrates an identity and a handful of memories afield that are equally worthwhile. At the very least they deserve an hour and a hardwood fire and a belt of bourbon with a friend.

So therein lies the rub. As I sit here on my little perch with one eye towards the past and one I towards the future, I suppose I am conflicted a bit by the dynamic and very real present. I love that I know about Shawn Wayment’s preference for Mexican food, and I love that I had a pang of empathy when I saw a picture of the poor guy’s dinged barrels. I love that in the images he posts and the comments he shares I find recollections of my own great days, my own adventures and misadventures. I love that in a workday meeting I can secret my phone beneath the tabletop and scroll through a volume of friends and their moments, their covey rises and birds-in-hand, their new pups and old doubles. In this communion there is that universal resonance that both art and kinship make possible. Problem is, in this increasingly digital world, it feels like those shared moments are all too fleeting, and lacking in essential gravity.

I suppose in the end I am fortunate. As Gen-X bird hunter, I have bit of gray in my hair and a bit of gimpiness in my knees, and enough days afield to have some curmudgeonly opinions. I also remember polaroid film and carbon paper, if that dates me sufficiently. That said, I like to think I’m still somewhat sensitive to, and excited about, the rapidly changing world in which I live. I too have been blessed to consider myself a bird hunter, and to know the weight and pride of that identity. With social media I have come to know the pleasure of a kinship, a vitality, a sense of dynamic energy within the sport I love. With Instagram and Facebook and social media in general, I have come to identify a cadre of sleepers out there who still maintain a few pointers and favor light 16 ga. doubles, and who love the aesthetic of the upland life. That we have suddenly found a common ground, and a place to share that passion, is a gift. But never will my moments afield be suitably celebrated with an Instagram story or a Facebook post; I’ll share them for sure and put them out there in the ether for my far-flung friends to see and scroll on past, but I’ll always want my bird hunting to be rooted in real soil. A good old fashioned tailgate beer, a long winter evening with a dog-eared Babcock, or simply a morning look at the Ripley print that hangs above my bed… those are the are the things of flesh and spirit that will never be replaced, or digitized, or improved.

First published in Quail Forever Magazine