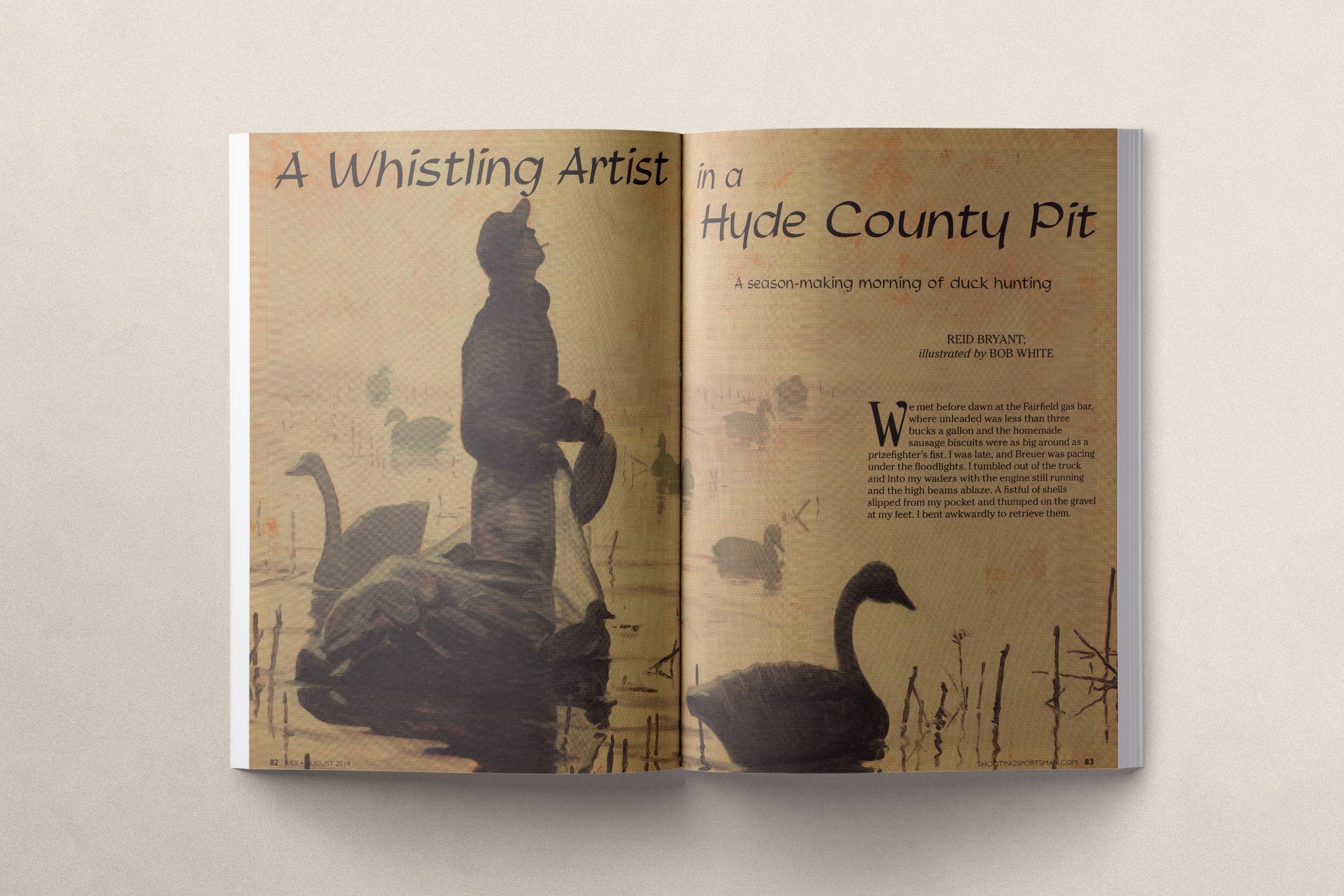

A Whistling Artist

We met before dawn at the Fairfield gas bar, where unleaded was less than three bucks a gallon and the homemade sausage biscuits were as big around as a prizefighter’s fist. I was late, and Breuer was pacing under the floodlights. I tumbled out of the truck and into my waders with the engine still running and the high beams ablaze. A fistful of shells slipped from my pocket and thumped on the gravel at my feet. I bent awkwardly to retrieve them.

The drive down from Norfolk had started not long after 2 AM and had stretched for hours into the eastern Carolina cotton fields. It was a dark and desolate stretch of night that I traced, back roads the whole way, littered with deer, possums and ring-tailed coons hell-bent for my front bumper. I scanned the roadside for eyes and, obliquely aware that the speedometer needle twitched around 70, prayed that no sleepy-town officers would make note of my haste or the red-and-white plates that laid bare my Yankee condolences. So I arrived safe but late and threw my gear into Breuer’s truck, taking a cup and a biscuit from him and burning my tongue when I drank the coffee too soon. But I didn’t care. The wheels were in motion, and the flooded fields were just off the route. A blistered tongue was a small price to pay for whatever lay ahead in the daylight.

