(dis)Comfort Food

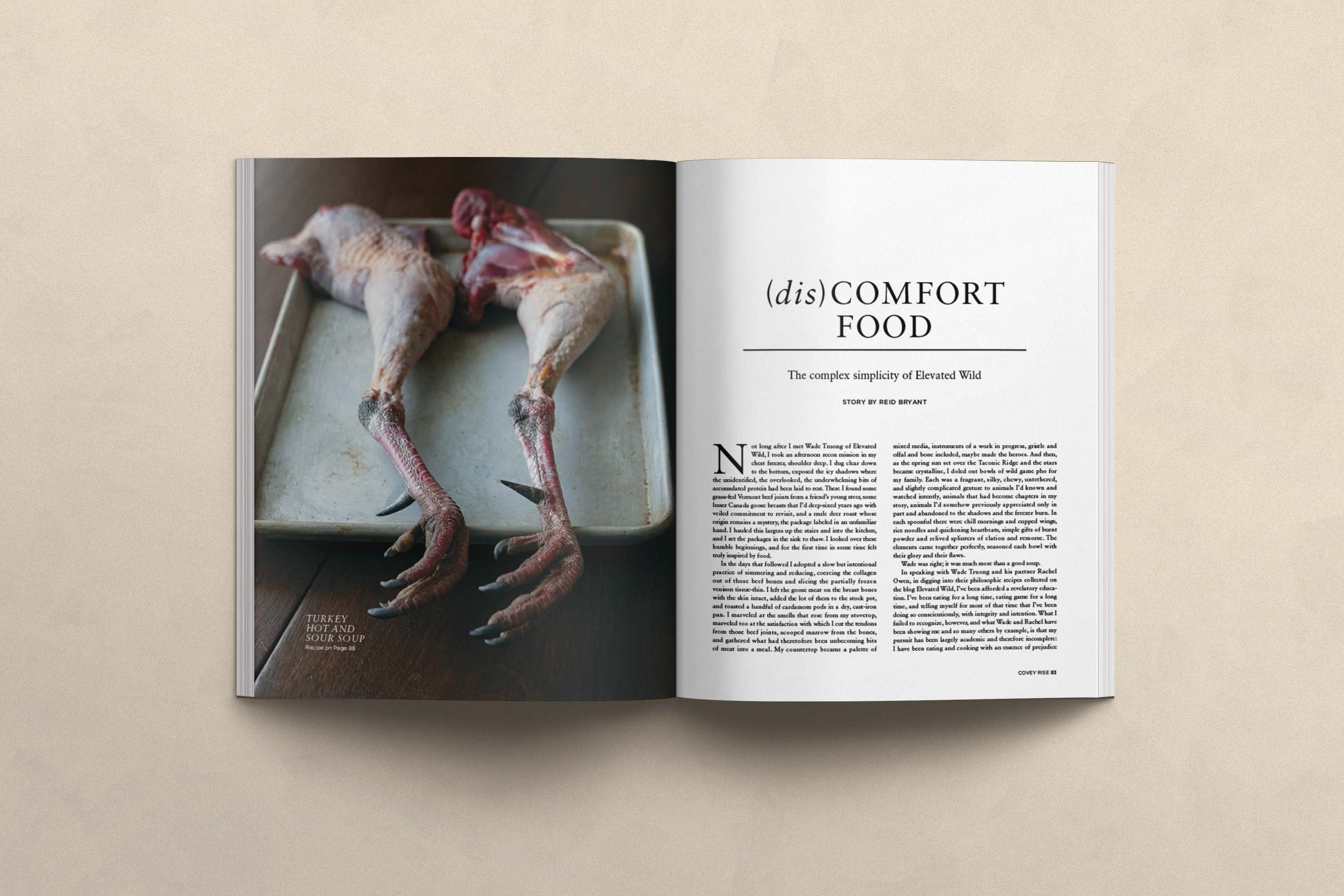

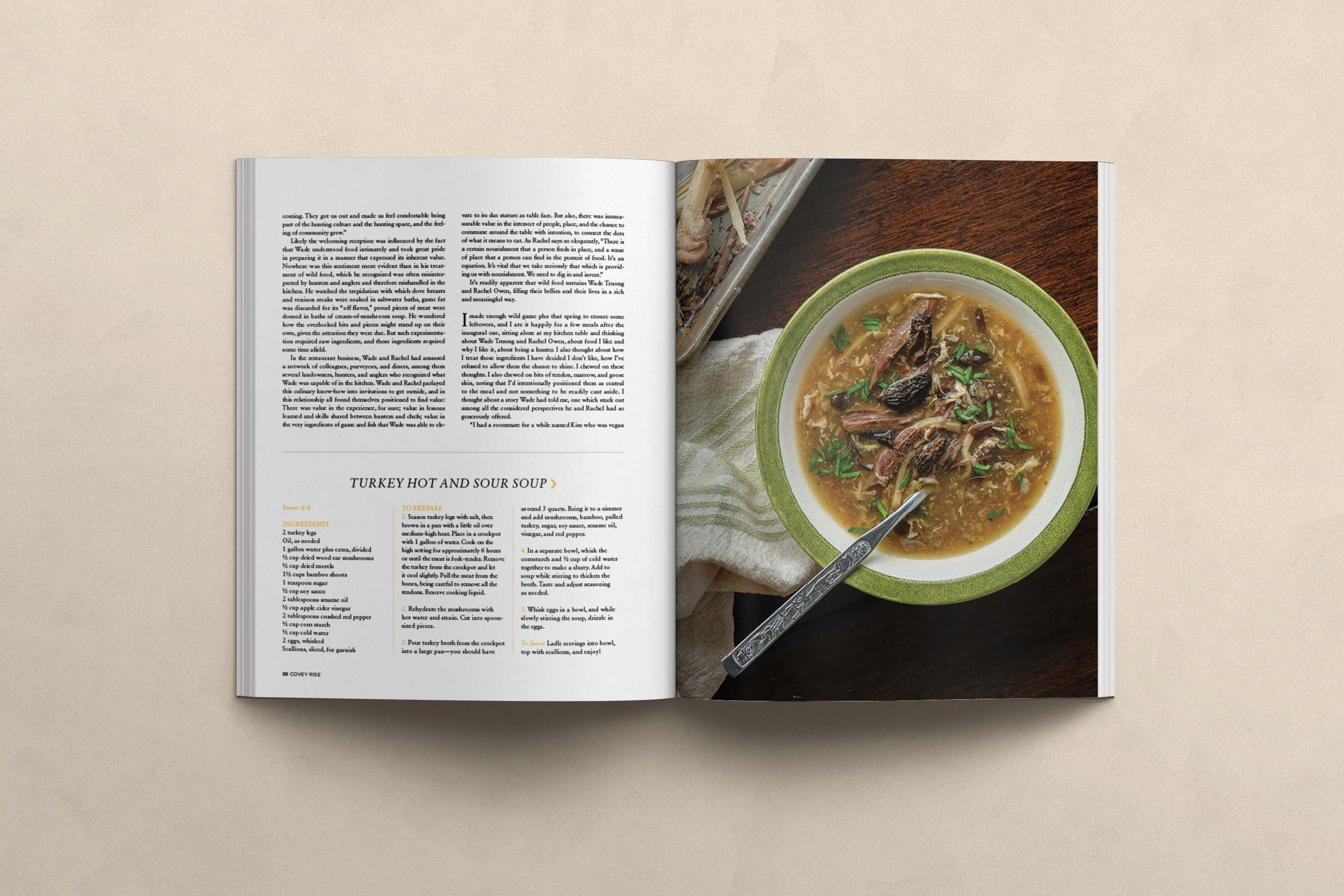

Not long after I met Wade Truong of Elevated Wild, I took an afternoon recon mission in my chest freezer, shoulder deep. I dug clear down to the bottom, exposed the icy shadows where the unidentified, the overlooked, the underwhelming bits of accumulated protein had been laid to rest. There I found some grass-fed Vermont beef joints from a friend’s young steer, some lesser Canada goose breasts that I’d deep-sixed years ago with veiled commitment to re-visit, a mule deer roast whose origin remains a mystery, the package labeled in an unfamiliar hand. I hauled this largess up the stairs and into the kitchen, and I set the packages in the sink to thaw. I looked over these humble beginnings, and for the first time in some time felt truly inspired by food.

In the days that followed I adopted a slow but intentional practice of simmering and reducing, coercing the collagen out of those beef bones and slicing the partially frozen venison tissue-thin. I left the goose meat on the breast bones with the skin intact, added the lot of them to the stock pot, and toasted a handful of cardamom pods in a dry, cast-iron pan. I marveled at the smells that rose from my stovetop, marveled too at the satisfaction with which I cut the tendons from those beef joints, scooped marrow from the bones, and gathered what had theretofore been unbecoming bits of meat into a meal. My countertop became a palette of mixed media, instruments of a work in progress, gristle and offal and bone included, maybe made the heroes. And then, as the spring sun set over the Taconic ridge and the stars became crystalline, I doled out bowls of wild game Pho for my family. Each was a fragrant, silky, chewy, untethered, and slightly complicated gesture to animals I’d known and watched intently, animals that had become chapters in my story, animals I’d somehow previously appreciated only in part and abandoned to the shadows and the freezer burn. In each spoonful there were chill mornings and cupped wings, rice noodles and quickening heartbeats, simple gifts of burnt powder and relived splinters of elation and remorse. The elements came together perfectly, seasoned each bowl with their glory and their flaws.

Wade was right; it was much more than a good soup.

In speaking with Wade Truong and his partner Rachel Owen, in digging into their philosophic recipes collected on the blog Elevated Wild, I’ve been afforded a revelatory education. I’ve been eating for a long time, eating game for a long time, and telling myself for most of that time that I’ve been doing so conscientiously, with integrity and intention. What I failed to recognize, however, and what Wade and Rachel have been showing me and so many others by example, is that my pursuit has been largely academic and therefore incomplete: I have been eating and cooking with an essence of prejudice and a dollop of fear, unwilling to admit that the “gamier” bits, the tougher bits, the bits that require a bit more knife work and a bit more attention, are reminders of something challenging but vital. The reward of food, I’ve come to see, is only in part a full belly and a dopamine response that lingers on the tongue. The true gift is nourishment in its entirety, something that feeds and therefore challenges (excuse the cliché) the mind, the body, and the soul.

*

Wade Truong’s culinary identity was born early, but remains an evolution, another work in progress.

Wade’s parents escaped a war-torn Vietnam alongside sixty or so fellow evacuees by sea, the group huddled in a boat that Wade describes as a craft ill-suited for three people and a bag of decoys. His parents arrived at length in Harrisonburg, Virginia, started a family and a restaurant, and worked to ensure that the Truong children, two boys and two girls, not experience the physical scarcity, the gut-felt hardship, that they’d left behind in Vietnam. Wade’s parents knew what it meant to go a long time without a lot, and in gentle ways they communicated to their children the intrinsic value of enough. This meant that simple gifts like full dinner plates were taken seriously and given consideration, as was the time spent in a meal’s preparation, its utility as a center point around which families gathered. Food was not taken lightly or for granted; it was understood among the Truong children that to leave a plate of food unfinished was ill-advised, and to de-prioritize the weekly family dinner, despite a busy schedule and a family restaurant in which the children worked both front and back of house, was to miss something central about the privilege that is eating.

As Wade grew up and eventually went off to college in Fredericksburg, VA, he leaned on his early restaurant experience as means of making some spending money. In the fine dining scene around Fredericksburg, in restaurants Bistro Bethem and Kybecca, Wade poked and prodded at his understanding of food, and by default also gained a jarring education in the sociological aspects of contemporary western eating. It was at Kybecca that Wade met his partner Rachel Owen, a woman who would continue to both challenge and sustain his maturing perceptions of sourcing and cooking. Considering that time Wade reflects:

“After working in fine dining restaurants in my 20’s I came to the realization that I valued food differently than many folks. I was surrounded by new foods and ingredients all the time, by local farmers and purveyors who took genuine pride in what they sold to me. I was developing a real emotional investment in the process of making food for people, but working in a restaurant kitchen also showed me the other side. I saw what people didn’t like, what they were afraid to try and what they were so willing to throw away. It amazed me how little value food had to some people.”