We gathered at the field edge, consolidated our gear and ditched Breuer’s truck, pitching our stuff into Raymond Williams’ Chevy. We’d only just met Raymond at the gas bar, but our meeting had not been unforeseen. He’d been described to us as the guide in the know, and he’d come recommended by some of Breuer’s kin—and in the North Carolina lowlands that’s about near enough to make a guy family. Raymond directed his headlights into the corn and lit a cigarette, and through a voice thick with country, he filled in the gaps in his resume. His face glowed in the light of the ember, and I leaned forward from the back seat to listen.

“I work the farm with Joey Ben Williams all spring and summer. He owns the place, and he’s my second cousin, and we been doing this near as long as I can remember. Come fall, when the corn’s all cut, we open the levees and flood the fields and hunt ducks near everyday till the New Year, ’cept Sundays, that is. After the duck season’s done, we get ready to start farmin’ all over again.”

“So you been doing any good the last few days?” Breuer was all brass tacks and, with the nerves he’d built up waiting on me in the dark, the question came out too excited. Raymond just smiled faintly and shrugged.

“Well . . . we been doin’ OK. Didn’t hunt yesterday, what with it bein’ Christmas and all.” That was all we were going to get.

Raymond pulled off of the gravel and cut the engine, and silence descended once more. In the empty space beyond the doors, a chorus of wind and soft, honking hoots ebbed and flowed over the flooded field. “Swans,” Raymond said. “A whole heap a swans.” He cracked his door. “You boys get yer guns. I’ll direct ya to the blind.”

Breuer and I grabbed our gear as a soft rain started to fall. Raymond pointed a flashlight out into it and indicated a hedgerow of corn stubble. It was a swath maybe 10 feet wide of high, dry ground with water on either side, and it ran straightaway out into the black. “You boys follow this dyke out maybe 300 yards and you’ll see the blind. So long as ya don’t get over yer boots in the water, ya can’t miss it. I’m just gonna leave the truck.” Breuer and I nodded and wandered off along the dike, and Raymond drove off to stash his truck in the field-edge cover. We were all alone. The rain came a little bit harder.

Three hundred yards in the dark in a foreign land that you arrived at before dawn can seem like 300 miles. We walked and walked and walked and eventually started wondering aloud if Raymond wasn’t having some fun with us, when all of a sudden a squared grassy hummock loomed in the beam of Breuer’s headlamp. There was a pile of duck decoys on the ground and a few scattered swan decoys showing white, and I looked back where we’d come from to see an orange ember bobbing toward us. We settled into the pit, shucked our guns from their sleeves and loaded up despite the early hour. Raymond arrived with a Lab named Woody and went about setting the blocks. We offered to help, but he shook us off. Out in the flooded corn we could just see him tossing the dekes in a dawn silhouette. Breuer and I whispered excitedly, wondering just what we were in for, and stacked our shell boxes on the bench between us. We’d brought enough steel for six limits—or two greenhorns’ worth of poor shooting, which seemed more likely. Raymond returned and took up his station, looking into a south wind, and illuminated his face by lighting another smoke. Shooting light was a few minutes off, and the swans, still hooting and honking, were beginning to stir in earnest.

Breuer and I had come home for Christmas from lives far north and far west of our Hyde County pit. Breuer had been wandering the globe for years as a fishing guide, working freshwater rivers from one pole to the other and hunting hard in the fringes of fishing seasons. Much to his dismay, I’d settled down early into a schedule more traditional in a part of New England not known for its sporting provenance. That said, in our nearly 20 years of friendship, we’d managed to cross paths at least once a year, usually during duck season and usually in a place not far from the cattails and cornfields. We’d amassed quite a record of frenetic early mornings and a ducks-killed-to-shots-fired ratio so fractional as to be barely a number at all. That said, we’d never set up ourselves properly in duck country, or in a decent pit blind, or in the company of a blue-blooded retriever. And that morning in Hyde County, with shooting light not a minute away, we were soon to find that we’d also not hitched our wagon to a duck-talking fool the likes of Raymond Williams.

The first pass was the easy one, and we weren’t 10 minutes legal when a six-pack of big ducks swung once, cupped and drifted out of the spitting sky bound for our spread. Raymond, perched in the blind door, muttered, “Take ’em,” past his cigarette, and it was a moment of deep country and wingbeats that crashed against dawn’s thunder. Breuer’s old Browning spit and jumped, spit and jumped again, and in the concussion I got a couple off too. In the going away, Raymond lifted his gun to bat cleanup, but he thought better of it when Woody charged out. Cutting the shallow water, Woody returned with one bull pintail, then another. The ducks were dressed gaudily in their zoot-suit plumage, with the long hatband feathers standing sharp from their aft ends. Breuer was ebullient; I was more reverent. We looked at the birds and congratulated ourselves and each other a few times, and I smoothed the feathers of mud and water.

Breuer was wiggling in his excitement near as much as Woody, and I was lost in the reverie, when Raymond hissed, “Settle down in!” We hitched back under the lip of the blind, and Raymond worked his pintail whistle past his cigarette, rolling his eyes skyward to follow the circling pack. For our part, we simply stayed still, followed his eyes and kept clear of the rising wind and rain. Raymond dribbled some quacks in among the whistles and chirrs, just enough to keep the ducks interested, and they swung and swung without giving up altitude. From 60 yards below we could see the spear points of the tailfeathers set against the sky, but that was the extent of it. Maybe Breuer wiggled too much, or the wind pushed the birds too hard, or our eager faces shone too bright against the ground. Whatever it was, the ducks shoved south and let a tailwind send them skimming off toward the safe haven of Lake Mattamuskeet.

“Damn pintails,” Raymond muttered. And so the morning went.

Raymond let on early that, us being new to his blind and him taking pride in such things, he was set on us scoring a limit. The rain and wind came in waves out of the north, and in the momentary lulls the ducks rose and circled and buzzed our blind regularly enough. And Raymond worked all the while, scanning the sky, smiling at all of Breuer’s jokes, wondering just enough about our respective lives to show that his wonder was genuine. He’d pull on his cigarette and play a small symphony on his whistle and Wench [??], and clean up our mistakes when we needed him to. He pulled a wigeon out of a pack that was scraping the sky, long after Breuer and I had emptied our guns and not loosed a feather. He dropped the bird stone dead and smiled just enough to show he knew how good he was, as if the string of leg bands around his neck hadn’t proven it already. He folded a drake pintail that I missed twice and didn’t let on a bit about it until Breuer asked too loud of me, “Hey, did you get that bird?’

I could have gotten away with it, but I said, “No . . . I think Raymond must have.”

To which Breuer redirected the question, “Hey, Ray, did you get that bird?”

Raymond, the consummate professional, just kept his eyes skyward and said in a soft voice, “Well, it was the one I was aimin’ at . . . .”

When the teal started coming, our limits grew short, and we didn’t mind closing them that way. The green-wings bounced in volleys in and around and over the blind, and we poked away at them, and Woody gathered them up. We stacked them beside the big ducks, and I marveled at their size: the biggest teal I’d ever seen, even at the end of the migration. They clearly had been bingeing on Raymond’s and Joey Ben’s corn, and I knew they’d eat as well as ducks could despite their small size. Breuer, ever the optimist, had laid in charcoal and bourbon for the dinner hour, and we looked at our limits fast filling and made plans for a spicy-sweet rub on duck skin grilled crisp. Nearing noon, with the swans still moving all about us, a lone duck swung too low, and Breuer dumped it clean. Woody liberated himself again from the pit.

Raymond smiled. “Merganser,” he said, and I thumped Breuer on the arm.

But Breuer didn’t care. “Don’t worry,” he said, “we’ll feed it to my idiot brother-in-law. Guarantee he won’t know the difference . . . .” And the saddest part is, he didn’t!

We helped Raymond gather the dekes in the rain, and we left them at the blind for the day to come. Back at the truck we shook hands with Raymond and with Joey Ben, who’d come out to see our take. It was something to admire, we all agreed: a mixed bag of teal, pintails, wigeon and shovelers, with a merganser thrown in for a laugh. They’d been taken clean from the Hyde County skies, and we’d lost not one, thanks to Woody. They had eaten well on corn, and they would eat well on our family table, with bourbon to baste and to toast with—a fine way to celebrate a year fast closing. We lingered there for a minute, exchanging pleasantries, letting the rain splatter our hat brims and windshields. And as we turned to leave, I watched Raymond Williams light another cigarette, pull onto the gravel road and off toward his home outside of Fairfield.

What for me was a season-making morning of friendship and fine shooting was just another day at the office for old Raymond. But I could tell from the way he fluttered those calls, and pulled down those ducks, and settled his dog when they circled that it was a job he didn’t mind doing. Out there in the Carolina corn he was plying his craft and shaping it delicately into art. And on our way out of town, Breuer and I vowed to meet Raymond again one year out in the mud of a Hyde County morning.

First Published in Shooting Sportsman Magazine