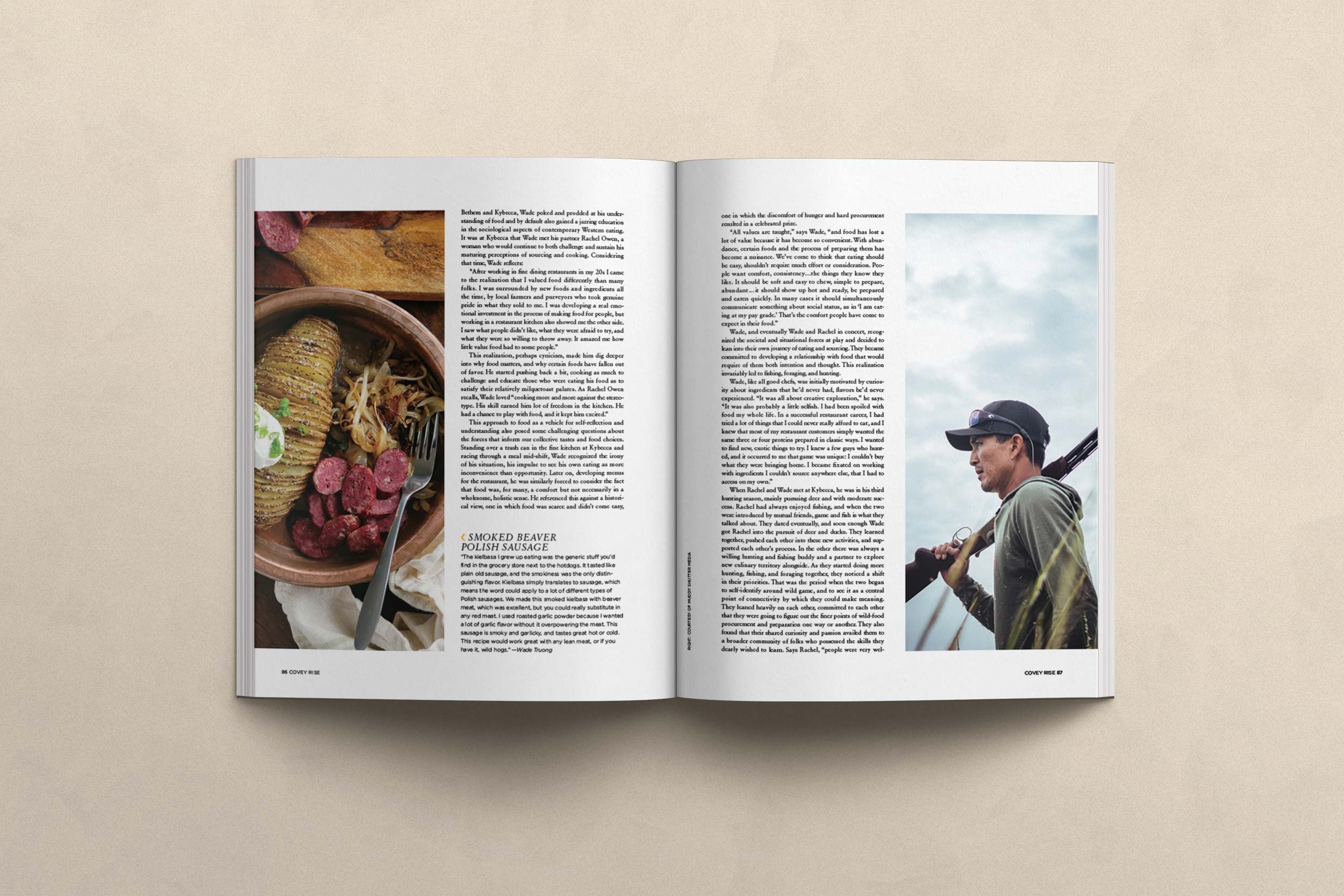

This realization, perhaps cynicism, made him dig deeper into why food matters, and why certain foods have fallen out of favor. He started pushing back a bit, cooking as much to challenge and educate those who were eating his food as to satisfy their relatively milquetoast palettes. As Rachel Owen recalls, Wade loved “cooking more and more against the stereotype. His skill earned him lot of freedom in the kitchen. He had a chance to play with food, and it kept him excited.”

This approach to food as a vehicle for self-reflection and understanding also posed some challenging questions about the forces that inform our collective tastes and food choices. Standing over a trash can in the fine kitchen at Kybecca and racing through a meal mid-shift, Wade recognized the irony of his situation, his impulse to see his own eating as more inconvenience than opportunity. Later on, developing menus for the restaurant, he was similarly forced to consider the fact that food was, for many, a comfort, but not necessarily in a wholesome, holistic sense. He referenced this against a historical view, one in which food was scarce and didn’t come easy, one in which the discomfort of hunger and hard procurement resulted in a celebrated prize. “All values are taught,” says Wade, “and food has lost a lot of value because it has become so convenient. With abundance, certain foods and the process of preparing them has become a nuisance. We’ve come to think that eating should be easy, shouldn’t require much effort or consideration. People want comfort, consistency… the things they know they like. It should be soft and easy to chew, simple to prepare, abundant… it should show up hot and ready, be prepared and eaten quickly. In many cases it should simultaneously communicate something about social status, as in ‘I am eating at my pay grade’. That’s the comfort people have come to expect in their food.”

Wade, and eventually Wade and Rachel in concert, recognized the societal and situational forces at play, and decided to lean into their own journey of eating and sourcing. They became committed to developing a relationship with food that would require of them both intention and thought. This realization invariably led to fishing, foraging, and hunting.

Wade, like all good chefs, was initially motivated by curiosity about ingredients that he’d never had, flavors he’d never experienced. “It was all about creative exploration,” he says. “It was also probably a little selfish. I had been spoiled with food my whole life. In a successful restaurant career, I had tried a lot of things that I could never really afford to eat, and I knew that most of my restaurant customers simply wanted the same three or four proteins prepared in classic ways. I wanted to find new, exotic things to try. I knew a few guys who hunted, and it occurred to me that game was unique: I couldn’t buy what they were bringing home. I became fixated on working with ingredients I couldn’t source anywhere else, that I had to access on my own.”

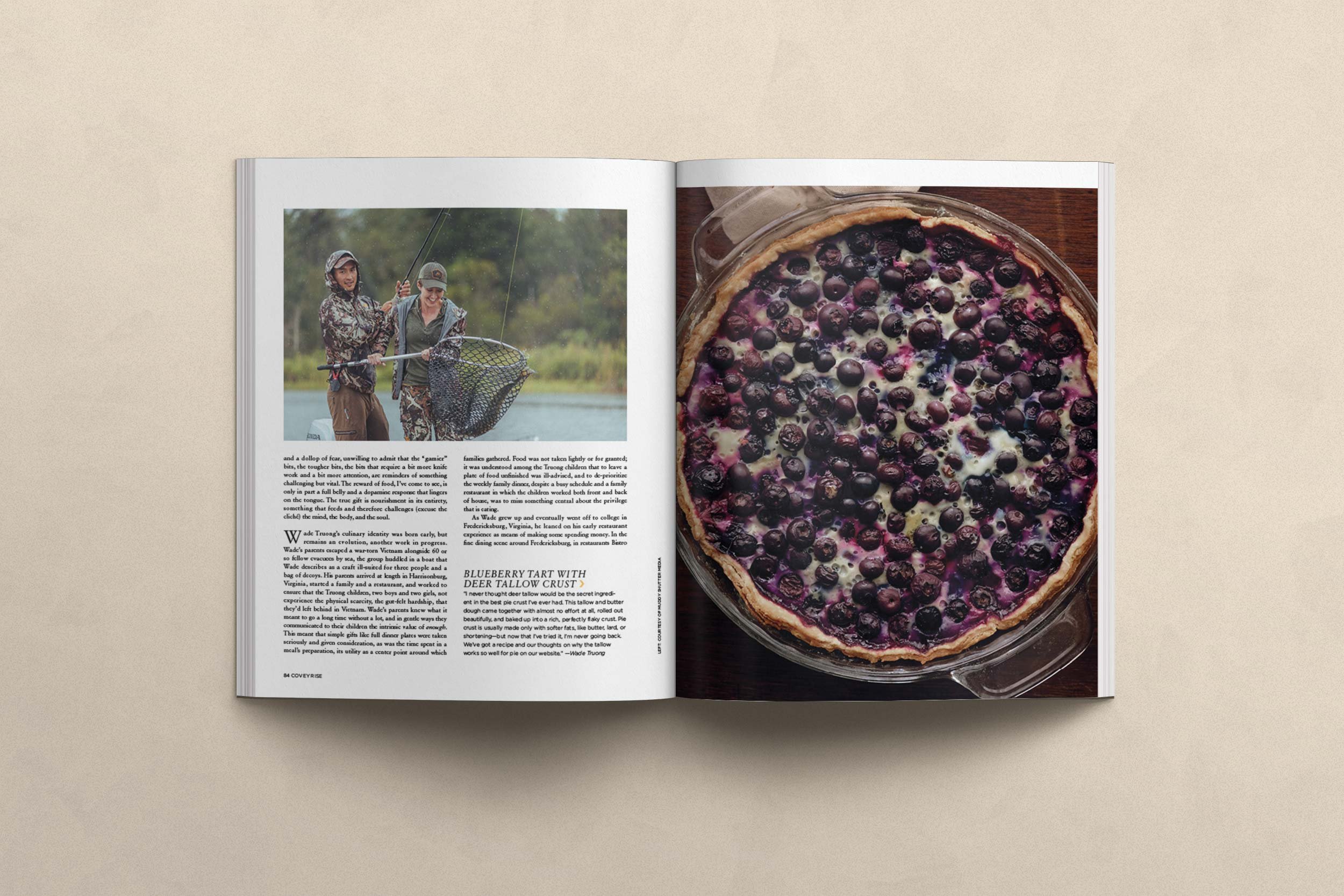

When Rachel and Wade met at Kybecca, he was in his 3rd hunting season, mainly pursuing deer and with moderate success. Rachel had always enjoyed fishing, and when the two were introduced by mutual friends, game and fish is what they talked about. They dated eventually, and soon enough Wade got Rachel into the pursuit of deer and ducks. They learned together, pushed each other into these new activities and supported each other’s process. In the other there was always a willing hunting and fishing buddy, and a partner to explore new culinary territory alongside. As they started doing more hunting, fishing, and foraging together, they noticed a shift in their priorities. That was the period when the two began to self-identify around wild game, and to see it as a central point of connectivity by which they could make meaning. They leaned heavily on each other, committed to each other that they were going to figure out the finer points of wild food procurement and preparation one way or another. They also found that their shared curiosity and passion availed them to a broader community of folks who possessed the skills they dearly wished to learn. Says Rachel, “people were very welcoming. They got us out and made us feel comfortable being part of the hunting culture and the hunting space, and the feeling of community grew.”

Likely the welcoming reception was influenced by the fact that Wade understood food intimately and took great pride in preparing it in a manner that expressed its inherent value. Nowhere was this sentiment more evident than in his treatment of wild food, which he recognized was often misinterpreted by hunters and anglers and therefore mishandled in the kitchen. He watched the trepidation with which dove breasts and venison steaks were soaked in saltwater baths, game fat was discarded for its “off flavor”, proud pieces of meat were doused in baths of cream of mushroom soup. He wondered how the overlooked bits and pieces might stand up on their own, given the attention they were due. But such experimentation required raw ingredients, and those ingredients required some time afield.

In the restaurant business, Wade and Rachel had amassed a network of colleagues, purveyors and diners, among them several landowners, hunters and anglers who recognized what Wade was capable of in the kitchen. Wade and Rachel parlayed this culinary know-how into invitations to get outside, and in this relationship all found themselves positioned to find value: there was value in the experience, for sure, value in lessons learned and skills shared between hunters and chefs, value in the very ingredients of game and fish that Wade was able to elevate to its due stature as table fare. But also, there was immeasurable value in the intersect of people, place, and the chance to commune around the table with intention, to connect the dots of what it means to eat. As Rachel says so eloquently “there is a certain nourishment that a person finds in place, and a sense of place that a person can find in the pursuit of food. It’s an equation. It’s vital that we take seriously that which is providing us with nourishment. We need to dig in and invest.”

It's readily apparent that wild food sustains Wade Truong and Rachel Owen, filling their bellies and their lives in a rich and meaningful way.

*

I made enough wild game Pho that spring to ensure some leftovers, and I ate it happily for a few meals after the inaugural one, sitting alone at my kitchen table and thinking about Wade Truong and Rachel Owen, about food I like and why I like it, about being a hunter. I also thought about how I treat those ingredients I have decided I don’t like, how I’ve refused to allow them the chance to shine. I chewed on these thoughts. I also chewed on bits of tendon, marrow, and goose skin, noting that I’d intentionally positioned them as central to the meal and not something to be readily cast aside. I thought about a story Wade had told me, one which stuck out among all the considered perspectives he and Rachel had so generously offered.

“I had a roommate for a while named Kim who was vegan before she moved in, but who was ok with eating ethically harvested meat. Her boyfriend Cameron was a big hunter and fisherman, and one day they went out and dug clams. I made pasta and clam sauce for dinner, just a really simple meal, and while she was eating, Kim started to cry. She was just so overwhelmed by how good everything was, and how involved she could be in her food. The fact that she had a hand in all of it was almost too much for her. When someone sees that they can be responsible for the honest violence, for the taking and giving, for making things come together so that they can feed themselves, it is powerful. It is not grocery-store transactional: I did x to receive y. It’s bigger than that.”

Wonderfully, the journey into wild food that Rachel and Wade have endeavored has been chronicled on their blog, Elevated Wild. As hunters and eaters of wild game, Wade and Rachel use this platform in part to communicate an awareness of the giant web of conflict that they are not excluded from. They share their stories of the cold dark mornings, the soaking rain and snow, the moments of resounding failure and occasional success in which they find connection. They allow space for the conversations about ecology and much needed conservation, about connecting to the realities of living and dying, the violence that sometimes sustains life. They also showcase the immaculate perfection of the food they cook, food sourced from the most common and simultaneously unique places and ingredients. They share images and recipes for goose neck andouille, air compressor roasted duck, whimsical takes on a variety of cured meats and salumis. Throughout they share, without heaviness or dogma, a belief that a sense of peace comes from finding oneself in a space of adversity, adversity that makes sense as opposed to adversity that is manufactured. Eating, they say, like all things worth doing, should require of us a degree of hardship. Certain bites of food should be a lot to chew, should be hard to get, should be celebrated as rewards after some cold, long, and wet days in the outdoors. In abundance, they say, there is no tension, and in easy food there is little satisfaction. The tension inherent in hunting, fishing, and gathering, the work required and the very real possibility of failure, requires of Wade Truong and Rachel Owen engagement. That is where their meaning is made, and their table filled.

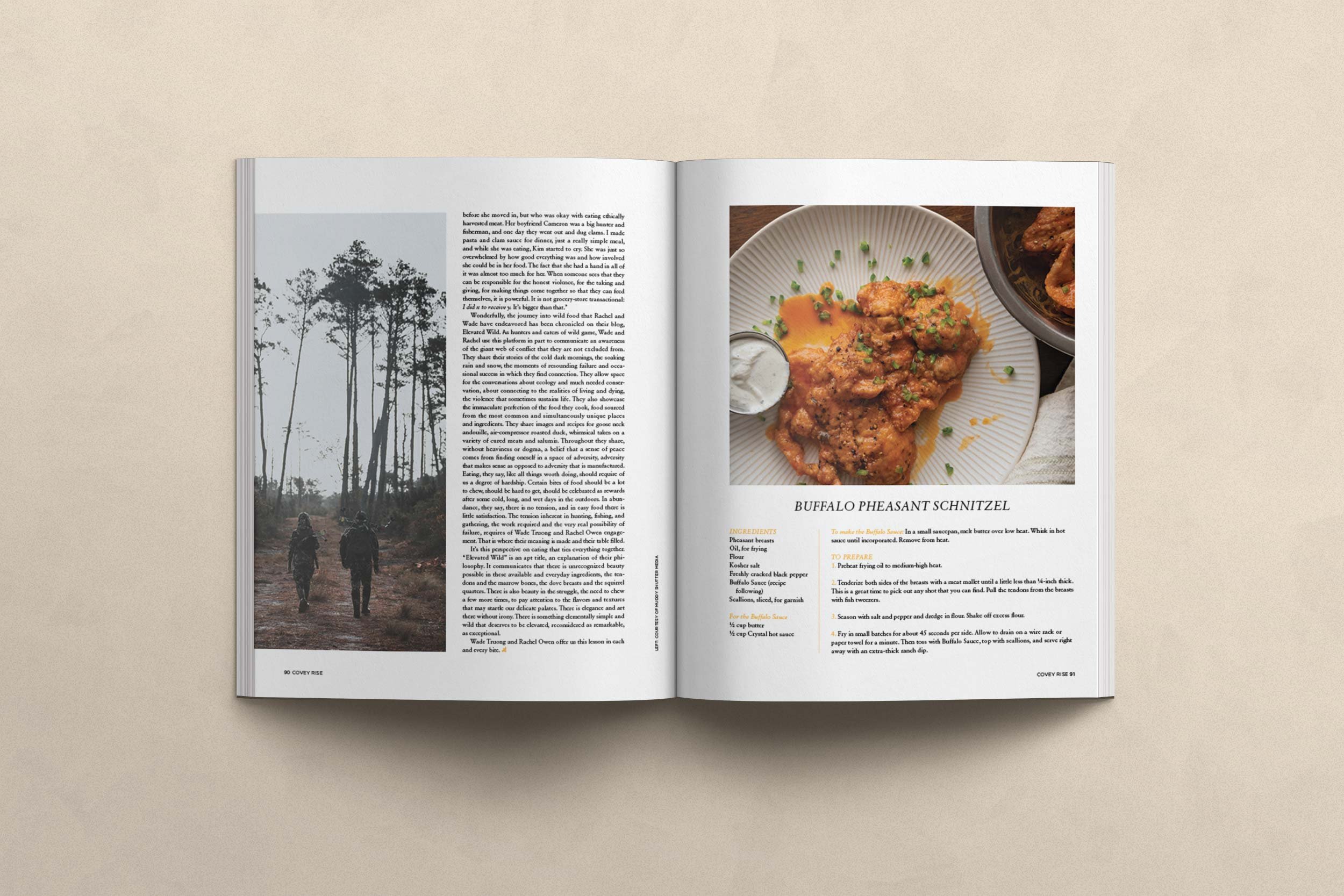

It’s this perspective on eating that ties everything together. “Elevated Wild” is an apt title, an explanation of their philosophy. It communicates that there is unrecognized beauty possible in these available and everyday ingredients, the tendons and the marrow bones, the dove breasts and the squirrel quarters. There is also beauty in the struggle, the need to chew a few more times, to pay attention to the flavors and textures that may startle our delicate palettes. There is elegance and art there without irony. There is something elementally simple and wild that deserves to be elevated, reconsidered as remarkable, as exceptional.

Wade Truong and Rachel Owen offer us this lesson in each and every bite.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine

This issue of Covey Rise can be purchased here.